Introduction

The brain is one of the body's most important

organs, and as such has both a specific role and occupies a primary

position in the organism (1). The

brain is of high energy consumption (2,3) and

low energy capacity (4,5). In addition, the brain also exhibits

substrate specificity with the preference of lactate, ketones and

glucose (6,7). All of the above features contribute

to the mechanisms underlying energy absorption and utilization.

Numerous studies investigated the mechanism underlying the brain's

ability for selfishness, the combined results of which formed the

'selfish brain' theory (8–12). As previous results have

demonstrated, in order to satisfy its energy requirements, the

brain prioritizes the adjustment of its own ATP concentration when

regulating the allocation of energy from food sources (9). The brain activates its stress system

to compete for energy resources with other organs (allocation), and

alters appetite (food intake) in order to alleviate the stress

system and return to a state of rest (10). Under conditions of stress or

nutrient deficiency, the brain safeguards its own energy supply

even if this requires sacrificing the energy requirements of other

organs.

Two basic hypotheses have been proposed to explain

how the brain uses its regulatory methods to compete with other

organs under harsh conditions: The 'lipostatic' theory and the

'glucostatic' theory. The former was originally proposed by Kennedy

(11), and proposed that the brain

relied on the leptin hormones in fat and muscle tissue as feedback

signals (12–14). The latter proposed that blood

glucose levels were used as an indicator, an important factor in

the central regulatory system (15), and the brain's so called

'selfishness' would therefore be based on cerebral insulin

suppression (10,16). However, the adequate supply of

energy to the brain is the result of both lipid conversion and the

continuous supply of glucose, which combine elements of both the

glucose and the lipostatic theory. Previous studies on the brain

revealed that the mechanism underlying the physiological regulation

and feedback signaling pathways of energy predominantly focus on

absorbing energy from peripheral neurons and other organs (8,9).

Whether the brain uses its own substances as part of its energy

supply source, and the role of water content in the maintenance of

brain mass remain to be fully elucidated. Alterations in water

content and the mechanisms underlying its regulation may further

clarify the 'selfish brain' theory. The present study aimed to

investigate the self-regulation of the brain under food and/or

water shortage by examining autophagy and water control by AQPs.

AQPs have a well-established role in water balance (17), and 6 of the 13 AQP family members

have been identified in the brain. AQP-1 and 4 were observed to be

the most representative proteins in the regulation of brain water

content, and were demonstrated to be associated with cerebral edema

(18–20). In addition, energy regulation and

autophagy were also important for the brain to acquire sufficient

energy. In the present study, LC3 was introduced as a protein

marker to evaluate brain autophagy (21). LC3I can be phosphorylated to LC3II

during autophagy. Therefore, brain autophagy is reflected by

LC3II/LC3I (22). The results of

the present study may further the understanding of the 'selfish

brain' theory. In addition, it may provide strategies against

nutrient deficiency in humans and animals, predominantly based on

the target genes of AQPs and autophagy.

