Introduction

Several studies have reported on the concentration

of gingerols in fresh ginger (Zingiber officinale var.

Roscoe) rhizomes, for instance, the methanol extract of Z.

officinale var. Roscoe rhizome cultivated in Hawaii contained

6-, 8- and 10-gingerol at concentrations of 2,100, 288 and 533

µg/g, respectively (1); the methylene

chloride extract of Z. officinale var. Roscoe rhizome

cultivated in America yielded 880, 93 and 120 µg/g of 6-, 8- and

10-gingerol, respectively (2); and

the fresh rhizome of Z. officinale var. Roscoe cultivated in

Taiwan contained 806 µg/g of 6-gingerol (3). Furthermore, phytochemical screening of

the chloroform extract of Z. officinale var. Roscoe rhizome

cultivated in Pakistan has given positive results on the presence

of alkaloid, phlobotannins, flavonoids, glycosides, saponins,

tannin and terpenoids, while indicating the absence of steroids

(4). Alkaloids, carbohydrates,

glycosides, proteins, saponins, steroids, flavonoids and terpenoids

has been identified in Z. officinale var. Roscoe, and

phenolic compounds including gingerol and shogaol (5–7), while

reducing sugars, tannins, oils and acid compounds were absent.

Similarly, results of proximate analysis of the rhizome have

indicated mostly carbohydrates (71.46%) and crude protein (8.83%)

with a small crude fibre content of 0.92% (5).

A comparative study of Z. officinale var.

Roscoe pulp and peel demonstrated that the hydro-alcoholic extract

of the peel exhibited marked inhibition of the growth of colon

cancer cells on MTT assay, while the pulp extract exhibited high

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities, allegedly due to

differing polyphenolic content and lipophilic composition (8). Data on the effects of Z.

officinale var. Roscoe have been reviewed, and it has been

concluded that the rhizome of this plant has potential as an

anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative source, nonetheless further

research has been suggested prior to confirming its efficacy

(9). The medicinal properties of

Z. officinale var. Roscoe may be due to the presence of

gingerol, paradol and shogaols, among other compounds (10).

Gingerols are homologues of

1-(3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-keto-5-hydroxyhexane, shogaols are

dehydration products of the gingerols, and paradols are β-ketone

hydroxyl deoxygenation products of gingerols (11). In previous studies Z.

officinale var. Roscoe has exhibited anti-inflammatory activity

(8,12–16).

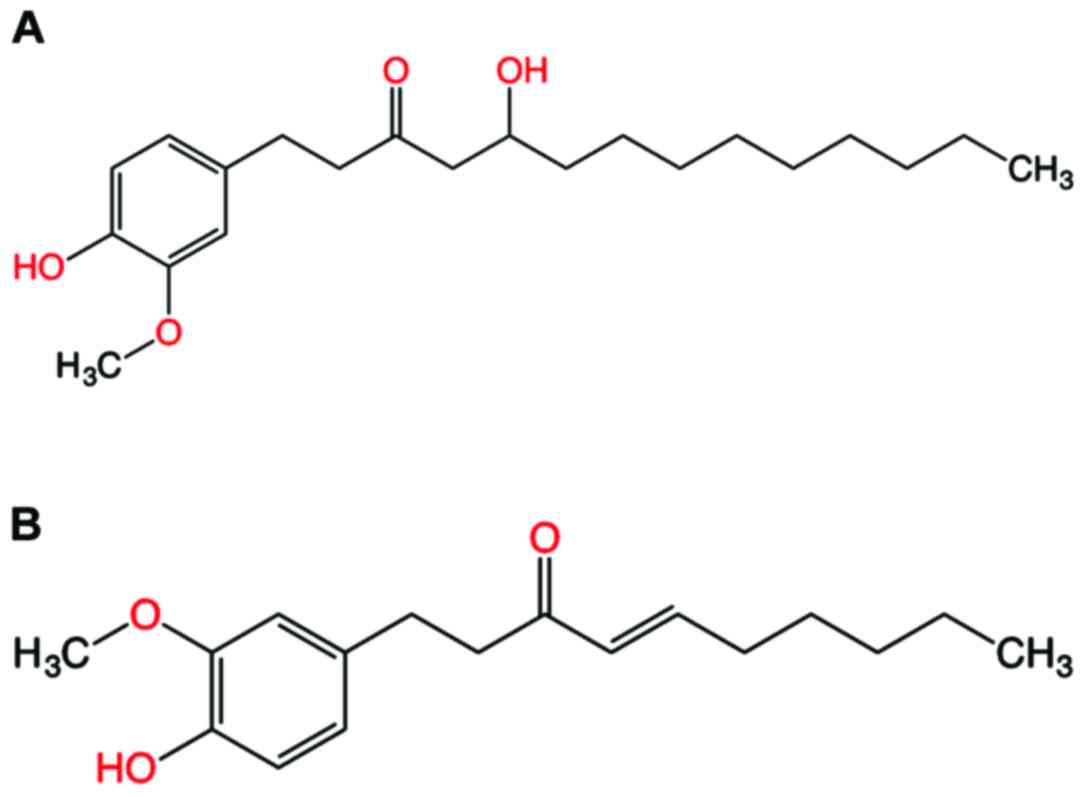

10-gingerol (Fig. 1A) has been

reported to exhibit the highest anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant

activities compared with those of other gingerols (17). Other studies on 6-gingerol have

confirmed its inhibition of nitric oxide production in activated

J774.1 mouse macrophages and prevention of peroxynitrite-induced

oxidation and nitration reactions (18). This compound may also inhibit

cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 expression by blocking the activation of p38

mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κB in phorbol

ester-stimulated mouse skin (19).

