Introduction

Carbonyl reductase 1 (CBR1), an NADPH-dependent

monomeric cytosolic enzyme with wide specificity for carbonyl

compounds (1), is expressed in the

intestinal tract, liver, kidneys, skin, and ovaries (2,3), where

it reduces carbonyl compounds such as anthracyclines, daunorubicin,

doxorubicin, and prostaglandins (3). Studies suggest that its primary

function is regulation of fatty acid metabolism (3).

CBR1 expression levels are associated with cancer

cell malignancy; for example, reduced expression is accompanied by

a fall in expression of E-cadherin along with activation of matrix

metalloproteinases, which promotes cell proliferation and

tumorigenesis of ovarian, cervical, and endometrial cancers in

vivo (4–6). Previously, we reported that the

prognosis for patients with ovarian cancer showing low expression

of CBR1 is worse than that of those with ovarian cancer

overexpressing CBR1 (4). In

addition, increased expression of CBR1 suppresses growth of ovarian

cancer cells (6), whereas decreased

expression promotes growth and metastasis (5). Our previous study also suggests that

increased expression of CBR1 in ovarian cancer cells may exert

antitumor effects by activating caspase pathways (6). CBR1 suppresses development of cervical

cancer, uterine sarcoma, and non-small cell lung carcinoma

(7–9). Taken together, these data suggest that

CBR1 regulates fatty acid metabolism and suppresses tumor growth

via different molecular mechanisms; however, the signaling cascades

affected by changes in CBR1 expression have not been examined in

detail.

Proteomics analysis involves systematic,

comprehensive, and quantitative identification of the proteins

(i.e., the proteome) present in a biological system (e.g., cells,

tissues, organs, fluids, and whole organisms) at a specific point

in time (10–12). The three main branches of proteomics

used to characterize the function and location of proteins are (I)

functional proteomics, (II) structural proteomics, and (III)

expression proteomics. The information obtained can be used to

predict new proteins involved in signal transduction and disease

pathogenesis (13). Therefore,

proteomics should be useful for elucidating the molecular

mechanisms affected by increased or decreased expression of

CBR1.

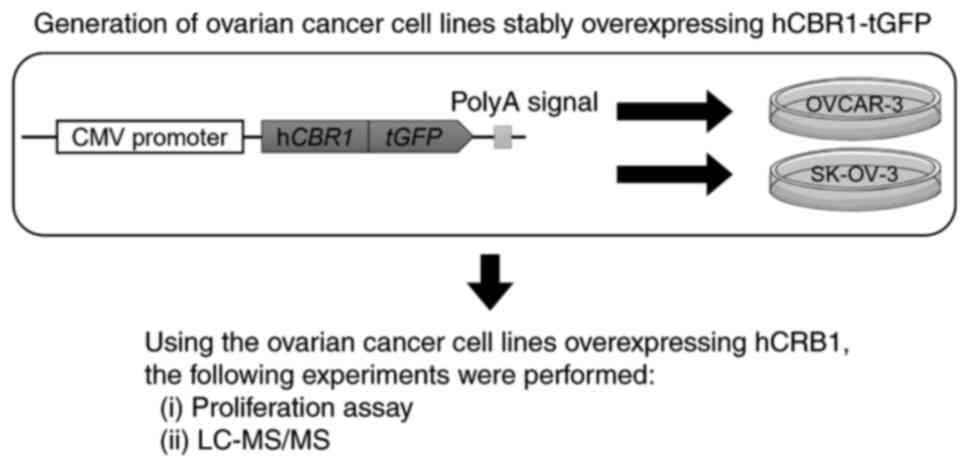

In this study, we used a proteomics analysis

approach to examine signaling cascades altered by stable

overexpression of CBR1 in ovarian cancer cells. The workflow of the

study is shown in Fig. 1. We

generated human ovarian cancer cell lines stably expressing human

CBR1 (hCBR1), and then investigated whether their growth was

inhibited. We then used liquid chromatography followed by mass

spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to identify the molecules/signaling

pathways affected.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

OVCAR-3 and SK-OV-3 cell lines were purchased from

the American Type Culture Collection (HTB-161 and HTB-77,

respectively; Rockville, MD, USA). These cell lines are derived

from human ovarian cancer cell tissue and are often used to

generate solid tumor xenografts (10,14–18).

The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St

Louis, MO, USA) at 37°C in a water-saturated atmosphere containing

5% CO2/95% air. The culture medium was supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (NICHIREI Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan), 100 U/ml

penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin.

Preparation of plasmid DNA

The pCMV6-AC-GFP-hCBR1 plasmid (RG204950, OriGene

Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) was used to generate

hCBR1-overexpressing cells. This plasmid encodes hCBR1 fused to

turbo green fluorescent protein (hCBR1-tGFP), which is expressed

under the control of the CMV promoter. Plasmid pCMV6-AC-GFP

(PS100010, OriGene Technologies, Inc.), which expresses tGFP, was

used to generate negative control cell lines.

Transfection of ovarian cancer

cells

Ovarian cancer cells were plated into a 10 cm dish

and cultured to 70–80% confluence. Cells were then transfected with

24 µg of pCMV6-AC-GFP-hCBR1 or pCMV6-AC-GFP using Lipofectamine

3000 (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA) for 24 h at 37°C.

Then, G418 (NACALAI TESQUE, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) was added (0.4

mg/ml) to the culture medium to select cell lines possessing the

plasmid DNA in their genome.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were homogenized on ice in

radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Fujifilm Wako,

Osaka, Japan) containing cOmplete Mini EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor

Cocktail Tablets provided in EASY packs (Roche, Basel,

Switzerland). Protein measurements were performed using Bio-Rad

Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins (8 µg) were loaded into the wells of

5–20% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Fujifilm Wako), electrophoresed, and

transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes

were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with Tris-buffered saline

(TBS) containing 0.05% Tween-20/1% skim milk or 2% bovine serum

albumin [for the anti-phospho-translation initiation factor 2

(eIF2)α blot] and then incubated overnight at 4°C with a polyclonal

rabbit anti-hCBR1 antibody (Ab) (1:1,000; ab-186825; Abcam,

Cambridge, UK), an anti-β-actin Ab (1:5,000; M177-3; MBL, Tokyo,

Japan), an anti-eIF2α Ab (1:5,000; 9722, Cell Signaling Technology,

Danvers, MA, USA), an anti-phospho-eIF2α (p-eIF2α) Ab (1:5,000;

9721, Cell Signaling Technology), and an anti-activating

transcription factor 4 (ATF4) Ab (1:1,000; ab-216839; Abcam). After

washing with TBS/0.05% Tween-20, the membranes were incubated for 1

h at room temperature with an appropriate horseradish peroxidase

(HRP)-conjugated secondary Ab [either anti-mouse IgG-HRP (NA9310V;

GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) or anti-rabbit IgG-HRP

(NA9340V; GE Healthcare)]. Protein bands were detected using

enhanced chemiluminescence (Image Quant LAS4000 system; GE

Healthcare). The detected bands were quantified using Image J

(19).

Evaluation of ovarian cancer cell

proliferation

Wild-type, negative control, and

hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing ovarian cancer cells were plated in 6 cm

dishes (1.0×104 cells/dish) and cultured at 37°C for 24, 48, 72,

96, or 120 h. Cells were then washed with 1 ml of Dulbecco's

phosphate-buffered saline and detached with 0.5 g/l-Trypsin/0.53

mmol/l-EDTA Solution (NACALAI TESQUE, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). Trypan

blue solution (0.1%; NACALAI TESQUE, Inc.) was used to discriminate

living from dead cells; cells were counted using a hemocytometer

(Bio Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan). The rate of cell growth was

calculated as the slope of a linear fit created by plotting the

natural logarithm of the cell number against culture time.

LC-MS/MS

Wild-type OVCAR-3 and five lots of OVCAR-3-derived

cells overexpressing CBR1 were cultured and sampled in triplicate.

Cell lysates were prepared as described for immunoblot analysis.

