The Global Cancer Observatory reported that the top

seven types of cancer according to incidence rates in 2022 were

breast (23.8%), lung (9.4%), colorectal (8.9%) cervix uteri (6.9%),

thyroid (6.4%), corpus uteri (4.3%) and stomach (3.5%) cancer for

females. For males, the top seven by incidence were lung (15.2%),

prostate (14.2%), colorectal (10.4%), stomach (6.1%), liver (5.8%),

bladder (4.6%) and esophagus (3.5%) cancers. Similarly, the top

seven types of cancer according to mortality rates in 2022 were

breast (15.4%), lung (13.5%), colorectal (9.4%), cervix uteri

(8.1%), liver (5.5%), stomach (5.4%) and pancreas (5.1%) cancers

for females. For males the top seven by mortality rate were llung

(22.7%), liver (9.6%), colorectal (9.2%), stomach (7.9%), prostate

(7.3%), esophagus (5.9%) and pancreas (4.6%) cancer (1). These statistics demonstrate sex

differences in cancer incidence and mortality rates that can be

attributed to varying expression levels of hormone receptors and

associated genes involved in cancer occurrence and malignancy

mechanisms (2,3).

Estrogen, commonly recognized as a female hormone,

also significantly impacts males. Among the four types of estrogen,

estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), estriol and estetrol, E2 is the most

predominant in both males and premenopausal females. While E2

levels in males are lower compared with in premenopausal females,

they are comparable to or exceed those in postmenopausal females

(4,5). In males, E2 is primarily produced in

extragonadal tissues, particularly increasing in individuals with a

higher BMI (4–7). Estrogen inhibits bone resorption and

provides cardiovascular protection, essential for maintaining

health in premenopausal women. However, after menopause, ovarian

estrogen production ceases, diminishing these protective effects

and increasing the risk of developing diseases, such as

cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis (8–12).

Additionally, in postmenopausal women, estrogen is mainly produced

in peripheral tissues, heightening the risk of developing breast

cancer (13,14).

Androgens, commonly known as male hormones, notably

impact females as well. In males, androgens are secreted by the

testes and adrenal glands; whereas in females, androgens are

produced by the ovaries and adrenal glands (15). Androgens bind to androgen receptors

(AR) in various tissues, including the prostate, seminal vesicles

and skeletal muscle, to regulate physiological activities, sperm

production and cancer growth in males (16,17).

In females, precursor substances of androgen, such as

androstenedione, are more likely to convert to estrogen compared

with androgens and act on estrogen receptors (ER) (18). Excessive androgen secretion in

females can worsen endocrine disorders such as polycystic ovary

syndrome and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (19,20).

The expression and activation of sex hormone

receptors serve a significant role in the progression and

malignancy of breast and prostate cancer, influencing tumor growth,

metastasis and response to treatment (21). While a direct linear correlation

between cancer stage and hormone receptor expression is not

consistently observed (22,23), sex hormone receptor status serves a

key role in determining treatment options and prognosis at various

stages of cancer (24). In the

early stages of cancer (stage 1 or 2, according to the AJCC Cancer

Staging Manual), cancer cell growth is mainly promoted in a sex

hormone-dependent manner, so that it may be treated with hormone

therapy. However, in the advanced stages of cancer (stage 3 or 4),

hormone receptor expression levels often diminish or become less

predictive of treatment efficacy, requiring more aggressive

therapies, such as chemotherapy or targeted therapy (25,26).

ER-low or ER-negative (−) patients with breast cancer have a higher

recurrence rate and show distinct clinicopathological findings

compared with ER-high patients. The 5-year recurrence rates are

5.1% for ER-high, 7.4% for ER-low and 9.7% for ER-negative

patients, with ER-negative cases showing significantly worse

outcomes (P<0.001). ER-high patients typically have lower tumor

grades, lower Ki-67 proliferation indices, and are associated with

the luminal A subtype, which responds well to hormone therapy. By

contrast, ER-negative patients present with higher tumor grades,

significantly elevated Ki-67 indices, and a higher prevalence of

triple-negative breast cancer, often leading to a poorer prognosis

(24). Furthermore, hormone

receptor-positive types of cancer, such as luminal A and B, respond

well to hormone therapies, while HER2-positive and triple-negative

breast cancer (TNBC) subtypes often require more aggressive

treatments, such as targeted therapy or chemotherapy (27–29).

Among these subtypes, both luminal subtypes typically show positive

ER and progesterone receptor (PR) expression, while luminal B

breast cancer generally displays increased HER2 expression levels

compared with luminal A. Luminal B breast cancer is also associated

with higher proliferation rates (e.g., Ki-67 index), increased HER2

expression and a poor prognosis, indicating more aggressive

clinical characteristics (27–30).

Prostate cancer is similarly categorized by its

dependence on AR signaling, with advanced cases evolving into

castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), which requires more

intensive treatments. Hormone-sensitive prostate cancer, which

typically describes most early-stage cases, is commonly treated

with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) (31). However, CRPC requires more

aggressive treatments, such as second-line hormonal therapies, such

as enzalutamide or chemotherapy (32). Thus, the expression levels of

hormone receptors in the early stages of cancer are a major factor

in treatment decisions. However, in advanced stages, their

predictive value for treatment decreases due to reduced dependence

on hormones.

Recent studies have reported that AR and ER

signaling pathways are closely associated, particularly in breast

cancer, where AR can either suppress or enhance estrogen receptor α

(ERα) activity depending on the context (33,34).

In ER-positive (+) breast cancer, ARs often act as a tumor

suppressor by inhibiting ERα-driven tumorigenesis, with AR

activation showing significant anti-tumor effects, even in cases of

resistance to ER and CDK4/6 inhibitors (35). AR redistributes ER and its

co-activators on chromatin, suppressing ER-regulated genes and

upregulating AR target genes, which correlates with improved

survival in patients with ER(+) breast cancer (36). However, AR can also promote

oncogenic functions in the context of androgen excess, where

androgens act as precursors to estrogen (37). This leads to overstimulation of

estrogen-regulated gene expression, driving tumor proliferation and

progression in ER-positive breast cancer (34). In CRPC, estrogen receptor β (ERβ)

activation reduces AR expression, inducing apoptosis and acting as

a tumor suppressor. These findings highlight the key role of AR and

ER interactions in cancer progression and present opportunities for

targeted therapies (38).

While cancer research spans numerous fields of

research, studies focusing on sex-specific differences are

currently limited. Addressing these differences may lead to

significant breakthroughs in cancer prevention and treatment.

Specifically, hormones can act on their receptors to influence the

expression of hormone-related transcription factors, which in turn

can affect the expression of oncogenes or tumor suppressors

(39). Understanding how sex

hormone receptors interact with common transcription factors in

different types of cancer may serve to identify novel therapeutic

targets, which could aid in the development of personalized

treatment strategies and thereby maximize the efficacy of cancer

therapies.

ERα is a pivotal molecule in the development and

progression of various types of cancer. In breast cancer, ERα is

associated with tumor progression and is upregulated in ~75% of

breast cancer tissues, in contrast to ~10% in healthy tissues

(50). ERα is more prevalent in the

luminal A type, compared with the basal type of breast cancer. ERα

interacts with estrogen to promote tumor growth (51). Given these properties, anti-hormone

therapies that target ERα, such as aromatase inhibitors, tamoxifen

and fulvestrant, have proven to be effective in breast cancer

(52,53).

Aromatase inhibitors reduce estrogen levels by

inhibiting the enzyme aromatase, which is responsible for

converting the androgen hormone androstenedione and androstenediol

into E1 and E2, respectively. As a result, these inhibitors are

used in the treatment of ER(+) breast cancer to lower estrogen

levels, thus suppressing cell proliferation and invasion (54). By contrast, tamoxifen is an

anti-estrogen drug that blocks the activity of estrogen in breast

cancer. Tamoxifen directly binds to ERα, which prevents estrogen

from exerting its effects, thereby inhibiting cell proliferation

and tumor growth (55). The

clinical study by Arpino et al (56) on patients with breast cancer

demonstrated that the ER(+)/PR(−) breast cancer group is less

sensitive to tamoxifen, which targets ER, compared with the

ER(+)/PR(−) breast cancer group. This is because tamoxifen inhibits

the estrogen effect, which influences the expression of the PR gene

(57). As a result, PR(−) patients

experience reduced efficacy from tamoxifen treatment. Moreover,

these patients tend to exhibit increased expression levels of other

receptors, such as HER-1 and HER-2, which contributes to more

aggressive tumor characteristics, including therapy resistance,

faster proliferation and a higher probability of metastasis.

