Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most malignant

primary human brain tumor. Tumors are characterized by a high

proliferation rate and chemoresistance (1).

Although the combination of radiotherapy and

chemotherapy has progressed after surgical resection, the 5-year

survival rate of WHO grade IV glioblastoma is still lower than 5%

(2,3).

Although significant progress has been made in understanding the

molecular status of this type of tumor, there is still a need for

new and effective therapeutic approaches (4–6).

Epithelial membrane protein 1 (EMP1) is a member of

the EMP family that has been implicated as a cell junction protein

on the plasma membrane (7). However,

little is known about its specific functions and mechanisms.

Recently, several members of the EMP family have been indicated to

participate in cancer progression. EMP1 has been revealed to be a

novel poor prognostic factor in pediatric leukemia and gastric

carcinoma by regulating cell proliferation, migration and invasion,

and was demonstrated to be involved in gefitinib resistance in lung

cancer (8,9). EMP1 was also identified as a novel

MYC-interacting gene with cancer-related functions in GBM (10). However, the biological role of EMP1 in

GBM remains unclear.

To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to

determine the important role of EMP1 in GBM. In the present study,

it was revealed that knockdown of EMP1 inhibited GBM cell

proliferation, migration and invasion. In addition, it was

determined that EMP1 is an independent predictor of poor prognosis

in GBM patients. To sum up, our data indicated that EMP1 is a

potential therapeutic target for the treatment of GBM.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

All animal procedures were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Shandong

University (Jinan, China).

Database searches

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, http://cancergenome.nih.gov/), Rembrandt (http://www.betastasis.com/glioma/rembrandt/), and the

Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA, http://www.cgga.org.cn/) were mined for relevant

molecular data.

Cell lines and cultures

Human glioblastoma cell lines U251 (cat. no.

TCHu58), A172 (cat. no. TCHu171) and human glioblastoma of unknown

origin cell line U87MG (cat. no. TCHu138, authentication was

performed using STR Multi-Amplification Kit in Guangzhou Cellcook

Biotech Co., Ltd.) were purchased from the Chinese Academy of

Sciences Cell Bank (Shanghai, China). Human fibroblast glioblastoma

cell line T98, primary human GBM biopsy xenograft propagated tumor

cells P3 and normal human astrocytes were kindly provided by

Professor Rolf Bjerkvig, University of Bergen (Bergen, Norway).

Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM;

cat. no. SH30022.01B; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (cat. no. 10082147; Hyclone; GE

Healthcare Life Sciences) in 5% CO2 in a humidified

incubator at 37°C.

Immunohistochemical staining

Samples were fixed in 4% formalin at 20°C for 24 h,

paraffin-embedded and sectioned (4 µm). After dewaxing and

rehydration, sections were incubated with 0.01 M citrate buffer at

95°C for 20 min for antigen retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase

activity and non-specific antigen were blocked with 3% hydrogen

peroxide and 10% normal goat serum (both from ZSGB-Bio; OriGene

Technologies, Inc.), respectively, followed by primary antibody

(EMP1; 1:100; cat. no. 63735; LifeSpan BioSciences) overnight at

4°C. Sections were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS),

treated with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (cat. no. 1:200;

cat. no. PV-9000; ZSGB-BIO), visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine

(DAB; both from ZSGB-Bio; OriGene Technologies, Inc.), and

hematoxylin (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Normal mouse

serum served as a negative control.

shRNA transfections

Short hairpin (sh)-EMP1 (#1: GTT TGT TAG CAC CAT TGC

CAA TGT TTC AAG AGA ACA TTG GCA ATG GTG CTA ACA AAT TTT TT; #2: GGT

CTT TGG AAA AAC TGT ACC AAT TCA AGA GAT TGG TAC AGT TTT TCC AAA GAC

CTT TTT T; #3: GCC AGT GAA GAT G CCC TCA AGA CAT TCA AGA GAT GTC

TTG AGG GCA TCT TCA CTG GTT TTT T), were conjugated in the

lentiviral vector of pLKO.1 with a puromycin resistant region

(GenePharma). U87MG and P3 GBM cells were plated and infected with

lentiviruses expressing sh-EMP1 for 24 h, followed by puromycin

selection (2 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Western blotting

was performed to verify knockdown efficiency and cells were

allocated for different assays.