Label-free whole cell proteomic analysis was performed as described

previously (20). Briefly, cell

lysates containing 20 µg of total protein, as determined by the

bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method, were denatured with acetone. The

precipitates were then denatured with 50% trifluoroethanol.

Disulfide bonds were reduced with dithiothreitol (DTT) and

alkylated with iodoacetamide followed by trypsin digestion. After

desalting and purification of the resulting peptides using MonoSpin

C18 columns (GL Sciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan), the samples were

subjected to LC-MS/MS using a nanoLC system (Eksigent 400, AB

Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA) coupled online to a mass spectrometer

(TripleTOF6600, AB Sciex). Peptide separation was performed using

LC on a nano C18 reverse-phase capillary tip column (75 µm × 125

mm, 3 µm, Nikkyo Technos CO., Tokyo, Japan) at 300 nl/min with a 90

min linear gradient of 8–30% acetonitrile in 0.1% FA, and then,

with a 10 min linear gradient of 30 to 40% acetonitrile in 0.1% FA.

The mass spectrometer was operated in information-dependent

acquisition (IDA) and data-independent acquisition (SWATH) while in

positive ion mode, scanning full spectra (400-1,500 m/z) for 250

msec, followed by up to 30 MS/MS scans (100-1,800 m/z for 50 msec

each), for a cycle time of 1.8 sec. Candidate ions with a charge

state between +2 and +5 and counts above a minimum threshold of 125

counts per second were isolated for fragmentation, and one MS/MS

spectrum was collected before adding those ions to the exclusion

list for 12 sec. For SWATH acquisition, the parameters were set as

follows: 100 msec TOF MS scan, followed by 200 variable SWATH

windows each at 50 msec accumulation time for m/z 400-1,250. MS/MS

SWATH scans were set at 5 Da window overlapping by 1 Da for m/z

400-1,250 and varied on each side of the mass range. The total

cycle time was 9.6 sec. A rolling collision energy parameters

script was used to automatically control the collision energy.

Database searching for acquired spectra was performed using

ProteinPilot 5.0.1 software (AB Sciex). The positive identification

threshold was set at a false discovery rate of 1% or less. The

resulting library file and SWATH (data independent acquisition)

files were processed by PeakView (ver. 2.2.0, AB Sciex) and

exported to MarkerView (ver. 1.3.0.1; AB Sciex). The peak area of

individual proteins was normalized relative to the sum of the peak

areas of all detected proteins.

Statistical analysis and

reproducibility

Experiments were performed in triplicate for

immunoblot analysis and evaluation of ovarian cancer cell

proliferation. Normal distribution was tested by Shapiro-Wilk test.

Statistical differences between the three groups

(hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing, negative control, and wild-type cells)

were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test

(parametric data) or Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric data).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS

ver. 29.0 statistics software (IBM, Chicago, Illinois).

Regarding the statistical analysis of the proteome

data, principal component analysis using SIMCA software (version

15.0.2, Infocom Corp., Tokyo, Japan) confirmed that there was no

outlier proteome in any of the samples. Since the cell lines used

show endogenous CBR1 expression, proteins covarying with CBR1 were

subjected to Spearman's rank correlation analysis and Pearson's

correlation analysis (R version 4.1.0 software) to capture

proteomic variations due to CBR1 transfection. Proteins with

FDR-adjusted P<0.05 were identified as proteins covarying with

CBR1 and subjected to pathway enrichment and network analysis by

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software (Qiagen, Venlo,

Netherland).