Specifically, HER-2 positive tumors are known to exhibit resistance

to tamoxifen therapy, while HER-1 expression is predominantly

observed in ER-negative tumors, which are associated with poor

prognosis (58). Therefore,

tamoxifen and fulvestrant are specifically used in ER(+) breast

cancer, regardless of PR status, but their efficacy may vary

depending on the presence or absence of PR. Additionally, ERα is

comprised of 595 amino acids with a molecular weight of 66 kDa, and

alternative splicing results in several isoforms such as ERα46 and

ERα36, with the ERα46 isoform acting as a competitive inhibitor

when co-expressed with ERα66 (59–61).

In prostate cancer, ERα promotes cell proliferation

and inhibits apoptosis, thereby facilitating tumor growth (62). Notably, ERα expressed in stromal

tissue has been shown to stimulate the growth of prostatic

epithelium through growth factors (63). An in vivo study has

demonstrated that knocking down ERα suppresses tumor growth

(64), and research indicates that

patients with high ERα expression levels have poor prognoses

(65). In the majority of prostate

cancer subtypes, ERα activation is associated with tumorigenesis

and cancer progression (66–68).

ERα typically promotes cancer cell proliferation by activating

pathways such as IL-6 signaling, which supports cell survival and

resistance to ADT. This is particularly relevant in CRPC, where

androgen-independent mechanisms serve a pivotal role in sustaining

tumor growth (66,67). In aggressive prostate cancer

subtypes, including neuroendocrine prostate cancer and CRPC,

elevated ERα levels contribute to increased malignancy and

facilitate cancer cell survival and invasiveness, often through

interactions with AR-mediated pathways (68).

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the most common

type of lung cancer, is characterized by ERα promoting tumor

progression by enhancing macrophage infiltration, which alters the

tumor microenvironment to favor cancer growth and increases cell

invasion (73). Clinical data also

demonstrates that within the same elderly cancer patient group,

women have a higher survival rate compared with men. Lung

adenocarcinoma, a common subtype of NSCLC, commonly occurs in

non-smokers, with a higher incidence rate in women (19.6%) compared

with men (11.8%) (74).

Premenopausal women with lung adenocarcinoma had a median survival

of 643 days compared with 735 days for postmenopausal women

(P=0.01). Additionally, premenopausal women presented with more

advanced stages of the disease, with 66% in stage IV compared with

53% in postmenopausal women. This highlights the significant impact

of menopausal status on disease progression and survival outcomes.

A study by Hsu et al (75)

indicated that E2 stimulates cancer cell migration, while ER

antagonists such as tamoxifen, targeting the estrogen signaling

pathway, inhibit lung cancer cell growth. Another study reported

that women >60 years have a survival advantage compared with

younger women, though this age effect is not observed in men

(76).

Meanwhile, research on gastric cancer suggests that

ERα may have a dual role. A study showed that transfection-induced

overexpression of ERα decreases β-catenin expression, thus

inhibiting cell proliferation and invasion (77). Additionally, ERα and ERβ mRNA levels

in tumors, compared with normal tissues, have been associated with

increased metastatic potential in gastric cancer (78). By contrast, it has also been

suggested that knockdown of ERα inhibits the proliferation,

migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells by regulating the

expression of factors such as p53 and CDK inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A),

associated with poor prognosis in patients (79).

Colon cancer is significantly influenced by estrogen

and exhibits varying effects depending on which estrogen receptor

it interacts with. ERα promotes the development and proliferation

of colon cancer cells (80,81). The type of ERs interacting with

estrogen varies with colon cancer stage, with ERα predominantly

driving tumor progression in late stages. Conversely, the isoform

ERα36 shows lower expression in tumor tissue compared with healthy

colorectal tissue and decreases with advancing Dukes' stage

(A+B>C+D, P=0.017) and lymph node metastasis stage (N0>N1/N2,

P=0.049), suggesting a function opposite to full-length ERα66

(82).

In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common

type of liver cancer, ERα is expressed at lower levels compared

with adjacent normal tissue, and its promoter is hypermethylated

(83). Hou et al (84) reported that ERα acts as a tumor

suppressor by upregulating the expression of tyrosine phosphatase

receptor type O, which promotes apoptosis and inhibits cell

proliferation. However, in HCV-related HCC, ERα mRNA and protein

expression levels are elevated, and increased ERα expression is

associated with increased levels of inflammatory and oncogenic

genes, such as NF-κB and cyclin D1, suggesting a role in promoting

liver cancer progression (85).

In breast cancer, ERβ generally exhibits lower

expression levels and has a weak negative correlation with ERα

(Spearman R=−0.18, P=2.2×10−16) (91). ERβ is more abundantly expressed in

basal-like or normal-like breast cancer subtypes (91). In ERα(+) breast cancer, ERβ

suppresses ERα and thus inhibits tumor growth. Conversely, ERβ can

act as a carcinogen in ERα(−) breast cancer (89). Moreover, ERβ interacts with various

signaling pathway molecules including AR, p53, E-cadherin, cell

cycle arrest molecules, phosphatase and PTEN, PI3K and AKT, all of

which contribute to either inhibiting or promoting cancer growth

(92). Notably, stable expression

of ERβ in the ERα(+) cell line MCF7 results in decreased cell

proliferation. Of the 921 differentially expressed genes after E2

treatment in ERβ(+) compared with ERβ(−) breast cancer cells, 424

had ERβ binding sites within 10 kb. These target genes are crucial

in regulating cell proliferation, death, differentiation, motility,

adhesion, signal transduction and transcription (93).

In the context of ovarian cancer, it has been

hypothesized that ERβ serves as a tumor suppressor. Indeed, studies

have demonstrated that in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC),

comprising 90% of ovarian cancer, the expression of ERβ is

diminished in tumor tissues compared with normal tissues (102). Overexpression of ERβ has been

observed to suppress the expression and activity of ERα, and to

decrease levels of pAKT, cyclin D1 and cyclin A2. An in vivo

study employing orthotopic xenograft mouse models showed that

overexpression of ERβ curbs tumor growth (103). In EOC, ERβ interacts with an

indole derivative

(3-{[2-chloro-1-(4-chlorobenzyl)-5-methoxy-6-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl]methylene}-5-hydroxy-6-methyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-indol-2-one)

to inhibit ovarian cancer cell proliferation (104).

Lung cancer studies, particularly in NSCLC, suggest

that ERβ facilitates tumor progression and adversely affects

patient prognosis (95,105). ERβ expression positively

correlates with tumor size, lymph node metastasis, clinical stage

and differentiation. Silencing ERβ in vitro reduces cell

invasion and colony formation (105). Overexpression of ERβ in in

vivo mouse models has been shown to accelerate tumor

progression via the ERβ/circ-TMX4/miR-622/CXCR4 signaling pathway

(106).

In gastric cancer, ERβ operates as a tumor

suppressor and manifests at reduced levels in gastric cancer

tissues compared with normal gastric mucosa (107,108). Knockdown of ERβ in gastric cancer

cell lines AGS and MKN45 activates growth arrest and DNA damage

inducible α, leading to increased apoptosis and autophagy through

inhibition of the MAPK pathway. Furthermore, ERβ knockdown results

in fewer colonies formed (109).

Clinical studies have reported a negative correlation between ERβ

expression levels, tumor grade and Lauren type in gastric cancer

(110).

In liver cancer, ERβ also acts as a tumor

suppressor, notably in HCC, where ERβ interacts with E2 to exert

anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory effects (116). It has been reported that ERβ

induces the expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 and

inhibits the JAK1-STAT6 pathway, preventing the polarization of

tumor-associated macrophages to the M2 phenotype, thereby

inhibiting HCC growth (117).

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma treatment with the ERβ antagonist

KB9520 has shown to increase apoptosis and reduce cell

proliferation in vitro using HuH-28 cells and in vivo

in a thioacetamide-induced experimental model of intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma (118). These

findings collectively affirm that ERβ functions as a tumor

suppressor in liver cancer.

AR was discovered in the 1960s, and since then, its

structural functions and mechanisms have been extensively studied

(119–122). AR consists of several domains:

NTD, DBD, hinge region, LBD and CTD. Similar to ERβ, AF-1 is

located in the NTD and AF-2 is in the LBD. The hinge region,

positioned between the DBD and LBD, contains the nuclear

localization signal, facilitating the translocation of AR from the

cytoplasm to the nucleus (120–122). Although the functions of AR are

well documented in prostate cancer, its roles in other cancer types

are less clearly understood.