However, studies on the effects of red ginger (Z. officinale

var. Rubrum) are limited.

Previous study by Fikri et al (20) concluded that the hot water extract of

Z. officinale var. Rubrum rhizome inhibited the rate of

prostaglandin production in vitro. Furthermore, a

computational study of gingerol and shogaol against COX enzymes

reported that 6-gingerol and 6-shogaol were preferential COX-2

inhibitors and therefore potential candidates for development into

anti-inflammatory drugs (21).

Pharmacokinetic studies of the dry extract of ginger rhizomes (at

doses of 100 mg to 2 g) in the plasma of healthy American

volunteers have been conducted (22,23).

However, there is a lack of reports on red ginger. Thus, the

present work studied the pharmacokinetics of 10-gingerol (Fig. 1A) and 6-shogaol (Fig. 1B) in the plasma of healthy Indonesian

volunteers treated with a single dose (2 g) of red ginger

suspension. The aims of this study were to: i) Determine if red

ginger suspension is absorbed and biotransformed in humans; and ii)

assess the human pharmacokinetics of 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol.

Materials and methods

Instruments

Instruments used in the study were a liquid

chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) XEVO-QTOF MS

(Waters-MassLynx 4.1 SCN719; PT Kromtekindo Utama, Jakarta,

Indonesia) equipped with an RP-C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm), a

UV-visible double beam spectrophotometer (Specord 200; Analitik

Jena AG, Jena, Germany), a digital analytical balance [Ohaus

Pioneer; Ohaus Instruments (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China],

an Eppendorf Centrifuge 5424 R, a vortex mixer (Cole-Parmer, Vernon

Hills, IL, USA), a dipotassium ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid

(K2EDTA) tube (BD Vacutainer; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ,

USA) and chemical glasswares.

Chemicals and plant materials

10-gingerol of standard 98% purity (Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany; CAS no. 23513-15-7) and 6-shogaol

of standard 98% purity (Sigma-Aldrich; CAS no. 555-66-8) were

purchased from Quartiz Indonesia (PT Indogen Intertama, Jakarta,

Indonesia); methanol hypergrade for LC-MS (LiChrosolv®;

CAS no. 67-56-1) and acetonitrile gradient grade for liquid

chromatography (LiChrosolv® CAS no. 75-05-08) were

purchased from the Central Laboratory of Padjadjaran University

(Jatinangor, West Java, Indonesia); and 1 kg of fresh rhizome of

Z. officinale var. Rubrum was purchased from the Research

Institute for Spices and Medicinal Plants (Balittro) Manoko Lembang

(Bandung, Indonesia). The fresh rhizome was taxonomically

identified at the Laboratory of Plant Taxonomy, Department of

Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Padjadjaran

University, and the voucher specimen (no. 415/HB/08/2017) was

retained in our laboratory for future reference.

Preparation of red ginger (Zingiber

officinale var. Rubrum) suspension

The 1 kg of fresh rhizome of Z. officinale

var. Rubrum was thin-sliced (1–2 mm) and dried in a dehydrator at

50°C for 4 h. The dried rhizome was ground and each portion per

subject contained 2 g of the powder dissolved in 15 ml hot

distilled water (70°C).

Identification of 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol in Z. officinale var. Rubrum suspension

Identification of 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol in Z.

officinale var. Rubrum suspension was performed by dissolving

the suspension in 15 ml methanol hypergrade. The mixture was

vortexed and centrifuged at 20,440 × g at room temperature for 15

min. The supernatant was scanned at 200–380 nm in a double beam UV

spectrophotometer against the methanol hypergrade its maximum

wavelength (λmax) was compared with those of 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol.

Preparation of 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol standard solutions

A total of 2.5 mg of each of the 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol standards was dissolved in 100 ml methanol hypergrade in

a volumetric flask (25 µg/ml). The solutions were scanned at

200–380 nm in the double beam UV spectrophotometer against the

methanol hypergrade to obtain the λmax's of 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol. Various concentrations were prepared by diluting the

standard solution (Tables I and

II) (24).

| Table I.Preparation of 10-gingerol standard

solutions. |

Table I.

Preparation of 10-gingerol standard

solutions.

| Blank plasma, µl | 10-gingerol, µl | Acetonitrile, µl | Final concentration,

ng/ml |

|---|

| 200 | – | 800.0 | Blank |

| 200 |

2.5 | 797.5 |

2.5 |

| 200 |

5.0 | 795.0 |

5.0 |

| 200 | 10.0 | 790.0 | 10.0 |

| 200 | 15.0 | 785.0 | 15.0 |

| 200 | 20.0 | 780.0 | 20.0 |

| 200 | 25.0 | 775.0 | 25.0 |

| Table II.Preparation of 6-shogaol standard

solutions. |

Table II.

Preparation of 6-shogaol standard

solutions.

| Blank plasma,

µl | 6-shogaol, µl | Acetonitrile,

µl | Final

concentration, ng/ml |

|---|

| 200 | – | 800.0 | Blank |

| 200 |

2.5 | 797.5 |

2.5 |

| 200 |

5.0 | 795.0 |

5.0 |

| 200 | 10.0 | 790.0 | 10.0 |

| 200 | 15.0 | 785.0 | 15.0 |

| 200 | 20.0 | 780.0 | 20.0 |

| 200 | 25.0 | 775.0 | 25.0 |

Optimization of LC-MS analytical

conditions

The 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol standard solutions

(2.5, 5.0, 10.0, 15.0, 20.0 and 25.0 ng/ml) were filtered using

Millipore membranes (pore size 0.2 µm; EMD Millipore, Billerica,

MA, USA) and injected into the LC-MS RP-C18 column. The optimized

conditions of the LC-MS are presented in Table III.

| Table III.LC-MS optimum analytical conditions

for 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol (N2 gas temperature 350°C;

drying N2 gas flow rate 10 l/min; nebulizer pressure 50

psi). |

Table III.