Results

Generation of ovarian cancer cells

stably expressing hCBR1-tGFP

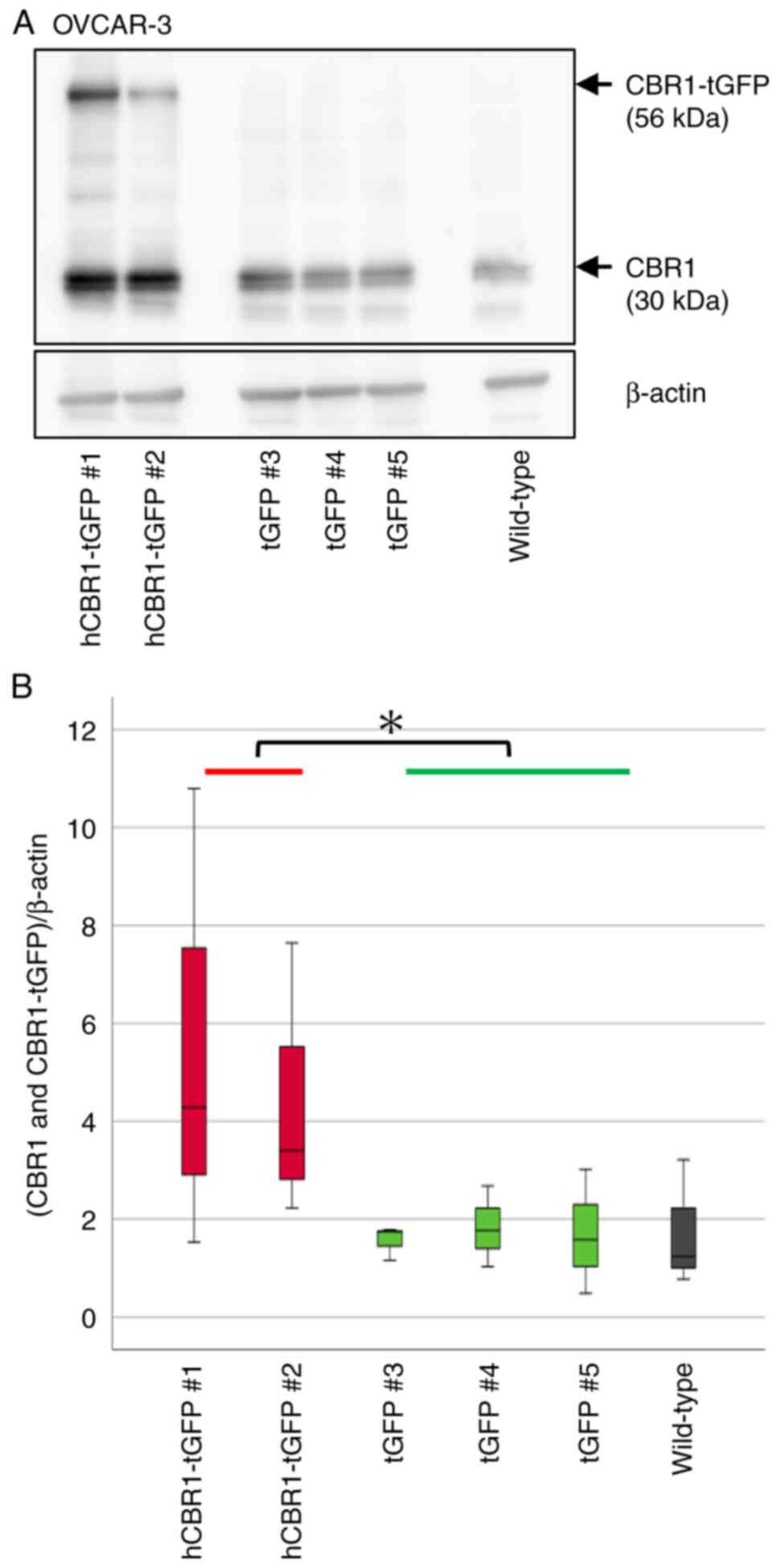

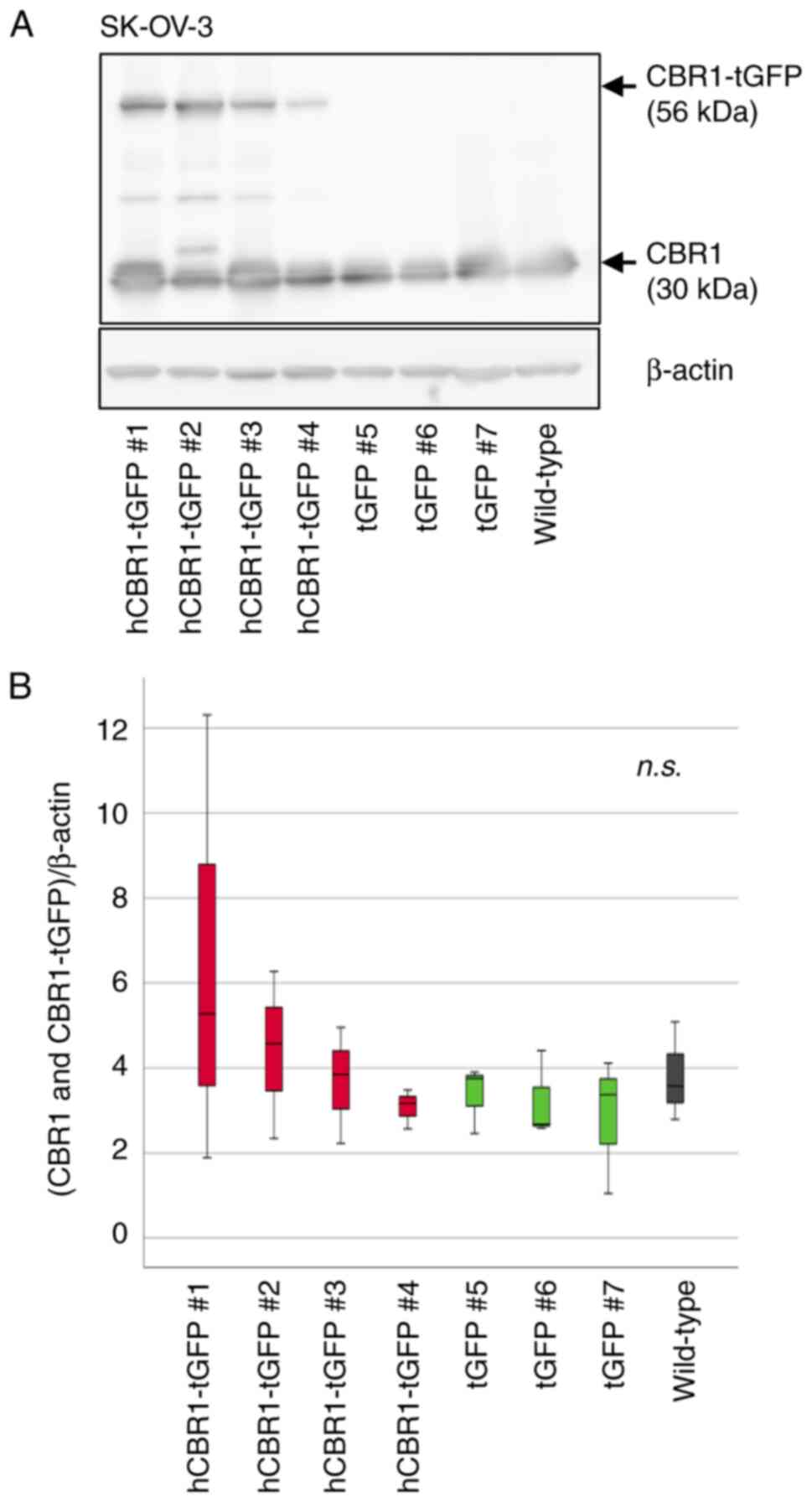

To investigate the role of CBR1 on the malignancy of

ovarian cancer cells, we first generated OVCAR-3 and SK-OV-3 cell

lines stably expressing hCBR1-tGFP. We also generated ovarian

cancer cells expressing only tGFP as a control (negative control

cells). Immunoblot analysis using an anti-CBR1 Ab revealed stable

expression of hCBR1-tGFP (Figs. 2A

and 3A). A band corresponding to

hCBR1-tGFP was not observed in the negative control and wild-type

cell samples. We measured CBR1 protein expression levels (i.e., the

combined expression levels of hCBR1-tGFP and CBR1) in OVCAR-3 and

SK-OV-3 cells using image analysis software (Figs. 2B and 3B). The results confirmed that expression

of CBR1 protein in hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing OVCAR-3 cells was

significantly higher than that in wild-type and negative control

cells (Fig. 2B). As to SK-OV-3

cells, hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing cell #1 and #2 showed the highest

and relatively high expression of CBR1 protein, respectively

(Fig. 3B). Although all

hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing SK-OV-3 cells showed hCBR1-tGFP

expression (Fig. 3A), the

expression was slight in the cell line #4. Therefore, statistical

significance on the total CBR1 amount was not observed among cell

groups (Fig. 3B). Nevertheless,

hCBR1-tGFP was visibly expressed in the cell line #4, and the other

hCBR1-tGFP-expressing cells show a tendency of upregulation of

total hCBR1 protein. To examine the importance of the CBR1 protein

in ovarian cancer cells, these established SK-OV-3 cells were also

used for subsequent experiments.