In prostate cancer, AR promotes tumor progression. A

previous study reported that IL-6 activates the NTD of AR in LNCaP

cells, enhancing cell proliferation via MAPK and signal transducer

and activator of STAT3 signaling pathways (123). Consequently, primary cancer

therapy for prostate cancer frequently utilizes ADT, which aims to

inhibit androgens or block their binding to AR, thus suppressing

tumor growth (124). However, as

the cancer advances, it may evolve into CRPC, which resists both

ADT and drugs such as abiraterone and enzalutamide (125–127). Due to this resistance, extensive

research on ADT therapy continues to explore mechanisms of

resistance and develop novel therapeutic strategies (128,129). Shiota et al (130) investigated organelles generating

reactive oxygen species (ROS) following AR inhibition and reported

that ROS are primarily induced in peroxisomes through peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) activation. Additionally,

inhibiting PPARα reduced cell proliferation and restored

sensitivity to enzalutamide. Inhibition of enhancer of zeste

homolog 2 (EZH2) or achaete-scute homolog 1 (ASCL1) have been shown

to re-sensitize prostate cancer cells to enzalutamide. EZH2, a

component of the polycomb repressive complex 2, functions as a

histone methyltransferase. In CRPC, EZH2 can promote AR signaling

independent of its histone modification role, even in the absence

of androgens (100,131). ASCL1, a transcription factor

involved in neuroendocrine differentiation, is linked to resistance

against AR-targeted therapies, including enzalutamide, due to its

role in promoting neuroendocrine-like characteristics in prostate

cancer. Inhibiting either EZH2 or ASCL1 shifts the cancer cells

back to a phenotype more reliant on AR signaling, thereby restoring

sensitivity to enzalutamide (66).

In breast cancer, multiple studies have investigated

the antitumor activity of AR, highlighting its potential to

suppress estrogen-regulated tumorigenesis and improve clinical

outcomes, particularly in ER(+) breast cancer (36,132–135). AR activation displaces ER and key

co-activators such as p300 and SRC-3 from chromatin, leading to the

downregulation of ER-regulated genes and the upregulation of tumor

suppressor genes and AR target genes. This antitumor activity

remains effective even in ER(+) breast cancer resistant to CDK4/6

inhibitors (36,132). Conversely, in ER(−) breast cancer,

AR promotes tumor progression. Treatment with the AR agonist

dihydrotestosterone (DHT) has been shown to increase cell

proliferation, migration, invasion and metastasis, as confirmed

using in vivo mouse models (133). Additionally, AR is activated by

various signaling pathways, including the PI3K, MAPK and mTOR

pathways, further contributing to tumor progression (134,135).

Whether ARs act as a tumor suppressor or an oncogene

in lung cancer remains unresolved. Liu et al (142) reported that ARs impede cell

invasion in NSCLC and diminishes the expression of the oncogene

tumor protein D52 via the circular-SLCO1B7/microRNA (miR)-139-5p

axis, thereby impeding tumor progression. Additionally, miR-224-5p,

which hampers apoptosis and accelerates tumor growth, directly

targets ARs and patients with NSCLC with high AR expression levels

have a significantly longer overall survival rate [hazard ratio

(HR)=0.5, log rank P=8.9×10−16] (143). By contrast, Li et al

(144) demonstrated that treating

the NSCLC cell line A549 with luteolin suppressed AR expression and

subsequently reduced cell proliferation. Additionally, Recchia

et al (145) reported that

the interaction between AR and the EGFR-enhanced A549 cell

proliferation via the mTOR/CD1 pathway. Thus, further research into

the detailed mechanism of AR is essential.

In regards to gastric cancer, similar to lung

cancer, the precise role of AR is not well defined, but the

majority of studies suggest that AR promotes tumor progression. Liu

et al (146) reported that

AR upregulates the oncogenic miR-125b in gastric cancer, which

inhibits apoptosis and promotes proliferation. Conversely,

treatment with the AR antagonist bicalutamide induces apoptosis and

inhibits proliferation. Furthermore, Xia et al (147) found that the AR splice variant

AR-v12 is more highly expressed in tumor tissues compared with

normal tissues and upregulates myosin light chain kinase, enhancing

cell migration and invasion. Soleymani Fard et al (148) reported that >50% of the 60

patients with gastric cancer exhibited upregulated ARs, which were

significantly associated with the upregulation of EMT-related

genes, including Snail, β-catenin, Twist1 and STAT3. AR

upregulation is associated with poor survival outcomes (HR=3.478,

P=0.001), and treatment with enzalutamide has been found to inhibit

tumor progression.

The role of AR in colon cancer remains unclear.

Studies suggest that the activation of membrane-associated AR

inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway, induces apoptosis and subsequently

suppresses tumor growth in colorectal cancer (149,150). Conversely, Rodríguez-Santiago

et al (151) reported that

ARs promote tumor progression, noting that their upregulation in

tumor tissues is associated with increased tumor size,

differentiation and metastasis. AR activation not only diminishes

antitumor immune activity but also increases the secretion of

tumor-promoting factors from the nervous system, thereby

facilitating tumor growth.

In liver cancer, similarly to colon cancer, the role

of AR is not well-defined. Acosta-Lopez et al (152) observed increased expression levels

of AR in tumor tissues compared with normal tissues in HCC,

associating increased AR activity with poorer prognosis in advanced

HCC. Furthermore, Ren et al (153) suggested that mTORC1 phosphorylates

AR at serine residue 96, which promotes tumor progression.

Meanwhile, Ren et al (154)

reported that treatment with DHT escalates cell proliferation,

invasion and migration in the HepG2 cell line, while Ouyang et

al (155) determined that AR

inhibits cell migration and invasion in HCC cell lines HA22T and

SK-HEP-1 via the miR-325/ACP5 signaling pathway.

The present review investigated the effects of three

hormone receptors across seven major types of cancer. The impact of

sex hormone receptors on each type of cancer is summarized in

Table I. Studies on the influence

of these receptors on tumor progression have advanced considerably

in hormone-responsive organs, although their effects in

non-responsive organs remain less understood.

The sex hormones examined in the present study

activate mechanisms of cancer malignancy or suppression through

their respective receptors. In this process, various transcription

factors are known to regulate the expression of key molecules

involved in these mechanisms via sex hormone signaling. Prominent

transcription factors include specificity protein 1 (SP1),

ETS-related gene (ERG), β-catenin, activator protein 1 (AP-1),

c-Myc, NF-κB and STAT3. Table II

provides a summary of how these key transcription factors influence

cancer progression through their interactions with sex hormone

receptors.

SP1 is a transcription factor that binds to specific

promoter regions containing GC-rich sequences and serves a key role

in activating the expression of various genes. SP1 is known to

function as an oncogene through the three sex hormone receptors

examined in this study. In breast cancer, the ER/SP1 complex binds

to DNA, promoting the expression of estrogen-induced genes such as

c-Myc, creatine kinase B-type (CKB), cathepsin D, retinoic acid

receptor α (RARα) and heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27), thereby

facilitating tumor progression (156). In ovarian cancer, estrogen

stimulates the expression of genes related to angiogenesis in the

endometrium and endothelial cells through the SP1/ERβ complex, with

this abnormal angiogenesis promoting tumor growth and invasion

(157). Furthermore, in prostate

cancer, the AR/SP1 complex binds to the VEGF core promoter in

chromatin, and androgen increases VEGF expression via the SP1

binding site, driving angiogenesis and tumor progression (158).

ERG is a key transcription factor belonging to the

ETS family that serves a key role in various biological processes

such as angiogenesis, cell differentiation, migration and

metastasis (159,160). In prostate cancer, ERG is notably

upregulated due to gene fusion with transmembrane serine protease 2

(TMPRSS2), and this upregulation has been associated with

aggressive prostate cancer (159).

Setlur et al (159)

demonstrated that TMPRSS2-ERG expression increased following ERα

agonist treatment, which also led to increased prostate cancer cell

viability. Conversely, ERβ agonist treatment resulted in a decrease

in both TMPRSS2-ERG expression and cancer cell viability,

indicating that the impact on cancer progression varies depending

on whether ERα or ERβ is activated by estrogen stimulation.

Moreover, an in vitro study by Kohvakka et al

(160) demonstrated that the

abnormal expression of prostate cancer-specific long non-coding

RNAs (lncRNAs) further promotes tumor development and

progression.

β-catenin, a key molecule in the Wnt signaling

pathway, exerts varying effects on cancer malignancy depending on

the type of sex hormone receptor involved. Experimental

overexpression of ERα via vector-based transfection inhibits

β-catenin, thereby suppressing the growth, proliferation and

invasion of gastric cancer cells, halting their entry into the

G1/G0 phase and promoting apoptosis (77). Meanwhile, in prostate cancer,

androgen interacts with AR to promote tumor progression, whereas

estrogen stimulates cell proliferation specifically in

androgen-responsive prostate cancer (63,126).

