Introduction

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a common adverse

drug reaction, with an estimated worldwide incidence of 14–19 cases

per 100,000 people, 30% of which are associated with jaundice

(1). A 2019 retrospective study

involving 308 medical centers in the major cities of mainland China

noted that the incidence of DILI was 23.80 per 100,000 individuals,

which was higher than that in Western countries. It also reported

that DILI cases were rising every year, and that traditional

Chinese medicines and antituberculosis medicines, among others,

were the main drug classes that caused DILI (2). Notably, the incidence of DILI is

higher in hospitalized populations (3). DILI refers to an injury to the liver

or biliary system caused by the ingestion of hepatotoxic drugs.

Mechanistically, DILI can be attributed to either endogenous

toxicity (dose-related) or specific toxicity (dose-independent) and

indirect injury, a recently proposed type that refers to injury to

the liver or biliary system caused by a drug that alters a

patient's original liver disease or immune status (4). Endogenous toxicity is predictable and

can occur hours or days after an individual is exposed to a drug.

By contrast, specific toxicity is often unpredictable and is

determined by the interaction of environmental and host factors

with the drug (5). Sex is a

significant risk factor for DILI; young women are at a higher risk

of drug overdose events, which may be due to differences in

psychosocial factors, physiological differences and behavioral

patterns (6,7). According to the results of the Third

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the United

States, it was found that women take acetaminophen (APAP) more

often than men (8). In addition,

it has been shown that the clearance of APAP from men's bodies is

22% higher than that from women's bodies, because men have higher

glucuronidation activity, which is a key enzyme in APAP metabolism

(9).

The primary cause of endogenous DILI is considered

to be the supratherapeutic use of APAP, which is one of the most

widely used and popular over-the-counter analgesic and antipyretic

medications across the world (10). APAP is included in the World Health

Organization's list of essential medicines recommended as a

first-line treatment for the majority of pain and fever cases, and

is considered safe at therapeutic doses; however, when overdosed,

it can cause life-threatening hepatotoxicity (11). The United States has the highest

proportion of DILI cases caused by APAP (~30% of cases), followed

by Pakistan (~16% of cases) (12).

The first reports of APAP poisoning in humans appeared in the 1960s

when Davidson and Eastham (13)

reported two patients who developed hepatotoxicity after overdose;

both patients succumbed on day 3 after overdosing, and in both

cases, the pathologic features of the liver sections were

suggestive of marked acute lobulocentric fulminant hepatic necrosis

(14). Notably, toxic effects are

highly likely with APAP at a dose of 150 mg/kg (15); this dose has remained virtually

unchanged over the past 20 years although N-acetylcysteine

(NAC) has been introduced as a clinical antidote to APAP poisoning.

Therefore, understanding the pathogenesis and risk factors of

APAP-induced liver injury (AILI), and proposing more effective

means of prevention and treatment are imperative.

Clinical manifestations and biomarkers

APAP toxicity is a time-dependent event, with the

liver being the first organ to come into contact with absorbed

APAP. This toxicity can occur from administration errors,

accidental ingestion and intentional self-administered overdose

(16). APAP hepatotoxicity can

generally be divided into four stages of presentation, with the

first stage characterized by nausea, vomiting, right upper

abdominal pain and other nonspecific symptoms that begin within

minutes to hours of ingestion. Some patients may initially be

asymptomatic, with hepatic function markers, such as serum

aspartate transferase (AST), prothrombin time (PT) and serum total

bilirubin (TBIL), at baseline levels (17). During the second stage,

abnormalities in liver function, such as an increase in AST

activity, PT and TBIL levels, occur and the patient may present

with nausea, pain in the right upper abdomen and jaundice (18). The third stage is often the peak of

hepatic injury, with marked necrosis of hepatocytes. AST levels can

peak at this stage, but some patients do not show typical symptoms.

In patients with more severe liver injury, fulminant liver failure,

including hepatic encephalopathy and hyperbilirubinemia, can occur

(19). The fourth stage is often

the recovery stage, when the indicators of various liver functions

may return to the baseline. Nevertheless, a small number of

patients experience liver and other organ failure, which is

life-threatening. Various factors can increase the risk for APAP

toxicity, which is mainly mediated by the metabolic pathway of APAP

(12). Plasma biomarkers detected

through liquid biopsies are currently considered the gold standard

for understanding the mechanisms of in vivo injury in

patients (20). Protein adducts in

plasma can serve as specific biomarkers of APAP toxicity. High

levels of APAP protein adducts (APAP-AD) in serum samples from

patients with acute liver failure (ALF) induced by APAP overdose

and lower levels of adducts in other types of liver injury, such as

pyrrole protein adducts, can be detected by high-sensitivity

high-pressure liquid chromatography combined with electrochemical

detection (21). A major advantage

of measuring these protein adducts is that their half-life in serum

is considerably long; therefore, they can be used to accurately

diagnose AILI long after APAP ingestion (22).