Materials and methods

Animal grouping and tissue sample

preparation

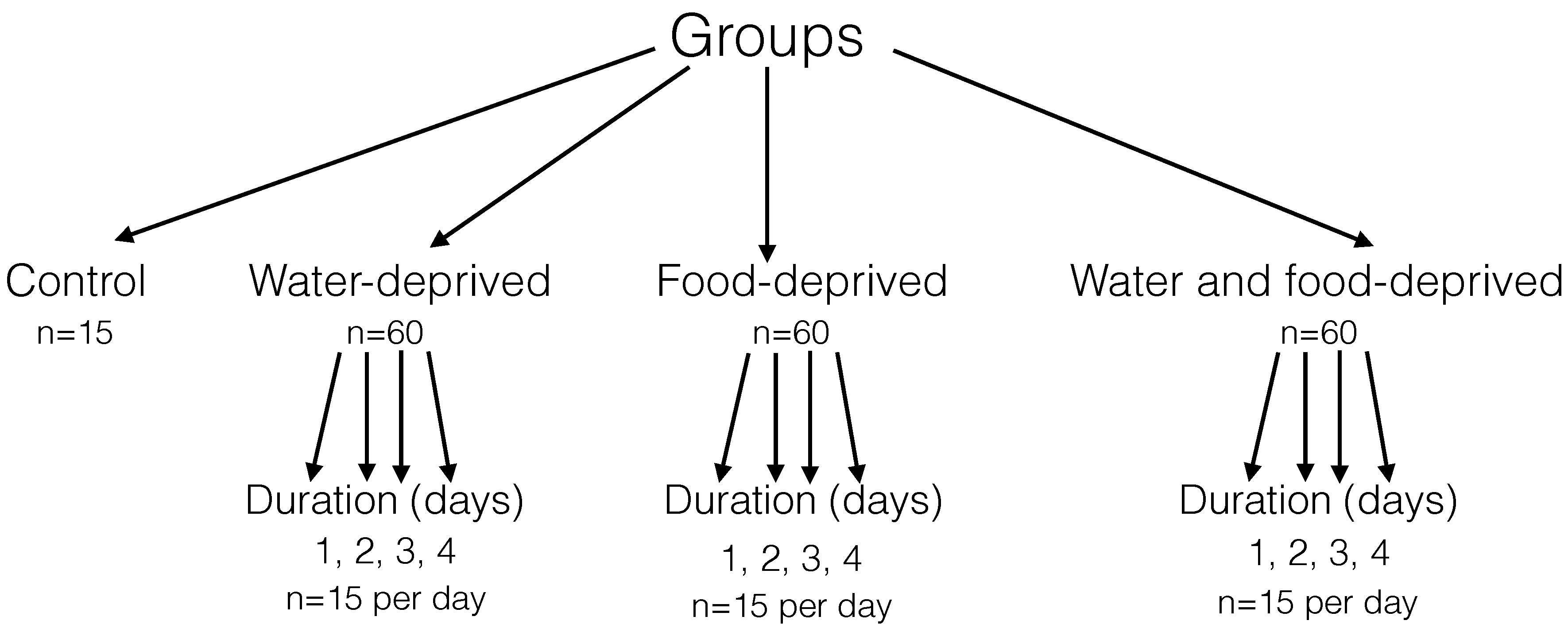

A total of 195 female Balb/c mice (18–20 g, 4-weeks

old) were provided by Vital River Laboratories Co., Ltd. (Beijing,

China). All the mice were raised in the Experimental Animal Center

of Beijing Institute of Radiation Medicine (Beijing, China) and

maintained in specific pathogen free grade animal facility. All

experiments were performed between 08:00 and 15:00 h. A maximum of

five mice were housed in one cage during an experiment. The feeding

room was maintained at a constant temperature of 25°C with normal

ventilation and a natural light/dark cycle. The mice were randomly

divided into four primary groups: A control group (n=15), a

water-deprived group (n=60), a food-deprived group (n=60) and a

water and food-deprived group (n=60). Then animals in each

experimental primary group (except the control group) were the

further divided into four secondary groups (n=15) with deprivation

durations of 1, 2, 3, 4 days. Among the mice of each secondary

group, five were used for histological observation, five for the

water content assay, and the remaining five mice were used for RNA

and protein detection (Fig. 1).

However, prior to dissection, all mice were sacrificed by cervical

dislocation. Mice in each secondary group were dissected and the

brain was harvested. The brain tissue samples (5 brains from each

subgroup) were washed with normal saline and then fixed in formalin

(Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd, Beijing, China) prior to

hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The remaining 10 brains

were frozen at −80°C for RNA and protein extraction.

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance

with guidance for the use of experimental animals following

approval by the Committee of Animal Care and Use Committee of

Beijing Institute of Radiation Medicine (Beijing, China).

Body weight and blood glucose

detection

Mice were weighed everyday during the experiment.

The data were collected to construct a growth curve. In addition,

blood glucose concentrations were detected each day as basic

physiological indexes among the three experimental groups. Blood

glucose was measured using blood glucose test strips (Roche

Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's

protocol.