Increased expression levels of β-catenin via ERβ increases the

incorporation of [methyl-3H]thymidine and upregulates cyclin D2

expression, promoting cell cycle progression (161). Furthermore, β-catenin stimulates

AR transcriptional activity through transcriptional intermediary

factor 2 and glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein 1, thereby

activating AR signaling. This activation increases androgen

affinity, reduces the efficacy of anti-androgen therapies and

accelerates tumor progression in prostate cancer (162).

The AP-1 family of transcription factors, including

c-Fos and c-Jun, increases cell proliferation in breast cancer via

E2-ERα signaling. However, through ERβ signaling, AP-1-mediated

transcription is suppressed by the recruitment of the

transcriptional repressor C-terminal binding protein, which

counteracts the proliferation driven by ERα (87,163).

In prostate cancer, AR not only mediates androgen-induced cancer

progression but also interacts with AP-1 to form a complex, wherein

they mutually inhibit each other's binding affinity to DNA-binding

sites (164,165).

Estrogen stimulation enhances the interaction

between c-Myc and ERα, with both binding closely to the VEGF

promoter. A study by Dadiani et al (166) demonstrated that estrogen activates

c-Myc expression via ERα in ERα(+) breast cancer cells, promoting

cell growth and proliferation while inhibiting differentiation.

Additionally, estrogen transiently induces the transcription of

VEGF, a key factor in angiogenesis, thereby facilitating cell

migration (166). By contrast, ERβ

signaling suppresses c-Myc transcription, modulating the expression

levels of proliferation-related genes. For instance, ERβ increases

the production of antiproliferative genes such as p21 and p27,

leading to G1 or G2 cell cycle arrest and

inhibiting the proliferation of breast and colorectal cancer cells

(112,167). Moreover, c-Myc is a major target

gene of AR signaling, with AR enhancing the transcription and

expression levels of c-Myc, thereby promoting prostate cancer cell

growth and progression. Consequently, c-Myc upregulation is

associated with the development and progression of prostate cancer

(168).

NF-κB is known to mutually inhibit ERα, yet when

co-activated, NF-κB modifies ERα function, leading to endocrine

resistance and promoting breast cancer metastasis and recurrence,

making ER(+) tumors more aggressive (169). In prostate cancer, the effects of

NF-κB vary depending on the receptor involved. Estrogen-activated

ERβ mediates the proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α, which

suppresses NF-κB activation, thereby reducing inflammation and

potentially inhibiting the development of malignant tumors

(170). Conversely, Zhang et

al (171) reported that NF-κB

expression activates AR promoter transcription, increasing AR

expression levels and cell proliferation while inhibiting

apoptosis. This ultimately promotes metastasis and angiogenesis,

thereby accelerating tumor progression.

STAT3 functions as a key transcription factor

involved in various cancer progression pathways, including cellular

transformation, proliferation, survival and angiogenesis, often

through its interaction with sex hormone receptors (172–174). In breast cancer cells, leptin

signaling increases ERα expression, which in turn enhances STAT3

activity, improving ERα-dependent cell viability and promoting

tumor progression (172–174). In lung cancer cells, STAT3

activation upregulates ERβ signaling, leading to increased cell

proliferation (173). In prostate

cancer, AR directly interacts with STAT3, enhancing its activity.

Yamamoto et al (174),

reported that AR activation neutralizes the inhibitory effects of

the STAT3 protein inhibitor PIAS3, thus protecting STAT3 from

inhibition. Since STAT3 is an oncogene that mediates cellular

transformation and promotes prostate cancer, its interaction with

AR further accelerates tumor progression.

To identify sex-specific key transcription factors

involved in hormone receptor-driven cancer progression across seven

major types of cancer (breast, prostate, ovarian, colon, lung,

liver and gastric cancer), a comprehensive data analysis approach

using the SignaLink 3.0 database (http://signalink.org) was employed. The SignaLink

database integrates experimentally validated and curator-inferred

protein-protein interactions (PPIs) and regulatory mechanisms from

multiple sources, focusing on homo sapiens to ensure

human-specific relevance. The dataset includes curated data from

OmniPath (https://www.omnipathdb.org),

BioGRID (https://thebiogrid.org), Reactome

(https://reactome.org) and ComPPI (https://comppi.linkgroup.hu/) (175).

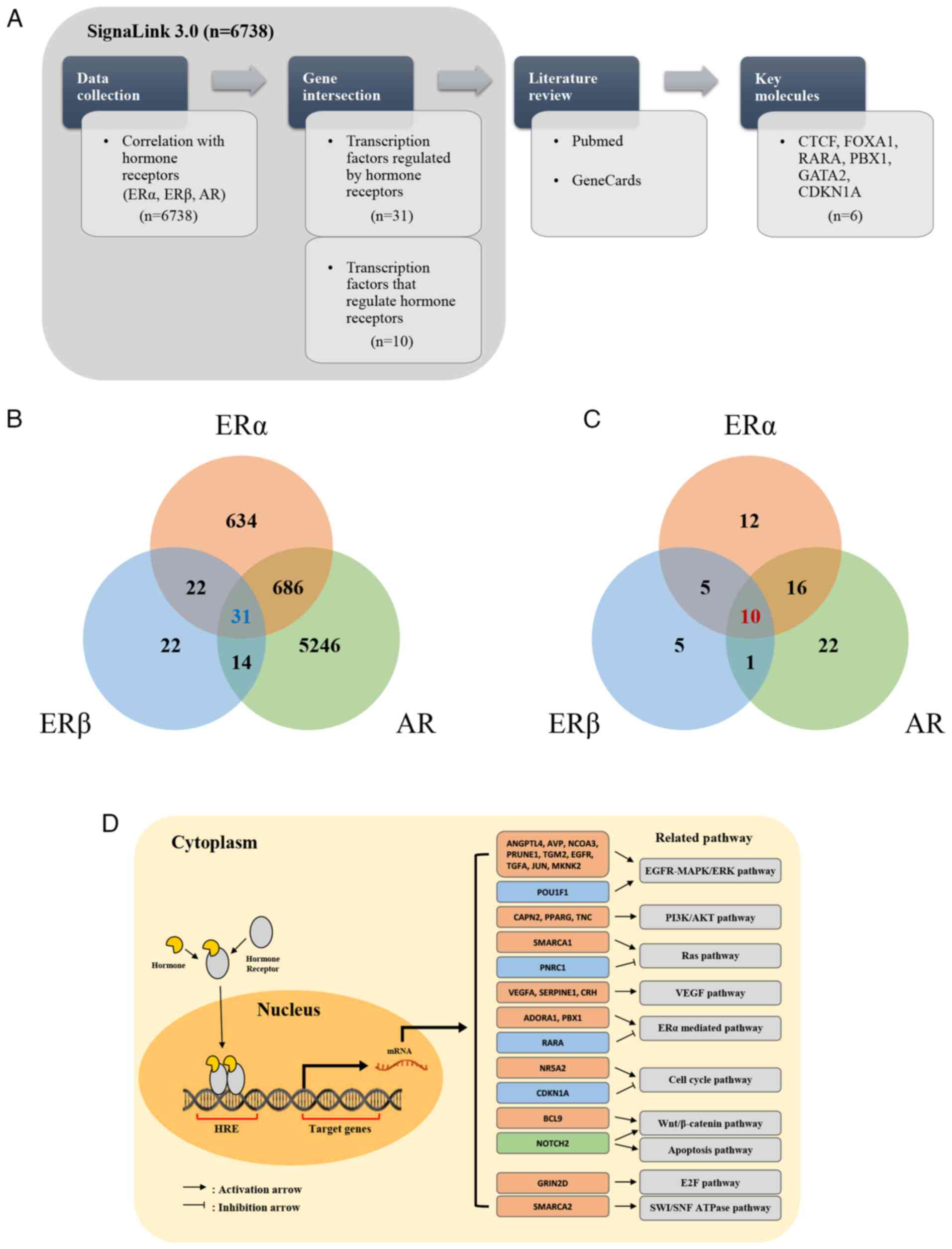

The initial analysis of SignaLink 3.0 identified

6,738 transcription factors associated with ERα, ERβ and AR. This

set was filtered to focus on transcription factors that either

regulate or are regulated by all three hormone receptors (ERα, ERβ

and AR). Through this process, 31 transcription factors were

identified that are regulated by all three hormone receptors and 10

transcription factors that regulate these receptors (Fig. 1; Table

III) (176–219). Notably, there was no overlap

between the two groups.

To further refine the selection, a text mining

approach was conducted by combining data from GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). GeneCards is

a comprehensive database that provides detailed information on

human genes, including their functions, interactions and

involvement in diseases (220).