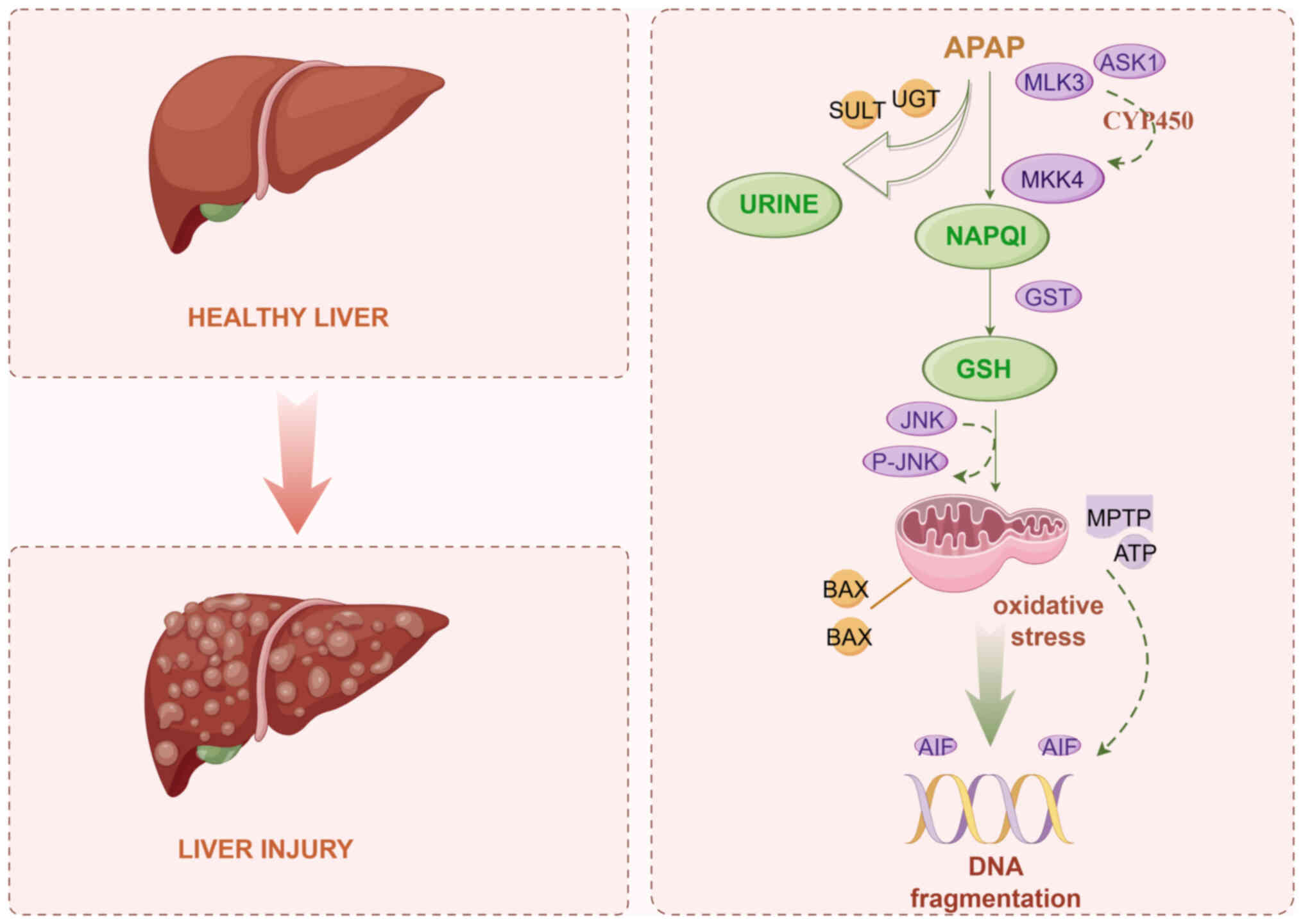

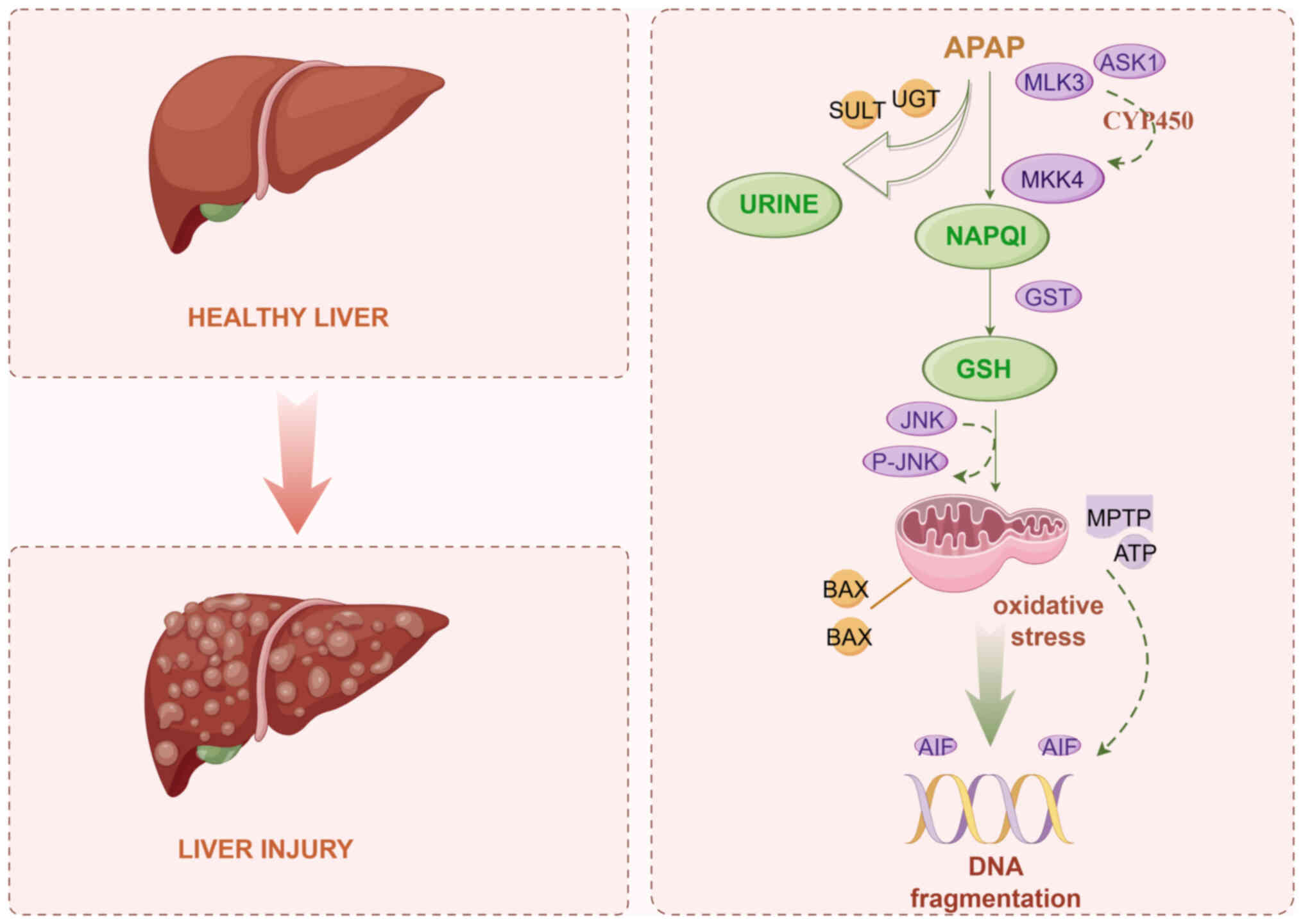

Pathophysiological mechanisms of AILI

Continuous improvements in research equipment and

methods in the fields of modern medicine and microbiology have

enabled a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying AILI.

Production of toxic metabolites, generation of protein adducts

leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and peroxynitrite formation,

and cell death due to DNA strand breaks are believed to be the

primary mechanisms of APAP-induced hepatotoxicity (Fig. 1). Recent studies have reported the

close involvement of several events in the onset of APAP toxicity,

which have been described in the following sub-sections.

| Figure 1.Underlying mechanism of APAP-induced

liver injury. APAP, acetaminophen; UGT, glucuronosyltransferase;

SULT, sulfonyl transferase; ASK1, apoptosis signal-regulating

kinase 1; MLK3, mixed lineage kinase 3; MKK4, mitogen-activated

protein kinase kinase 4; NAPQI,

N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine; GST, glutathione

transferase; GSH, glutathione; MPTP, mitochondrial membrane

permeability transition pore; AIF, apoptosis-inducing factor. |

Toxic metabolites

The liver is a major target for drug toxicity

because it serves a crucial role in the metabolism of drugs, toxins

and other exogenous substances, and their removal from circulation.

The liver is not only responsible for the biotransformation of

drugs into more easily excretable forms, but it also protects the

body from the potentially harmful effects of drugs through its

detoxification system. Approximately 90% of APAP taken at

therapeutic doses is metabolized by phase II-coupled enzymes,

mainly glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) and sulfonyl transferases

(SULTs), which convert it into non-toxic compounds that are then

excreted in the urine via the biliary tract and renal system

(23). A small portion (~5%) is

excreted in the urine without biotransformation, whereas the

remaining portion (~5%) is bio-transformed by the cytochrome P450

(CYP450) system, specifically via CYP2E1 and CYP1A2 metabolism, to

produce the reactive intermediate molecule

N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), which can be

readily detoxified to the water-soluble and innocuous mercapturic

acid by glutathione (GSH) (24).

Microsomal GSH transferase (GST) catalyzes the binding of NAPQI to

GSH, thus reducing its toxicity. Notably, the formation of NAPQI,

the active metabolite of APAP, is an important step in the

development of hepatotoxicity (25). Exceeding the therapeutic dose of

APAP leads to saturation of the phase II-coupled enzymes;

therefore, excess APAP is diverted to another metabolic pathway,

the CYP450 system, which results in the production of a large

amount of NAPQI in hepatocytes (26). This leads to GSH overconsumption,

which lowers GSH levels. Excess NAPQI binds to cellular

biomolecules, such as proteins, nucleic acids and lipids, a process

that occurs predominantly in the centrocytes and hepatocytes of

hepatic lobules. The degree of binding and the relative amount of

covalent binding have been reported to be associated with the

development of toxicity; the formation of protein adducts causes

oxidative stress and dysfunction, which further leads to hepatocyte

necrosis (27). Notably,

therapeutic doses of APAP do not cause liver injury if UGT and

SULTs are active and the hepatic GSH stores are adequately

maintained, because all of the NAPQI produced is efficiently

removed.

Oxidative stress in mitochondria

Mitochondria are vital organelles for cellular

energy production, which also have an important role in cell

signaling. Toxic doses of APAP can alter mitochondrial morphology

and function. Owing to the reactive nature of NAPQI, one of the

early events following its formation and the depletion of hepatic

GSH stores is the generation of NAPQI adducts on cellular proteins

(28). Mitochondria are a key

early target for NAPQI adduct formation. The levels of such adducts

markedly increase in mitochondria after APAP overdose into mice,

accounting for ~65% of the whole cytoplasm; mitochondrial protein

adducts, such as mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase, α-subunit of

ATP synthetase and GSH peroxidase (GPX), have been found in mice

(29). Large amounts of NAPQI can

cause GSH depletion, which leads to increased release of

H2O2 in mitochondria, which is an important

oxidative stress signaling molecule that initiates the

auto-activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1),

further triggering the activation of mitogen-activated protein

kinase kinase 4. Ultimately, this leads to the cytoplasmic

activation of the MAPK, JNK, which belongs to a subgroup of MAPKs

that are mainly activated by cytokines and environmental stress

(30). JNK activation and

attenuation of liver injury have been observed in ASK1-deficient

mice, thus demonstrating that ASK1 is upstream of JNK; notably,

this activation is more pronounced at a late stage (i.e., ≥3 h

after APAP administration), with little effect at an earlier time

point (1.5 h) (31).

Another possible mechanism of JNK activation that

has recently been proposed is that it can be released from GSTπ

(32), an important detoxifying

enzyme that is a member of the GST family that binds to JNK.