Analysis of water content

Lyophilization was used to detect the water content

of the brain tissue samples. The tissue samples of the five mice

from all secondary groups were pre-frozen in a −80°C freezer for 12

h, lyophilized in a −50°C vacuum freeze-drying instrument (model

FD-1A-50; Beijing Boyikang Laboratory Instruments Co., Ltd.,

Beijing, China) for 24 h, and then weighed to calculate the water

content.

H&E staining

Tissue samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde

solution (pH 7.0; Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.) for two

days, and then processed for paraffin sectioning using a paraffin

slicer (RM2235, Leica Microsystems, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

The sections (5 µm) were stained with hematoxylin (Sinopharm

Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd.) for 3 min, washed in tap water for 30

min, and de-stained in warm water for 10 sec. The sections were

then washed again in running water for 15 min, and stained with

eosin (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.) for 15 sec prior to

washing for 20 min. The brain tissue sections were finally

dehydrated using alcohol gradients, prior to xylene (Sinopharm

Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd.) clearance and cover slipping. The

stained sections were observed under a light microscope (DM2500,

Leica Microsystems, Inc.).

RNA and protein extraction

The −80°C preserved brain samples (100 mg/sample)

were homogenized using a handheld grinder (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 min on ice. Total RNA

from the mouse brains was extracted using Total RNA kits II (Omega

Bio-Tek, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Then, the extracted RNA (1 µg) was reverse

transcribed into cDNA using a Reverse Transcription system

(Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Total protein of the animal tissue samples preserved

at -80°C was extracted using a cell lysis buffer (Applygen

Technologies, Inc., Beijing, China) containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4),

150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1

mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM

protease inhibitor, prior to western blotting.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

(qPCR) analysis of AQP in the brain

qPCR was performed using an Illustra Ready-to-Go

RT-qPCR kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Chalfont, UK). All

reactions were performed in a MasterCycler machine (Eppendorf,

Hauppauge, NY, USA) under an initial denaturing step at 94°C for 5

min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C denaturation for 30 sec, 55°C

annealing for 30 sec, and 72°C extension for 1 min. The genes of

the AQP family were amplified by PCR using the following primers

with β-actin as a reference gene: β-actin forward,

5′-ATGATGCCCCCAGGGCTGTGTT-3′ and reverse,

5′-TTGCTCTGGGCCTCATCACCCA-3′; Aqp1 forward,

5′-TTCTGGGTGGGGCCGTTCATTG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TCTGTGAAGTCGCTGCTGCGTG-3′; and Aqp4 forward,

5′-AGGAAGCCTTCAGCAAAGCCGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-ACTTGGCTCCGGTTGTCCTCCA-3′. The primers were designed by the

multiplex PCR primer designing web server (https://sourceforge.net/projects/mpprimer/) (23). PCR products were identified by 2%

agarose gel electrophoresis (Sigma-Aldrich), and expression levels

were quantified by image analysis using Image J for integrated

optical density analysis (version 2x; National Institutes of

Health, Bethesda, MA, USA), and then plotted using Origin 8.1

software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). All

experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Western blot analysis of brain autophagy

marker protein LC3I/II

Total proteins (30 pg) extracted from the tissue

samples from the various groups were separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE at

60 V for 2.5 h. The proteins were then transferred to a

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PVDF; GE Healthcare Life

Sciences) following the manufacturer's protocol. Then, the PVDF

membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1

h. The membrane was probed with mouse-derived anti-LC3 primary

antibody [1:2,000 in 0.1% phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20

(PBST; Sigma-Aldrich), and mouse-derived anti-β-actin primary

antibody (1:3,000 in PBST; Sigma-Adrich)] overnight at 4°C. The

membranes were washed for 10 min, 3 times with PBST resolution

prior to incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat

anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:5,000 in PBST, Beijing Zhongshan

Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 1 h at

room temperature. Chemiluminescence substrate luminal reagent (GE

Healthcare Bio-Sciences) was used to detect the immunolabeled bands

by exposure to X-ray films (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA). Protein

bands were also analyzed using the above-mentioned ImageJ software.

All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard error.