GeneCards was used to explore the biological roles of each

transcription factor and utilized PubMed to analyze how they

interact with hormone receptors. The selection criteria focused on

transcription factors that, as evidenced in the literature, both

regulate and are regulated by at least two of the three hormone

receptors and have demonstrated significant roles in cancer

progression. Through this process, studies were identified that

demonstrated the critical roles of these transcription factors in

modulating hormonal signaling pathways, which are implicated in

sex-specific tumor biology. These interactions were further

analyzed to assess their impact on tumor progression, with a focus

on understanding the mechanisms by which these transcription

factors regulate hormone receptor activity across various types of

cancer.

These transcription factors are primarily known to

influence hormone-related cancer progression through various

pathways, including the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and the

Hippo-YAP/TAZ pathway. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling is a common pathway

modulated by multiple transcription factors such as PPARG and AR,

leading to enhanced tumor growth and survival, especially in

prostate cancer (191,207,208). SMARCA4 and the Hippo-YAP/TAZ

signaling pathway are implicated in lung cancer, where they promote

tumorigenicity by regulating gene transcription involved in cell

proliferation and metastasis (213). Consequently, six key transcription

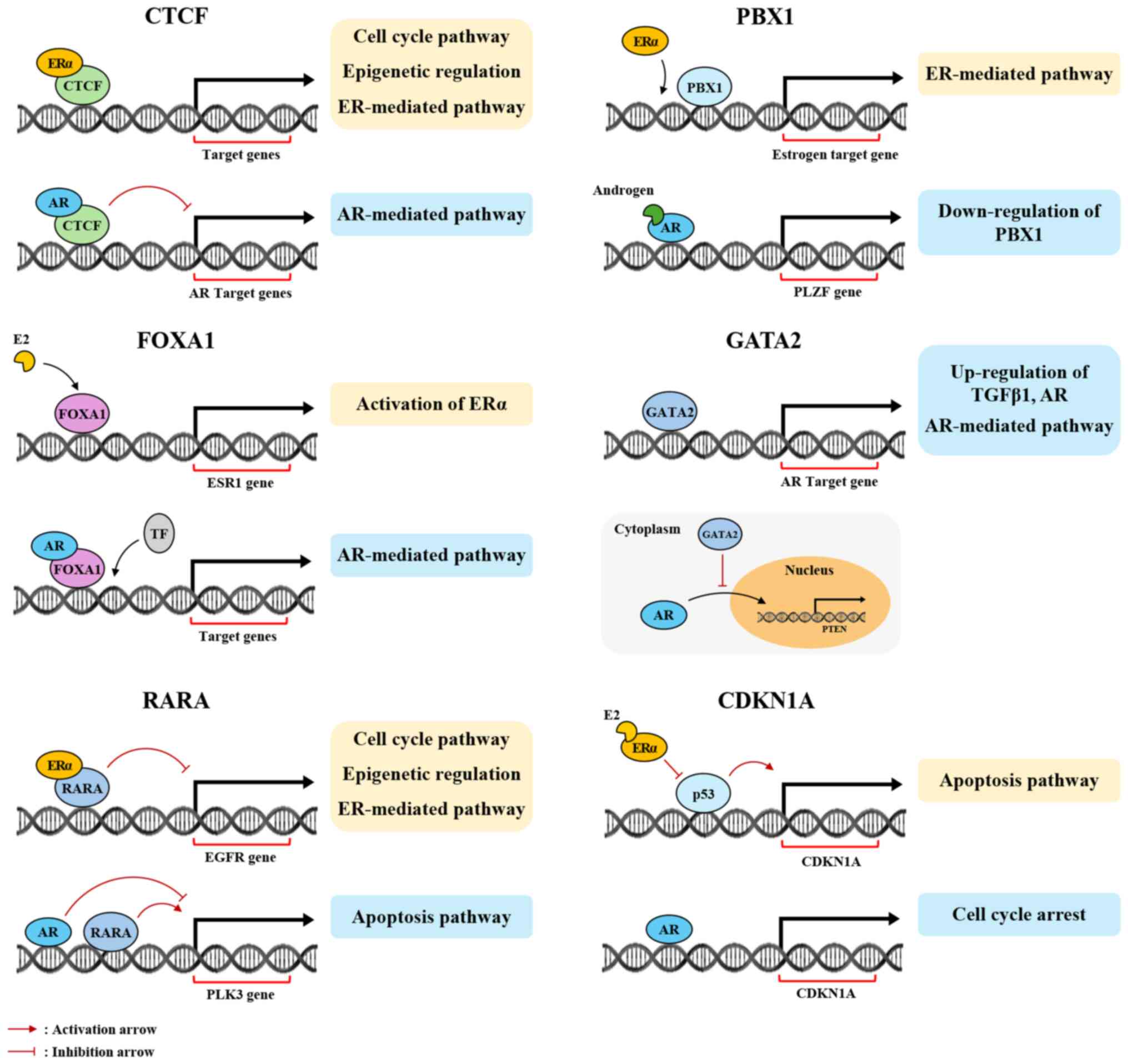

factors were identified: CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF), forkhead box

A1 (FOXA1), retinoic acid receptor α (RARA), PBX homeobox 1 (PBX1),

GATA binding protein 2 (GATA2) and CDKN1A, as candidate

hormone-related transcription factors. It was then investigated how

interactions between these transcription factors and hormone

receptors affect tumor progression, summarizing the pathways

influenced by these interactions (Fig.

2).

FOXA1 has been extensively researched in breast

cancer and is known to interact with ERα, regulating estrogen

responses and transcription activity and activating oncogene

expression (223–226). Additionally, FOXA1 has a positive

correlation with AR (r=0.8975, P<0.001) (227,228). Tsirigoti et al (229) reported that FOXA1 regulates AR

expression levels in TNBC and is inversely correlated with Snail

Family Transcriptional Repressor 1 (SNAI1) (Spearman's R=−0.377,

P<2.2×10−16), and suggested that in SNAI1-knockout

TNBC, FOXA1 induces AR expression, fostering basal-luminal

plasticity. In prostate cancer, FOXA1 is positively correlated with

ERβ (epithelial, ρ=0.41, P<0.001; stromal, ρ=0.354, P<0.001),

and FOXA1 knockdown via siRNA inhibits cell proliferation and

migration in LNCaP and PC-3 cell lines (230). FOXA1 is also implicated in

promoting tumor progression in prostate cancer and HCC through

AR-mediated signaling (231,232).

RARA has gained substantial attention in breast

cancer. It binds ERα to mediate transcription of ERα target genes

(233). Salvatori et al

(234) reported that, once

activated by retinoic acid, RARA suppresses EGFR expression, while

ERα, activated by E2, enhances EGFR expression. Nevertheless, in

the absence of ligands, ERα interacts with RARA to augment its

ability to suppress EGFR expression, functioning as a tumor

suppressor. RARA also participates in the AR-related transcription

network in prostate cancer, inversely regulating the expression of

target genes such as polo-like kinase 3 (PLK3). Specifically, RARA

increases PLK3 expression, while AR reduces it, contributing to

tumor progression (235). Notably,

in the HepG2 HCC cell line, ERβ does not interact with the RARA

promoter in the presence of estrogen, but upon 4-hydroxytamoxifen

(4-OHT) treatment, ERβ activates transcription of RARA (236).

PBX1 is predominantly studied in breast cancer,

specifically for its interaction with ERα compared with other

hormone receptors. PBX1 serves as both a transcription and pioneer

factor in the estrogen signaling pathway, binding to chromatin

before ERα to enhance its accessibility and elevate the expression

of estrogen-responsive genes linked to aggressive tumor behavior.

This mechanism supports PBX1 as a poor prognostic biomarker for

breast cancer (237,238). Although direct interactions

between PBX1 and AR are not documented, evidence suggests an

indirect regulatory pathway. Kikugawa et al (239) demonstrated that promyelocytic

leukemia zinc finger (PLZF), an AR-regulated tumor suppressor gene,

inhibits PBX1 expression. Thus, when androgen interacts with AR,

PLZF expression increases, which subsequently suppresses PBX1

expression and inhibits tumor progression.

GATA2 has been extensively studied in relation to

AR, particularly in prostate cancer, where it significantly affects

AR. GATA2 activates AR and the AR signaling pathway, which promotes

tumor progression. GATA2 also enhances the expression of TGFβ1,

further driving tumor progression through interaction with the AR

signaling pathway (240–242). In breast cancer, GATA2 inhibits AR

translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, thereby

suppressing the expression of the tumor suppressor PTEN (243). Treeck et al (244) showed that in the ovarian cancer

cell line HEC-1A, a threefold increase in GATA2 expression occurred

following ERβ knockdown. Additionally, GATA2 closely interacts with

TP53.