Oxidative stress or direct binding of NAPQI can trigger the release

of JNK from GSTπ. Phosphorylated JNK can bind to the mitochondrial

outer membrane scaffolding protein and inhibit mitochondrial

electron transport through an Src-mediated process. Protein adducts

in mitochondria trigger initial electron leakage at the level of

complex III of the electron transport chain, causing the formation

of superoxide radicals outside the inner mitochondrial membrane

(IMM), which in turn triggers mild oxidative stress in the

cytoplasm (33). In addition,

activated JNK translocates from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria,

increasing the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP)

activity, which then elevates mitochondrial oxidative stress; this

strongly amplifies mitochondrial superoxide radical formation,

which can induce mitochondrial dysfunction and lead to

hepatocellular necrosis. NAPQI-induced formation of mitochondrial

adducts and the ensuing mitochondrial oxidative stress have been

well-studied in recent decades (34,35),

but the amplification of JNK is a more recent discovery (36).

Peroxynitrite formation

Although mitochondria exhibit strong antioxidant

defense activity, they can experience oxidative stress after

ectopic JNK expression, mainly due to the active disruption of

electron transfer by JNK-mediated signaling (37). Mitochondrial stress-generated

superoxide radicals can react rapidly with nitric oxide to form a

potent oxidant, peroxynitrite, which is a highly reactive and

nitrifying compound that causes APAP toxicity (38). During APAP hepatotoxicity,

peroxynitrite is mainly produced in hepatocytes and liver

sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs); the formation of

nitrotyrosine protein adducts, which are mainly found in

mitochondria, indirectly proves that peroxynitrite is formed in the

mitochondria of hepatocytes (39).

Time course studies of peroxynitrite formation have confirmed its

occurrence only in mitochondria after JNK translocation (40). This amplified oxidative and

nitrosative stress in the mitochondria, accompanied by inhibition

of the antioxidant system and nitrification of mitochondrial

components, can induce changes in mitochondrial membrane potential

and morphology, such as the opening of the MPTP, which leads to a

shift in MPT. This alteration, although reversible in the early

stages, eventually leads to an irreversible collapse of the IMM

potential and cessation of ATP synthesis. MPT induction may be

dependent on the magnitude of the upstream signal from APAP; mice

have been shown to exhibit transient MPT induction when the APAP

dose is low and irreversible induction at higher doses (41). The result is matrix swelling and

outer mitochondrial membrane rupture, which releases intermembrane

proteins such as endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF)

into the cytoplasm; these proteins can later translocate into the

nucleus, leading to mitochondrial DNA breaks, as well as massive

mitochondrial dysfunction and swelling along with DNA damage, which

trigger programmed cellular necrosis (42). This event can directly cause the

cessation of ATP synthesis.

In addition to the unregulated release of

intermembrane proteins via the MPTP, they can be prematurely

released through the Bax pore. Bax, a member of the Bcl-2 family of

proteins, is located mainly in the cytoplasm; upon stimulation, it

can translocate to the outer mitochondrial membrane, form a pore,

and trigger the release of intermembrane proteins (43). In addition, JNK and phosphorylated

JNK are recruited to the mitochondria via the SH3

homology-associated BTK-binding protein, a mitochondrial outer

membrane protein that can further enhance mitochondrial damage and

necrosis (44). GSH supplements

not only provide excess cysteine as an energy substrate but also

serve an important role in scavenging free radicals and

peroxynitrite (45). Selective

clearance of mitochondrial peroxynitrite increases upon accelerated

restoration of mitochondrial GSH levels, further demonstrating the

critical role of peroxynitrite in pathophysiology (46).

Microcirculatory dysfunction

The hepatic microcirculatory milieu, which consists

mainly of LSECs, hepatic stellate cells and hepatic macrophages,

serves an important role in maintaining intrahepatic homeostasis

and hepatocyte function, regulating vascular tone and controlling

inflammation (47). Although

hepatocytes are the primary target of the cytotoxic effects of APAP

overdose, morphological alterations in LSECs are also associated

with APAP-induced liver disease. Drugs are transported through

blood sinusoids by various mechanisms, including organic anion and

cation transport proteins of the basolateral membrane, other

transport proteins such as Na+-taurine bile acid

co-transporting polypeptides or prostaglandin transport proteins,

and passive diffusion, before metabolism and clearance within

hepatocytes (48). APAP-induced

LSEC injury precedes liver injury; thus, LSEC injury is considered

an early event in liver injury (49). Intra-endothelial perturbations,

including swelling of LSECs, gap formation and estradiol

incorporation, occur as early as 2 h after APAP overdose,

suggesting that LSECs can metabolize APAP (49). In a previous study, gavage

administration of APAP to male C57Bl/6 mice revealed that a large

number of SECs swelled at 0.5 and 1 h, whereas the hepatocyte

morphology remained intact, and serum AST and alanine

amiotransferase (ALT) levels, which are indicators of hepatocyte

injury, were not significantly increased. These results suggested

that LSECs are damaged before hepatocytes (50). Furthermore, scanning electron

microscopy after APAP intoxication has revealed the induction of

large pores in LSECs, accompanied by the accumulation of

erythrocytes, enlargement of the Disse space and collapse of

sinusoidal lumen in a mouse model (51). Massive centrilobular congestion is

an important feature of APAP-induced hepatotoxicity in mice, which

occurs before the appearance of necrosis, and is induced by

hepatocytes and their relationship with LSECs. Vascular congestion,

interstitial congestion and sinusoidal collapse may impair hepatic

circulation, thereby exacerbating toxicity by causing additional

hypoxic injury (52). Furthermore,

serum hyaluronic acid (HA) levels have been shown to be elevated in

patients with APAP-induced acute hepatic injury (53); HA is mainly produced by mesenchymal

cells and is found at low levels in normal human plasma, as it is

rapidly cleared by LSECs. Notably, clearance of HA is impaired when

LSECs dysfunction, which may be related to the HA receptor and DNA

breaks on defective LSECs (54).

Hence, HA levels may be used to determine the extent of sinusoidal

vascular endothelial cell damage (55). Formaldehyde-treated serum albumin

(FSA) is a commonly used model ligand for the LSEC scavenger

receptor that has been widely used to study the scavenger receptor

function of LSECs, particularly when assessing the ability of LSECs

to scavenge blood-borne waste macromolecules. FSA expression in the

hemorrhagic centrilobular region has been reported to diminish 2 h

after APAP gavage in a mouse model, suggesting impaired LSEC

scavenger receptor function or a reduced number of cell surface

receptors (50).

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress

The ER serves a crucial role in a number of cellular

processes, including protein folding, assembly, transport,

post-regulation, secretion and quality control of membrane

proteins, lipid synthesis and regulation of intracellular calcium

homeostasis. Disturbance of ER function by stimuli such as altered

cellular redox status, oxidative stress, calcium homeostasis

imbalance, hypoxia or energy deprivation can lead to the

accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER, leading to ER stress

(56). The ER can respond to

stress through a complex series of events known as the unfolded

protein response (UPR). The UPR comprises a series of signaling

events, such as the activation of ER transmembrane proteins,

including activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), which induces

various transcription factors such as pro-apoptotic proteins (e.g.,

CHOP) (57).

In contrast to other mechanisms of toxicity, such as

mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, ER stress has not

been comprehensively evaluated in the context of drug-induced side

effects. Some data from mouse experiments have suggested that ER

stress is a relatively late event in APAP toxicity, with

significant stress occurring only 12 h after APAP administration

(58). By contrast, hepatic

mitochondrial alterations, JNK activation and oxidative stress

occur much earlier in mice after the same dose of APAP (59). Sublethal doses of APAP can result

in a redox shift in ER compartments; notably, a shift of ER

oxidoreductase from the redox state to the oxidized state in

hepatic microsomes suggests that the ER is in a state of redox

imbalance. This state impairs ER oxidoreductase function and may

initiate ER-associated signaling pathways, including ATF6 and CHOP

activation, which inhibits the expression of anti-apoptotic genes

and activates pro-apoptotic genes (60). By contrast, CHOP deletion has been

reported to protect mice from liver injury after APAP poisoning

(61). Moreover, caspase-12, an

ER-resident caspase, is transiently activated by ER stress-related

factors such as calcium ion imbalance, misfolded protein

accumulation, and induction of ER stress inducers. It can be

considered that the activated state of caspase-12 does not last

long, but occurs for a short time and then disappears. By contrast,

the mode of cell death in APAP hepatotoxicity is

caspase-independent apoptosis, triggered instead by activation of

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (62). The mode of cell death in APAP

hepatotoxicity is thought to be necrosis rather than apoptosis

because there is no caspase activation following APAP overdose,

despite mitochondrial rupture and release of intermembrane

proteins. Moreover, caspase inhibitors are ineffective in

protecting the liver from APAP toxicity (63).