One-repeated measure analysis of two factors factorial design was

using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institure, Cary, NC, USA). One-way

analysis of variance was performed in order to test for significant

differences between the groups. Multiple comparisons were performed

using the Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Brain mass was maintained with reducing

body weight and blood glucose levels

Body weight (g) and blood glucose levels (mmol/l)

were measured throughout the duration of the experiment. The body

weight of the mice reduced in the water and/or food deprivation

groups in a time-dependent manner, and specifically in the group

subjected to both food and water deprivation (Fig. 2A). The levels of blood glucose were

markedly reduced on the first day of deprivation. In both the food

deprivation group or the food and water deprivation group, the

levels of blood glucose were rapidly reduced from the second to the

fourth day. As expected, food was important for the maintenance of

blood glucose levels. Mice in the water deprivation group also

presented a decline in the blood glucose levels, although this

reduction was not as marked as the other two groups (Fig. 2B). Conversely to body weight, the

brain weight of the mice in the three primary experimental groups

remained relatively stable (Fig.

2C). Therefore, the ratios of brain weight to whole body weight

(%) increased with body weight loss (Fig. 2D).

Brains of the mice are the last organ to

suffer cell injury

The brains of the mice were the last organ to suffer

cell injury. To examine the cell morphology of the murine tissue

samples under experimental conditions, the paraffin tissue sections

were stained with H&E. As the duration of water or food

shortage increased, no significant injuries in the brain structure

were observed among the four groups (Fig. 3). Compared with other organs, the

brain was the last organ to suffer cell injury in the body, as

determined by histological observation (Fig. 3)