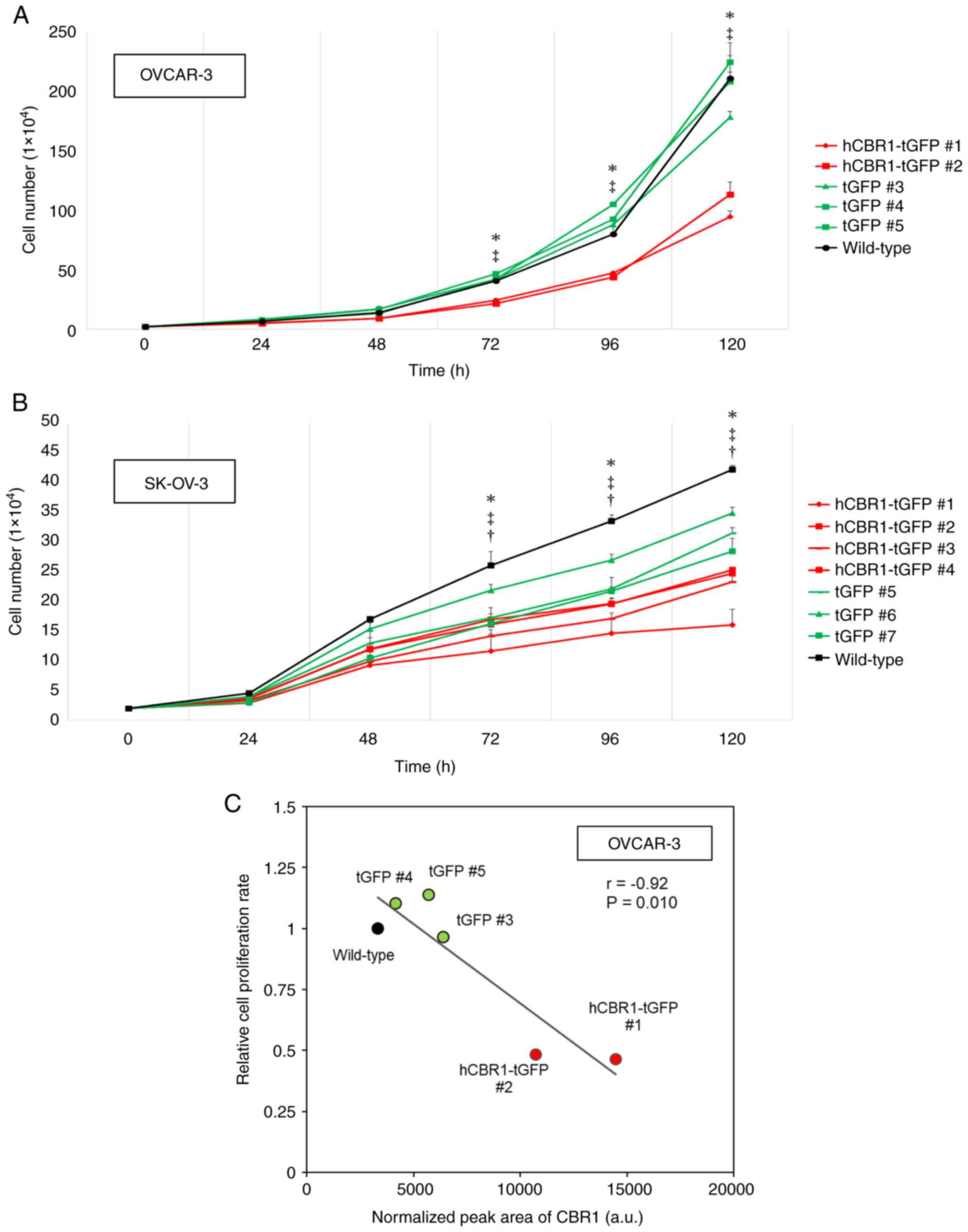

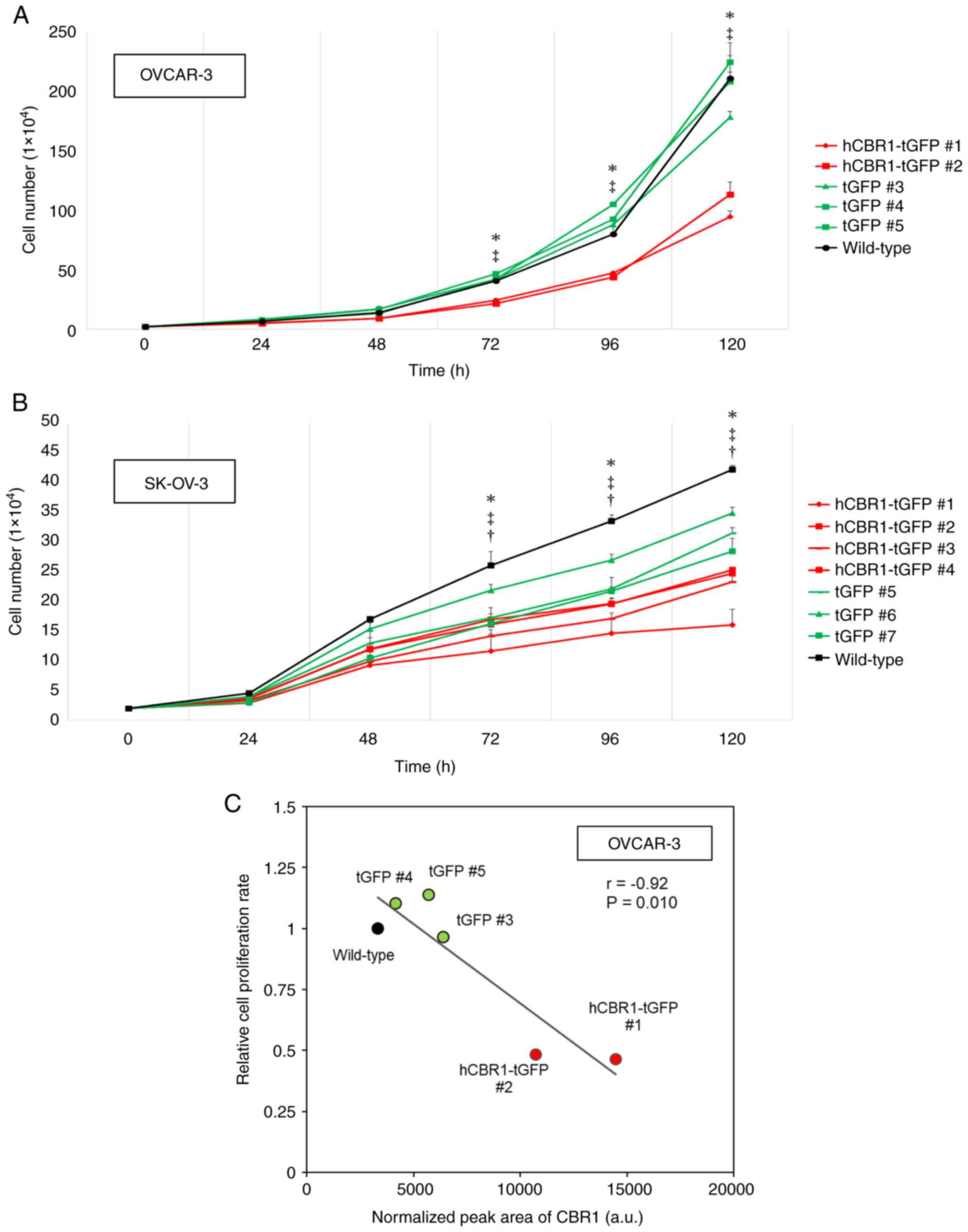

Antiproliferative effects of CBR1

To evaluate the effect of CBR1 overexpression on

tumor cell growth, we measured proliferation of OVCAR-3 and SK-OV-3

cells expressing hCBR1-tGFP. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, growth of OVCAR-3 and

SK-OV-3 cells expressing hCBR1-tGFP was slower than that of

wild-type or negative control cells. These results suggest that

overexpression of hCBR1 strongly inhibits growth of ovarian cancer

cells, although it should be noted that overexpression of tGFP

alone moderately affected growth of SK-OV-3 cells (Fig. 4B). hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing OVCAR-3

cells showed significant suppression of cell proliferation

(P<0.05, vs. negative control or wild-type) (Fig. 4A). hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing SK-OV-3

cells also showed significant suppression of cell proliferation

(P<0.05, vs. negative control or wild-type, Fig. 4B). As to SK-OV-3 cells, differences

in cellular growth were also observed between wild-type and

negative control cells (P<0.05, Fig.

4B). Because tGFP is potentially cytotoxic (21), expression of tGFP may also affect

the growth of SK-OV-3 cells.

| Figure 4.Inhibitory effects of CBR1 on growth

of ovarian cancer cells. (A and B) Proliferation of

hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing (A) OVCAR-3 and (B) SK-OV-3 cells. Cell

numbers were counted at each time point. *P<0.05, hCBR1-tGFP (#1

and #2) vs. tGFP (#3-#5) for OVCAR-3, or hCBR1-tGFP (#1-#4) vs.

tGFP (#5-#7) for SK-OV-3, ‡P<0.05, hCBR1-tGFP (#1 and #2) vs.

Wild-type for OVCAR-3, or hCBR1-tGFP (#1-#4) vs. Wild-type for

SK-OV-3, †P<0.05, tGFP (#5-#7) vs. Wild-type. (C) Correlation

between the normalized peak area of CBR1 measured in proteome

analysis and cell proliferation rate relative to wild-type. The X

and Y axes depict arbitrary values. The semi-quantitative amount of

CBR1 is shown as the sum of endogenous CBR1 expression and

exogenous hCBR1-tGFP expression. Cell proliferation rate was

represented as the number of cells increased per hour relative to

wild-type. a.u., arbitrary unit. CBR1, carbonyl reductase 1; hCBR1,

human CBR1; tGFP, turbo green fluorescent protein. |

In hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing OVCAR-3, we confirmed

an inverse correlation between hCBR1 overexpression and cell

proliferation (Fig. 4C). In the

hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing lines (#1, #2), CBR1 expression levels

were high, and the cell proliferation rate was reduced. By

contrast, negative control cells (#3-#5) and wild-type cells

expressed low levels of CBR1 and showed higher proliferation rates.

In these experiments, CBR1 expression is the sum of endogenous CBR1

and exogenous hCBR1-tGFP, and the higher levels of CBR1 protein in

hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing lines are consistent with the results

shown in Fig. 1B. Thus, these

results support the above data showing that

hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing lines grow more slowly than negative

control and wild-type cells (Fig.

4A). Previously, we showed that transient expression of CBR1 in

a xenograft mouse model may induce apoptosis through activation of

caspase pathways (6). Thus, stable

overexpression of hCBR1-tGFP may induce apoptosis in OVCAR-3 and

SK-OV-3 cells.

