Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) commonly occurs in

postmenopausal women and accounts for more than two-thirds of

gynaecological cancer-related mortalities (1–3). In

2020, a total of 313,959 new cases and 207,252 mortalities due to

OC were recorded worldwide (4).

Cytoreductive surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy is

the standard treatment strategy for patients with OC (5,6).

Notably, 70.0–80.0% of patients with OC suffer from disease

recurrence and the majority of these patients will eventually

develop platinum resistance through multiple recurrences (7–10).

Currently, platinum resistance is a noteworthy obstacle that

negatively affects the survival of patients with OC (11).

Previously, studies report that antiangiogenic

therapy can inhibit neovascularisation and the supply of nutrients

and oxygen to cancer cells, thus suppressing tumour proliferation,

invasion and metastasis (12,13).

Emerging evidence also suggests that antiangiogenic therapy, such

as bevacizumab and apatinib, plus chemotherapy is a promising

treatment approach for patients with platinum-resistant recurrent

OC (PRROC) (14–16). For example, the randomised clinical

trial APPROVE indicates that apatinib plus pegylated liposomal

doxorubicin (PLD) increases progression-free survival (PFS) with

tolerable adverse effects compared with PLD alone in patients with

PRROC (14). Another study

demonstrates that bevacizumab plus chemotherapy (PLD,

weekly-paclitaxel or topotecan) increases the objective response

rate (ORR) and PFS, but does not increase overall survival (OS)

when compared with chemotherapy alone in patients with PRROC

(15). Additionally, a study

reveals that apatinib plus paclitaxel increases PFS and OS with

acceptable toxicity compared with paclitaxel monotherapy in the

same patients (16). Notably, the

aforementioned studies include patients with PRROC who are only

treated with one type of antiangiogenic drug, either apatinib or

bevacizumab, plus chemotherapy. Therefore, evaluating the efficacy

and safety of the different antiangiogenic drugs (bevacizumab or

apatinib) plus chemotherapy could provide further clinical evidence

for the application of this treatment modality.

The present study aimed to investigate the efficacy

and safety profile of antiangiogenic therapy (bevacizumab or

apatinib) plus chemotherapy in patients with PRROC.

Materials and methods

Patients

In the present retrospective study, a total of 86

female patients with PRROC that received antiangiogenic therapy

plus chemotherapy between July 2019 and May 2023 at the People's

Hospital of Zhongshan City (Zhongshan, China) were selected.

Patient data from the hospital records were accessed from April 19,

2024 to April 29, 2024. The present study obtained permission from

the Ethics Committee of People's Hospital of Zhongshan City

(approval no. 2024-033; Zhongshan, China). The patients signed the

informed consent form, or, if the patients were unable to sign,

their family members signed it on their behalf.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients

diagnosed with epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal or fallopian

tube cancer (17); ii) aged ≥18

years; iii) treated with antiangiogenic therapy plus chemotherapy;

iv) patients with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)

performance status (PS) score of ≤2; v) experienced disease

progression within 6 months after receiving platinum-based

chemotherapy; and vi) displayed at least one assessable lesion

according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

(RECIST) version 1.1 (18).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients

with uncontrolled hypertension; ii) patients with coagulation

disorders; iii) patients with a history of bleeding; iv) patients

with gastrointestinal perforation; and v) patients with no

available follow-up data.

Treatment

Treatment data from patients with PRROC were

collected from the electronic medical system. The treatment

regimens were provided according to the National Comprehensive

Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline and the condition and requests of

the patient (19). The

antiangiogenic drugs used were bevacizumab (10 mg/kg once every 2

weeks) or apatinib (250 mg once every day). The chemotherapy drugs

were PLD (40 mg/m2 once every 4 weeks), paclitaxel (80

mg/m2 once every week) or gemcitabine (1,000

mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks). The dose of each

drug was prescribed as recommended based on the NCCN guideline and

was adjusted based on the condition of the patient (19). Every cycle was defined as 4 weeks of

treatment with the aforementioned drugs.

Follow-up and assessment data

Follow-up data from patients with PRROC were

obtained from the electronic medical system. Patients were followed

up every two cycles of therapy and their condition was evaluated

using magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography (20). The median duration of follow-up was

13.7 months and the final follow-up date was August 2023. The

treatment response of patients with PRROC was assessed based on

RECIST version 1.1 and the best response was selected for

evaluation. ORR and disease control rate (DCR) were also measured.