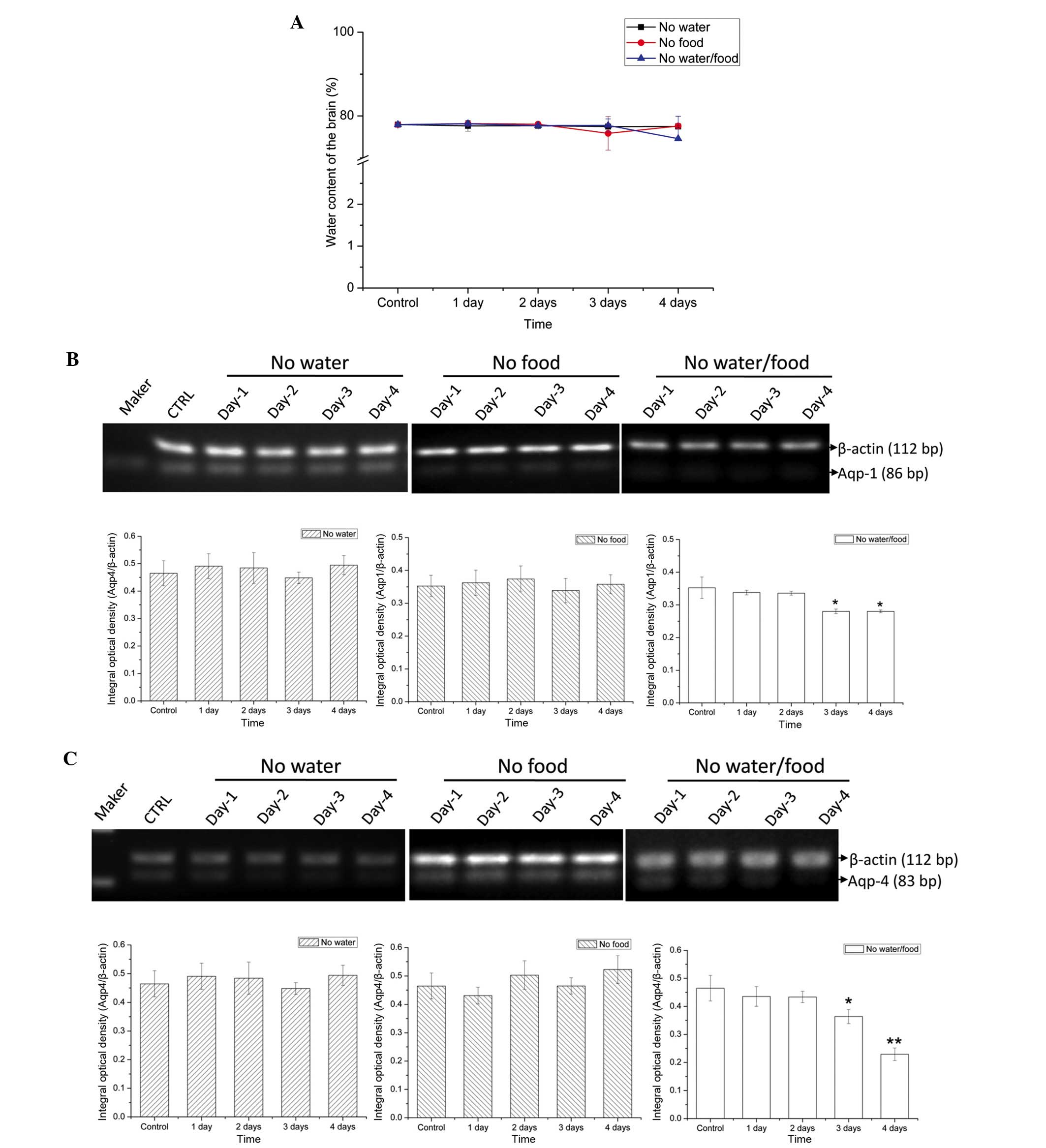

AQPs regulated the water content

To further explore the ability of the brain to

maintain its own function under severe conditions, brain tissue

samples were examined for water content at each experimental time

point. Compared with the other organs, the water content of the

brain (%) showed no significant reduction (Fig. 4A), suggesting that the brain may

have the ability to sequester water under harsh conditions.

Furthermore, to investigate the mechanism underlying water

regulation, the expression levels of two important proteins of the

AQP family, AQP 1 and 4, were examined. Compared with the control

group, there were no significant alterations in AQP 1 and 4

expression levels in the water-deprived and food-deprived groups

(Fig. 4B and C). However, in the

water and food deprivation group, the expression levels of both AQP

1 and 4 decreased significantly on the third day of deprivation

(AQP1, P=0.03671; AQP4, P=0.02854) and the fourth day (AQP1,

P=0.03637; AQP4, P=0.00231; Fig. 4B

and C), suggesting that the brain may have a regulatory role in

maintaining water balance through AQPs.