Cell viability assays

Cell viability was assessed using Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8; cat. no. CK04-500; Dojindo Molecular Technologies,

Inc.). Cells (1.0×104 cells/well) were seeded into

96-well plates and incubated at 37°C overnight. After the desired

treatment, the cells were incubated with 10 µl of CKCK-8 in 100 µl

of serum-free DMEM for a further 4 h at 37°C. The absorbance at 450

nm was measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.).

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates (20 µg protein) were subjected to

western blot analysis, according to previously described protocols

(11). Membranes were incubated with

the following antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology: AKT

(dilutions 1:1,000, cat. no. 9272), p-Akt (Ser473, dilution

1:1,000; cat. no. 4060), mTOR (dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. 2972),

p-mTOR (Ser2448, dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. 2974), GAPDH (dilution

1:1,000; cat. no. 5174). Additional antibody was EMP1 (dilution

1:1,000; cat. no. 63735; LifeSpan BioSciences).

Cell migration and invasion

assays

The wound healing assay was used to assess cell

migration. U87MG and P3 GBM cells were seeded into 6-well flat

bottom plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. The cell-free space

was created by scraping with a 200-µl pipette tip. Wound closure

areas were monitored at different time-points under a microscope

and quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of

Health). Cell invasion assays were performed in uncoated and

Matrigel-coated Transwell chambers (8-µm pore size inserts;

Corning, Inc.). Cells (2×104) in medium containing 1%

FBS (200 µl) were seeded in the top chamber. The lower chamber was

filled with medium containing 30% FBS (600 µl). The cells that

invaded the lower surface were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

(Solarbio; Beijing, China) at 20°C for 15 min, stained with 0.1%

crystal violet (Solarbio) at 20°C for 15 min and counted under a

bright field microscope. Images were captured from 5 random fields

in each well and the number of cells was determined using Kodak MI

SE 5.0 software (Carestream Health). Each experiment was repeated

three times.

Intracranial xenograft model

Athymic mice (male; 4 weeks old; 20–30 g) were

provided by Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. The mice were

anesthetized with 5% chloral hydrate and secured on a stereotactic

frame. A longitudinal incision was made in the scalp and a 1-mm

diameter hole was drilled 2.5 mm lateral to the bregma.

Luciferase-stable P3 GBM cells (2×105) in 20 µl of

serum-free DMEM were implanted 2.5 mm into the right striatum using

a Hamilton syringe. Mice were monitored by bioluminescence imaging

every week. Briefly, mice were injected with 100 mg of luciferin

(Caliper; PerkinElmer, Inc.) while anesthetized with 3% isoflurane,

followed by a cooled charge-coupled device camera (IVIS-200;

Xenogen; Alameda, CA, USA). Bioluminescence values of tumors were

quantitated using the Living Image 2.5 software package (Xenogen

Corp.). Mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation and

dislocation of neck after 30 days or when they developed

neurological symptoms such as rotational behavior, reduced activity

or displayed grooming and dome head. The brains were extracted,

perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and coronally sectioned

for immunohistochemistry assays.

Statistical analysis

Three independent experiments were performed, and

results were expressed as the mean ± the standard deviation (SD).

Data were compared using paired Student t-tests or one-way ANOVA

followed by Bonferroni tests in GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad

Software, Inc.). P-values determined from different comparisons

<0.05 were considered statistically significant and are

indicated as follows: *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Results