LC-MS optimum analytical conditions

for 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol (N2 gas temperature 350°C;

drying N2 gas flow rate 10 l/min; nebulizer pressure 50

psi).

| LC-MS

parameter | Setting

condition |

|---|

| Merk/Type | Waters Xevo QTof

-MassLynx 4.1 SCN719 |

| Column | BEH Shield RP18 Ø

1.7 µm; 2.1 × 100 mm |

| Mobile phase | Phase A: 0.1% (v/v)

formic acid in water; phase B: acetonitrile |

| Time setting (ratio

phase A:phase B) | 0-6th min (38:62);

6–9th min (0:100); 9–15th min (38:62) |

| Flow rate;

retention time | 300 µl/min; 15

min |

| Mass spectrometer

mode/ion detection | Electrospray

ionization (ES+) ionization/multiple reaction monitoring mode |

Validation of analytical method

Selectivity

The selectivity of the method was investigated by

comparing the chromatogram of extracted blank plasma (3 ml)

obtained from six randomly selected participants described below,

each spiked with 25.0 ng/ml 6-shogaol.

Linearity

Linearity of the standard curves was calculated

using human plasma spiked with various concentrations (2.5, 5.0,

10.0, 15.0, 20.0 and 25.0 ng/ml) of 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol. The

concentrations were plotted against the area under curves (AUCs) of

the 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol chromatograms. The regression line

(y=ax+b) and the coefficient of correlation (r) of

the data were calculated.

Accuracy and precision

The accuracy and precision of the method were

evaluated by analyzing 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol in three sets of

quality control samples [lower concentration of quality control

(LCQC)=2.5 ng/ml; medium concentration of quality control (MCQC)=15

ng/ml; and higher concentration of quality control (HCQC)=25 ng/ml

each] within the same day. Each solution was injected into the

column in three replicates. The percentage recovery and standard

deviation (SD) were calculated to ascertain accuracy and precision

of the analytical method, respectively.

Limit of detection (LOD) and limit of

quantification (LOQ)

The LOD and LOQ were calculated by using:

LOD=(3×SD)/b; and LOQ=(10×SD)/b where b is the y-intercept

of the linear regression curve (25).

Subjects and treatment

A total of 21 participants (8 females and 13 males)

aged 21–30 years, with body mass indices (BMIs) of 18–25,

non-smokers and/or alcohol drinkers, were solicited by

advertisement from May to September 2017. All participants were

confirmed to be healthy by physical examination at Padjadjaran

Clinic, Padjadjaran University (Jatinangor, Indonesia; Table IV). Two of the participants (R14 and

R20) had low BP (90/60). Initially both were included in the study,

but one of them (R14) vomited during the treatment, and was

excluded. One of the participants (R21) was menstruating on the day

of preliminary health screening and was excluded. The remaining 19

subjects continued the study. All study procedures were

administered at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Padjadjaran University

following collection of signed written informed consent according

to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The subject

protocols and treatment were approved by the Research Ethics

Committee of Padjadjaran University (approval nos.

1211/UN6.C.10/PN/2017 for 10-gingerol and 924/UN6.C.10/PN/2017 for

6-shogaol). The subjects were asked to avoid all foods containing

ginger within 7 days prior to the project and completed a food

checklist to verify that they were not consuming any ginger-rich

food or beverages. All subjects received the Sundanese standard

meal (one portion of white rice equivalent to 240 cal, 100 g of

fried chicken/tofu equivalent to 110–120 cal, hot tea equivalent to

70 cal, and a banana/orange 3 times/day at 24 h pre-study and for

breakfast on the day of the study.

| Table IV.Preliminary health screening of the

participants. |

Table IV.

Preliminary health screening of the

participants.

|

|

| Health status |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Subject code | Age, years | Height, cm | Weight, kg | Blood type | BP, mmHg | Result |

|---|

| R1 | 22 | 160 | 63 | A | 120/80 | Healthy |

| R2 | 21 | 164 | 61 | O | 120/80 | Healthy |

| R3 | 21 | 176 | 72 | AB | 110/70 | Healthy |

| R4 | 22 | 164 | 64 | B | 110/70 | Healthy |

| R5 | 22 | 175 | 63 | O | 120/80 | Healthy |

| R6 | 22 | 165 | 55 | A | 110/80 | Healthy |

| R7 | 22 | 172 | 56 | A | 110/70 | Healthy |

| R8 | 22 | 165.5 | 66 | O | 120/80 | Healthy |

| R9 | 22 | 164 | 55 | O | 100/60 | Healthy |

| R10 | 25 | 169 | 60 | B | 120/80 | Healthy |

| R11 | 26 | 168 | 65 | O | 120/80 | Healthy |

| R12 | 30 | 161 | 58 | A | 100/70 | Healthy |

| R13 | 22 | 164 | 54 | A | 100/70 | Healthy |

| R14 | 23 | 157 | 65 | O | 90/60 |

Excludeda |

| R15 | 22 |

160.5 | 49 | AB | 100/70 | Healthy |

| R16 | 22 | 155 | 48 | AB | 120/80 | Healthy |

| R17 | 25 | 157 | 48 | O | 100/70 | Healthy |

| R18 | 25 | 145 | 45 | O | 100/80 | Healthy |

| R19 | 23 | 159 | 51 | O | 100/70 | Healthy |

| R20 | 22 | 155 | 44 | A | 90/60 | Healthy |

| R21 | 23 | 157 | 62 | B | 110/80 |

Excludedb |

The red ginger suspension was administered the

subsequent morning after the standard breakfast had been received.