Altered intracellular signaling in

hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing cancer cell lines

To elucidate the CBR1-mediated molecular mechanism

underlying growth inhibition, we performed LC-MS/MS of OVCAR-3 cell

lysates, followed by IPA. Whole cell proteomics analysis using a

label-free quantification method plus MS resulted in quantification

of 939 proteins, with no samples showing outliers upon principal

component analysis (Fig. S1). Of

these, the abundance of 155 proteins correlated significantly with

expression of hCBR1 (FDR-adjusted P-value <0.05, Spearman's rank

correlation, Fig. S2). We then

performed IPA to identify enriched canonical pathways associated

with hCBR1-correlated proteins; the top 20 pathways are shown in

Table I. Expression of proteins

involved in various signaling pathways, whose role in controlling

tumor progression is suggested, correlated with expression of

hCBR1. Among these, the eIF2 signaling pathway was the most

enriched.

| Table I.Top 20 signaling pathways affected by

overexpression of CBR1 in OVCAR-3 cells. |

Table I.

Top 20 signaling pathways affected by

overexpression of CBR1 in OVCAR-3 cells.

| Ingenuity canonical

pathway | -log (P-value) | Ratio |

|---|

| eIF2 signaling | 20.3 | 0.103 |

| mTOR signaling | 6.77 | 0.052 |

| Regulation of eIF4

and p70S6K signaling | 6.50 | 0.056 |

| Coronavirus

pathogenesis pathway | 5.08 | 0.044 |

| Mitochondrial

dysfunction | 4.74 | 0.047 |

| CSDE1 signaling

pathway | 4.47 | 0.089 |

| Spliceosomal

cycle | 3.52 | 0.082 |

| Pentose phosphate

pathway (Oxidative Branch) | 3.37 | 0.400 |

| FAT10 signaling

pathway | 3.29 | 0.071 |

| Gluconeogenesis

I | 3.19 | 0.115 |

| Leukocyte

extravasation signaling | 2.75 | 0.031 |

| tRNA charging | 2.67 | 0.077 |

| Pentose phosphate

pathway | 2.64 | 0.182 |

| BAG2 signaling

pathway | 2.64 | 0.048 |

| Sirtuin signaling

pathway | 2.49 | 0.024 |

| VEGF signaling | 2.38 | 0.040 |

| Inhibition of

ARE-mediated mRNA degradation pathway | 2.37 | 0.031 |

| Virus entry via

endocytic pathways | 2.30 | 0.039 |

| Germ cell-sertoli

cell junction signaling | 2.26 | 0.029 |

| Oxidative

phosphorylation | 2.20 | 0.036 |

The z-score for the eIF2 signaling pathway, as

calculated by IPA, was +1.387. The z-score indicates whether the

detected signal is biased toward activation or inactivation, with

positive values indicating activation and negative values

indicating inactivation (Fig. S3).

Table I shows that eIF2 signaling

is highly affected by overexpression of hCBR1. Proteins associated

with eIF2 signaling are listed in Table II. Of the 23 proteins associated

with eIF2 signaling, 17 had positive correlation coefficients.

| Table II.Proteins associated with eIF2

signaling. |

Table II.

Proteins associated with eIF2

signaling.

| Gene symbol | UniProt ID | Protein name | Correlation

coefficient | -log10

(P-value) |

|---|

| EIF1AX | Q8BMJ3 | Eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 1A | 0.344 | 1.8 |

| EIF3F | Q9DCH4 | Eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 3 subunit F | 0.414 | 2.5 |