PFS and OS were determined based on the follow-up data.

Additionally, the adverse events were retrieved from the medical

records of patients with PRROC.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

version 24.0 software (IBM Corp). For sample size calculation, an

ORR of 0.3 and a confidence interval width of 0.2 was assumed.

Assuming a dropout rate of 5%, the minimum sample size required was

86. The characteristics, treatment response and adverse events of

patients with PRROC were assessed using descriptive statistics. The

association between the current treatments, antiangiogenic drugs

and chemotherapy drugs with PFS and OS was examined using

Kaplan-Meier curves. All data were analysed using a log-rank test.

Univariate and multivariate (stepwise forward) Cox regression

analyses were performed to determine the factors that affect PFS

and OS. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Baseline features of patients with

PRROC

In the present study, the median age of patients

with PRROC was 60.5 years [interquartile range (IQR), 51.0–67.0

years). A total of 32 (37.2%) patients presented with ascites.

Moreover, 53 (61.6%) patients received antiangiogenic therapy plus

chemotherapy as a second-line treatment and the remaining 33

(38.4%) patients received antiangiogenic therapy plus chemotherapy

as a third-line or above treatment. Regarding the antiangiogenic

drugs, 68 (79.1%) patients were treated with bevacizumab and 18

(20.9%) patients received apatinib. Finally, in terms of

chemotherapy, 51 (59.3%) patients received PLD, 21 (24.4%) received

weekly-paclitaxel and 14 (16.3%) received gemcitabine. The detailed

data of patients with PRROC are presented in Table I.

| Table I.Characteristics of patients with

PRROC. |

Table I.

Characteristics of patients with

PRROC.

| Characteristics | Patients with PRROC

(n=86) |

|---|

| Age, years [median

(IQR)] | 60.5 (51.0–67.0) |

| Age, n (%) |

|

| <65

years | 57 (66.3) |

| ≥65

years | 29 (33.7) |

| Origin of cancer, n

(%) |

|

|

Ovary | 77 (89.5) |

| Fallopian

tube | 6 (7.0) |

|

Peritoneum | 3 (3.5) |

| Histology subtype, n

(%) |

|

| HGSC | 66 (76.7) |

| LGSC | 3 (3.5) |

|

Endometrioid carcinoma | 8 (9.3) |

| Clear

cell carcinoma | 9 (10.5) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) |

|

| 0 | 33 (38.3) |

| 1 | 47 (54.7) |

| 2 | 6 (7.0) |

| FIGO stage, n

(%) |

|

| I | 4 (4.7) |

| II | 7 (8.1) |

| III | 64 (74.4) |

| IV | 11 (12.8) |

| Platinum-free

interval ≤3 months, n (%) | 27 (31.4) |

| Ascites, n (%) | 32 (37.2) |

| CA-125 ≥100 U/ml, n

(%) | 61 (70.9) |

| Prior chemotherapy,

n (%) | 86 (100.0) |

| Prior

antiangiogenic therapy, n (%) | 9 (10.5) |

| Current treatment

lines, n (%) |

|

|

Second | 53 (61.6) |

| Third

or above | 33 (38.4) |

| Antiangiogenic

drugs, n (%) |

|

|

Bevacizumab | 68 (79.1) |

|

Apatinib | 18 (20.9) |

| Chemotherapy drugs,

n (%) |

|

|

PLD | 51 (59.3) |

|

Weekly-paclitaxel | 21 (24.4) |

|

Gemcitabine | 14 (16.3) |

Best response, ORR and DCR in patients

with PRROC

In terms of the treatment response of patients with

PRROC that received antiangiogenic therapy plus chemotherapy, no

(0.0%) patients achieved a complete response (CR) and 29 (33.7%)

patients achieved a partial response (PR). Furthermore, the ORR and

DCR of patients with PRROC were 33.7 and 77.9%, respectively

(Table II).

| Table II.Treatment response of patients with

PRROC. |

Table II.