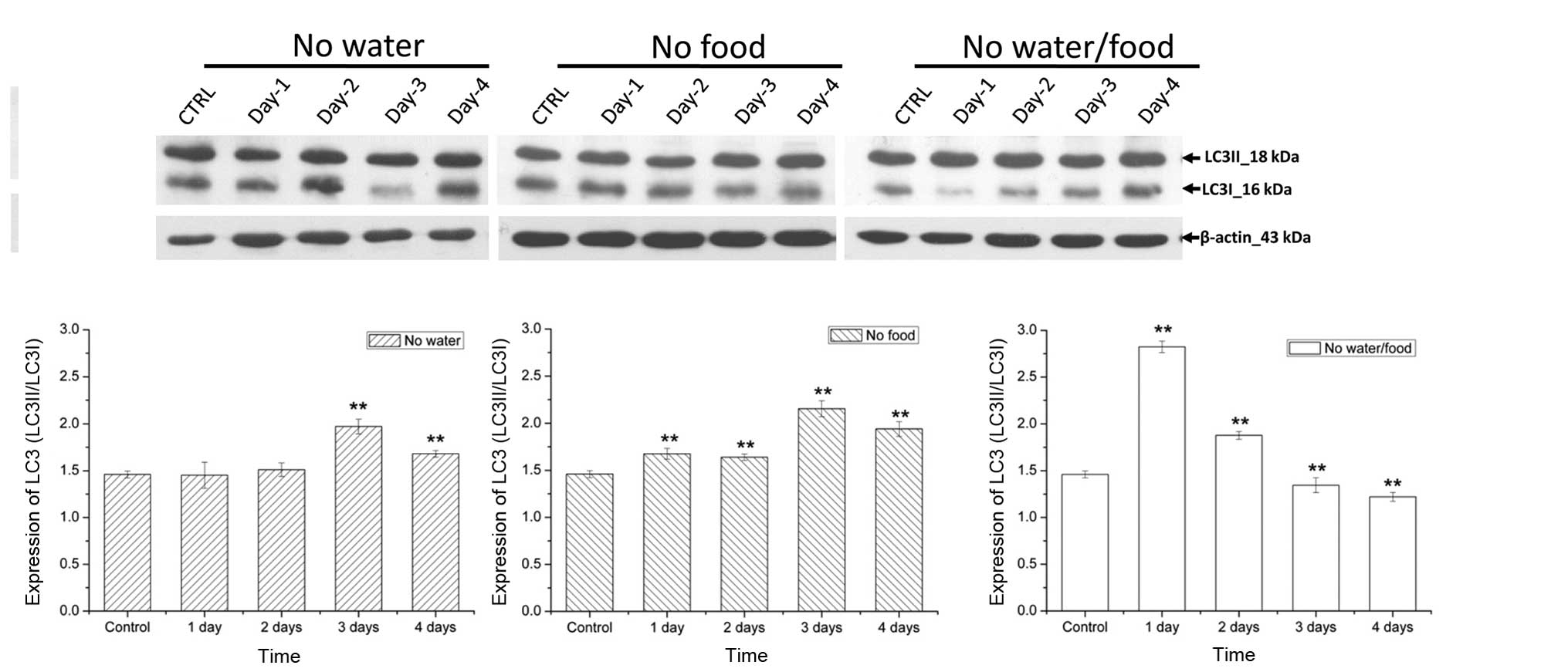

Autophagy is involved in brain survival

during lack of water and food

Energy supply was also investigated to further

elucidate the mechanism underlying the ability of the brain to

function under harsh conditions of deprivation. LC3II/I served as

marker proteins examine the activity levels of autophagy in brain.

The expression levels of LC3II/LC3I (%) in the food deprivation

group increased significantly compared with those in the control

group on the first day of deprivation (P=0.00812), indicating that

autophagy was maintained at a high level during food deprivation

(Fig. 5). However, in the water

deprivation group, the expression levels of LC3II/LC3I increased

significantly from the third day (P= 0.00592). In addition, the

LC3II/LC3I expression levels increased significantly from the first

day in the food and water deprivation group, indicating that the

activity levels of autophagy appeared early and increased under

simultaneous deprivation conditions (Fig. 5).

Discussion

In the present study, mice were deprived of water

and/or food. Under each experimental condition of nutritional

deficiency, the body weight was reduced whereas brain weight was

maintained whether under water or food shortage. These results were

consistent with the 'selfish brain' theory (10,24).

In addition, food shortage markedly reduced blood glucose

concentrations, however, water deprivation did not cause such

effects. Furthermore, both water and food deprivation caused energy

deficiency, which may activate the energy regulation system. Under

severe energy shortage, the brain may be able to protect itself by

becoming the last unaffected organ with steady water content and

normal physiological structures. Therefore, it is important to

elucidate the mechanism underlying the brain's unique selfish

ability under harsh conditions. Considering the important role of

the brain, the present study focused on water regulatory proteins

and autophagy-associated proteins in the brains of mice.

In the brain, AQPs have important roles in

controlling water content (17,25).

Six types of AQP have been revealed to be expressed in the brain,

of which AQP4 was the most extensively studied, and proved to be

predominantly associated with cerebral edema (18–20).

To verify whether the brain mass was maintained by energy

adaptation or by increasing the water content in the cerebral

cells, the water content and expression levels of edema marker

proteins, AQP1 and 4, were detected (26). Whether water or food-deprived,

water content was not significantly affected. Therefore, cerebral

edema was not present during the course of water or/and food

shortage. Furthermore, compared with the control group, the

expression levels of AQP1 and 4 in the group deprived of both water

and food were only reduced on the third day. Alterations in AQP1

and 4 expression levels were similar, and were associated with

brain water content. On the fourth day, the expression levels of

both AQP1 and 4 reduced in the water and food deprivation group. In

addition, brain water content was also reduced in the water and

food deprivation group. Therefore, the mouse brain maintained its

normal water content via regulated expression of AQP1 and 4. The

brain may not only compete for energy with peripheral tissues in a

selfish way, but also compete for water via AQPs.