EMP1 expression is positively

correlated with tumor grade

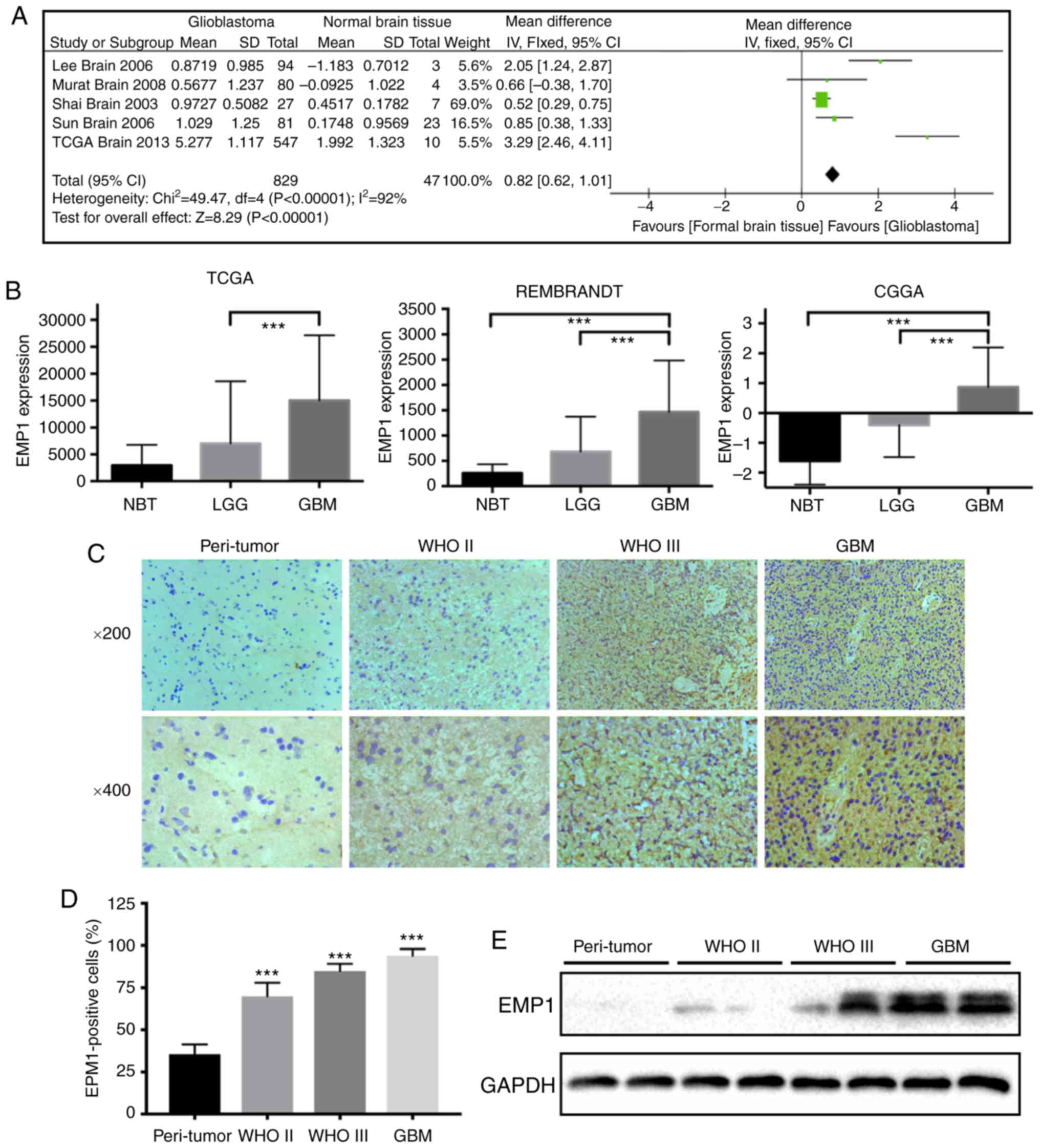

To begin, to determine whether EMP1 was

differentially expressed between glioblastoma and normal tissues,

microarray data from patient samples were extensively examined in

the Oncomine database. A meta-analysis of five independent

glioblastoma data sets including 829 human glioblastoma samples and

47 normal brain tissues revealed that EMP1 was significantly and

consistently present in glioblastoma in all data sets (Fig. 1A). To further verify the level of EMP1

in normal brain tissues and different grade glioma tissues, the

publicly available databases, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA),

Rembrandt, and the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) were

systematically retrieved and a relatively higher mRNA level of EMP1

was revealed in high grade gliomas compared to low grade gliomas

(P<0.01; Fig. 1B).