Treatment response of patients with

PRROC.

| Treatment

response | Patients with PRROC

(n=86) |

|---|

| Best response, n

(%) |

|

| CR | 0 (0.0) |

| PR | 29 (33.7) |

| SD | 38 (44.2) |

| PD | 19 (22.1) |

| ORR, n (%) |

|

|

Yes | 29 (33.7) |

| No | 57 (66.3) |

| DCR, n (%) |

|

|

Yes | 67 (77.9) |

| No | 19 (22.1) |

PFS and OS in patients with PRROC with

different treatment information

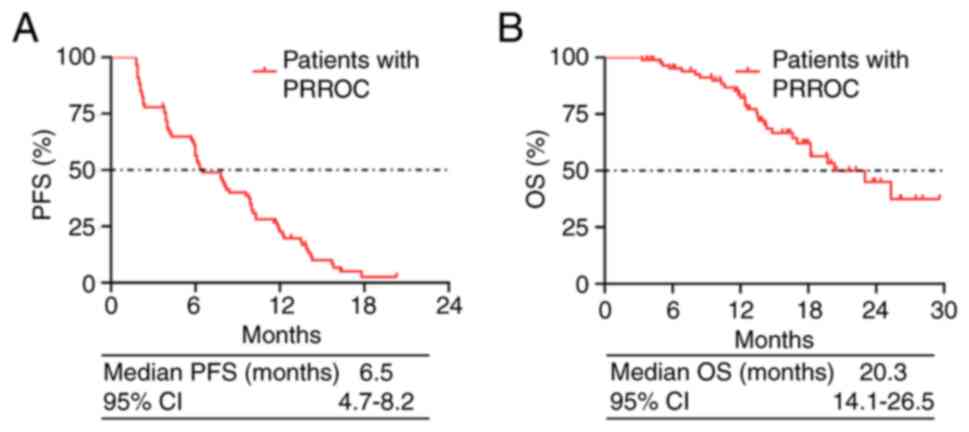

Results of the present study revealed that the

overall median PFS in patients with PRROC was 6.5 months [95%

confidence interval (CI), 4.7–8.2 months; Fig. 1A]. The overall median OS was 20.3

months (95% CI, 14.1–26.5 months; Fig.

1B).