CDKN1A, also known as p21, is a key transcription

factor in various types of cancer. CDKN1A acts as a tumor

suppressor in breast cancer. The presence of estrogen leads to ERα

inhibiting p53 transcriptional activity, which reduces CDKN1A

expression and promotes tumor progression (245,246). Conversely, treatment with

tamoxifen or ERα inhibitors elevates CDKN1A expression and

decreases cell proliferation (245–247). ERβ also regulates CDKN1A

indirectly; in breast cancer, ERβ suppresses CDKN1A expression in

the presence of wild-type p53, but increases CDKN1A expression

levels in cases with mutant p53, as demonstrated in vitro

(248). The effects of ERβ have

been explored in ovarian cancer; He et al (249) concluded that LY500307, an ERβ

agonist, increases CDKN1A levels and apoptosis in ovarian cancer

stem cells. Kim et al (201) showed that the interplay between AR

and CDKN1A in prostate cancer demonstrates AR inhibiting cyclin

D1/2 and CDK4/6 transcription while increasing CDKN1A

transcription, leading to cell cycle arrest and reduced cell

proliferation.

Studies on the interaction between hormone

receptors and their transcription factors in cancer are limited and

mainly focused on breast cancer. This focus is due to the high

hormone dependency of breast cancer, with the majority of cases

expressing hormone receptors, especially estrogen receptors,

crucial for cancer cell growth and progression (250). Prostate cancer, also sensitive to

hormones, shows significant influence from androgen receptors in

its development and progression (251,252). By contrast, cancers such as

gastric and lung cancer are less dependent on hormone signaling,

resulting in fewer studies and less evidence on the impact of

hormone receptor interactions. The established role of hormone

therapy in treating breast and prostate cancer further stimulates

research in these areas, while the absence of similar therapeutic

approaches in other types of cancer restricts research on hormone

receptor interactions.

In hormone-dependent types of cancer such as breast

and prostate cancer, the interplay between AR, ER and other hormone

receptors serves a key role in tumor progression and therapy

resistance. In ER(+) breast cancer, when ER signaling is inhibited,

AR can compensate by becoming more active, potentially driving

tumor progression or resistance to treatment (253). Similarly, ER may assume a more

prominent role when AR activity is diminished. This compensatory

relationship also extends to other types of cancer such as prostate

cancer, where AR is the main driver of tumor growth, but ER can

contribute to cancer progression under certain conditions (254). The compensatory dynamics between

AR and ER underscore the need for therapies that target both

receptors simultaneously to prevent one from compensating for the

inhibition of the other (255).

The interactions between these hormone receptors are important in

understanding cancer malignancy and developing more effective,

comprehensive therapeutic strategies.

The present study underscores the roles of

sex-specific hormone receptors ERα, ERβ and AR across seven types

of pan-cancer, highlighting their interactions with key

transcription factors such as CTCF, FOXA1, RARA, PBX1, GATA2 and

CDKN1A, and their impact on tumor progression. In conclusion, sex

hormone receptors can either function as oncogenes or tumor

suppressors depending on the type of cancer, and may exhibit both

roles within a single tumor. Moreover, key transcription factors

that interact with these hormone receptors serve crucial roles in

regulating cancer prognosis and tumor progression. In certain types

of cancer closely associated with sex hormones, such as breast and

prostate cancer, hormone receptors significantly influence cancer

prognosis and progression. Utilizing these sex-specific

characteristics in cancer treatments enables precision medicine

tailored to the unique characteristics of each patient, and

transcription factors that interact with sex hormone receptors in

pan-cancer may serve as novel anticancer therapeutic targets. To

advance therapeutic strategies, further in-depth studies are

essential in several areas: The molecular mechanisms that underlie

the dual roles of sex hormone receptors as oncogenes and tumor

suppressors, the specific interactions between hormone receptors

and transcription factors in various types of cancer, and the

development of targeted therapies that exploit these interactions.

Additionally, further research is required to explore the

sex-specific differences in cancer biology and their implications

for treatment, as well as the potential for personalized medicine

approaches based on hormone receptor status and transcription

factor profiles.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Research

Foundation of Korea (grant nos. 2022R1F1A1076029 and

2022R1A2C1093335).

Not applicable.

Conceptualization was conducted by JK and SYK.

Formal analysis and data interpretation were conducted by JK, HB,

CS, EK and SYK. Literature analysis was conducted by JK, HB and CS.

Writing of the original draft was conducted by JK, HB, CS and SYK.

Reviewing and editing of the manuscript was conducted by JK, HB,

CS, EK and SYK. Visualization was conducted by JK and SYK.

Supervision was conducted by JK, EK and SYK. Project administration

was conducted by EK and SYK. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shen X, Jain A, Aladelokun O, Yan H,

Gilbride A, Ferrucci LM, Lu L, Khan SA and Johnson CH: Asparagine,

colorectal cancer, and the role of sex, genes, microbes, and diet:

A narrative review. Front Mol Biosci. 9:9586662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fuentes N, Silva Rodriguez M and Silveyra

P: Role of sex hormones in lung cancer. Exp Biol Med (Maywood).

246:2098–2110. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Coelingh Bennink HJT, Prowse A, Egberts

JFM, Debruyne FMJ, Huhtaniemi IT and Tombal B: The loss of

estradiol by androgen deprivation in prostate cancer patients shows

the importance of estrogens in males. J Endocr Soc. 8:bvae1072024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Frederiksen H, Johannsen TH, Andersen SE,

Albrethsen J, Landersoe SK, Petersen JH, Andersen AN, Vestergaard

ET, Schorring ME, Linneberg A, et al: Sex-specific estrogen levels

and reference intervals from infancy to late adulthood determined

by LC-MS/MS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 105:754–768. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gates MA, Mekary RA, Chiu GR, Ding EL,

Wittert GA and Araujo AB: Sex steroid hormone levels and body

composition in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 98:2442–2450. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Marriott RJ, Murray K, Adams RJ, Antonio

L, Ballantyne CM, Bauer DC, Bhasin S, Biggs ML, Cawthon PM, Couper

DJ, et al: Factors associated with circulating sex hormones in men:

Individual participant data meta-analyses. Ann Intern Med.

176:1221–1234. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Simpson ER, Misso M, Hewitt KN, Hill RA,

Boon WC, Jones ME, Kovacic A, Zhou J and Clyne CD: Estrogen-the

good, the bad, and the unexpected. Endocr Rev. 26:322–330. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gandhi N, Omer S and Harrison RE: In vitro

cell culture model for osteoclast activation during estrogen

withdrawal. Int J Mol Sci. 25:61342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hughes DE, Dai A, Tiffee JC, Li HH, Mundy

GR and Boyce BF: Estrogen promotes apoptosis of murine osteoclasts

mediated by TGF-beta. Nat Med. 2:1132–1136. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Srivastava S, Toraldo G, Weitzmann MN,

Cenci S, Ross FP and Pacifici R: Estrogen decreases osteoclast

formation by down-regulating receptor activator of NF-kappa B

ligand (RANKL)-induced JNK activation. J Biol Chem. 276:8836–8840.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gavali S, Gupta MK, Daswani B, Wani MR,

Sirdeshmukh R and Khatkhatay MI: LYN, a key mediator in

estrogen-dependent suppression of osteoclast differentiation,

survival, and function. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1865:547–557. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kharb R, Haider K, Neha K and Yar MS:

Aromatase inhibitors: Role in postmenopausal breast cancer. Arch

Pharm (Weinheim). 353:e20000812020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Arumugam A, Lissner EA and Lakshmanaswamy

R: The role of hormones and aromatase inhibitors on breast tumor

growth and general health in a postmenopausal mouse model. Reprod

Biol Endocrinol. 12:662014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Parish SJ, Simon JA, Davis SR, Giraldi A,

Goldstein I, Goldstein SW, Kim NN, Kingsberg SA, Morgentaler A,

Nappi RE, et al: International society for the study of women's

sexual health clinical practice guideline for the use of systemic

testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. J Sex

Med. 18:849–867. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Van-Duyne G, Blair IA, Sprenger C,

Moiseenkova-Bell V, Plymate S and Penning TM: The androgen

receptor. Vitam Horm. 123:439–481. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tsai CC, Yang YSH, Chen YF, Huang LY, Yang

YN, Lee SY, Wang WL, Lee HL, Whang-Peng J, Lin HY, et al: Integrins

and actions of androgen in breast cancer. Cells. 12:21262023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Naamneh Elzenaty R, du Toit T and Flück

CE: Basics of androgen synthesis and action. Best Pract Res Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 36:1016652022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bienenfeld A, Azarchi S, Lo Sicco K,

Marchbein S, Shapiro J and Nagler AR: Androgens in women:

Androgen-mediated skin disease and patient evaluation. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 80:1497–1506. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang R, Hu K, Bai H, Liu H, Pu Y, Yang C,

Liu Q and Fan P: Increased oxidative stress is associated with

hyperandrogenemia in polycystic ovary syndrome evidenced by

oxidized lipoproteins stimulating rat ovarian androgen synthesis in

vitro. Endocrine. 84:1238–1249. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Paakinaho V and Palvimo JJ: Genome-wide

crosstalk between steroid receptors in breast and prostate cancers.