Immunohistochemistry results revealed that increased EMP1 levels

were associated with increased glioma grade. EMP1 was highly

expressed in grade II/III astrocytoma and glioblastoma (P<0.01),

whereas staining was weak or absent in peri-tumor tissues (Fig. 1C and D). Western blotting results

corroborated these results. EMP1 protein levels were increased in

glioma cases relative to peri-tumor tissues (Fig. 1E). Collectively, these results

demonstrated that EMP1 levels were increased in glioma compared to

normal brain tissues.

EMP1 expression is inversely

associated with glioblastoma patient prognosis

The differences in expression levels of EMP1 in

glioma and normal brain tissues prompted us to further investigate

whether EMP1 can be used as a prognostic marker in glioma patients.

Data from the TCGA, Rembrandt, and CGGA databases was used to

determine the relationship between EMP1 levels and overall survival

(OS) in glioma patients. Each sample was classified as EMP1-high

expression if the signal was above the median expression for the

population. These data revealed significant differences in OS and

progression-free survival (PFS) between glioma patients with low

EMP1 expression and those with high expression (Fig. 2).

Pathway analysis of EMP1 and

co-regulated genes

Next, to further understand the biological

implications of EMP1 in gliomas, correlation analysis of EMP1

expression in whole genome gene profiling was performed in TCGA.

The results revealed that 5,604 genes were correlated with EMP1

expression in TCGA database (P<0.01; Fig. 3A). As illustrated in the volcano plot

and heatmaps, these significant correlated genes were separated

into positively correlated and negatively correlated genes

(Fig. 3B and C). Subsequently, GO

analysis revealed that EMP1 positively-correlated genes were

strongly associated with biological processes including positive

regulation of cell proliferation, negative regulation of apoptotic

process, cell adhesion and extracellular matrix organization

(Fig. 3D). In KEGG analysis,

EMP1-correlated genes were enriched in pathways in cancer,

especially in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (Fig. 3D).

Knockdown of EMP1 inhibits

proliferation, migration and invasion in glioma cells in vitro

To determine the biological roles in glioma, the

expression level of EMP1 was first verified in several glioma cell

lines. Western blots results confirmed that the expression levels

of EMP1 protein were increased in several glioma cell lines,

especially in P3 GBM, which was derived from a primary GBM through

orthotopic passage in mice (12–14), and

U87MG cells (Fig. 4A). shRNA

targeting EMP1 lentiviral constructs were designed for stable

knockdown of expression. EMP1 protein levels in U87MG and P3 GBM

cells were significantly downregulated after infection with three

different shRNAs against EMP1 compared to NC constructs, especially

sh-EMP1-2 (Fig. 4B). Therefore, this

shRNA was selected for the subsequent functional assays.

It was then determined whether EMP1 knockdown may be

effective against GBM, using the cell viability assay, CCK-8.

Knockdown of EMP1 led to significant decreases in cell viability in

both U87MG and P3 GBM cells (P<0.05; Fig. 4C). Having observed a marked change in

cell morphology and retraction of pseudopodia after knockdown of

EMP1, a wound healing assay was used to examine whether knockdown

of EMP1 affected migration in GBM cells. Knockdown of EMP1 led to a

significant lower migratory rate both in U87MG and P3 GBM cells

(P<0.01; Fig. 4D and E). Transwell

analysis was further applied to assess the inhibitory effect of

EMP1 knockdown on cell invasion. In order to mimic the

extracellular matrix around glioma, U87GBM and P3 GBM cells were

plated in the upper chambers of a Transwell system coated with

Matrigel. The results revealed that the invasive ability of GBM

cell was significantly decreased after knockdown of EMP1 (Fig. 4F and G).

EMP1 promotes human glioma progression

through activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

It is well known that abnormal activation of the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway promotes tumorigenesis, and in KEGG

analysis, EMP1-correlated genes were enriched in the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway (Fig. 3D).