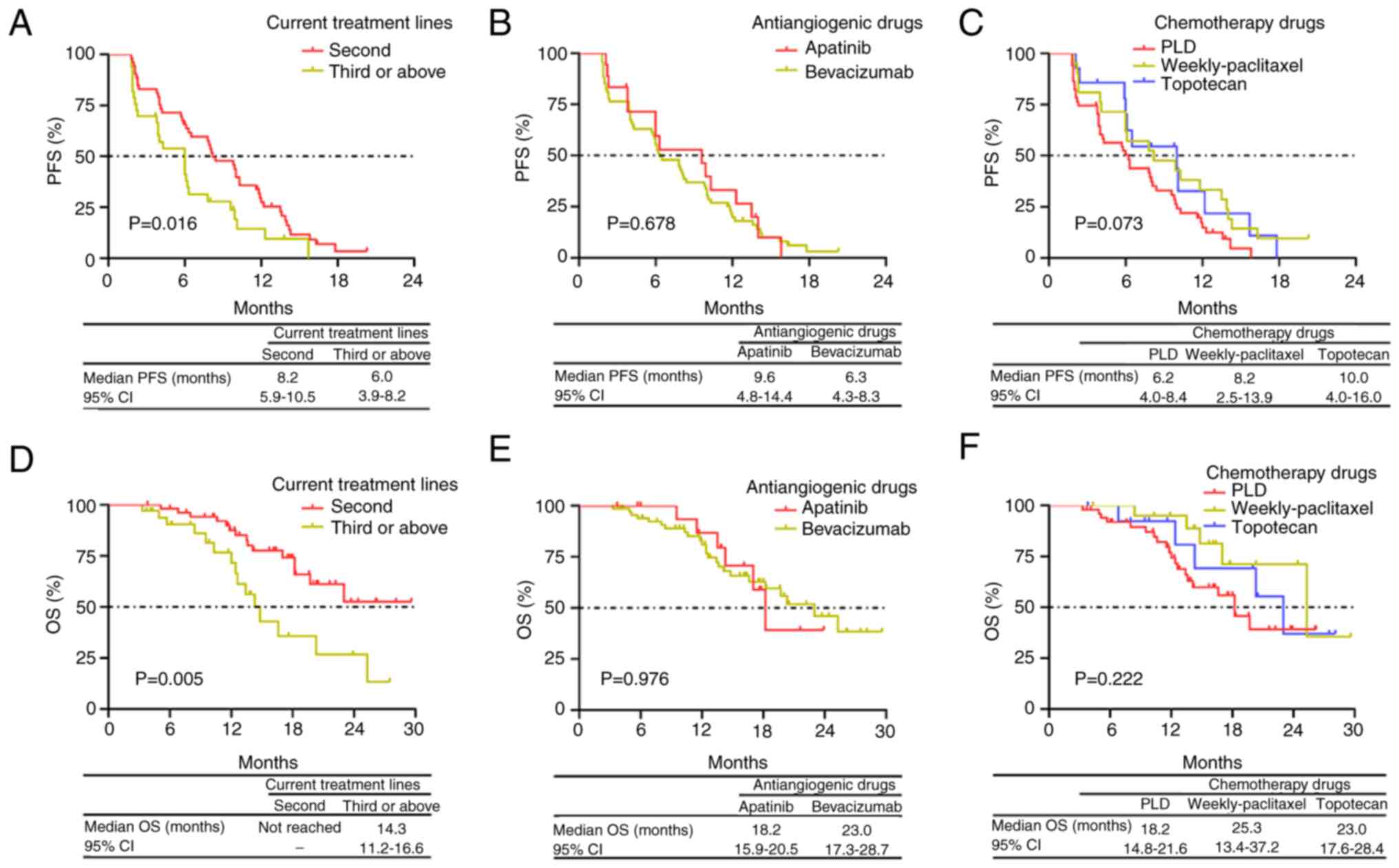

PFS was prolonged in patients with PRROC who

received antiangiogenic therapy plus chemotherapy as a second-line

treatment compared with patients who received the aforementioned

regimen as a third-line or above treatment (P=0.016; Fig. 2A). However, no significant

difference in PFS between patients with PRROC who received

bevacizumab and patients who received apatinib was observed

(P=0.678; Fig. 2B). Additionally,

no significant difference in PFS was observed between patients who

were treated with PLD, weekly-paclitaxel or gemcitabine (P=0.073;

Fig. 2C).

OS was also increased in patients with PRROC who

received antiangiogenic therapy plus chemotherapy as a second-line

treatment vs. patients who received it as a third-line or above

treatment (P=0.005; Fig. 2D). OS

did not significantly differ between patients who received

bevacizumab and patients who received apatinib (P=0.976; Fig. 2E). Additionally, no significant

difference in OS was observed between patients with PRROC who were

treated with PLD, weekly-paclitaxel or gemcitabine (P=0.222;

Fig. 2F).

Independent factors associated with

PFS in patients with PRROC

Stepwise forward multivariate Cox regression model

analysis revealed that ascites (yes vs. no) [hazard ratio

(HR)=1.804; P=0.018] and current treatment lines (third or above

vs. second) (HR=1.921; P=0.010) were independently associated with

a reduced PFS in patients with PRROC (Table III).

| Table III.Univariate and stepwise forward

multivariate COX regression models of PFS. |

Table III.

Univariate and stepwise forward

multivariate COX regression models of PFS.

| A, Univariate COX

regression model |

|---|

|

|---|

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, ≥65 years vs.

<65 years | 1.371

(0.841–2.234) | 0.205 |

| Origin of

cancer |

|

|

|

Ovary | Reference |

|

|

Fallopian tube | 1.401

(0.601–3.265) | 0.435 |

|

Peritoneum | 1.078

(0.337–3.451) | 0.899 |

| Histology

subtype |

|

|

|

HGSC | Reference |

|

|

LGSC | 0.322

(0.045–2.335) | 0.263 |

|

Endometrioid carcinoma | 0.519

(0.223–1.207) | 0.128 |

| Clear

cell carcinoma | 0.684

(0.326–1.438) | 0.317 |

| ECOG PS | 1.459

(0.997–2.135) | 0.052 |

| FIGO stage | 1.592

(1.071–2.366) | 0.021 |

| Platinum-free

interval, >3 months vs. ≤3 months | 1.126

(0.686–1.847) | 0.639 |

| Ascites, yes vs.

no | 1.671

(1.033–2.702) | 0.036 |

| CA-125, ≥100 U/ml

vs. <100 U/ml | 0.945

(0.569–1.571) | 0.828 |

| Prior

antiangiogenic therapy, yes vs. no | 1.685

(0.801–3.542) | 0.169 |

| Current treatment

lines, third or above vs. second | 1.788

(1.100–2.905) | 0.019 |

| Antiangiogenic

drugs, bevacizumab vs. apatinib | 1.127

(0.638–1.991) | 0.681 |

| Chemotherapy

drugs |

|

|

|

PLD | Reference |

|

|

Weekly-paclitaxel | 0.569

(0.325–0.995) | 0.048 |

|

Gemcitabine | 0.585

(0.298–1.147) | 0.119 |

|

| B, Stepwise

forward multivariate COX regression model |

|

| Ascites, yes vs.