Each subject was given one portion of red ginger suspension (2 g in

15 ml of water) as a single oral dose, and 3 ml blood samples were

taken from the subjects at baseline (0 min), 30, 60, 90, 120 and

180 min. The blood was put into the K2EDTA vacutainer tubes. Plasma

was separated by centrifuging at 20,440 × g for 15 min at room

temperature and kept at −20°C until assayed.

Pharmacokinetics of 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol

Analysis of 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol was performed

by dissolving 200 µl of the subjects' plasma in 800 µl

acetonitrile. The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged at 20,440 ×

g for 15 min at room temperature. The supernatant was filtered

using Millipore membrane (pore size 0.2 µm) and injected into the

RP-C18 column embedded in the LC-MS XEVO-QTOFMS.

Results and Discussion

Identification of 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol in Z. officinale var. Rubrum suspension

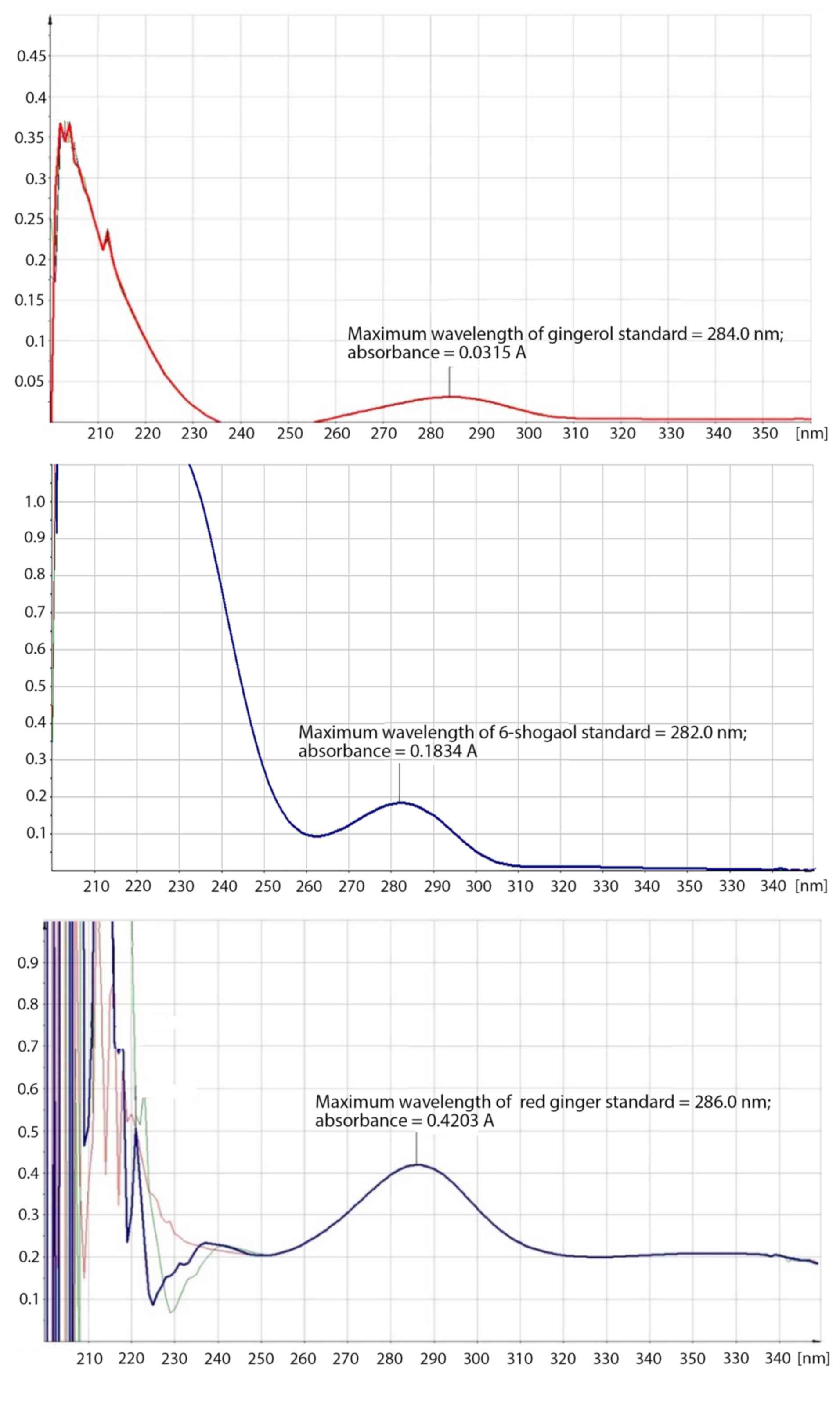

Gingerol and/or shogaol were indicated to be present

in the red ginger suspension by the λmax of red ginger suspension

in methanol (λmax=286 nm) which was similar to those of 10-gingerol

(λmax=284 nm) and 6-shogaol (λmax=282 nm; Fig. 2).

Ethanol can extract gingerols more effectively than

water; moreover, hot water is reportedly more effective than cold

water (26). Ghasemzadeh et al

(27) when working on the

optimization procedure for the extraction of 6-gingerol and

6-shogaol (focusing on temperature 50–80°C and time 2–4 h) reported

that increasing the extraction temperature (up to 76.9°C) and time

(3. h) induced the highest yield of 6-gingerol (2.74 mg/g dry

weight) and 6-shogaol (1.59 mg/g dry weight) from Z.

officinale var. Rubrum Theilade (27). The present work employed hot distilled

water (70°C) to extract 2 g of the red ginger (Z. officinale

var. Rubrum) powder.