Endocr Relat Cancer. 28:R231–R250. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Amirghofran Z, Monabati A and Gholijani N:

Androgen receptor expression in relation to apoptosis and the

expression of cell cycle related proteins in prostate cancer.

Pathol Oncol Res. 10:37–41. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Bodner K, Laubichler P, Kimberger O,

Czerwenka K, Zeillinger R and Bodner-Adler B: Oestrogen and

progesterone receptor expression in patients with adenocarcinoma of

the uterine cervix and correlation with various clinicopathological

parameters. Anticancer Res. 30:1341–1345. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yoon K, Park Y, Kang E, Kim E, Kim JH, Kim

SH, Suh KJ, Kim SM, Jang M, Yun BR, et al: Effect of estrogen

receptor expression level and hormonal therapy on prognosis of

early breast cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 54:1081–1090. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC,

Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR and

Winchester DP: The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual:

Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more

‘personalized’ approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin.

67:93–99. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Giuliano AE, Edge SB and Hortobagyi GN:

Eighth edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: Breast cancer.

Ann Surg Oncol. 25:1783–1785. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sørlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T,

Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey

SS, et al: Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas

distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 98:10869–10874. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cheang MCU, Chia SK, Voduc D, Gao D, Leung

S, Snider J, Watson M, Davies S, Bernard PS, Parker JS, et al: Ki67

index, HER2 status, and prognosis of patients with luminal B breast

cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 101:736–750. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs

H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M,

et al: Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2

for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med.

344:783–792. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Chen X, Sanders ME,

Chakravarthy AB, Shyr Y and Pietenpol JA: Identification of human

triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for

selection of targeted therapies. J Clin Invest. 121:2750–2767.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Huggins C and Hodges CV: Studies on

prostatic cancer. I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and of

androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of

the prostate. 1941. J Urol. 167:948–952. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Scher HI and Sawyers CL: Biology of

progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: Directed

therapies targeting the androgen-receptor signaling axis. J Clin

Oncol. 23:8253–8261. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gu G, Tian L, Herzog SK, Rechoum Y,

Gelsomino L, Gao M, Du L, Kim JA, Dustin D, Lo HC, et al: Hormonal

modulation of ESR1 mutant metastasis. Oncogene. 40:997–1011. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kolyvas EA, Caldas C, Kelly K and Ahmad

SS: Androgen receptor function and targeted therapeutics across

breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res. 24:792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Peters AA, Buchanan G, Ricciardelli C,

Bianco-Miotto T, Centenera MM, Harris JM, Jindal S, Segara D, Jia

L, Moore NL, et al: Androgen receptor inhibits estrogen

receptor-alpha activity and is prognostic in breast cancer. Cancer

Res. 69:6131–6140. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hickey TE, Selth LA, Chia KM, Laven-Law G,

Milioli HH, Roden D, Jindal S, Hui M, Finlay-Schultz J, Ebrahimie

E, et al: The androgen receptor is a tumor suppressor in estrogen

receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Med. 27:310–320. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Secreto G, Girombelli A and Krogh V:

Androgen excess in breast cancer development: Implications for

prevention and treatment. Endocr Relat Cancer. 26:R81–R94. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Gehrig J, Kaulfuß S, Jarry H, Bremmer F,

Stettner M, Burfeind P and Thelen P: Prospects of estrogen receptor

β activation in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate

cancer. Oncotarget. 8:34971–34979. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lung DK, Reese RM and Alarid ET: Intrinsic

and extrinsic factors governing the transcriptional regulation of

ESR1. Horm Cancer. 11:129–147. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Jensen EV, Desombre ER, Kawashima T,

Suzuki T, Kyser K and Jungblut PW: Estrogen-binding substances of

target tissues. Science. 158:529–530. 1967. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kato S, Endoh H, Masuhiro Y, Kitamoto T,

Uchiyama S, Sasaki H, Masushige S, Gotoh Y, Nishida E, Kawashima H,

et al: Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation

by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science. 270:1491–1494. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Bunone G, Briand PA, Miksicek RJ and

Picard D: Activation of the unliganded estrogen receptor by EGF

involves the MAP kinase pathway and direct phosphorylation. EMBO J.

15:2174–2183. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Tremblay A, Tremblay GB, Labrie F and

Giguère V: Ligand-independent recruitment of SRC-1 to estrogen

receptor beta through phosphorylation of activation function AF-1.

Mol Cell. 3:513–519. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Yi P, Wang Z, Feng Q, Pintilie GD, Foulds

CE, Lanz RB, Ludtke SJ, Schmid MF, Chiu W and O'Malley BW:

Structure of a biologically active estrogen receptor-coactivator

complex on DNA. Mol Cell. 57:1047–1058. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard

RE, Bonn T, Engström O, Ohman L, Greene GL, Gustafsson JA and

Carlquist M: Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the

oestrogen receptor. Nature. 389:753–758. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Heery DM, Kalkhoven E, Hoare S and Parker

MG: A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates

binding to nuclear receptors. Nature. 387:733–736. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Torchia J, Rose DW, Inostroza J, Kamei Y,

Westin S, Glass CK and Rosenfeld MG: The transcriptional

co-activator p/CIP binds CBP and mediates nuclear-receptor

function. Nature. 387:677–684. 1997. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kumar R, Betney R, Li J, Thompson EB and

McEwan IJ: Induced alpha-helix structure in AF1 of the androgen

receptor upon binding transcription factor TFIIF. Biochemistry.

43:3008–3013. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Bevan CL, Hoare S, Claessens F, Heery DM

and Parker MG: The AF1 and AF2 domains of the androgen receptor

interact with distinct regions of SRC1. Mol Cell Biol.

19:8383–8392. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Huang B, Omoto Y, Iwase H, Yamashita H,

Toyama T, Coombes RC, Filipovic A, Warner M and Gustafsson JÅ:

Differential expression of estrogen receptor alpha, beta1, and

beta2 in lobular and ductal breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

111:1933–1938. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Couse JF and Korach KS: Estrogen receptor

null mice: What have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr

Rev. 20:358–417. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Jia M, Dahlman-Wright K and Gustafsson JÅ:

Estrogen receptor alpha and beta in health and disease. Best Pract

Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 29:557–568. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Martin EC, Conger AK, Yan TJ, Hoang VT,

Miller DF, Buechlein A, Rusch DB, Nephew KP, Collins-Burow BM and

Burow ME: MicroRNA-335-5p and −3p synergize to inhibit estrogen

receptor alpha expression and promote tamoxifen resistance. FEBS

Lett. 591:382–392. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Santner SJ, Feil PD and Santen RJ: In situ

estrogen production via the estrone sulfatase pathway in breast

tumors: Relative importance versus the aromatase pathway. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 59:29–33. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Jordan VC: Antiestrogenic action of

raloxifene and tamoxifen: Today and tomorrow. J Natl Cancer Inst.

90:967–971. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Arpino G, Weiss H, Lee AV, Schiff R, De

Placido S, Osborne CK and Elledge RM: Estrogen receptor-positive,

progesterone receptor-negative breast cancer: Association with

growth factor receptor expression and tamoxifen resistance. J Natl

Cancer Inst. 97:1254–1261. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Horwitz KB, Koseki Y and McGuire WL:

Estrogen control of progesterone receptor in human breast cancer:

Role of estradiol and antiestrogen. Endocrinology. 103:1742–1751.

1978. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Dowsett M, Houghton J, Iden C, Salter J,

Farndon J, A'Hern R and Baum M: Estrogen receptor status,

progesterone receptor status, and HER2 status as biomarkers for

predicting response to endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol.