no | 1.804

(1.106–2.942) | 0.018 |

| Current treatment

lines, third or above vs. second | 1.921

(1.172–3.150) | 0.010 |

Independent factors associated with OS

in patients with PRROC

Stepwise forward multivariate Cox regression model

analysis indicated that ascites (yes vs. no) (HR=2.439; P=0.026)

and current treatment lines (third or above vs. second) (HR=2.991;

P=0.003) were independently associated with a reduced OS in

patients with PRROC (Table

IV).

| Table IV.Univariate and stepwise forward

multivariate COX regression models of OS. |

Table IV.

Univariate and stepwise forward

multivariate COX regression models of OS.

| A, Univariate COX

regression model |

|---|

|

|---|

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, ≥65 years vs.

<65 years | 2.078

(1.012–4.267) | 0.046 |

| Origin of

cancer |

|

|

|

Ovary | Reference |

|

|

Fallopian tube | 0.886

(0.209–3.750) | 0.869 |

|

Peritoneum | 1.744

(0.411–7.403) | 0.451 |

| Histology

subtype |

|

|

|

HGSC | Reference |

|

|

LGSC | 1.949

(0.252–15.097) | 0.523 |

|

Endometrioid carcinoma | 0.220

(0.030–1.630) | 0.138 |

| Clear

cell carcinoma | 0.539

(0.162–1.794) | 0.314 |

| ECOG PS | 1.475

(0.832–2.614) | 0.183 |

| FIGO stage | 2.031

(1.016–4.063) | 0.045 |

| Platinum-free

interval, >3 months vs. ≤3 months | 1.363

(0.647–2.875) | 0.415 |

| Ascites, yes vs.

no | 2.133

(0.999–4.552) | 0.050 |

| CA-125, ≥100 U/ml

vs. <100 U/ml | 1.726

(0.704–4.231) | 0.233 |

| Prior

antiangiogenic therapy, yes vs. no | 2.185

(0.742–6.436) | 0.156 |

| Current treatment

lines, third or above vs. second | 2.729

(1.325–5.621) | 0.006 |

| Antiangiogenic

drugs, bevacizumab vs. apatinib | 1.014

(0.411–2.504) | 0.976 |

| Chemotherapy

drugs |

|

|

|

PLD | Reference |

|

|

Weekly-paclitaxel | 0.443

(0.166–1.185) | 0.105 |

|

Gemcitabine | 0.665

(0.246–1.793) | 0.420 |

|

| B, Stepwise

forward multivariate COX regression model |

|

| Ascites, yes vs.

no | 2.439

(1.115–5.333) | 0.026 |

| Current treatment

lines, third or above vs. second | 2.991

(1.436–6.232) | 0.003 |

Adverse events in patients with

PRROC

In the present cohort, the most common adverse

events in patients with PRROC were leukopenia (34.9%), hypertension

(30.2%), fatigue (30.2%), neutropenia (29.1%) as well as nausea and

vomiting (27.9%). The specific adverse events are presented in

Table V.

| Table V.Adverse events of patients with PRROC

(n=86). |

Table V.

Adverse events of patients with PRROC

(n=86).

| Adverse events | Patients with

PRROC, n (%) |

|---|

| Leukopenia | 30 (34.9) |

| Hypertension | 26 (30.2) |

| Fatigue | 26 (30.2) |

| Neutropenia | 25 (29.1) |

| Nausea and

vomiting | 24 (27.9) |

| Anaemia | 21 (24.4) |

| Hand-foot

syndrome | 17 (19.8) |

| Diarrhoea | 14 (16.3) |

| Dysregulated liver

function | 14 (16.3) |

| Oral ulcer | 14 (16.3) |

|

Thrombocytopenia | 13 (15.1) |

| Proteinuria | 10 (11.6) |

| Bleeding | 5 (5.8) |

| Gastrointestinal

perforation | 2 (2.3) |

Discussion

Platinum-based chemotherapy is the mainstay of OC

treatment, but the occurrence of platinum resistance remains a

challenge (9,10). Currently, single-agent non-platinum

chemotherapy is one of the most commonly used treatment approaches

for patients with PRROC (21). The

efficacy of single-agent non-platinum chemotherapy in patients with

PRROC has been investigated previously (14,22).