Validation of analytical method

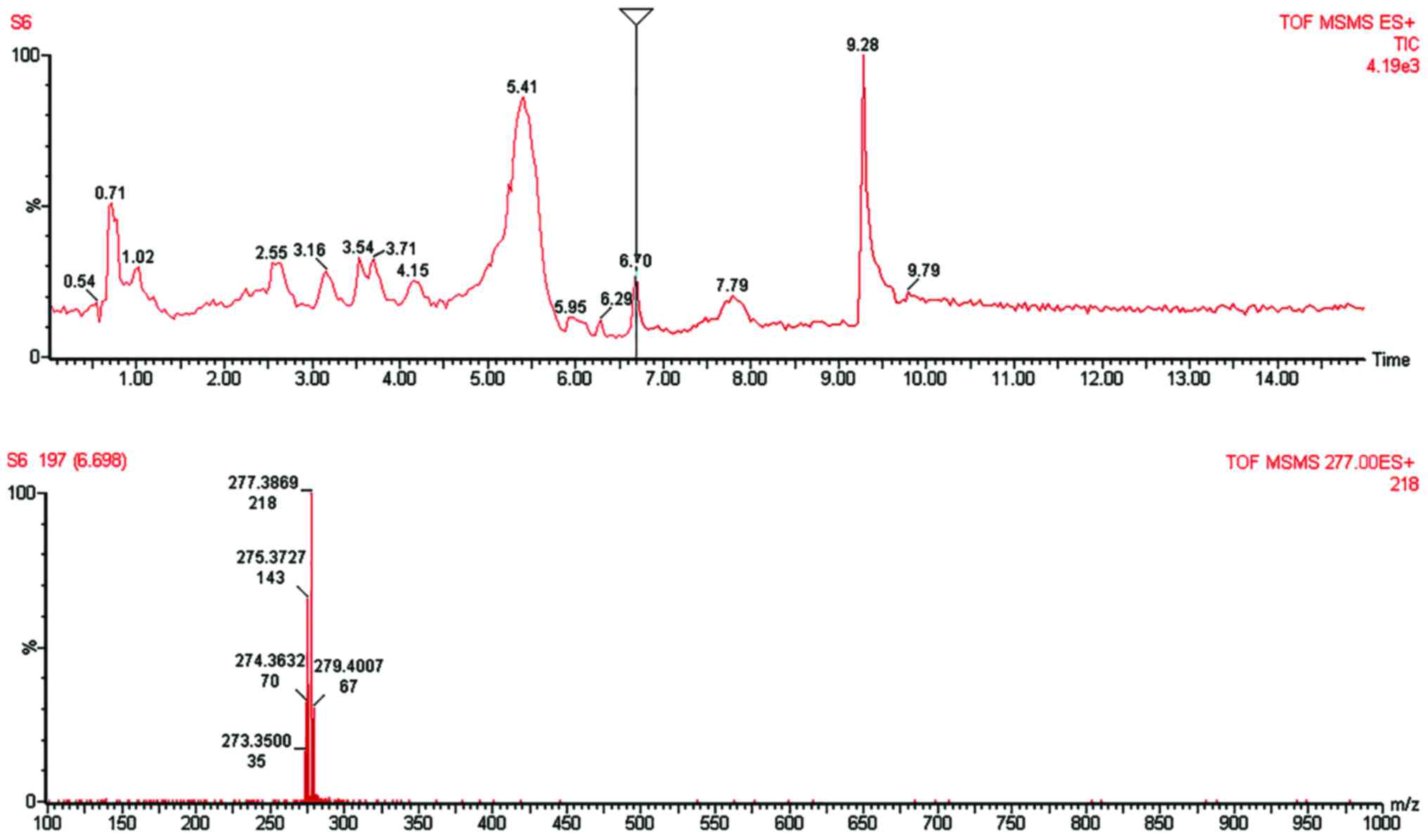

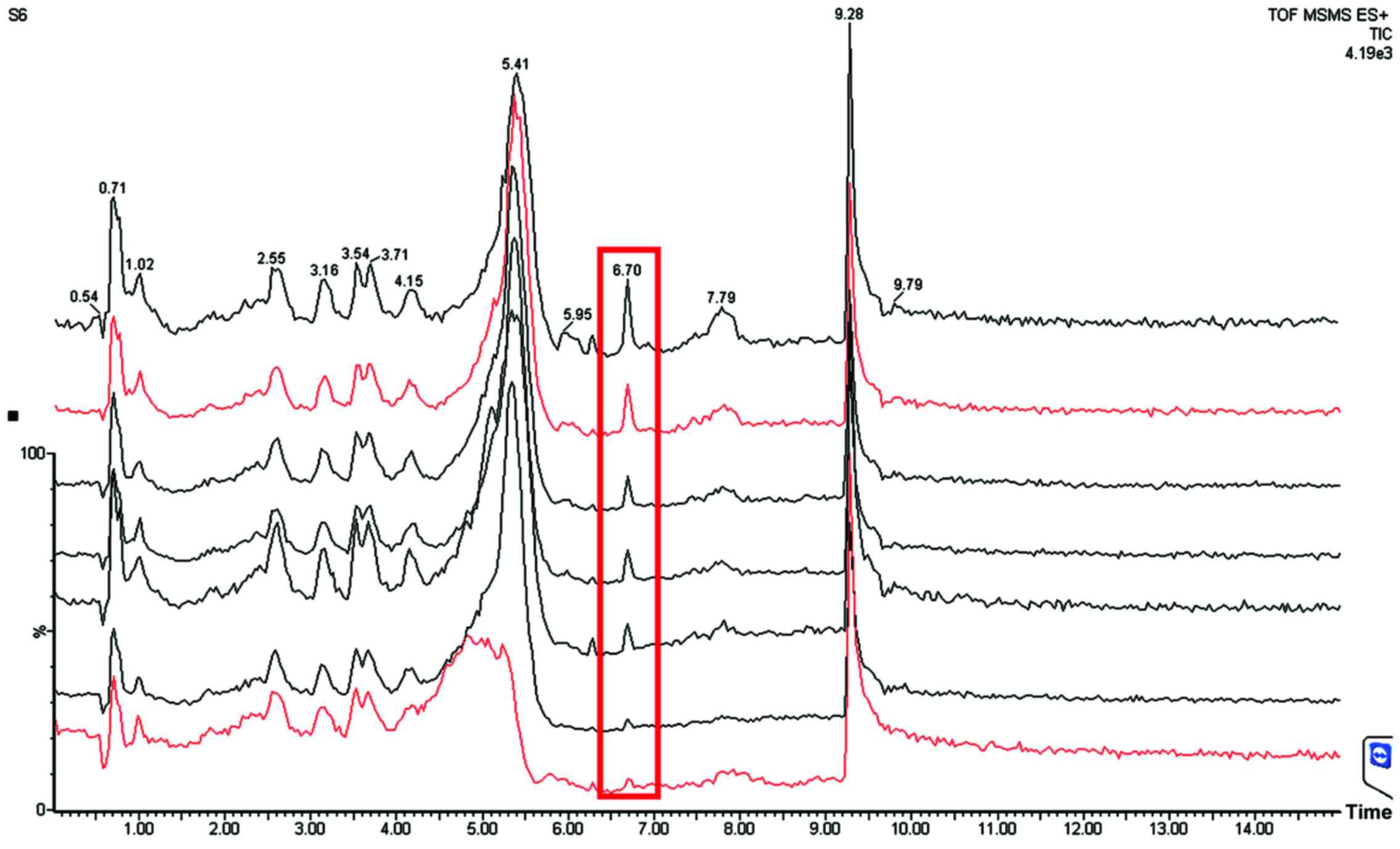

The LC-MS analytical method was selective for both

6-shogaol (Fig. 3) and 10-gingerol

(Fig. 4) as proven by the respective

chromatogram peaks that were free of interference at the retention

time of 6-shogaol (6.70 min) and 10-gingerol (8.26 min). The MS

spectrum confirmed and correlated the chromatogram peak with the

mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). Our MS spectra indicated the base peak

of 6-shogaol [M+1] (m/z=277.3869; MW 6-shogaol=276.376); and the

base peak of 10-gingerol [M+1] (m/z=351.2959; MW

10-gingerol=350.4923).

Linearity of the standard curves was constructed

using human plasma spiked with various concentrations (2.5, 5.0,

10.0, 15.0, 20.0 and 25.0 ng/ml) of 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol

(Fig. 5). The LCQC (2.5 ng/ml), MCQC

(15.0 ng/ml) and HCQC (25.0 ng/ml) of the ginger analytes were

assayed on an intra-day basis to determine the accuracy and

precision of the method. The intra-day values for the SD ranged

from 0.16–0.69 for 10-gingerol and 0.74–1.49 for 6-shogaol, whereas

the recovery of the analytes was 100.64–104.44% for 10-gingerol and

103.40–104.22% for 6-shogaol. The data (plot of AUC of the

chromatogram peak against the concentration of

10-gingerol/6-shogaol; not shown) correlated as indicated by r