Therefore, phosphorylation status of AKT and mTOR proteins after

knockdown of EMP1 was examined by western blotting to determine

whether the observed responses could be due to a decrease in

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Phosphorylated AKT and mTOR decreased

compared to sh-NC following knockdown of EMP1 in modified cells,

demonstrating that the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway was

inhibited after EMP1 knockdown (Fig.

5A). After being treated simultaneously with the novel AKT

activator SC79, the activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling

pathway in GBM cells was partially restored. SC79 increased

phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR in EMP1-knockdown GBM cells, and

therefore further confirmed PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling as a molecular

target for EMP1 knockdown of GBM growth (Fig. 5B). CCK-8 and Transwell invasion assays

were repeated to assess whether SC79 could restore proliferation

and invasion in EMP1-knockdown GBM cells. The results demonstrated

that SC79 increased proliferation (~50 vs. 70%; sh-EMP1 vs.

sh-EMP1+SC79; P<0.05) and invasion (~50 vs. 90%; sh-EMP1 vs.

sh-EMP1+SC79; P<0.05) in EMP1-knockdown GBM cells (Fig. 5C-E).

EMP1 enhances growth of GBM cells in

vivo

Considering the heterogeneity of GBM, P3 GBM, which

is an in vivo-propagated primary GBM tumor cell line, was

applied to investigate EMP1 function. Athymic nude mice

(n=10) were implanted with luciferase-stable P3 cells in an

intracranial tumor model and tumor growth was monitored over time

using bioluminescence values. The results demonstrated that

knockdown of EMP1 significantly reduced tumor growth

(~35×108 vs. ~20×108 photons/sec, sh-NC vs.

sh-EMP1; Fig. 6A and B). Kaplan-Meier

analysis of the survival data demonstrated a statistically

significant difference between sh-NC and sh-EMP1 mice (P<0.05,

~29 vs. >32 days, sh-NC vs. sh-EMP1; Fig. 6C). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was

performed on tissue sections from animals to examine proliferation

and invasion. Ki-67, a marker for proliferation, MMP2 and MMP9,

markers for invasion were decreased after EMP1 knockdown (Fig. 6D).

Discussion

Molecular-targeting therapy has become a promising

therapeutic strategy for extending the survival time of cancer

patients. Therefore, identifying novel therapeutic targets is

critical for the design of more effective tumor specific strategies

(15). Recently, several members of

the EMP family have been indicated to participate in cancer

progression (16–19). For instance, it has been reported that

EMP1 is an oncogene of resistance to gefitinib in lung cancer, and

it contributes to prednisolone resistance in patients with acute

lymphoblastic leukemia. EMP2 was reported to be a biomarker in

endometrial and ovarian cancer patients. Overexpression of EMP3 in

breast cancer is significantly associated with high expression

level of HER-2 which is one of the most important biomarkers of

progression and metastasis-free survival for urothelial carcinoma

of the upper urinary tract patients (19). Ramnarain et al revealed that

the expression of EGFRvIII resulted in upregulation of a small

group of genes including EMP1 in glioma cell lines (20). Bredel et al revealed that EMP1

is one of the novel MYC-responsive genes in gliomas (10). These studies indicated that EMP1 may

be an oncogene in GBM, however, the biological role and underlying

mechanism of EMP1 in GBM remains unclear.

In the present study, EMP1 was identified as a

potential target of GBM molecular-targeting therapy. According to

the mRNA microarray of TCGA, Rembrandt and CGGA, it was revealed

that the mRNA level of EMP1 was increased in glioma compared to

normal brain tissues. The IHC and western blot results of GBM or

normal brain tissues further verified this view. Moreover, glioma

patients with low EMP1 expression level had improved overall

survival. Collectively, these data indicated that EMP1 could be

associated with the malignancy of GBM and may serve as a novel

prognostic indicator in clinical practice.