| PTBP1 | P17225 | Polypyrimidine

tract-binding protein 1 | −0.349 | 1.8 |

| RPL10 | Q6ZWV3 | 60S ribosomal

protein L10 | 0.399 | 2.3 |

| RPL11 | Q9CXW4 | 60S ribosomal

protein L11 | 0.404 | 2.4 |

| RPL13 | P47963 | 60S ribosomal

protein L13 | 0.328 | 1.6 |

| RPL14 | Q9CR57 | 60S ribosomal

protein L14 | −0.291 | 1.3 |

| RPL18A | P62717 | 60S ribosomal

protein L18a | 0.340 | 1.7 |

| RPL23 | P62830 | 60S ribosomal

protein L23 | 0.392 | 2.2 |

| RPL23A | P62751 | 60S ribosomal

protein L23a | 0.286 | 1.3 |

| RPL24 | Q8BP67 | 60S ribosomal

protein L24 | 0.418 | 2.5 |

| RPL27A | P14115 | 60S ribosomal

protein L27a | 0.337 | 1.7 |

| RPL31 | P62900 | 60S ribosomal

protein L31 | −0.315 | 1.5 |

| RPL34 | Q9D1R9 | 60S ribosomal

protein L34 | 0.497 | 3.5 |

| RPL7A | P12970 | 60S ribosomal

protein L7a | −0.465 | 3.1 |

| RPS10 | P63325 | 40S ribosomal

protein S10 | 0.320 | 1.6 |

| RPS12 | P63323 | 40S ribosomal

protein S12 | 0.422 | 2.6 |

| RPS15 | P62843 | 40S ribosomal

protein S15 | 0.324 | 1.6 |

| RPS15A | P62245 | 40S ribosomal

protein S15a | 0.285 | 1.3 |

| RPS25 | P62852 | 40S ribosomal

protein S25 | 0.333 | 1.7 |

| RPS29 | P62274 | 40S ribosomal

protein S29 | 0.392 | 2.2 |

| RPS9 | Q6ZWN5 | 40S ribosomal

protein S9 | −0.341 | 1.8 |

| RRAS2 | P62071 | Ras-related protein

R-Ras2 | −0.299 | 1.4 |

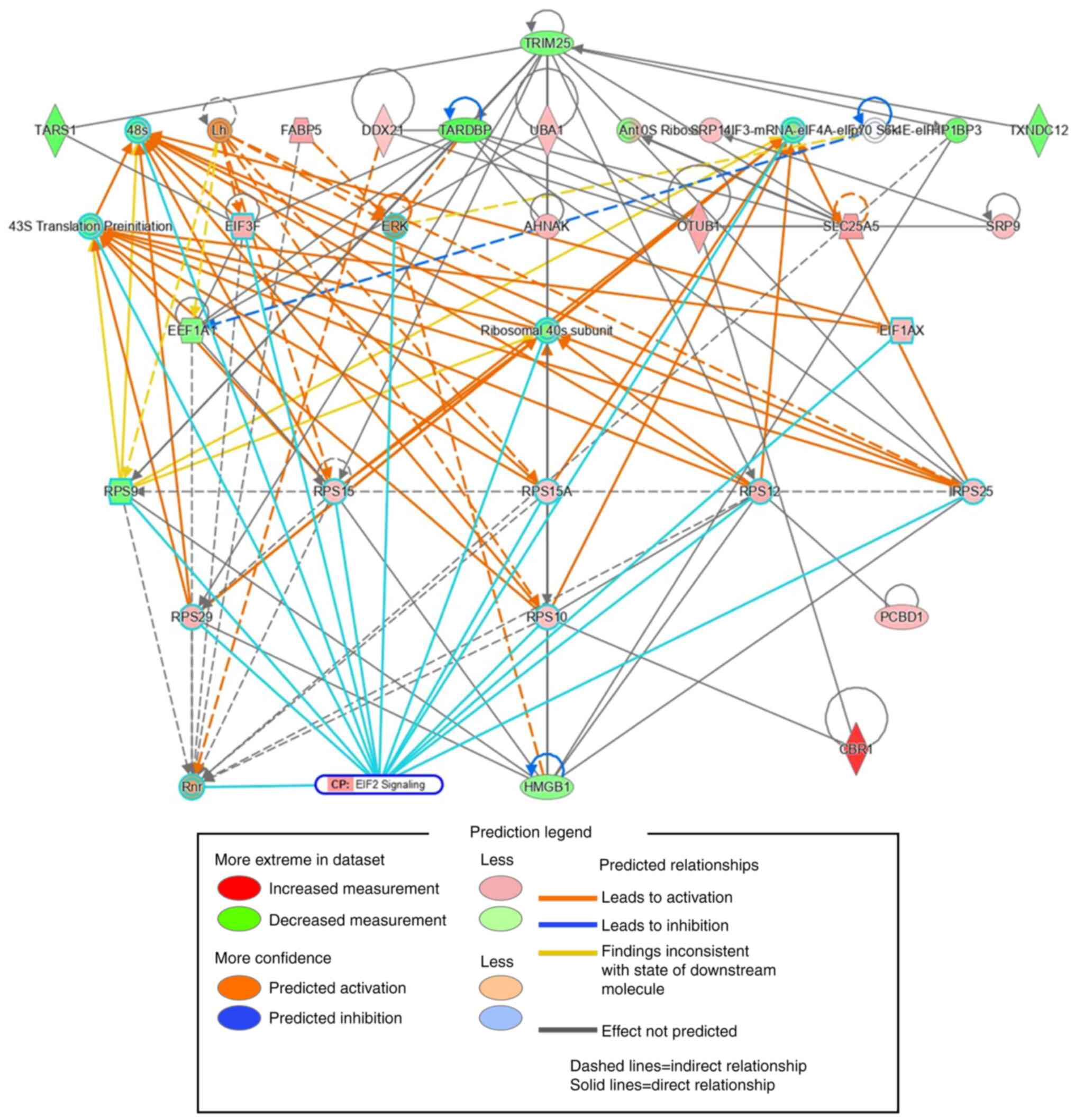

We also used IPA to perform a protein-protein

interaction network analysis of hCBR1-correlated proteins. The top

35 out of the 155 proteins whose expression correlated with that of

CBR1 were extracted in the order of interaction network robustness

and presented as a subnetwork (Fig.

5). Among the 35 proteins, 15 formed a subnetwork related to

eIF2 signaling, as shown by the cyan borders. These results suggest

that the eIF2 signaling pathway may be involved in suppressing cell

growth.