NAPQI can covalently bind to a variety of microsomal

proteins, such as GST, protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and

calreticulin. Since PDI and calreticulin have major roles in

protein folding and calcium chelation within the ER, covalent

binding of NAPQI to these proteins can induce ER stress (64). Furthermore, ER stress may be a

secondary consequence of mitochondrial dysfunction. The ER and

mitochondria are closely linked, and the physical binding of these

two organelles creates a structure called the

mitochondria-associated ER membrane; in a physiological context,

this connection allows for continuous calcium transfer. During ER

stress, calcium can be transferred to the mitochondria in large

amounts through these microstructural domains or as a result of

increased cytoplasmic calcium levels; thus, the induction of ER

stress can increase mitochondrial calcium overload, which in turn

favors mitochondrial membrane permeability and the release of

pro-apoptotic factors, such as cytochrome c and AIF

(65). Notably, ER stress can also

stimulate the expression of the mitochondrial stress factor heat

shock protein 60 (HSP60) in mouse hepatocytes, and may impair

mitochondrial respiration and decrease mitochondrial membrane

potential. This finding not only reveals the complex interaction

between the ER and mitochondria, but also demonstrates that ER

stress can induce mitochondrial stress (66).

Aseptic inflammation

Inflammatory liver diseases that are not caused by

pathogens, such as AILI, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and

alcoholic liver disease, are considered ‘sterile’ (67). While hepatocellular necrosis is the

initial underlying mechanism of APAP-induced hepatotoxicity, the

second step in liver injury is a sterile inflammatory response to

necrotic hepatocytes. The total number of leukocytes in the livers

of mice has been shown to increase ~3-fold a total of 18 h after

APAP injection, suggesting a notable inflammatory response during

AILI (68). Hepatocytes release

intracellular components that can act as damage-associated

molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as high mobility group box 1

protein, DNA fragments and HSPs, which act as ligands for Toll-like

receptors on macrophages (69),

thus leading to transcriptional activation of cytokines and

chemokines. Most of these inflammatory factors can be released

directly into circulation, but a few cytokines require caspase-1

activation to trigger their activity. Activated caspase-1 induces

the production of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex, which comprises

NLRP3, caspase-activated deoxyribonuclease and procaspase-1

(70); this complex mediates a

pro-inflammatory response through neutrophil and monocyte

activation, and recruitment to the liver (71). When neutrophils are activated

following an APAP overdose, those in the peripheral circulation

tend to move toward the site of injury in the early stages, with

the majority migrating to areas of necrosis, after which the injury

begins to worsen, peaking at 24 h. Subsequently, the neutrophil

levels begin to decrease during the recovery phase of liver injury.

Monocytes participate in inflammation via phagocytosis, regulates

connective tissue remodeling and fibrosis processes and the

formation of extracellular traps (72). Monocytes also serve an important

role during the aseptic response. On the one hand, activated

monocytes can control neutrophil activation and recruitment through

chemokines; on the other hand, when monocytes reach the necrotic

area, they can be transformed into monocyte-derived macrophages,

which leads to a rapid increase in the number of hepatic

macrophages. CCL2 is a mediator of monocyte entry from bone marrow

into circulation (73). Although

the aseptic response removes necrotic cell debris and promotes

tissue repair, leukocytes contribute to tissue damage. Given the

dual role of inflammation in APAP hepatotoxicity, it could be

hypothesized that a moderate inflammatory response might contribute

to tissue repair and hepatocyte regeneration, whereas an excessive

response could exacerbate liver injury (74).

Treatments

The primary treatment for APAP poisoning is the use

of the specific detoxifying drug NAC, which can minimize APAP

damage to the liver. In addition, liver transplantation is an

option to consider for patients with ALF. However, NAC may cause

some adverse effects in clinical application and there is a problem

of drug resistance. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop

new drugs to improve the therapeutic efficacy. The present study

explores the possible therapeutic targets for APAP poisoning and

reviews the current major therapeutic approaches to inform future

treatment strategies.

Inhibition of toxic metabolite

production

Historical progress of research on NAC is shown in

Table I. The first demonstration

of the detoxifying role of GSH in DILI was made by Mitchell et

al (75) at the National

Institutes of Health in 1973, and their first report on oral NAC

treatment for APAP overdose was published in May 1977. In 1985, NAC

treatment was found to be effective in detoxifying NAPQI in mice 1

h after APAP administration (76),

and it was suggested that this detoxification may be related to

enhancement in APAP-GSH metabolite formation and attenuation in

protein adduct synthesis. Notably, NAC is a precursor of GSH; NAC

is deacetylated to cysteine and conjugated to glutamate, which is

further converted to glutamylcysteine by glutamate-cysteine ligase

(GCL) in hepatocytes. Glutamylcysteine binds to glycine via GSH

synthetase to produce GSH, which effectively prevents

hepatotoxicity due to GSH depletion (77). NAC also reduces the covalent

bonding of APAP, thereby attenuating hepatic necrosis, and improves

mitochondrial energy metabolism through ATP maintenance in addition

to scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) and peroxynitrite

(78). This energy generation is

accomplished primarily through the Krebs cycle, also known as the

tricarboxylic acid cycle or aerobic respiration, which is part of

the cellular respiration process. The Krebs cycle maintains cell

survival and function by breaking down glucose into carbon dioxide

and water to produce energy (ATP) (77). Furthermore, NAC exhibits

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties (79). Approximately 40 years after its

introduction, NAC remains the only Food and Drug

Administration-approved antidote for APAP overdose. The standard

oral or intravenous dosing regimen of NAC is highly effective in

patients who develop a moderate overdose within 8 h of APAP

ingestion (80). NAC was initially

administered orally; however, intravenous infusion is currently

more common in clinical practice. Mainly due to the fact that the

patient is in a coma and cannot be administered orally, at the same

time, intravenous injection can ensure 100% of the drug enters the

blood circulation, avoiding uncertainty in the oral absorption

process.

| Table I.Historical progression of NAC for the

treatment of APAP hepatotoxicity. |

Table I.

Historical progression of NAC for the

treatment of APAP hepatotoxicity.

| First author,

year | Research

progress | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Peterson, 1977 | The first report of

NAC treatment of APAP overdose was presented. | (120) |

| Akakpo, 1985 | Oral NAC was

approved by the FDA for APAP overdose. | (33) |

| Corcoran, 1985 | After 1 h of APAP

treatment, NAC effectively promoted detoxification of NAPQI in

mice, leading to attenuated protein adduct formation. | (121) |

| Smilkstein,

1988 | Administration of

NAC within the first 8–10 h after APAP ingestion was revealed to be

effective in preventing liver injury and liver failure. | (122) |

| Rumack, 2002 | The IV NAC dosing

regimen of 300 mg/kg infused over 21 h was approved by the

FDA. | (123) |

| Yarema, 2009 | When NAC was

initiated within 12 h, the relative risk of hepatotoxicity was

lower in the IV group vs. the oral group. | (124) |

| Yang, 2009 | Long-term NAC

treatment was revealed to impair APAP-induced liver regeneration in

patients with ALI, at least in part by inhibiting the NF-κB

activation pathway. | (125) |

| Blieden, 2010 | Common side

effects, such as nausea and vomiting, were reported to occur after

NAC treatment. | (126) |

| Saito, 2010 | The most effective

protective mechanism of NAC was revealed to be the enhancement of

hepatocyte clearance of NAPQI, which could prevent covalent

modification of cellular proteins, thereby blocking the initiation

of APAP toxicity. | (77) |

| Waring, 2012 | The side effects of

NAC were reported to be similar to the clinical manifestations of

allergic reactions, including rash, pruritus, angioedema and

bronchospasm. | (127) |

| de Andrade,

2015 | NAC was revealed to

attenuate hepatic injury inflammation during APAP-induced

hepatotoxicity and to exert antioxidant effects. | (128) |

| Khayyat, 2016 | After NAC

treatment, GSH was significantly elevated in an APAP-treated group;

the protective effect of NAC may occur by its promotion of GSH

biosynthesis. | (129) |

| Downs, 2021 | A standard dose of

NAC was sufficient to prevent 91% of hepatotoxicity in a large

number of patients with APAP overdose treated with NAC within 8

h. | (130) |

In the United States, the approved dose of oral NAC

is 140 mg/kg body weight followed by 70 mg/kg body weight every 4 h

for a total of 17 doses (81);

however, the efficacy of NAC reduces in patients with advanced

disease or after a large overdose because the drug has often been

metabolized in the body for some time before the patient is

admitted to the clinic (39). A

series of adverse reactions can occur during NAC treatment; some

examples are intravenous NAC side effects such as allergic

reactions, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, fever,

headache, drowsiness and low blood pressure (82). These reactions mainly occur in the

first hour after NAC infusion, corresponding to the peak of NAC

concentration (83); therefore, a

drug that can prolong the therapeutic window period of NAC is

urgently awaited. Based on NAC trials, scientists have shown

through animal experiments that co-treatment of fomepizole (4MP)

with APAP can effectively prevent AILI (84,85);

4MP can strongly attenuate hepatic GSH depletion, and can almost

eliminate APAP-AD and all oxidative metabolites of APAP, suggesting

that it effectively inhibits CYP2E1 and largely prevents the

formation of NAPQI. 4MP may be considered a good candidate for

NAC-assisted treatment of patients with selective APAP overdose

(33).