Abnormal cell proliferation, migration and invasion

are hallmark characteristics of human gliomas. Many genetic changes

lead to uncontrolled growth through dysregulation of proteins

directly involved in cell cycle progression and cell invasion

(21). GO analyses revealed that

EMP1-assosiated genes exhibited significant enrichment mainly in

processes related to cell proliferation, adhesion and extracellular

matrix organization. The in vitro and in vivo data

supported this analysis. EMP1 knockdown decreased the

proliferation, migration and invasion in glioma cells and reduced

tumor growth in orthotopic xenografts. Inhibition of cell

proliferation can be the cause of senescence, apoptosis and

autophagic cell death. Recent studies revealed that EMP1 also

participated in nasopharyngeal and gastric cancer cell apoptosis

(9,22). Therefore, the cross-talk between EMP1

and senescence, apoptosis and autophagic cell death requires

further exploration.

Glioma progression is a dynamic process in which the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is a key event driving abnormal

proliferation, differentiation and invasion of tumor cells

(23). Mutations in the PTEN

tumor-suppressor gene, a key regulator of the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway, lead to misaligned pathways in tumor cells. Results of

KEGG analysis revealed that EMP1-associated upregulated genes were

mainly enriched in the PI3K-AKT pathway. In the present in

vitro study, the expression levels of p-AKT and p-mTOR were

both decreased in EMP1-knockdown GBM cells. However, in the

presence of an AKT activator, SC79, p-AKT and p-mTOR levels as well

as functional activities including proliferation, migration, and

invasion were partially restored. In conclusion, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway provides a molecular basis for the inhibition of

tumor growth through EMP1 knockdown. However, the precise molecular

mechanisms of the cross-talk between EMP1 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling in gliomas require further investigation.

In summary, EMP1 facilitates proliferation,

migration and invasion of GBM cells both in vitro and in

vivo potentially by activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling

pathway. These results raise the possibility that targeting EMP1

may represent a promising strategy for the treatment of GBM.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Rolf Bjerkvig for

providing human fibroblast glioblastoma cell line T98, primary

human GBM biopsy xenograft propagated tumor cells P3 and normal

human astrocytes, and Dr Janice Nigro for critical comments on the

manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural

Science Foundation of China Grants (81572487, 81402060 and

81472353), the Special Foundation for Taishan Scholars (ts20110814,

tshw201502056 and tsqn20161067), the Department of Science and

Technology of Shandong Province (2015ZDXX0801A01 and 2014kjhm0101),

the Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation (ZR2014HM074), the

Shandong Provincial Outstanding Medical Academic Professional

Program, the Health and Family Planning Commission of Shandong

province (2017WS673), the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong

University (2016JC019), the University of Bergen and the K.G.

Jebsen Brain Tumor Research Centre.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are

available from the corresponding author upon reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

XL and PZ conceived and designed the experiments;

LM, ZJ, JW, NY, QQ, WZ and ZF performed the experiments; LM and ZJ

analyzed the data; WL, QZ, BH, AC and DZ contributed to the

reagents/materials/analysis tools. All authors were involved in the

writing of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal procedures were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Shandong

University (Jinan, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ricard D, Idbaih A, Ducray F, Lahutte M,

Hoang-Xuan K and Delattre JY: Primary brain tumours in adults.

Lancet. 379:1984–1996. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kalpathy-Cramer J, Gerstner ER, Emblem KE,

Andronesi OC and Rosen B: Advanced magnetic resonance imaging of

the physical processes in human glioblastoma. Cancer Res.

74:4622–4637. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

van den Bent M, Chinot OL and Cairncross

JG: Recent developments in the molecular characterization and

treatment of oligodendroglial tumors. Neuro Oncol. 5:128–138. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Garrido W, Rocha JD, Jaramillo C,

Fernandez K, Oyarzun C, San Martin R and Quezada C: Chemoresistance

in high-grade gliomas: Relevance of adenosine signalling in

stem-like cells of glioblastoma multiforme. Curr Drug Targets.

15:931–942. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lee CY: Strategies of temozolomide in

future glioblastoma treatment. Onco Targets Ther. 10:265–270. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Uribe D, Torres A, Rocha JD, Niechi I,

Oyarzún C, Sobrevia L, San Martín R and Quezada C: Multidrug

resistance in glioblastoma stem-like cells: Role of the hypoxic

microenvironment and adenosine signaling. Mol Aspects Med.