values >0.99 (Table V).

| Table V.Validation of the 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol analytical method. |

Table V.

Validation of the 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol analytical method.

| Concentration of

analyte, ng/ml | Mean concentration,

ng/ml | Standard

deviation | Recovery, % | Coefficient of

correlation (r) | Slope |

|---|

| 10-gingerol |

|

2.5 |

2.53 | 0.16 | 101.28 |

|

|

|

15.0 | 15.67 | 0.57 | 104.44 | 0.9991 | 6.3195 |

|

25.0 | 26.16 | 0.69 | 100.64 |

|

|

| 6-shogaol |

|

2.5 |

2.59 | 0.74 | 103.40 |

|

|

|

15.0 | 15.63 | 1.49 | 104.22 | 0.9987 | 2.7070 |

|

25.0 | 26.04 | 0.78 | 104.14 |

|

|

The LODs in human plasma for 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol were 1.31 and 1.51 ng/ml, respectively, and the LOQs were

4.36 and 5.03 ng/ml, respectively.

Characteristics of the subjects

All 19 subjects who completed the study were proven

healthy by a physical examination upon enrollment (Table IV); however, 3–6 months prior to the

start of the study, several subjects had suffered from gastritis

(1/19; 5.26%), allergy (7/19; 3.68%; cold urticaria and/or seafood

allergy), joint arthritis (1/19; 5.26%) and dengue hemorrhagic

fever (1/19; 5.26%). The subjects also confirmed their weekly

exercise as jogging and walking (7/19; 3.68%), football (2/19;

10.53%) and badminton (1/19; 5.26%).