26:1814–1820. 2008.

|

|

59

|

Kumar R, Zakharov MN, Khan SH, Miki R,

Jang H, Toraldo G, Singh R, Bhasin S and Jasuja R: The dynamic

structure of the estrogen receptor. J Amino Acids. 2011:8125402011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Weihua Z, Andersson S, Cheng G, Simpson

ER, Warner M and Gustafsson JA: Update on estrogen signaling. FEBS

Lett. 546:17–24. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Flouriot G, Brand H, Denger S, Metivier R,

Kos M, Reid G, Sonntag-Buck V and Gannon F: Identification of a new

isoform of the human estrogen receptor-alpha (hER-alpha) that is

encoded by distinct transcripts and that is able to repress

hER-alpha activation function 1. EMBO J. 19:4688–4700. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Langley RE, Godsland IF, Kynaston H,

Clarke NW, Rosen SD, Morgan RC, Pollock P, Kockelbergh R, Lalani

EN, Dearnaley D, et al: Early hormonal data from a multicentre

phase II trial using transdermal oestrogen patches as first-line

hormonal therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic

prostate cancer. BJU Int. 102:442–445. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Lau KM and To KF: Importance of estrogenic

signaling and its mediated receptors in prostate cancer. Int J Mol

Sci. 17:14342016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Ricke WA, McPherson SJ, Bianco JJ, Cunha

GR, Wang Y and Risbridger GP: Prostatic hormonal carcinogenesis is

mediated by in situ estrogen production and estrogen receptor alpha

signaling. FASEB J. 22:1512–1520. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Olczak M, Orzechowska MJ, Bednarek AK and

Lipiński M: The transcriptomic profiles of ESR1 and MMP3 stratify

the risk of biochemical recurrence in primary prostate cancer

beyond clinical features. Int J Mol Sci. 24:83992023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Lin Q, Cao J, Du X, Yang K, Yang X, Liang

Z, Shi J and Zhang J: CYP1B1-catalyzed 4-OHE2 promotes the

castration resistance of prostate cancer stem cells by estrogen

receptor α-mediated IL6 activation. Cell Commun Signal. 20:312022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Reis LO, Zani EL and García-Perdomo HA:

Estrogen therapy in patients with prostate cancer: A contemporary

systematic review. Int Urol Nephrol. 50:993–1003. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Christoforou P, Christopoulos PF and

Koutsilieris M: The role of estrogen receptor β in prostate cancer.

Mol Med. 20:427–434. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Sieh W, Köbel M, Longacre TA, Bowtell DD,

deFazio A, Goodman MT, Høgdall E, Deen S, Wentzensen N, Moysich KB,

et al: Hormone-receptor expression and ovarian cancer survival: An

ovarian tumor tissue analysis consortium study. Lancet Oncol.

14:853–862. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Park SH, Cheung LWT, Wong AST and Leung

PCK: Estrogen regulates Snail and Slug in the down-regulation of

E-cadherin and induces metastatic potential of ovarian cancer cells

through estrogen receptor alpha. Mol Endocrinol. 22:2085–2098.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Chan KK, Leung TH, Chan DW, Wei N, Lau GT,

Liu SS, Siu MK and Ngan HY: Targeting estrogen receptor subtypes

(ERα and ERβ) with selective ER modulators in ovarian cancer. J

Endocrinol. 221:325–336. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Langdon SP, Herrington CS, Hollis RL and

Gourley C: Estrogen signaling and its potential as a target for

therapy in ovarian cancer. Cancers (Basel). 12:16472020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

He M, Yu W, Chang C, Miyamoto H, Liu X,

Jiang K and Yeh S: Estrogen receptor α promotes lung cancer cell

invasion via increase of and cross-talk with infiltrated

macrophages through the CCL2/CCR2/MMP9 and CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling

pathways. Mol Oncol. 14:1779–1799. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Siegel DA, Fedewa SA, Henley SJ, Pollack

LA and Jemal A: Proportion of never smokers among men and women

with lung cancer in 7 US States. JAMA Oncol. 7:302–304. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Hsu LH, Liu KJ, Tsai MF, Wu CR, Feng AC,

Chu NM and Kao SH: Estrogen adversely affects the prognosis of

patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 106:51–59. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Chlebowski RT, Schwartz AG, Wakelee H,

Anderson GL, Stefanick ML, Manson JE, Rodabough RJ, Chien JW,

Wactawski-Wende J, Gass M, et al: Oestrogen plus progestin and lung

cancer in postmenopausal women (Women's Health Initiative trial): A

post-hoc analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet.

374:1243–1251. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Zhou J, Teng R, Xu C, Wang Q, Guo J, Xu C,

Li Z, Xie S, Shen J and Wang L: Overexpression of ERα inhibits

proliferation and invasion of MKN28 gastric cancer cells by

suppressing β-catenin. Oncol Rep. 30:1622–1630. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Takano N, Iizuka N, Hazama S, Yoshino S,

Tangoku A and Oka M: Expression of estrogen receptor-alpha and

-beta mRNAs in human gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 176:129–135.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Tang W, Liu R, Yan Y, Pan X, Wang M, Han

X, Ren H and Zhang Z: Expression of estrogen receptors and androgen

receptor and their clinical significance in gastric cancer.

Oncotarget. 8:40765–40777. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Chen P, Li B and Ou-Yang L: Role of

estrogen receptors in health and disease. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 13:8390052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Chen J and Iverson D: Estrogen in

obesity-associated colon cancer: Friend or foe? Protecting

postmenopausal women but promoting late-stage colon cancer. Cancer

Causes Control. 23:1767–1773. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Jiang H, Teng R, Wang Q, Zhang X, Wang H,

Wang Z, Cao J and Teng L: Transcriptional analysis of estrogen

receptor alpha variant mRNAs in colorectal cancers and their

matched normal colorectal tissues. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol.

112:20–24. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Dai B, Geng L, Yu Y, Sui C, Xie F, Shen W,

Zheng T and Yang J: Methylation patterns of estrogen receptor α

promoter correlate with estrogen receptor α expression and

clinicopathological factors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Biol

Med (Maywood). 239:883–890. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Hou J, Xu J, Jiang R, Wang Y, Chen C, Deng

L, Huang X, Wang X and Sun B: Estrogen-sensitive PTPRO expression

represses hepatocellular carcinoma progression by control of STAT3.

Hepatology. 57:678–688. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Iyer JK, Kalra M, Kaul A, Payton ME and

Kaul R: Estrogen receptor expression in chronic hepatitis C and

hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol.

23:6802–6816. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M,

Nilsson S and Gustafsson JA: Cloning of a novel receptor expressed

in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 93:5925–5930.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Mal R, Magner A, David J, Datta J,

Vallabhaneni M, Kassem M, Manouchehri J, Willingham N, Stover D,

Vandeusen J, et al: Estrogen receptor beta (ERβ): A ligand

activated tumor suppressor. Front Oncol. 10:5873862020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Lewandowski S, Kalita K and Kaczmarek L:

Estrogen receptor beta. Potential functional significance of a

variety of mRNA isoforms. FEBS Lett. 524:1–5. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Hua H, Zhang H, Kong Q and Jiang Y:

Mechanisms for estrogen receptor expression in human cancer. Exp

Hematol Oncol. 7:242018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Haldosén LA, Zhao C and Dahlman-Wright K:

Estrogen receptor beta in breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol.

382:665–672. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Dalal H, Dahlgren M, Gladchuk S, Brueffer

C, Gruvberger-Saal SK and Saal LH: Clinical associations of ESR2

(estrogen receptor beta) expression across thousands of primary

breast tumors. Sci Rep. 12:46962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Wang J, Zhang C, Chen K, Tang H, Tang J,

Song C and Xie X: ERβ1 inversely correlates with PTEN/PI3K/AKT

pathway and predicts a favorable prognosis in triple-negative

breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 152:255–269. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Grober OM, Mutarelli M, Giurato G, Ravo M,

Cicatiello L, De Filippo MR, Ferraro L, Nassa G, Papa MF, Paris O,

et al: Global analysis of estrogen receptor beta binding to breast

cancer cell genome reveals an extensive interplay with estrogen

receptor alpha for target gene regulation. BMC Genomics. 12:362011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Hurtado A, Pinós T, Barbosa-Desongles A,

López-Avilés S, Barquinero J, Petriz J, Santamaria-Martínez A,

Morote J, de Torres I, Bellmunt J, et al: Estrogen receptor beta

displays cell cycle-dependent expression and regulates the G1 phase

through a non-genomic mechanism in prostate carcinoma cells. Cell

Oncol. 30:349–365. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Hwang NM and Stabile LP: Estrogen receptor

ß in cancer: To ß(e) or not to ß(e)? Endocrinology.

162:bqab1622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Mak P, Leav I, Pursell B, Bae D, Yang X,

Taglienti CA, Gouvin LM, Sharma VM and Mercurio AM: ERbeta impedes

prostate cancer EMT by destabilizing HIF-1alpha and inhibiting

VEGF-mediated snail nuclear localization: Implications for Gleason

grading. Cancer Cell. 17:319–332. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Mak P, Chang C, Pursell B and Mercurio AM:

Estrogen receptor β sustains epithelial differentiation by

regulating prolyl hydroxylase 2 transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 110:4708–4713. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Lim W, Cho J, Kwon HY, Park Y, Rhyu MR and

Lee Y: Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha activates and is inhibited

by unoccupied estrogen receptor beta. FEBS Lett. 583:1314–1318.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Chaurasiya S, Widmann S, Botero C, Lin CY,

Gustafsson JÅ and Strom AM: Estrogen receptor β exerts tumor