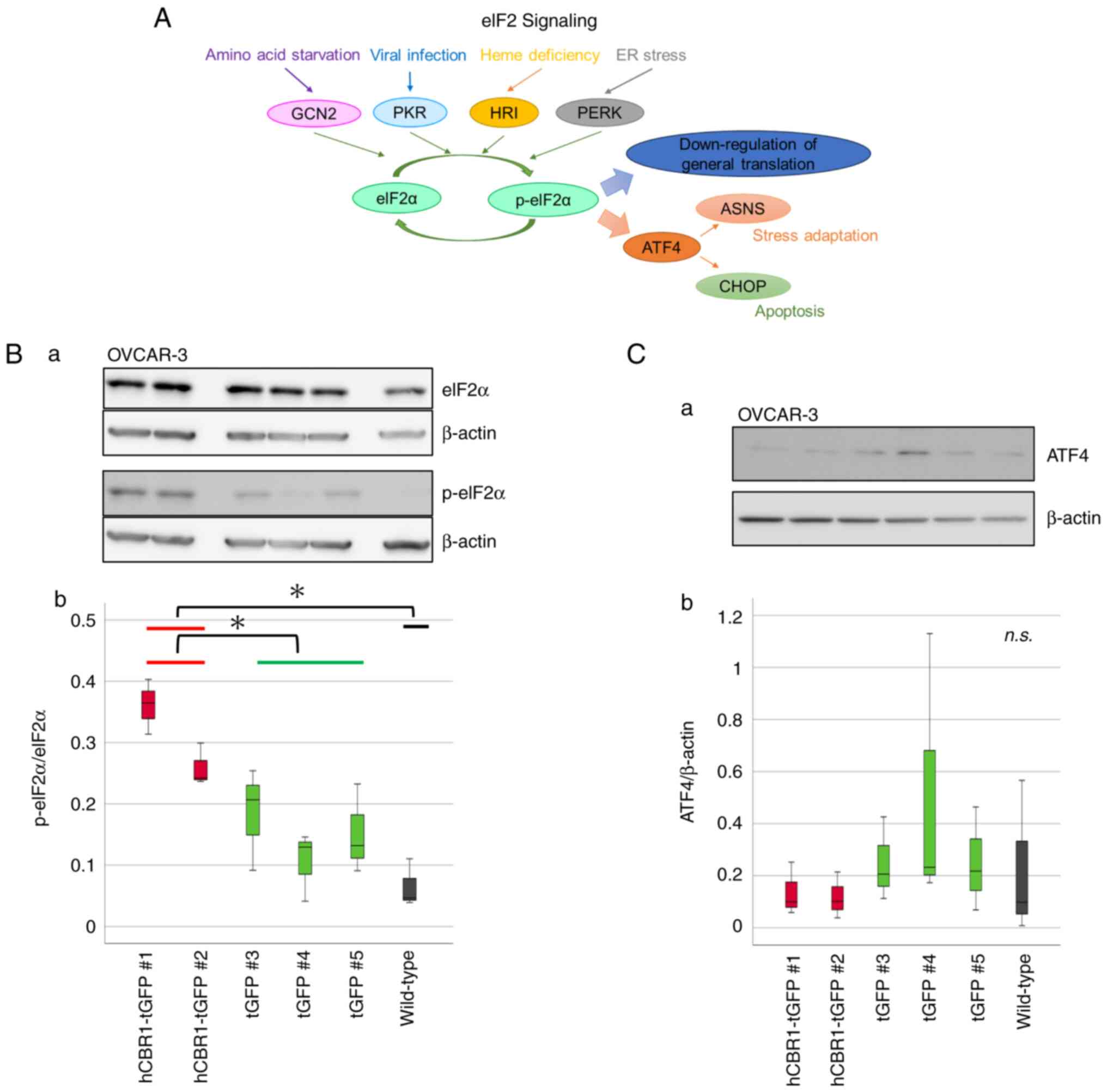

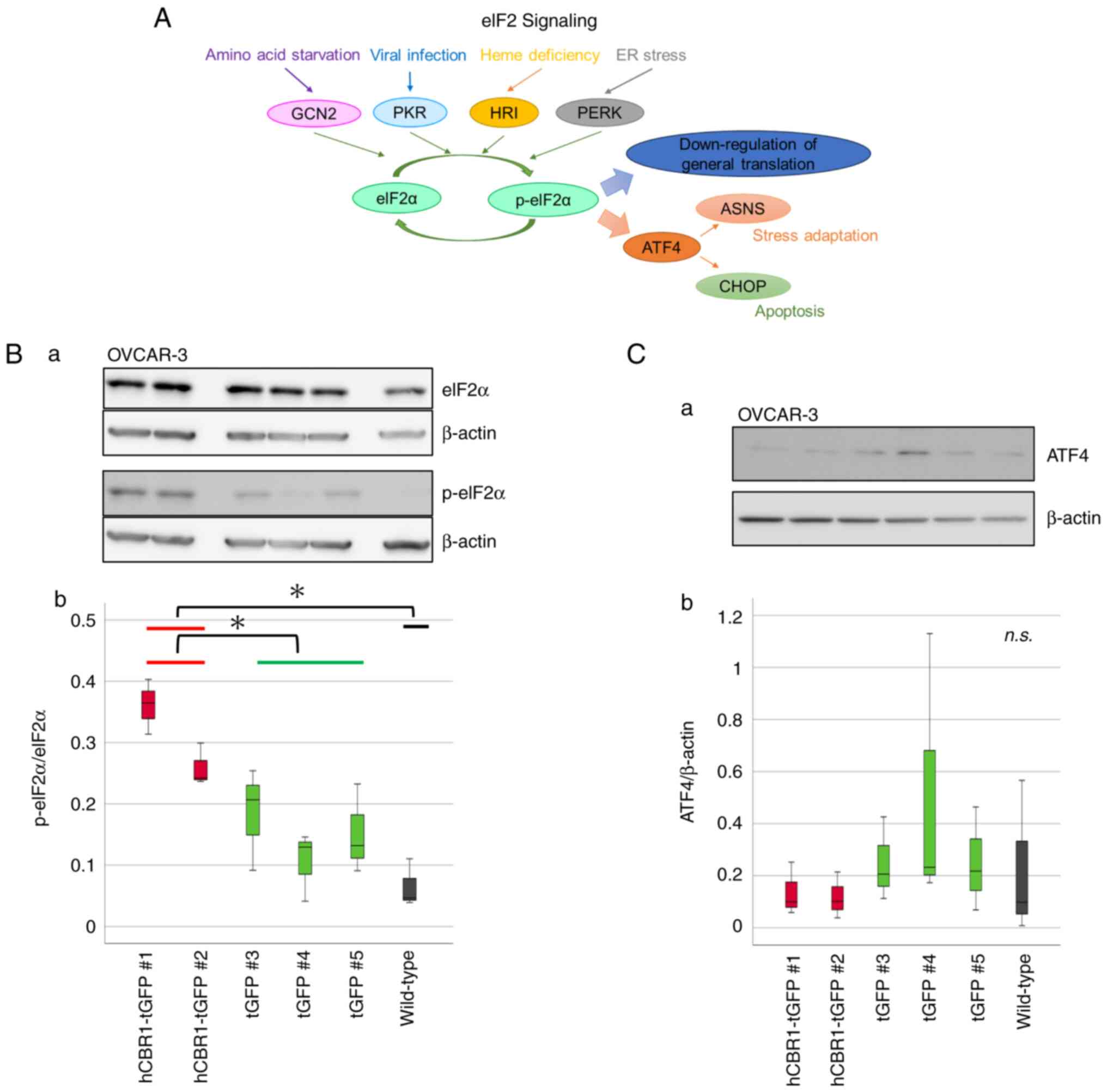

eIF2 phosphorylation status in OVCAR-3

cells stably expressing hCBR1-tGFP

Next, we investigated whether the eIF2 signaling

pathway is actually altered by overexpression of hCBR1-tGFP.

Considering the magnitude of changes in eIF2 signaling, and the

critical importance of phosphorylation status of eIF2 during

regulation of the pathway (Fig. 6A,

see also the Discussion section) (22), we performed immunoblot analysis to

examine phosphorylation of eIF2α, a subunit of eIF2. A clear band

corresponding to p-eIF2α was observed in lysates prepared from

hCBR1-tGFP-expressing cells (#1, #2) (Fig. 6B-a), confirming that overexpression

of hCBR1 induces phosphorylation of eIF2α. Expression and

phosphorylation of eIF2α protein in OVCAR-3 cells were quantified

using image analysis software. The results confirmed that the

phosphorylation levels of eIF2α in hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing cells

were higher than those in wild-type and negative control cells

(Fig. 6B-b).

| Figure 6.The eIF2 signaling pathway and

phosphorylation of eIF2α in hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing OVCAR-3

cells. (A) Schematic diagram of the eIF2 signaling pathway. Four

kinases of eIF2α have been identified in humans: GCN2, PKR, HRI,

and PERK. Phosphorylation of eIF2α leads to apoptosis and autophagy

via ASNS or CHOP. (B-a) Immunoblot analysis to detect

phosphorylation of the eIF2α protein. (B-b) The detected bands were

quantified using ImageJ. The ratio of the band intensity (i.e.,

p-eIF2α: eIF2α) is shown. *P<0.05. (C-a) Immunoblot analysis of

ATF-4 protein expression. (C-b) The ratio of the band intensity

(i.e., ATF-4: β-actin) is shown. n.s., not significant. Each

antibody reaction was performed on each membrane. eIF2, eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 2; hCBR1, human carbonyl reductase 1;

tGFP, turbo green fluorescent protein; GCN2, general control

nonderepressible-2; PKR, protein kinase R; HRI, heme-regulated

inhibitor; PERK, protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum

kinase; ASNS, aspartate synthetase; CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein;

p-eIF2, phosphorylated-eIF2; ATF-4, activating transcription factor

4. |

Phosphorylation of eIF2α downregulates general

translation and upregulates expression of ATF4 (Fig. 6A) (22). Although we examined involvement of

ATF4 downstream of eIF2α, we found that expression of ATF4 was not

upregulated in hCBR1-tGFP-expressing cells (Fig. 6C). Therefore, overexpression of

hCBR1 may induce downregulation of general translation via

phosphorylation of eIF2α.

Discussion

In this study, we generated ovarian cancer cells

stably expressing hCBR1-tGFP. Proliferation of

hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing cells was slower than that of negative

control and wild-type cells. To elucidate the mechanism of cell

growth suppression by CBR1 overexpression, we used proteomics

together with IPA. The results showed marked differences in the

expression of proteins involved in eIF2 signaling in

hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing cells. Concordantly, constitutive

phosphorylation of eIF2α, which plays a critical role in eIF2

signaling, suggests that CBR1 regulates cell growth via the eIF2

signaling pathway.

Generally, it is accepted that protein synthesis

drives the cell cycle (23). The

relationship between regulation of protein synthesis and cancer

cell growth has attracted considerable attention because regulation

of mRNA translation is a convergence point for many oncogenic

signals (24). The eIF2 signaling

pathway plays a central role in regulating general translation in

response to stress. eIF2 comprises three subunits: α, β, and γ.

GTP-bound eIF2 interacts with the initiating methionyl-tRNA

(ternary complex, TC) and transports it to the 40S ribosome

(25). The elF2 translation

initiation complex integrates a variety of stress-related signals

to downregulate general translation, but it upregulates translation

of specific mRNAs such as that encoding ATF4 (26). In this regard, because we did not

show upregulation of ATF4 protein, it may be that overexpression of

CBR1 downregulates general translation.

Phosphorylation of eIF2α is induced by a diverse

family of four stress-activated kinases: protein kinase R (PKR)

[induced by dsRNA], protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum

kinase (PERK) [induced by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress],

general control nonderepressible-2 (GCN2) [induced by amino acid

starvation], and heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI) [induced by heme

deficiency] (Fig. 6A). As a

limitation of this study, we could not confirm how CBR1 induces

phosphorylation of eIF2α. Therefore, it would be interesting to

examine this issue in future. We examined only one downstream eIF2α

pathway-related molecule (ATF4) in this study. Therefore, we would

like to examine the other downstream molecules and related

physiological changes, including oxidative stress-induced reactive

oxygen species generation, in a future study. On the other hand, in

addition to OVCAR-3, hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing SK-OV-3 cells were

established in this study. Although all hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing

cells showed hCBR1-tGFP expression, statistical significance was

not achieved as a group, which may also be a limitation of this

study.

Initiation of protein synthesis is regulated by two

rate-limiting steps: assembly of eukaryotic translation initiation

factor 4F (eIF4F) and formation of the TC. Assembly of eIF4F is

promoted by mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling

(27). It is interesting to note

that IPA revealed that within the proteome of

hCBR1-tGFP-overexpressing cells, factors involved in mTOR signaling

were among those whose levels changed (Table I), although it is unclear whether

mTOR signaling fluctuates upwards or downwards (Fig. S3). Since the eIF2 signaling pathway

and mTOR signaling are exquisitely coordinated to provide a robust

response to cellular stress (28–30),

overexpression of CBR1 may affect both pathways to suppress growth

of ovarian cancer cells.

In this study, we demonstrated regulation of the

eIF2 signaling pathway by CBR1. Although further studies are

needed, our data suggest a new therapeutic strategy for ovarian

cancer based on targeting CBR1 and related signaling cascades. This

could be achieved by developing molecularly targeted drugs directed

at components of the eIF2 signaling pathway, as well as CBR1

itself. In addition, CBR1 may be a potential biomarker of medical

prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Hodaka Fujii

(Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine), for helpful

discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. They also would

like to thank Ms. Miyu Miyazaki (Center for Scientific Equipment

Management, Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine), for

technical support with mass spectrometry.