Activation of autophagy

Autophagy is the conserved process by which

substrates in the cytoplasm are translocated to lysosomes through

intermediate double-membrane-bound vesicles called autophagosomes

(86). It is a tightly regulated

cellular process that is essential for the maintenance of cellular

homeostasis through lysosomal degradation to remove unwanted

cytoplasmic contents, including misfolded or aggregated proteins,

accumulated lipids, excessive or damaged organelles, and harmful

pathogens (87), in order to

achieve cell renewal (88). It has

been demonstrated that APAP treatment induces the formation of

autophagosomes in mouse livers and that autophagy defects enhance

hepatocyte apoptosis and necrotic cell death resulting from APAP

treatment, a process that relies on MPTP opening, depolarization of

mitochondrial membranes, swelling and loss of proteins such as

cytochrome c (89).

Mitochondrial damage is a key event in APAP

hepatotoxicity. Autophagy selectively removes damaged organelles,

especially mitochondria, thereby preventing oxidative stress and

necrotic cell death caused by mitochondrial damage (90). This process is largely dependent on

a mitochondrial serine/threonine kinase (PINK1). In healthy

mitochondria, the mitochondrial transmembrane potential drives

PINK1 into the IMM via outer mitochondrial membrane translocase;

mitochondrial damage induces the accumulation of PINK1, which

recruits Parkin to initiate mitosis. Activated Parkin mediates

ubiquitination of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins, which acts

as a signal to recruit autophagy aptamers, such as OPTN, NDP52 and

p62. As a result, the autophagy machinery is recruited to degrade

damaged mitochondria (91). Excess

APAP can activate autophagy in mouse livers and primary hepatocytes

for protective purposes, which can counteract the mitochondrial

oxidative stress induced by APAP and JNK activation, among others

(92). Mechanistically, this is

likely a compensatory response to excess ROS after APAP

intoxication, and in this regard, mitochondria are the main source

of ROS required for autophagy-inducing signaling; ROS accumulation

can induce autophagy by directly affecting core autophagy

mechanisms and indirectly affecting components of

autophagy-regulated signaling pathways (93). Considering that the accumulation of

APAP-AD is an early and critical step in mitochondrial damage, the

formation of such adducts poses a potential threat to mitochondria.

Therefore, timely and effective removal of APAP-AD may be an

important strategy to alleviate the toxic effects of APAP on

mitochondria, thus maintaining their normal function, ensuring

smooth intracellular energy metabolism, and providing sufficient

ATP for cells. Autophagy can selectively remove deleterious

APAP-AD, thereby protecting the liver from AILI to a certain extent

(89). Furthermore, activated

autophagy can remove damaged mitochondria, which are the sites of

ROS production; elevated ROS levels can induce autophagy. Removal

of damaged mitochondria can reduce ROS production and eliminate

inflammatory vesicles (e.g., NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles),

potentially inhibiting inflammatory responses and maintaining the

normal turnover and regulatory functions of the ER (94).

Activation of the nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway and

inhibition of ferroptosis

Nrf2 is involved in various aspects of cellular and

organismal detoxification against oxidative stress, regulation of

cellular metabolism and promotion of cellular proliferation, and

serves a crucial role in the pathological mechanisms of several

diseases as well as homeostasis (95). The Nrf2 pathway is considered to

have a key role in AILI, and activation of Nrf2 signaling is a

potential target for ameliorating APAP hepatotoxicity. NAPQI, the

intermediate metabolite produced by APAP, contributes to GSH

depletion and ROS formation; this triggers oxidative stress, which

leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, hepatocyte necrosis and liver

injury (70). To counteract

oxidative stress induced by ROS, the body maintains cellular redox

homeostasis through a series of antioxidant molecules and

detoxifying enzymes. The Nrf2/ARE pathway is one of the major

nuclear transcription factor-associated mechanisms that respond to

this process by activating phase II detoxification enzymes; Nrf2

can detoxify NAPQI by activating antioxidant enzymes (96). GCL, a key enzyme in GSH synthesis,

consists of catalytic (GCLC) and modifying subunits; GCLC is one of

the downstream targets of Nrf2 activation (97).

Iron-dependent cell death (ferroptosis) is a

regulated form of cell death that can be induced when intracellular

GPX4 is directly or indirectly inhibited by low GSH levels

(98). APAP has been extensively

studied and shown to induce hepatic lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis, a cascading effect that ultimately leads to ALF in

mice (99). Notably, APAP-induced

ALF may be prevented by pharmacological and genetic inhibition of

ferroptosis, which acts as an initial event during the course of

APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and is not only capable of directly

damaging hepatocytes, but also triggers the release of

extracellular substances, such as DAMPs, that further exacerbate

inflammatory responses and intensify liver injury. Inhibition of

the Nrf2 pathway increases sensitivity to ferroptosis and GPX4 is a

downstream target of Nrf2 (100).

Several natural small-molecule drugs can activate the Nrf2 pathway,

and typically exhibit better biocompatibility and lower side

effects than conventional chemical drugs; they are of natural

origin, easily accessible and cost-effective. For example,

curcumin, a plant polyphenol extracted from turmeric, has been

shown to upregulate the expression of antioxidant enzymes, such as

GPX4, by promoting the release and activation of Nrf2, thereby

attenuating ferroptosis and alleviating APAP-induced

hepatotoxicity; this finding provides a new strategy and direction

for the treatment of APAP-induced ALF (101). Research progress on natural

small-molecule drugs for attenuating AILI has been summarized in

Table II, which lists the names

and mechanisms of action of various natural small-molecule drugs,

providing valuable references for researchers and clinicians.

| Table II.Advances in the study of natural

small molecule drug substances to ameliorate APAP liver injury. |

Table II.

Advances in the study of natural

small molecule drug substances to ameliorate APAP liver injury.

| First author,

year | Small molecule

drug | Mechanism | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Cai, 2022 | ASX | ASX ameliorated

AILI in vivo and in vitro by reducing inflammation,

inhibiting oxidative stress and ferroptosis via the NF-κB pathway,

and increasing autophagy via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. | (101) |

| Li, 2023 | KA | KA activated the

Nrf2 signaling pathway and inhibited ferroptosis. KA pretreatment

improved biochemical indices related to liver function, and

attenuated liver necrosis and inflammation in APAP-induced

mice. | (97) |

| Pang, 2016 | CA | CA prevented

APAP-induced hepatotoxicity by decreasing the expression of Keap1

and inhibiting the binding of Keap1 to Nrf2, which activated Nrf2,

leading to increased expression of antioxidant signaling. | (131) |

| Yang, 2020 | Limonin | Limonin attenuated

APAP-induced hepatotoxicity by activating the Nrf2 antioxidant

pathway and inhibiting the NF-κB inflammatory response through

upregulation of Sirt1. | (132) |

| An, 2023 | Abietic acid | Abietic acid

inhibited APAP-induced NF-κB activation, and increased Nrf2 and

HO-1 expression. In vitro, the inhibitory effects of Abietic

acid on APAP-induced inflammation and iron death were reversed when

Nrf2 was knocked down. | (133) |

| Lv, 2019 | Coriandrin | Coriandrin could

counteract APAP-induced ALF by inducing Nrf2 via the AMPK/GSK3β

pathway. | (134) |

| Wang, 2016 | EsA | EsA enhanced

Nrf2-regulated survival mechanisms through the AMPK/Akt/GSK3β

pathway and has been shown to possess protective potential against

APAP toxicity. | (135) |

| Wang, 2019 | Fariro | Activation of Nrf2

and induction of autophagy by Fariro through the AMPK/AKT pathway

contributed to its hepatoprotective activity in vitro, and

had protective potential against APAP-induced hepatotoxicity. | (96) |

| Zhu, 2023 | Xanthohumol | Xanthohumol

inhibited APAP-induced liver injury by suppressing oxidative stress

and mitochondrial dysfunction through activation of Nrf2 by

AMPK/Akt/GSK3β. | (136) |

| Yao, 2022 | Rosmarinic

acid | Rosmarinic acid was

shown to protect against AILI through Nrf2-mediated inhibition of

the NEK7-NLRP3 signaling pathway. | (137) |

| Jiang, 2022 | Sarmentosin | Sarmentosin

attenuated APAP-induced ALF and protected hepatocytes from APAP

injury in mice, and the important role of Nrf2-mediated oxidative

stress in the dynamics of this process was demonstrated. | (138) |

Liver repair and regeneration

Liver regeneration is a compensatory and beneficial

process in response to hepatocyte death and tissue damage;

stimulating this process may be a potential therapeutic strategy to

control APAP hepatotoxicity (102). The role played by innate immune

cells in APAP hepatotoxicity has been controversial, but evidence

has emphasized that innate immune cells are critical for liver

repair (103). Immune cells, such

as neutrophils and macrophages, stay mainly in necrotic areas after

APAP overdose; hepatic neutrophil infiltration is a key step of the

innate immune response to acute liver injury (104) and is critical for recovery after

APAP overdose (105). In

addition, platelets serve a key role in the course of AILI and

platelet depletion can attenuate hepatic injury to some extent.