Pharmacokinetics of 10-gingerol and

6-shogaol

10-gingerol and 6-shogaol could be quantified in the

plasma of healthy subjects treated with a single dose of red ginger

suspension. They were eluted at 6.80 min (6-shogaol) and 8.0 min

(10-gingerol; Fig. 6), compared with

the pure compounds (for 6-shogaol, 6.70 min and for 10-gingerol,

8.26 min; Figs. 3 and 4), respectively. There was a slight

difference of elution time between the standards (pure 6-shogaol

and 10-gingerol compounds) and that of red ginger suspension due to

different conditions; the standards were spiked in vitro

into human plasma, while the red ginger suspension was administered

orally and taken ex vivo from the subjects' blood. The

pharmacokinetic profile of each of the red ginger compounds is

presented in Table VI.

| Table VI.Pharmacokinetic profile of

10-gingerol and 6-shogaol in the plasma of healthy subjects treated

with a single dose of red ginger suspension. |

Table VI.

Pharmacokinetic profile of

10-gingerol and 6-shogaol in the plasma of healthy subjects treated

with a single dose of red ginger suspension.

| Parameter

(n=19) | 10-gingerol | 6-shogaol |

|---|

| AUC, ng/ml/min |

948.750 |

268.140 |

| Cmax, ng/ml |

160.49 |

453.40 |

| Tmax, min | 38 | 30 |

| T½ elimination,

min | 336 | 149 |

According to elimination half-lives (T½),

10-gingerol and 6-shogaol were eliminated from the plasma at 336

and 149 min, respectively (Table

VI). The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of 10-gingerol

(160.49 ng/ml) was lower than that of 6-shogaol (453.40 ng/ml;

Table VI).

These findings were different to those of Zick et

al (22) who studied the

pharmacokinetic profile of 6-, 8- and 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol in

dry extract of ginger at doses of 100 mg to 2 g in 27 healthy

American participants (9 males, 22 females, mostly Caucasians).

They identified that no free 6-, 8-, 10-gingerol or 6-shogaol was

present, but 6-, 8- and 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol glucuronides were

detected. Furthermore, in the plasma of healthy Caucasians, the

concentration of 10-gingerol has been quantified higher than that

of 6-shogaol (23).

The present study used a single dose (2 g) of red

ginger (Z. officinale var. Rubrum) suspension, administered

orally to 19 healthy Indonesian participants (13 males and 6

females). Both 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol could be detected and

quantified. In the plasma of the healthy Indonesians, 10-gingerol

was quantified to a lower level than 6-shogaol.

10-gingerol and 6-shogaol exhibited slower

elimination in Indonesian subjects compared with that in Caucasians

(T½ elimination <120 min). In the current study, no serious

adverse effects were reported following ingestion of the red ginger

suspension, though several female subjects complained of the potent

pungent odor and spicy taste that caused stomach discomfort. These

mild adverse effects were consistent with those reported by Zick

et al (22) and in a previous

review study by Chrubasik et al (28), who documented that the majority of the

disadvantages were transient gastrointestinal reactions, such as

gas and bloating.

In conclusion, 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol were

absorbed after per oral single dose of red ginger suspension and

could be quantified in the plasma of healthy Indonesian subjects.

The Cmax of 10-gingerol (160.49 ng/ml) was lower than that of

6-shogaol (453.40 ng/ml). Notably, the two red ginger analytes

exhibited relatively slow elimination half-lives. In the present

trial, no serious adverse effects were reported following ingestion

of the red ginger suspension, but several female subjects

complained about the potent pungent odor and spicy taste that

caused stomach discomfort. Overall, the present pharmacokinetic

findings of 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol in Indonesian subjects

confirmed that different ethnicities may contribute to different

pharmacokinetic profiles. Identification of these differences may

lead to personalized-medicine, and thus contribute in a clinical

context, particularly in the discovery and development of

anti-inflammatory drugs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Tri

Hanggono Achmad, Rector of Universitas Padjadjaran (West Java,

Indonesia) for facilitating and supporting this research project.

The present work was conducted in the framework of the master

theses of DMS and RDS at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Padjadjaran

University, Jatinangor, West Java, Indonesia. The authors are also

thankful to Dr. Joko Kusmoro at the Laboratory of Plant Taxonomy,

Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences,

Padjadjaran University, for identifying the plant specimen.

Funding

The present study was funded by the

Academic-Leadership Grant Universitas Padjadjaran Batch-II 2017,

research contract no. 872/UN6.3.1/LT/2017.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current

work are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

JL and AD were principally responsible for

conception and design of the study. JL, MM and AD participated in

the acquisition of the reported data. DMS, RDS, SM and MF

participated in the processing, analysis and interpretation of the

reported data. JL and SM contributed to the writing and revising of

the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

to be published.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants. Research Ethics Committee of Padjadjaran University

(Bandung, Indonesia) approved the study procedures (approval nos.

1211/UN6.C.10/PN/2017 for 10-gingerol and 924/UN6.C.10/PN/2017 for

6-shogaol).

Patient consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained for publication of the

participants' data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhang X, Iwaoka WT, Huang AS, Nakamoto ST

and Wong R: Gingerol decreases after processing and storage of

ginger. J Food Sci. 59:1338–1340. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hiserodt RD, Franzblau SG and Rosen RT:

Isolation of 6-, 8-, and 10-gingerol from ginger rhizome by HPLC

and preliminary evaluation of inhibition of Mycobacterium

avium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Agric Food Chem.

46:2504–2508. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Young HY, Chiang CT, Huang YL, Pan FP and

Chen GL: Analytical and stability studies of ginger preparations.