For example, a previous study reveals that the median PFS and OS in

patients with PRROC who received weekly-paclitaxel are 6.1 and 10.4

months, respectively (22). Another

study demonstrates that patients with PRROC who are treated with

PLD yield an ORR and DCR of 10.9 and 53.1%, respectively, with a

median PFS and OS of 3.3 and 14.4 months, respectively (14). In the present study, the ORR and DCR

of patients with PRROC who received antiangiogenic therapy plus

chemotherapy were 33.7 and 77.9%, respectively, with a PFS of 6.5

months and an OS of 20.3 months. The aforementioned values were all

increased compared with those reported in previous studies

(14,22). A possible reason for this

discrepancy might be that patients with PRROC in the present study

received antiangiogenic therapy in addition to single-agent

non-platinum chemotherapy, while the previous aforementioned

studies only use single-agent non-platinum chemotherapy.

Antiangiogenic drugs inhibit the vascular endothelial growth factor

signalling pathway, which subsequently inhibits the delivery of

nutrients and oxygen to tumour cells, suppressing tumour growth and

metastasis (12,13). Additionally, antiangiogenic drugs

normalise the abnormal tumour vasculature, increasing vascular

perfusion and promoting the infiltration of immune effector cells

into tumours, which may promote anticancer immunity (23). Previous studies also report that

antiangiogenic drugs have synergistic effects with chemotherapy in

killing tumour cells (24–27). In addition, a number of previous

studies reveal that patients with PRROC who receive antiangiogenic

therapy plus chemotherapy have ORRs and DCRs ranging from 27.3–43.1

and 57.1–84.4%, respectively. Furthermore, in these previous

studies, the median PFS and OS range from 5.0–7.1 and 16.6–23.0

months, respectively (14–16,28,29).

Therefore, the results of the present study were similar to those

of the aforementioned studies, which suggested that the results of

the present study were valid (14–16,28,29).

Notably, the advantage of the present study was that it included

patients with PRROC who received different antiangiogenic drugs

(bevacizumab or apatinib) plus chemotherapy, while previous studies

only included one type of antiangiogenic drug. The results of the

present study may provide further comprehensive evidence for the

application of antiangiogenic drugs plus chemotherapy in patients

with PRROC.

The present study demonstrated that administering

antiangiogenic therapy plus chemotherapy as a third-line or above

therapy was independently associated with a reduced PFS and OS in

patients with PRROC compared with patients who received the therapy

as a second-line treatment. A possible explanation for this may be

that patients with PRROC are administered antiangiogenic drugs plus

chemotherapy as a third-line or above therapy after their first-

and second-line treatments fail; thus, these patients may be more

resistant to multiple types of chemotherapy drugs compared with

those who received the therapy as a second-line treatment.

Additionally, in patients with PRROC who received antiangiogenic

therapy plus chemotherapy, ascites also independently predicted

reduced PFS and OS values compared with patients that did not have

ascites. This may be explained as the ascites themselves represent

the metastasis of malignant cells into the peritoneal cavity and

thus indicate the aggravated progression of the tumour (30).

The safety of antiangiogenic therapy plus

chemotherapy in treating patients with PRROC is also a noteworthy

issue (31,32). A previous study discloses that the

most common adverse events in patients with PRROC who receive

apatinib plus PLD are decreased white blood cell count (60.8%),

decreased neutrophil count (59.5%) and oral ulcers (28.4%)

(14). Another study demonstrates

that the most common adverse events in patients with PRROC who were

treated with bevacizumab plus PLD are mucositis (including

dysphagia; 64.0%), palmar-plantar erythroderma/ulceration (52.0%)

and asthenia (52.0%) (33). In the

present study, the most frequent adverse events were leukopenia

(34.9%), hypertension (30.2%) and fatigue (30.2%). The incidences

of the aforementioned adverse events were reduced compared with

those reported in previous studies, which could be attributed to

the underestimation of adverse events due to the retrospective

nature of the present study. Moreover, only previously reported

adverse events were observed. The findings of the present study

support the safety of antiangiogenic therapy plus chemotherapy in

patients with PRROC.