Platelet-expressed c-type lectin-like receptor (CLEC)-2 is a key

mediator of platelet activation, and CLEC-2-mediated elimination of

platelet signaling may enhance recovery after acute liver injury

via TNF-α-dependent hepatic recruitment of neutrophils (103). In this context, neutrophil

infiltration represents an innate immune repair response that can

aid in rapid liver repair after acute injury.

Hepatocytes have a major role in the process of

liver regeneration. Liver recovery after APAP hepatotoxicity

involves a combination of numerous factors, such as hepatic

microvascular reconstruction and interactions between different

cell types. Among these factors, vascular endothelial growth factor

(VEGF), a major regulator of tumorigenesis, inflammation and wound

healing, can effectively promote liver regeneration (106). Cellular crosstalk between LSECs

and hepatocytes during liver regeneration serves an important role

in hepatic sinusoidal homeostasis and physiological angiogenesis

(107). A comparison of VEGF

receptor 1 (VEGFR1) tyrosine kinase-knockout (VEGFR1 TK2/2) and

wild-type (WT) mice revealed that the expression levels of

proliferating cell nuclear antigen and growth factors, such as

hepatocyte growth factor, CD31 and basic fibroblast growth factor,

were lower in the knockout mice than in WT mice. In addition, the

VEGFR1 TK2/2 mice showed impaired hepatic microvascular function,

which was reduced by ~40% compared with that in WT mice, a

phenomenon that was associated with enhanced hepatic MMP-9

expression (108). Selective

activation of VEGFR1 could serve as a target to promote tissue

repair by facilitating blood sinusoidal cell recovery after acute

liver injury; however, several risks are associated with VEGFR1

activation. Its activation on endothelial cells can promote

malignant angiogenesis, thereby enhancing the migration and

activity of endothelial cells, which may facilitate the invasion of

hepatocellular carcinoma cells (109).

Liver transplant

Hepatotoxicity can be completely prevented if NAC is

administered within 10 h of overdose. Patients who do not receive

NAC in time can develop severe liver injury, which may progress to

ALF. Therefore, in cases of severe liver injury caused by APAP,

liver transplantation may be the only treatment option to save the

life of the patient (110).

Moreover, liver transplantation is the only effective strategy for

the treatment of APAP-induced liver failure (111). The decision to undergo liver

transplantation for APAP overdose-induced ALF is challenging and

may be affected by the scarcity of donor liver grafts, acute graft

rejection, lifelong immunosuppression and unaffordable costs.

Psychosocial issues of patients with APAP overdose are of concern,

as >30% of those who meet the criteria for transplantation have

severe mental illness, or alcohol and/or drug abuse problems

(112).

Discussion

The prognosis of AILI is influenced by multiple

factors. APAP, a widely used analgesic and antipyretic, has become

a major cause of ALF in several countries and AILI is a major

public health problem worldwide. The causes of APAP intoxication

can be divided into two categories. For the first cause, i.e.,

self-administered overdose, patients are taken to the emergency

room for NAC treatment early and serious injury can be avoided. In

the other category, i.e., accidental overdoses, the optimal time

for treatment is often missed before an adverse reaction sets in

because the symptoms of poisoning are not obvious in the early

stages (24). The total ingested

dose of APAP is the most important determinant of the development

and severity of APAP-induced hepatotoxicity. The Rumack-Matthew

nomogram, developed in the 1970s as a tool for assessing the risk

of hepatotoxicity after ingestion of APAP, consists of two main

lines: The Treatment Line and the Rumack-Matthew Line, which

predict the risk of hepatotoxicity from 4 to 24 h after ingestion.

However, this chart does not apply to patients tested 24 h after

ingestion or with a history of multiple ingestions (113). In addition, patterns of use and

certain factors [e.g., chronic alcohol abuse (114), age, concomitant use of certain

medications, genetic factors, pre-existing liver disease and

nutritional status] can influence susceptibility to APAP

hepatotoxicity via multiple mechanisms (115). For example, a study of 1,039

children aged <7 years found no susceptibility to APAP-induced

hepatotoxicity after mild to moderate (up to 200 mg/kg) APAP

ingestion (116). This

observation could be explained by the fact that the sulfate

coupling of the drug is more pronounced in children, whereas the

glucuronide coupling is more predominant in adults, which means

that differences in the binding pathways may result in a reduced

risk of APAP-related toxicity in children. In addition, because

NAPQI formation is dependent on APAP metabolism via the CYP system

and coupling to mercapturic acid metabolites after therapeutic

doses, urinary concentrations of these metabolites are much lower

in children than in adults. This suggests that CYP serves a less

significant role in APAP metabolism in children than in adults

(117). Timely medical

intervention, such as the clinical application of NAC, can minimize

liver injury.

Research on the epidemiology, mechanism underlying

toxicity, diagnosis and treatment of AILI has progressed

considerably. However, some persistent challenges include the early

diagnosis of APAP-induced hepatotoxicity (when it is not clinically

apparent) to avoid severe injury later, and the identification of

safe doses for different populations in terms of their

sensitivities. Since LSEC damage often occurs in the early stages

of liver injury, it could be proposed that the detection of

LSEC-specific damage may provide a timely and accurate diagnosis of

patients when conventional markers, such as ALT and AST, do not

show notable changes. For example, changes in their morphology can

be observed by electron microscopy; in normal liver samples, the

thin and weak cytoplasm of LSECs contains a large number of pores,

which is its unique structure (118). However, when the liver is

diseased, the size of the pores will gradually change; for example,

in liver fibrosis, the pores will disappear progressively until a

continuous basement membrane is formed (119). To achieve this goal, future

studies are required to explore the specific relationship between

LSEC injury and APAP hepatotoxicity, and to develop more sensitive

and specific assays.

In conclusion, research on AILI is continuously

advancing, and researchers are exploring the mechanisms of

toxicity, biomarkers, therapeutic targets and new therapeutic

approaches from multiple perspectives. The results of these

research studies are expected to provide new ideas and methods for

the prevention and treatment of DILI, and to further reduce the

risk of liver injury caused by APAP and other drugs.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

RL and HL designed the subject of review. RL, HL,

HW, YuX, XX, YiX, HH, XL, CL and JY participated in writing and

reviewing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the

final manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hoofnagle JH and Björnsson ES:

Drug-induced liver injury-types and phenotypes. N Engl J Med.

381:264–273. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shen T, Liu Y, Shang J, Xie Q, Li J, Yan

M, Xu J, Niu J, Liu J, Watkins PB, et al: Incidence and etiology of

drug-induced liver injury in mainland China. Gastroenterology.

156:2230–2241.e11. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Es B: The epidemiology of newly recognized

causes of drug-induced liver injury: An update. Pharmaceuticals

(Basel). 17:5202024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Warnet JM, Bakar-Wesseling I, Thevenin M,

Serrano JJ, Jacqueson A, Boucard M and Claude JR: Effects of

subchronic low-protein diet on some tissue glutathione-related

enzyme activities in the rat. Arch Toxicol Suppl. 11:45–49.

1987.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Andrade RJ, Chalasani N, Björnsson ES,

Suzuki A, Kullak-Ublick GA, Watkins PB, Devarbhavi H, Merz M,

Lucena MI, Kaplowitz N and Aithal GP: Drug-induced liver injury.

Nat Rev Dis Primers. 5:582019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kjartansdottir I, Bergmann OM and

Arnadottir RS: Paracetamol intoxications: A retrospective

population-based study in iceland. Scand J Gastroenterol.