The mice brain maintained its water supply under

water shortage conditions in the same manner as energy regulation,

by selfishly obtaining the energy of other organs (24). However, could the brain draw energy

from its own cellular substances in an unselfish way? To answer the

question, the autophagy levels in the mice brain were determined

under the deprivation of water and/or food. The protein expression

levels of LC3 were used as a biomarker to measure the mouse brain

autophagic levels (22,27). The results in the present study

demonstrated that, both water and food shortage were able to

activate autophagy in cerebral cells. Among the deprivation

factors, food had an important role in activating autophagy in the

early period. As previous studies noted, autophagy is the major

mechanism underlying the degradation of long-lived proteins and the

only known signaling pathway responsible for the degradation of

organelles (21,28). In addition, autophagy was regulated

by nutritional status, hormonal factors and other factors including

temperature, oxygen concentrations and ultraviolet radiation

(29,30). Autophagy is a process associated

with energy re-usage in cells, and therefore food shortage may

affect autophagy more directly and apparently compared with water

shortage. Although the water content is less important for energy

metabolism compared with food intake, long-term water shortage also

caused functional disorders of the mice and the degradation of

proteins in cerebral cells, which finally lead to the activation of

autophagy. Therefore, in addition to competing with the energy of

other organs, the cerebral cells may also use their own substance

and energy resources through autophagy under harsh conditions,

which complement the traditional 'selfish brain' theory (10).

In conclusion, the present study further elucidated

the 'selfish brain' theory of water content maintenance via AQP1

and 4. In addition, unlike the traditional selfish theory, the

mouse brains were also demonstrated to obtain energy through

autophagy, which may be considered as an unselfish method. AQPs as

well as their regulatory signaling pathways merit further research

to clarify the role of water content in the brain.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by grants from the

General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China

(grant nos. 31300703 and 81271206), the National Basic Research

Project (program 973; grant no. 2012CB518200), the High-Technology

Program of China (program 863; grant no. 2012AA022402), the

National Key Technologies R&D Program for New Drugs of China

(grant no. 2012ZX09102301-016), The General Program of Basic

Research Project of Science and Technology of Jiangsu Province

(grant no. BK2012640), the Special Program of Science and

Technology Development of Suzhou of Jiangsu Province (grant no.

ZXY2012017) and the State Key Laboratory of Proteomics of China

(grant nos. SKLP-K201004, SKLP-Y201105, SKLP-0201104 and

SKLP-0201002).

References

|

1

|

Peters A, Pellerin L, Dallman M, Oltmanns

KM, Schweiger U, Born J and Fehm HL: Causes of obesity: Looking

beyond the hypothalamus. Prog Neurobiol. 81:61–88. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shulman RG, Rothman DL, Behar KL and Hyder

F: Energetic basis of brain activity: Implications for

neuroimaging. Trends Neurosci. 27:489–495. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bélanger M, Allaman I and Magistretti PJ:

Brain energy metabolism: Focus on astrocyte-neuron metabolic

cooperation. Cell Metab. 14:724–738. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Brown AM and Ransom BR: Astrocyte glycogen

and brain energy metabolism. Glia. 55:1263–1271. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Rosenblatt F: The perceptron: A

probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the

brain. Psychol Rev. 65:386–408. 1958. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Erecinska M, Cherian S and Silver IA:

Energy metabolism in mammalian brain during development. Prog

Neurobiol. 73:397–445. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ebert D, Haller RG and Walton ME: Energy

contribution of octanoate to intact rat brain metabolism measured

by 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurosci.