However, the present study had limitations. Firstly,

the sample size in the present study was small. Therefore, studies

with a larger sample size are required to verify the results of the

present study. Secondly, the present study was a single-arm study;

therefore, the results should be further verified by randomised,

controlled studies. Finally, the follow-up period of the present

study was short. Therefore, further studies with a longer follow-up

period should be carried out to investigate the efficacy and safety

of antiangiogenic therapy plus chemotherapy in patients with

PRROC.

In conclusion, antiangiogenic therapy plus

chemotherapy achieved an ORR of 33.7%, a median PFS of 6.5 months

and a median OS of 20.3 months with tolerable toxicity in patients

with PRROC. Moreover, ascites and administering treatment as a

third-line or above therapy independently predicted an unfavourable

survival rate in these patients. Future studies should consider

increasing the sample size, including a control group and extending

the follow-up period to further investigate the long-term efficacy

and safety of antiangiogenic therapy plus chemotherapy in patients

with PRROC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HL contributed to the study conception and design.

JX performed data collection and analysis. MT was responsible for

the interpretation of data. All authors contributed to drafting the

article. HL and MT confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study obtained permission from the Ethics

Committee of People's Hospital of Zhongshan City (approval no.

2024-033; Zhongshan, China). The patients signed the informed

consent form, or if the patient were unable to sign, their family

members signed the informed consent form on their behalf.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Momenimovahed Z, Tiznobaik A, Taheri S and

Salehiniya H: Ovarian cancer in the world: Epidemiology and risk

factors. Int J Womens Health. 11:287–299. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mazidimoradi A, Momenimovahed Z, Allahqoli

L, Tiznobaik A, Hajinasab N, Salehiniya H and Alkatout I: The

global, regional and national epidemiology, incidence, mortality,

and burden of ovarian cancer. Health Sci Rep. 5:e9362022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ali AT, Al-Ani O and Al-Ani F:

Epidemiology and risk factors for ovarian cancer. Prz Menopauzalny.

22:93–104. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zamwar UM and Anjankar AP: Aetiology,

epidemiology, histopathology, classification, detailed evaluation,

and treatment of ovarian cancer. Cureus. 14:e305612022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chandra A, Pius C, Nabeel M, Vishwanatha

JK, Ahmad S and Basha R: Ovarian cancer: Current status and

strategies for improving therapeutic outcomes. Cancer Med.

8:7018–7031. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Luvero D, Milani A and Ledermann JA:

Treatment options in recurrent ovarian cancer: Latest evidence and

clinical potential. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 6:229–239. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Singh N, Jayraj AS, Sarkar A, Mohan T,

Shukla A and Ghatage P: Pharmacotherapeutic treatment options for

recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother.

24:49–64. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Havasi A, Cainap SS, Havasi AT and Cainap

C: Ovarian Cancer-Insights into platinum resistance and overcoming

it. Medicina (Kaunas). 59:5442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Richardson DL, Eskander RN and O'Malley

DM: Advances in ovarian cancer care and unmet treatment needs for

patients with platinum resistance: A narrative review. JAMA Oncol.

9:851–859. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Elyashiv O, Aleohin N, Migdan Z, Leytes S,

Peled O, Tal O and Levy T: The poor prognosis of acquired secondary

platinum resistance in ovarian cancer patients. Cancers (Basel).

16:6412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liu ZL, Chen HH, Zheng LL, Sun LP and Shi

L: Angiogenic signaling pathways and anti-angiogenic therapy for

cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:1982023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Mei C, Gong W, Wang X, Lv Y, Zhang Y, Wu S

and Zhu C: Anti-angiogenic therapy in ovarian cancer: Current

understandings and prospects of precision medicine. Front

Pharmacol. 14:11477172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang T, Tang J, Yang H, Yin R, Zhang J,

Zhou Q, Liu Z, Cao L, Li L, Huang Y, et al: Effect of apatinib plus

pegylated liposomal doxorubicin vs pegylated liposomal doxorubicin

alone on platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: The APPROVE

randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 8:1169–1176. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B,

Reuss A, Poveda A, Kristensen G, Sorio R, Vergote I, Witteveen P,

Bamias A, et al: Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for

platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: The AURELIA Open-label

randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 32:1302–1308. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Geng A, Yang H, Wang Z and Wu C: Apatinib

plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel monotherapy for

platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer treatment: A

retrospective cohort study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 47:2264–2273. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD, Bakkum-Gamez JN,