Yao Wu Shi Pin Fen Xi. 10:149–153. 2002.

|

|

4

|

Riaz H, Begum A, Raza SA, Khan ZMUD,

Yousaf H and Tariq A: Antimicrobial property and phytochemical

study of ginger found in local area of Punjab, Pakistan. Int Curr

Pharm J. 4:405–409. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Ugwoke CEC and Nzekwe U: Phytochemistry

and proximate composition of ginger (Zingiber officinale). J

Pharm Allied Sci. 7:No. 5. 2010.

|

|

6

|

Bhargava S, Dhabhai K, Amla Batra A,

Sharma A and Malhotra B: Zingiber officinaleChemical and

phytochemical screening and evaluation of its antimicrobial

activities. J Chem Pharm Res. 4:360–364. 2012.

|

|

7

|

Prasad S and Tyagi AK: Ginger and its

constituents: Role in prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal

cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015:1429792015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Marrelli M, Menichini F and Conforti F: A

comparative study of Zingiber officinale Roscoe pulp and

peel: Phytochemical composition and evaluation of antitumour

activity. Nat Prod Res. 29:2045–2049. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mashhadi NS, Ghiasvand R, Askari G, Hariri

M, Darvishi L and Mofid MR: Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory

effects of ginger in health and physical activity: Review of

current evidence. Int J Prev Med. 4 Suppl 1:S36–S42.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Dhanik J, Arya N and Nand V: A review on

Zingiber officinale. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 6:174–184.

2017.

|

|

11

|

Jiang H, Sólyom AM, Timmermann BN and Gang

DR: Characterization of gingerol-related compounds in ginger

rhizome (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) by high-performance

liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry.

Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 19:2957–2964. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tjendraputra E, Tran VH, Liu-Brennan D,

Roufogalis BD and Duke CC: Effect of ginger constituents and

synthetic analogues on cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme in intact cells.

Bioorg Chem. 29:156–163. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Afzal M, Al-Hadidi D, Menon M, Pesek J and

Dhami MSI: Ginger: An ethnomedical, chemical and pharmacological

review. Drug Metab Drug Interact. 18:159–190. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Grzanna R, Phan P, Polotsky A, Lindmark L

and Frondoza CG: Ginger extract inhibits beta-amyloid

peptide-induced cytokine and chemokine expression in cultured THP-1

monocytes. J Altern Complement Med. 10:1009–1013. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lantz RC, Chen GJ, Sarihan M, Sólyom AM,

Jolad SD and Timmermann BN: The effect of extracts from ginger

rhizome on inflammatory mediator production. Phytomedicine.

14:123–128. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ghasemzadeh A, Jaafar HZ and Rahmat A:

Variation of the phytochemical constituents and antioxidant

activities of Zingiber officinale var. Rubrum Theilade

associated with different drying methods and polyphenol oxidase

activity. Molecules. 21:7802016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Dugasani S, Pichika MR, Nadarajah VD,

Balijepalli MK, Tandra S and Korlakunta JN: Comparative antioxidant

and anti-inflammatory effects of [6]-gingerol, [8]-gingerol,

[10]-gingerol and [6]-shogaol. J Ethnopharmacol. 127:515–520. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ippoushi K, Azuma K, Ito H, Horie H and

Higashio H: [6]-Gingerol inhibits nitric oxide synthesis in

activated J774.1 mouse macrophages and prevents

peroxynitrite-induced oxidation and nitration reactions. Life Sci.

73:3427–3437. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kim SO, Kundu JK, Shin YK, Park JH, Cho

MH, Kim TY and Surh YJ: [6]-Gingerol inhibits COX-2 expression by

blocking the activation of p38 MAP kinase and NF-kappaB in phorbol

ester-stimulated mouse skin. Oncogene. 24:2558–2567. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fikri F, Saptarini NM, Levita J, Nawawi A,

Mutalib A and Ibrahim S: The inhibitory activity on the rate of

prostaglandin production by Zingiber officinale var. Rubrum.

Pharmacol Clin Pharm Res. 1:33–40. 2016.

|

|

21

|

Saptarini NM, Sitorus EY and Levita J:

Structure-based in silico study of 6-gingerol, 6-ghogaol, and

6-paradol, active compounds of ginger (Zingiber officinale)

as COX-2 inhibitors. Int J Chem. 5:12–18. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zick SM, Djuric Z, Ruffin MT, Litzinger

AJ, Normolle DP, Alrawi S, Feng MR and Brenner DE: Pharmacokinetics

of 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, 10-gingerol, and 6-shogaol and conjugate

metabolites in healthy human subjects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers

Prev. 17:1930–1936. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yu Y, Zick S, Li X, Zou P, Wright B and

Sun D: Examination of the pharmacokinetics of active ingredients of

ginger in humans. AAPS J. 13:417–426. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zick SM, Ruffin MT, Djuric Z, Normolle D

and Brenner DE: Quantitation of 6-, 8-, and 10-gingerols and

6-shogaol in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography

with electrochemical detection. Int J Biomed Sci. 6:233–240.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Şengül Ü: Comparing determination methods

of detection and quantification limits for aflatoxin analysis in

hazelnut. Yao Wu Shi Pin Fen Xi. 24:56–62. 2016.

|

|

26

|

Wohlmuth H: Phytochemistry and

pharmacology of plants from the ginger family, Zingiberaceae

(unpublished PhD thesis). Southern Cross University; Lismore, New

South Wales: 2008

|

|

27

|

Ghasemzadeh A, Jaafar HZ and Rahmat A:

Optimization protocol for the extraction of 6-gingerol and

6-shogaol from Zingiber officinalevar. rubrum

Theilade and improving antioxidant and anticancer activity using

response surface methodology. BMC Complement Altern Med.

15:2582015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chrubasik S, Pittler MH and Roufogalis BD:

Zingiberis rhizoma: A comprehensive review on the ginger effect and

efficacy profiles. Phytomedicine. 12:684–701. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|