23:5928–5935. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Peters A, Schweiger U, Pellerin L, Hubold

C, Oltmanns KM, Conrad M, Schultes B, Born J and Fehm HL: The

selfish brain: Competition for energy resources. Neurosci Biobehav

Rev. 28:143–180. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Peters A, Schweiger U, Fruhwald-Schultes

B, Born J and Fehm HL: The neuroendocrine control of glucose

allocation. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 110:199–211. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hitze B, Hubold C, Van Dyken R,

Schlichting K, Lehnert H, Entringer S and Peters A: How the selfish

brain organizes its supply and demand. Fron Neuroenergetics.

2(7)2010.

|

|

11

|

Kennedy GC: The role of depot fat in the

hypothalamic control of food intake in the rat. Proc R Soc Lond B

Biol Sci. 140:578–596. 1953. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ahima RS, Prabakaran D, Mantzoros C, Qu D,

Lowell B, Maratos-Flier E and Flier JS: Role of leptin in the

neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature. 382:250–252. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lord GM, Matarese G, Howard JK, Baker RJ,

Bloom SR and Lechler RI: Leptin modulates the T-cell immune

response and reverses starvation-induced immunosuppression. Nature.

394:897–901. 1998. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ahima RS, Saper CB, Flier JS and Elmquist

JK: Leptin regulation of neuroendocrine systems. Front

Neuroendocrinol. 21:263–307. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mayer J: Regulation of energy intake and

the body weight: The glucostatic theory and the lipostatic

hypothesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 63:15–43. 1955. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kubera B, Hubold C, Zug S, Wischnath H,

Wilhelm I, Hallschmid M, Entringer S, Langemann D and Peters A: The

brain's supply and demand in obesity. Front Neuroenergetics.

4(4)2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Badaut J, Fukuda AM, Jullienne A and Petry

KG: Aquaporin and brain diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1840.1554–1565. 2014.

|

|

18

|

Badaut J, Lasbennes F, Magistretti PJ and

Regli L: Aquaporins in brain: Distribution, physiology and

pathophysiology. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 22:367–378. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Papadopoulos MC and Verkman AS:

Aquaporin-4 and brain edema. Pediatr Nephrol. 22:778–784. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Suzuki R, Okuda M, Asai J, Nagashima G,

Itokawa H, Matsunaga A, Fujimoto T and Suzuki T: Astrocytes

co-express aquaporin-1,-4 and vascular endothelial growth factor in

brain edema tissue associated with brain contusion. Acta Neurochir

Suppl. 96:398–401. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Henell F, Berkenstam A, Ahlberg J and

Glaumann H: Degradation of short-and long-lived proteins in

perfused liver and in isolated autophagic vacuoles-lysosomes. Exp

Mol Pathol. 46:1–14. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tanida I, Minematsu-Ikeguchi N, Ueno T and

Kominami E: Lysosomal turnover, but not a cellular level, of

endogenous LC3 is a marker for autophagy. Autophagy. 1:84–91. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shen Z, Qu W, Wang W, Lu Y, Wu Y, Li Z,

Hang X, Wang X, Zhao D and Zhang C: MPprimer: A program for

reliable multiplex PCR primer design. BMC Bioinformatics.

11(143)2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Fehm HL, Kern W and Peters A: The selfish

brain: Competition for energy resources. Prog Brain Res.

153:129–140. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tait MJ, Saadoun S, Bell BA and

Papadopoulos MC: Water movements in the brain: Role of aquaporins.

Trends Neurosci. 31:37–43. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Griesdale DE and Honey CR: Aquaporins and

brain edema. Surg Neurol. 61:418–421. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kuma A, Matsui M and Mizushima N: LC3, an

autophagosome marker, can be incorporated into protein aggregates

independent of autophagy: Caution in the interpretation of LC3

localization. Autophagy. 3:323–328. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mizushima N and Klionsky DJ: Protein

turnover via autophagy: Implications for metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr.

27:19–40. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shintani T and Klionsky DJ: Autophagy in

health and disease: A double-edged sword. Science. 306:990–995.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Chen Y, McMillan-Ward E, Kong J, Israels S

and Gibson S: Oxidative stress induces autophagic cell death

independent of apoptosis in transformed and cancer cells. Cell

Death Differ. 15:171–182. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|