55:140–151. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bangsow T, Baumann E, Bangsow C, Jaeger

MH, Pelzer B, Gruhn P, Wolf S, von Melchner H and Stanimirovic DB:

The epithelial membrane protein 1 is a novel tight junction protein

of the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 28:1249–1260.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Aries IM, Jerchel IS, van den Dungen RE,

van den Berk LC, Boer JM, Horstmann MA, Escherich G, Pieters R and

den Boer ML: EMP1, a novel poor prognostic factor in pediatric

leukemia regulates prednisolone resistance, cell proliferation,

migration and adhesion. Leukemia. 28:1828–1837. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sun G, Zhao G, Lu Y, Wang Y and Yang C:

Association of EMP1 with gastric carcinoma invasion, survival and

prognosis. Int J Oncol. 45:1091–1098. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bredel M, Bredel C, Juric D, Harsh GR,

Vogel H, Recht LD and Sikic BI: Functional network analysis reveals

extended gliomagenesis pathway maps and three novel MYC-interacting

genes in human gliomas. Cancer Res. 65:8679–8689. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang J, Qi Q, Feng Z, Zhang X, Huang B,

Chen A, Prestegarden L, Li X and Wang J: Berberine induces

autophagy in glioblastoma by targeting the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1-pathway.

Oncotarget. 7:66944–66958. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Fack F, Espedal H, Keunen O, Golebiewska

A, Obad N, Harter PN, Mittelbronn M, Bähr O, Weyerbrock A, Stuhr L,

et al: Bevacizumab treatment induces metabolic adaptation toward

anaerobic metabolism in glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol.

129:115–131. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fack F, Tardito S, Hochart G, Oudin A,

Zheng L, Fritah S, Golebiewska A, Nazarov PV, Bernard A, Hau AC, et

al: Altered metabolic landscape in IDH-mutant gliomas affects

phospholipid, energy, and oxidative stress pathways. EMBO Mol Med.

9:1681–1695. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tardito S, Oudin A, Ahmed SU, Fack F,

Keunen O, Zheng L, Miletic H, Sakariassen PØ, Weinstock A, Wagner

A, et al: Glutamine synthetase activity fuels nucleotide

biosynthesis and supports growth of glutamine-restricted

glioblastoma. Nat Cell Biol. 17:1556–1568. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Rajesh Y, Pal I, Banik P, Chakraborty S,

Borkar SA, Dey G, Mukherjee A and Mandal M: Insights into molecular

therapy of glioma: Current challenges and next generation

blueprint. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 38:591–613. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hsieh YH, Hsieh SC, Lee CH, Yang SF, Cheng

CW, Tang MJ, Lin CL, Lin CL and Chou RH: Targeting EMP3 suppresses

proliferation and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells

through inactivation of PI3K/Akt pathway. Oncotarget.

6:34859–34874. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lai S, Wang G, Cao X, Li Z, Hu J and Wang

J: EMP-1 promotes tumorigenesis of NSCLC through PI3K/AKT pathway.

J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 32:834–838. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang HT, Kong JP, Ding F, Wang XQ, Wang

MR, Liu LX, Wu M and Liu ZH: Analysis of gene expression profile

induced by EMP-1 in esophageal cancer cells using cDNA Microarray.

World J Gastroenterol. 9:392–398. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wang YW, Cheng HL, Ding YR, Chou LH and

Chow NH: EMP1, EMP 2, and EMP3 as novel therapeutic targets in

human cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1868:199–211. 2017.

|

|

20

|

Ramnarain DB, Park S, Lee DY, Hatanpaa KJ,

Scoggin SO, Otu H, Libermann TA, Raisanen JM, Ashfaq R, Wong ET, et

al: Differential gene expression analysis reveals generation of an

autocrine loop by a mutant epidermal growth factor receptor in

glioma cells. Cancer Res. 66:867–874. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sun GG, Lu YF, Fu ZZ, Cheng YJ and Hu WN:

EMP1 inhibits nasopharyngeal cancer cell growth and metastasis

through induction apoptosis and angiogenesis. Tumour Biol.

35:3185–3193. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Manning BD and Toker A: AKT/PKB signaling:

Navigating the network. Cell. 169:381–405. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|