Barroilhet L, Behbakht K, Berchuck A, Berek JS, Chen LM, Cristea M,

DeRosa M, et al: NCCN guidelines insights: Ovarian cancer, version

1.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 17:896–909. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Schwartz LH, Litiere S, de Vries E, Ford

R, Gwyther S, Mandrekar S, Shankar L, Bogaerts J, Chen A, Dancey J,

et al: RECIST 1.1-Update and clarification: From the RECIST

committee. Eur J Cancer. 62:132–137. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD, Bakkum-Gamez JN,

Barroilhet L, Behbakht K, Berchuck A, Chen LM, Cristea M, DeRosa M,

Eisenhauer EL, et al: Ovarian cancer, version 2.2020, NCCN clinical

practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

19:191–226. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Berek JS, Renz M, Kehoe S, Kumar L and

Friedlander M: Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum:

2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 155 (Suppl 1):S61–S85. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Vergote I, Gonzalez-Martin A, Lorusso D,

Gourley C, Mirza MR, Kurtz JE, Okamoto A, Moore K, Kridelka F,

McNeish I, et al: Clinical research in ovarian cancer: Consensus

recommendations from the Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup. Lancet

Oncol. 23:e374–e384. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Le T, Hopkins L, Baines KA, Rambout L, Al

Hayki M and Kee Fung MF: Prospective evaluations of continuous

weekly paclitaxel regimen in recurrent platinum-resistant

epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 102:49–53. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda

DG and Jain RK: Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using

antiangiogenics: Opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

15:325–340. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Qiu H, Li J, Liu Q, Tang M and Wang Y:

Apatinib, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor, suppresses tumor

growth in cervical cancer and synergizes with Paclitaxel. Cell

Cycle. 17:1235–1244. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Volk LD, Flister MJ, Chihade D, Desai N,

Trieu V and Ran S: Synergy of nab-paclitaxel and bevacizumab in

eradicating large orthotopic breast tumors and preexisting

metastases. Neoplasia. 13:327–338. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Rapisarda A, Hollingshead M, Uranchimeg B,

Bonomi CA, Borgel SD, Carter JP, Gehrs B, Raffeld M, Kinders RJ,

Parchment R, et al: Increased antitumor activity of bevacizumab in

combination with hypoxia inducible factor-1 inhibition. Mol Cancer

Ther. 8:1867–1877. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Cesca M, Morosi L, Berndt A, Fuso Nerini

I, Frapolli R, Richter P, Decio A, Dirsch O, Micotti E, Giordano S,

et al: Bevacizumab-Induced inhibition of angiogenesis promotes a

more homogeneous intratumoral distribution of paclitaxel, improving

the antitumor response. Mol Cancer Ther. 15:125–135. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang H, Geng A, Wang Z and Wu C: Efficacy

and safety of apatinib combined with liposomal doxorubicin or

paclitaxel versus liposomal doxorubicin or paclitaxel monotherapy

in patients with recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J

Obstet Gynaecol Res. 49:1611–1619. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Fukuda T, Noda T, Uchikura E, Awazu Y,

Tasaka R, Imai K, Yamauchi M, Ichimura T, Yasui T and Sumi T:

Real-world efficacy and safety of bevacizumab for advanced or

recurrent mullerian cancer: A Single-institutional experience.

Anticancer Res. 43:3097–3105. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ford CE, Werner B, Hacker NF and Warton K:

The untapped potential of ascites in ovarian cancer research and

treatment. Br J Cancer. 123:9–16. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Simion L, Rotaru V, Cirimbei C, Stefan DC,

Gherghe M, Ionescu S, Tanase BC, Luca DC, Gales LN and Chitoran E:

Analysis of efficacy-to-safety ratio of angiogenesis-inhibitors

based therapies in ovarian cancer: A systematic review and

Meta-analysis. Diagnostics (Basel). 13:10402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang Y, Lin H, Ou Y, Fu H, Tsai C, Chien

CC and Wu C: Safety analysis of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer

patients. J Clin Med. 12:20652023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Verschraegen CF, Czok S, Muller CY, Boyd

L, Lee SJ, Rutledge T, Blank S, Pothuri B, Eberhardt S and Muggia

F: Phase II study of bevacizumab with liposomal doxorubicin for

patients with Platinum- and taxane-resistant ovarian cancer. Ann

Oncol. 23:3104–3110. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|