47:1344–1352. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tan ST, Lo CH, Liao CH and Su YJ:

Sex-based differences in the predisposing factors of overdose: A

retrospective study. Biomed Rep. 16:492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Paulose-Ram R, Hirsch R, Dillon C,

Losonczy K, Cooper M and Ostchega Y: Prescription and

non-prescription analgesic use among the US adult population:

Results from the third national health and nutrition examination

survey (NHANES III). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 12:315–326. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rubin JB, Hameed B, Gottfried M, Lee WM

and Sarkar M; Acute Liver Failure Study Group, :

Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure is more common and more

severe in women. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:936–946. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang X, Wu Q, Liu A, Anadón A, Rodríguez

JL, Martínez-Larrañaga MR, Yuan Z and Martínez MA: Paracetamol:

Overdose-induced oxidative stress toxicity, metabolism, and

protective effects of various compounds in vivo and in vitro. Drug

Metab Rev. 49:395–437. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Brune K, Renner B and Tiegs G:

Acetaminophen/paracetamol: A history of errors, failures and false

decisions. Eur J Pain. 19:953–965. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chidiac AS, Buckley NA, Noghrehchi F and

Cairns R: Paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose and hepatotoxicity:

Mechanism, treatment, prevention measures, and estimates of burden

of disease. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 19:297–317. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Davidson DG and Eastham WN: Acute liver

necrosis following overdose of paracetamol. Br Med J. 2:497–499.

1966. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

McGill MR and Hinson JA: The development

and hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen: Reviewing over a century of

progress. Drug Metab Rev. 52:472–500. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Dart RC, Erdman AR, Olson KR, Christianson

G, Manoguerra AS, Chyka PA, Caravati EM, Wax PM, Keyes DC, Woolf

AD, et al: Acetaminophen poisoning: An evidence-based consensus

guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clin Toxicol (Phila).

44:1–18. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Chiew AL, Isbister GK, Stathakis P,

Isoardi KZ, Page C, Ress K, Chan BSH and Buckley NA: Acetaminophen

metabolites on presentation following an acute acetaminophen

overdose (ATOM-7). Clin Pharmacol Ther. 113:1304–1314. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Rumack BH, Peterson RC, Koch GG and Amara

IA: Acetaminophen overdose. 662 cases with evaluation of oral

acetylcysteine treatment. Arch Intern Med. 141:380–385. 1981.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Singer AJ, Carracio TR and Mofenson HC:

The temporal profile of increased transaminase levels in patients

with acetaminophen-induced liver dysfunction. Ann Emerg Med.

26:49–53. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Larson AM: Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity.

Clin Liver Dis. 11:525–548. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ramachandran A and Jaeschke H:

Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Semin Liver Dis. 39:221–234. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ma J, Li M, Li N, Chan WY and Lin G:

Pyrrolizidine alkaloid-induced hepatotoxicity associated with the

formation of reactive metabolite-derived pyrrole-protein adducts.

Toxins. 13:7232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

McGill MR and Jaeschke H: Mechanistic

biomarkers in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity and acute liver

failure: From preclinical models to patients. Expert Opin Drug

Metab Toxicol. 10:1005–1017. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nelson SD: Molecular mechanisms of the

hepatotoxicity caused by acetaminophen. Semin Liver Dis.

10:267–278. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lee WM: Acetaminophen (APAP)

hepatotoxicity-isn't it time for APAP to go away? J Hepatology.

67:1324–1331. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Huang XP, Thiessen JJ, Spino M and

Templeton DM: Transport of iron chelators and chelates across MDCK

cell monolayers: Implications for iron excretion during chelation

therapy. Int J Hematol. 91:401–412. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Letelier ME, López-Valladares M,

Peredo-Silva L, Rojas-Sepúlveda D and Aracena P: Microsomal

oxidative damage promoted by acetaminophen metabolism. Toxicol In

Vitro. 25:1310–1313. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hinson JA, Pumford NR and Roberts DW:

Mechanisms of acetaminophen toxicity: Immunochemical detection of

drug-protein adducts. Drug Metab Rev. 27:73–92. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ramachandran A and Jaeschke H: A

mitochondrial journey through acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Food

Chem Toxicol. 140:1112822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

McGill MR, Sharpe MR, Williams CD, Taha M,

Curry SC and Jaeschke H: The mechanism underlying

acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in humans and mice involves

mitochondrial damage and nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Clin Invest.

122:1574–1583. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Nguyen NU and Stamper BD: Polyphenols

reported to shift APAP-induced changes in MAPK signaling and

toxicity outcomes. Chem Biol Interact. 277:129–136. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Nakagawa H, Maeda S, Hikiba Y, Ohmae T,

Shibata W, Yanai A, Sakamoto K, Ogura K, Noguchi T, Karin M, et al:

Deletion of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 attenuates

acetaminophen-induced liver injury by inhibiting c-jun N-terminal

kinase activation. Gastroenterology. 135:1311–1321. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Thévenin AF, Zony CL, Bahnson BJ and

Colman RF: GST pi modulates JNK activity through a direct

interaction with JNK substrate, ATF2. Protein Sci. 20:834–848.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Akakpo JY, Ramachandran A, Curry SC, Rumac

BH and Jaeschke H: Comparing N-acetylcysteine and 4-methylpyrazole

as antidotes for acetaminophen overdose. Arch Toxicol. 96:453–465.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Moles A, Torres S, Baulies A, Garcia-Ruiz

C and Fernandez-Checa JC: Mitochondrial-lysosomal axis in

acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Front Pharmacol. 9:4532018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Xu Y, Xia Y, Liu Q, Jing X, Tang Q, Zhang

J, Jia Q, Zhang Z, Li J, Chen J, et al: Glutaredoxin-1 alleviates

acetaminophen-induced liver injury by decreasing its toxic

metabolites. J Pharm Anal. 13:1548–1561. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chowdhury A, Lu J, Zhang R, Nabila J, Gao

H, Wan Z, Adelusi Temitope I, Yin X and Sun Y: Mangiferin

ameliorates acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity through APAP-cys

and JNK modulation. Biomed Pharmacother. 117:1090972019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Jaeschke H, Adelusi OB, Akakpo JY, Nguyen

NT, Sanchez-Guerrero G, Umbaugh DS, Ding WX and Ramachandran A:

Recommendations for the use of the acetaminophen hepatotoxicity

model for mechanistic studies and how to avoid common pitfalls.

Acta Pharm Sin B. 11:3740–3755. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Radi R, Peluffo G, Alvarez MN, Naviliat M

and Cayota A: Unraveling peroxynitrite formation in biological

systems. Free Radic Biol Med. 30:463–488. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Cover C, Mansouri A, Knight TR, Bajt ML,

Lemasters JJ, Pessayre D and Jaeschke H: Peroxynitrite-induced

mitochondrial and endonuclease-mediated nuclear DNA damage in

acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 315:879–887.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Saito C, Lemasters JJ and Jaeschke H:

c-jun N-terminal kinase modulates oxidant stress and peroxynitrite

formation independent of inducible nitric oxide synthase in

acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 246:8–17.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kon K, Kim JS, Uchiyama A, Jaeschke H and

Lemasters JJ: Lysosomal iron mobilization and induction of the

mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced

toxicity to mouse hepatocytes. Toxicol Sci. 117:101–108. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Jaeschke H, Ramachandran A, Chao X and

Ding WX: Emerging and established modes of cell death during

acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Arch Toxicol. 93:3491–3502.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Bajt ML, Farhood A, Lemasters JJ and

Jaeschke H: Mitochondrial bax translocation accelerates DNA

fragmentation and cell necrosis in a murine model of acetaminophen

hepatotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 324:8–14. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Li GW, Liu J and Chen L: Continuous

ambulatory peritoneal dialysis treatment and blood glucose control

in diabetics with end-stage diabetic nephropathy. Zhonghua Nei Ke

Za Zhi. 28:360–363. 3821989.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yoon E, Babar A, Choudhary M, Kutner M and

Pyrsopoulos N: Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity: A

comprehensive update. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 4:131–142.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Knight TR, Ho YS, Farhood A and Jaeschke

H: Peroxynitrite is a critical mediator of acetaminophen

hepatotoxicity in murine livers: Protection by glutathione. J

Pharmacol Exp Ther. 303:468–475. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Gracia-Sancho J, Marrone G and

Fernández-Iglesias A: Hepatic microcirculation and mechanisms of

portal hypertension. Nat Rev Gastroenterol. 16:221–234. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Gracia-Sancho J, Caparrós E,

Fernández-Iglesias A and Francés R: Role of liver sinusoidal

endothelial cells in liver diseases. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

18:411–431. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

McCuskey RS, Bethea NW, Wong J, McCuskey

MK, Abril ER, Wang X, Ito Y and DeLeve LD: Ethanol binging

exacerbates sinusoidal endothelial and parenchymal injury elicited

by acetaminophen. J Hepatol. 42:371–377. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Ito Y, Bethea NW, Abril ER and McCuskey

RS: Early hepatic microvascular injury in response to acetaminophen

toxicity. Microcirculation. 10:391–400. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

McCuskey RS: Sinusoidal endothelial cells

as an early target for hepatic toxicants. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc.