Funding

This work was supported by a JSPS KAKENHI grant (grant no.

20K09589, to YY).

Availability of data and materials

The proteomics data generated in the present study

may be found in the Proteome Xchange and jPOST Repositor databases

under accession numbers PXD039299 and JPST001979, respectively or

at the following URLs: https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD039299

and https://repository.jpostdb.org/entry/JPST001979.2. The

other data generated in the present study may be requested from the

corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YK, MY and YY conceived the project. TF and YY

designed and supervised the project. YT performed LC-MS/MS

analysis. YK and MY performed the other experiments. YK, MY, TF and

YY wrote the manuscript. YK and MY confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CBR1

|

carbonyl reductase 1

|

|

hCBR1

|

human CBR1

|

|

eIF

|

eukaryotic translation initiation

factor

|

|

tGFP

|

turbo green fluorescent protein

|

|

LC-MS/MS

|

liquid chromatography followed by mass

spectrometry

|

|

p-eIF2

|

phosphorylated-eIF2

|

|

HRP

|

horseradish peroxidase

|

|

IPA

|

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

|

|

TC

|

ternary complex

|

|

PKR

|

protein kinase R

|

|

PERK

|

protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic

reticulum kinase

|

|

GCN2

|

general control nonderepressible-2

|

|

HRI

|

heme-regulated inhibitor

|

|

ATF4

|

activating transcription factor 4

|

|

mTOR

|

mechanistic target of rapamycin

|

|

Ab

|

antibody

|

References

|

1

|

Mindnich RD and Penning TM: Aldo-keto

reductase (AKR) superfamily: Genomics and annotation. Hum Genomics.

3:362–370. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Oksvold P,

Kampf C, Djureinovic D, Odeberg J, Habuka M, Tahmasebpoor S,

Danielsson A, Edlund K, et al: Analysis of the human

tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of

transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics.

13:397–406. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wermuth B, Bohren KM, Heinemann G, von

Wartburg JP and Gabbay KH: Human carbonyl reductase. Nucleotide

sequence analysis of a cDNA and amino acid sequence of the encoded

protein. J Biol Chem. 263:16185–16188. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Umemoto M, Yokoyama Y, Sato S, Tsuchida S,

Al-Mulla F and Saito Y: Carbonyl reductase as a significant

predictor of survival and lymph node metastasis in epithelial

ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 85:1032–1036. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Osawa Y, Yokoyama Y, Shigeto T, Futagami M

and Mizunuma H: Decreased expression of carbonyl reductase 1

promotes ovarian cancer growth and proliferation. Int J Oncol.

46:1252–1258. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Miura R, Yokoyama Y, Shigeto T, Futagami M

and Mizunuma H: Inhibitory effect of carbonyl reductase 1 on

ovarian cancer growth via tumor necrosis factor receptor signaling.

Int J Oncol. 47:2173–2180. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Nishimoto Y, Murakami A, Sato S, Kajimura

T, Nakashima K, Yakabe K, Sueoka K and Sugino N: Decreased carbonyl

reductase 1 expression promotes tumor growth via epithelial

mesenchymal transition in uterine cervical squamous cell

carcinomas. Reprod Med Biol. 17:173–181. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kajimura T, Sato S, Murakami A,

Hayashi-Okada M, Nakashima K, Sueoka K and Sugino N: Overexpression

of carbonyl reductase 1 inhibits malignant behaviors and epithelial

mesenchymal transition by suppressing TGF-β signaling in uterine

leiomyosarcoma cells. Oncol Lett. 18:1503–1512. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Takenaka K, Ogawa E, Oyanagi H, Wada H and

Tanaka F: Carbonyl reductase expression and its clinical

significance in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol

Biomarkers Prev. 14:1972–1975. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Graves PR and Haystead TA: Molecular

biologist's guide to proteomics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 66:39–63.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chandramouli K and Qian PY: Proteomics:

Challenges, techniques and possibilities to overcome biological

sample complexity. Hum Genomics Proteomics. 8:2392042009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang D, Eraslan B, Wieland T, Hallström B,

Hopf T, Zolg DP, Zecha J, Asplund A, Li LH, Meng C, et al: A deep

proteome and transcriptome abundance atlas of 29 healthy human

tissues. Mol Syst Biol. 15:e85032019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Martínez-Rodríguez F, Limones-González JE,

Mendoza-Almanza B, Esparza-Ibarra EL, Gallegos-Flores PI,

Ayala-Luján JL, Godina-González S, Salinas E and Mendoza-Almanza G:

Understanding cervical cancer through proteomics. Cells.

10:18542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shigeto T, Yokoyama Y, Xin B and Mizunuma

H: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α and γ ligands

inhibit the growth of human ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 18:833–840.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wakui M, Yokoyama Y, Wang H, Shigeto T,

Futagami M and Mizunuma H: Efficacy of a methyl ester of

5-aminolevulinic acid in photodynamic therapy for ovarian cancers.

J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 136:1143–1150. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cebulla J, Huuse EM, Pettersen K, van der

Veen A, Kim E, Andersen S, Prestvik WS, Bofin AM, Pathak AP,

Bjørkøy G, et al: MRI reveals the in vivo cellular and vascular

response to BEZ235 in ovarian cancer xenografts with different

PI3-kinase pathway activity. Br J Cancer. 112:504–513. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zalewski M, Kulbacka J, Saczko J,

Drag-Zalesinska M and Choromanska A: Valspodar-modulated

chemotherapy in human ovarian cancer cells SK-OV-3 and MDAH-2774.

Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 19:234–241. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lu T, Tang J, Shrestha B, Heath BR, Hong

L, Lei YL, Ljungman M and Neamati N: Up-regulation of

hypoxia-inducible factor antisense as a novel approach to treat

ovarian cancer. Theranostics. 10:6959–6976. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ohgane K and Yoshioka H: Quantification of

gel bands by an image J Macro, Band/Peak Quantification Tool v1.

Protocols.io. 2019.doi:/10.17504/protocols.io.7vghn3w.

|

|

20

|

Yokoyama M, Fujita T, Kadonosawa Y, Tatara

Y, Motooka D, Ikawa M, Fujii H and Yokoayama Y: Development of

transgenic mice overexpressing mouse carbonyl reductase 1. Mol Biol

Rep. 50:531–540. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Costantini LM, Fossati M, Francolini M and

Snapp EL: Assessing the tendency of fluorescent proteins to

oligomerize under physiologic conditions. Traffic. 13:643–649.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Boye E and Grallert B: eIF2α

phosphorylation and the regulation of translation. Curr Genet.

66:293–297. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Johnston GC, Pringle JR and Hartwell LH:

Coordination of growth with cell division in the yeast

Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Exp Cell Res. 105:79–98. 1977. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kovalski JR, Kuzuoglu-Ozturk D and Ruggero

D: Protein synthesis control in cancer: selectivity and therapeutic

targeting. EMBO J. 41:e1098232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Clemens MJ and Bommer UA: Translational

control: The cancer connection. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 31:1–23.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Hinnebusch AG: Molecular mechanism of

scanning and start codon selection in eukaryotes. Microbiol Mol

Biol Rev. 75:434–467. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Harris AL: Hypoxia-a key regulatory factor

in tumour growth. Nat Rev Cancer. 2:38–47. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hinnebusch AG: The scanning mechanism of

eukaryotic translation initiation. Annu Rev Biochem. 83:779–812.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gandin V, Masvidal L, Cargnello M, Gyenis

L, McLaughlan S, Cai Y, Tenkerian C, Morita M, Balanathan P,

Jean-Jean O, et al: mTORC1 and CK2 coordinate ternary and eIF4F

complex assembly. Nat Commun. 7:111272016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wengrod J, Wang D, Weiss S, Zhong H, Osman

I and Gardner LB: Phosphorylation of eIF2α triggered by mTORC1

inhibition and PP6C activation is required for autophagy and is

aberrant in PP6C-mutated melanoma. Sci Signal. 8:ra272015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|