34:5–10. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Walker RM, Racz WJ and McElligott TF:

Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxic congestion in mice. Hepatology.

5:233–240. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Damen L, Bruijn JKJ, Verhagen AP, Berger

MY, Passchier J and Koes BW: Symptomatic treatment of migraine in

children: A systematic review of medication trials. Pediatrics.

116:e295–e302. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Williams AM, Langley PG, Osei-Hwediah J,

Wendon JA and Hughes RD: Hyaluronic acid and endothelial damage due

to paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity. Liver Int. 23:110–115. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

DeLeve LD, Wang X, Kaplowitz N, Shulman

HM, Bart JA and van der Hoek A: Sinusoidal endothelial cells as a

target for acetaminophen toxicity. Direct action versus requirement

for hepatocyte activation in different mouse strains. Biochem

Pharmacol. 53:1339–1345. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Walter P and Ron D: The unfolded protein

response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science.

334:1081–1086. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Maytin EV, Ubeda M, Lin JC and Habener JF:

Stress-inducible transcription factor CHOP/gadd153 induces

apoptosis in mammalian cells via p38 kinase-dependent and

-independent mechanisms. Exp Cell Res. 267:193–204. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Lee DH, Lee B, Park JS, Lee YS, Kim JH,

Cho Y, Jo Y, Kim HS, Lee YH, Nam KT and Bae SH: Inactivation of

Sirtuin2 protects mice from acetaminophen-induced liver injury:

Possible involvement of ER stress and S6K1 activation. BMB Rep.

52:190–195. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kalinec GM, Thein P, Parsa A, Yorgason J,

Luxford W, Urrutia R and Kalinec F: Acetaminophen and NAPQI are

toxic to auditory cells via oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum

stress-dependent pathways. Hear Res. 313:26–37. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhang X, Xiong W, Chen LL, Huang JQ and

Lei XG: Selenoprotein V protects against endoplasmic reticulum

stress and oxidative injury induced by pro-oxidants. Free Radic

Biol Med. 160:670–679. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Uzi D, Barda L, Scaiewicz V, Mills M,

Mueller T, Gonzalez-Rodriguez A, Valverde AM, Iwawaki T, Nahmias Y,

Xavier R, et al: CHOP is a critical regulator of

acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. J Hepatol. 59:495–503. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Nagy G, Kardon T, Wunderlich L, Szarka A,

Kiss A, Schaff Z, Bánhegyi G and Mandl J: Acetaminophen induces ER

dependent signaling in mouse liver. Arch Biochem Biophys.

459:273–279. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Jaeschke H, Gujral JS and Bajt ML:

Apoptosis and necrosis in liver disease. Liver Int. 24:85–89. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Henderson CJ, Wolf CR, Kitteringham N,

Powell H, Otto D and Park BK: Increased resistance to acetaminophen

hepatotoxicity in mice lacking glutathione S-transferase pi. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 97:12741–12745. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Foufelle F and Fromenty B: Role of

endoplasmic reticulum stress in drug-induced toxicity. Pharmacol

Res Perspect. 4:e002112016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Xiao T, Liang X, Liu H, Zhang F, Meng W

and Hu F: Mitochondrial stress protein HSP60 regulates ER

stress-induced hepatic lipogenesis. J Mol Endocrinol. 64:67–75.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Mihm S: Danger-associated molecular

patterns (DAMPs): Molecular triggers for sterile inflammation in

the liver. Int J Mol Sci. 19:31042018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Sanz-Garcia C, Ferrer-Mayorga G,

González-Rodríguez Á, Valverde AM, Martín-Duce A, Velasco-Martín

JP, Regadera J, Fernández M and Alemany S: Sterile inflammation in

acetaminophen-induced liver injury is mediated by Cot/tpl2. J Biol

Chem. 288:15342–15351. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Jaeschke H, Williams CD, Ramachandran A

and Bajt ML: Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and repair: The role of

sterile inflammation and innate immunity. Liver Int. 32:8–20. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Jaeschke H and Ramachandran A:

Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: Paradigm for understanding mechanisms

of drug-induced liver injury. Ann Rev Pathol. 19:453–478. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Jaeschke H and Ramachandran A: Mechanisms

and pathophysiological significance of sterile inflammation during

acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 138:1112402020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Guo H, Chen S, Xie M and Zheng M: The

complex roles of neutrophils in APAP-induced liver injury. Cell

Prolif. 54:e130402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Krenkel O and Tacke F: Liver macrophages

in tissue homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 17:306–321.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Shan S, Shen Z and Song F: Autophagy and

acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Arch Toxicol. 92:2153–2161.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Mitchell JR, Jollow DJ, Potter WZ, Davis

DC, Gillette JR and Brodie BB: Acetaminophen-induced hepatic

necrosis. I. Role of drug metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther.

187:185–194. 1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Renzi FP, Donovan JW, Martin TG, Morgan L

and Harrison EF: Concomitant use of activated charcoal and

N-acetylcysteine. Ann Emerg Med. 14:568–572. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Saito C, Zwingmann C and Jaeschke H: Novel

mechanisms of protection against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in

mice by glutathione and N-acetylcysteine. Hepatology. 51:246–254.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Lasram MM, Dhouib IB, Annabi A, El Fazaa S

and Gharbi N: A review on the possible molecular mechanism of

action of N-acetylcysteine against insulin resistance and type-2

diabetes development. Clin Biochem. 48:1200–1208. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Jones AL: Mechanism of action and value of

N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of early and late acetaminophen

poisoning: A critical review. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 36:277–285.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Dell'Aglio DM, Sutter ME, Schwartz MD,

Koch DD, Algren DA and Morgan BW: Acute chloroform ingestion

successfully treated with intravenously administered

N-acetylcysteine. J Med Toxicol. 6:143–146. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Fisher ES and Curry SC: Evaluation and

treatment of acetaminophen toxicity. Adv Pharmacol. 85:263–272.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Park BK, Dear JW and Antoine DJ:

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning. BMJ Clin Evid.

2015:21012015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Licata A, Minissale MG, Stankevičiūtė S,

Sanabria-Cabrera J, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ and Almasio PL:

N-acetylcysteine for preventing acetaminophen-induced liver injury:

A comprehensive review. Front Pharmacol. 13:8285652022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Akakpo JY, Jaeschke MW, Ramachandran A,

Curry SC, Rumack BH and Jaeschke H: Delayed administration of

N-acetylcysteine blunts recovery after an acetaminophen overdose

unlike 4-methylpyrazole. Arch Toxicol. 95:3377–3391. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Akakpo JY, Ramachandran A, Rumack BH,

Wallace DP and Jaeschke H: Lack of mitochondrial Cyp2E1 drives

acetaminophen-induced ER stress-mediated apoptosis in mouse and

human kidneys: Inhibition by 4-methylpyrazole but not

N-acetylcysteine. Toxicology. 500:1536922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Matsuzawa-Ishimoto Y, Hwang S and Cadwell

K: Autophagy and inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 36:73–101. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Levine B and Klionsky DJ: Development by

self-digestion: Molecular mechanisms and biological functions of

autophagy. Dev Cell. 6:463–477. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Moore MN: Autophagy as a second level

protective process in conferring resistance to

environmentally-induced oxidative stress. Autophagy. 4:254–256.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Chao X, Wang H, Jaeschke H and Ding WX:

Role and mechanisms of autophagy in acetaminophen-induced liver

injury. Liver Int. 38:1363–1374. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Lee J, Giordano S and Zhang J: Autophagy,

mitochondria and oxidative stress: Cross-talk and redox signalling.

Biochem J. 441:523–540. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Khaminets A, Heinrich T, Mari M, Grumati

P, Huebner AK, Akutsu M, Liebmann L, Stolz A, Nietzsche S, Koch N,

et al: Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum turnover by selective

autophagy. Nature. 522:354–358. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Lin Z, Wu F, Lin S, Pan X, Jin L, Lu T,

Shi L, Wang Y, Xu A and Li X: Adiponectin protects against

acetaminophen-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and acute liver

injury by promoting autophagy in mice. J Hepatol. 61:825–831. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Rhodes DG, Sarmiento JG and Herbette LG: