The health risk assessment of environmental

selenium, concerning both abnormally low and high intakes, and the

related regulatory guidelines are generally based on ‘old’

evidence, since they have generally been unable to take into

consideration the most recent epidemiologic and biochemical

evidence, and particularly the recent results of large and

well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (1–3). The

results of these trials, in connection with biochemical and

toxicological studies, have shed new light on this relevant public

health issue. This has happened with reference to both the upper

and the lower limits of selenium intake, which have been so far

based in all the assessment on observational studies carried out in

seleniferous Chinese areas during the 1980s (4,5). The

availability of the experimental studies (the trials) is of

particular importance, since they allowed to rule out the key issue

of (unmeasured) confounding, typically affecting most of

observational studies with the possible only exception of the so

called ‘natural experiments’ (6).

In addition, the recent observational and experimental studies made

it possible to investigate different populations with reference to

age, genetic background and life-style factors, also allowing to

test the health effect of selective exposure to specific selenium

compounds, such as inorganic haxavalent selenium (selenate) and an

organic form, selenomethionine. This is particularly important

since there is growing evidence of the key importance of the

specific selenium forms in influencing the biological activity of

this element, with reference to both its toxicological and

nutritional effects (7–11).

A very large number of epidemiologic studies

assessed the relation between chronic exposure to environmental

selenium and human health. The studies on this issue frequently

investigated the effect on human health of unusually low or high

environmental exposures to selenium, due to an abnormal selenium

content in soil, locally produced foods and drinking water, or

following combustion of coal with high selenium content (5,12,13).

In addition, the scientific literature encompasses a large number

of nutritional epidemiology studies on the long-term health effects

of selenium carried out in populations living in non-seleniferous

regions and countries. These studies include experimental

investigations (randomized controlled trials) and observational

studies, the latter characterized by case-control, cohort,

cross-sectional and ecologic design and being characterized by a

far weaker ability compared with trials in addressing the selenium

and health relation (1,14,15).

While the entire review of this huge literature goes beyond the

possibility of this report, we aim at briefly updating the evidence

generated by the most recent environmental and nutritional studies

on the human health effects of selenium, the biological

plausibility of this relation, an overview of the challenges that

these studies and their interpretation pose, and finally their

implications on the adequacy of current environmental selenium

standards. Our update of this issue starts from the comprehensive

assessments of selenium exposure carried out by the US Institute of

Medicine in 2000 (4) and by a

World Health Organization (WHO) working group in 2004 (16).

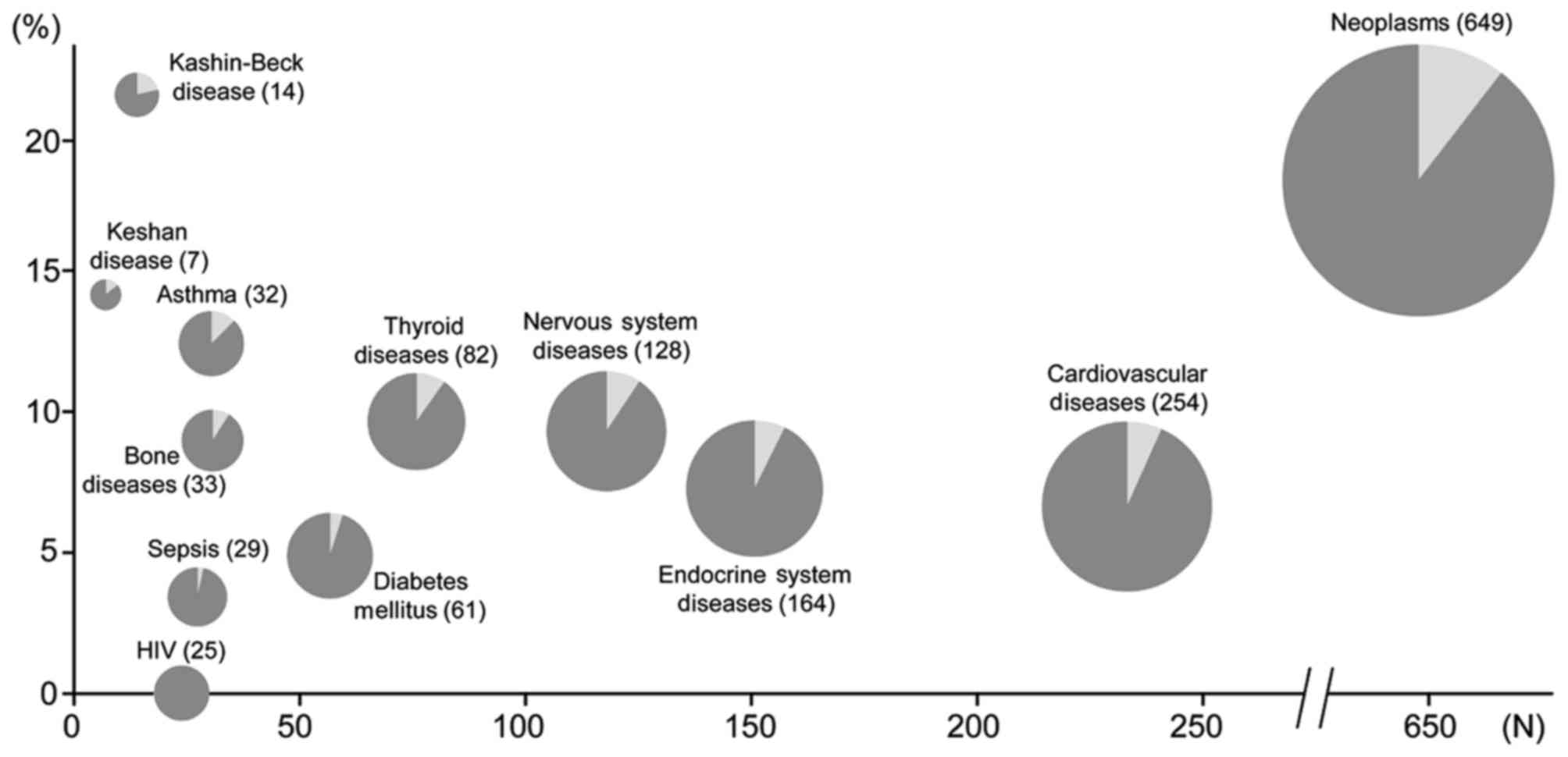

A large number of environmental studies which

investigated the health effects of unusually high or low selenium

areas have been published, as summarized in Table I. These studies have also

substantially contributed to the PubMed-indexed papers on the

epidemiology of selenium and human health in addition to the

previous papers (Fig. 1), adding

relevant data to our understanding of the health effects of

selenium in humans. Some of these studies have been published after

the 2000 Institute of Medicine selenium assessment (4), considerably extending the limited

evidence previously available on the basis of a few ‘old’ Chinese

studies. This literature includes the investigation of health

effects of high-selenium environment in South and North America,

India, China, and Italy. The high content of selenium in these

areas, in most cases of geological origin, has induced unusually

high levels of selenium in locally grown foodstuffs and

occasionally in outdoor air and in drinking water, thus increasing

human exposure to the element. However, systematic investigations

of the health effects of such exposures are unfortunately limited,

and in most cases they came from cross-sectional studies, and very

rarely from studies with a more adequate design, such as

case-control and particularly cohort studies. In addition, the

observational design of these studies induces in most cases a major

concern, the potential bias arising from unmeasured (dietary and

life-style) confounding, in addition to the potential issue of

exposure misclassification. Moreover, health endpoints were

generally different in these studies, thus not allowing their

systematic analysis (and meta-analysis) in the different

populations. Finally, in several cases the small number of exposed

subjects made it impossible to compute statistically stable

estimates, and this lack of precision hampered the detection of

potential health effects of such abnormally low and high exposures

to environmental selenium.

Overall, these studies have yielded an indication

that the extremely low selenium intake, in the order of <10-15

µg/day, may increase the risk of a severe cardiomyopathy named

‘Keshan disease’ (17–20), while high selenium intake may have

unfavorable effects on the endocrine system and particularly on the

thyroid status (21), and increase

the risk of type 2 diabetes (3,22,23),

some specific cancers such as melanoma and lymphoid cancers

(24–26), and nervous system disturbances

including alterations in visual evoked potentials (27) and excess risk of amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis (26,28).

Studies in populations with ‘intermediate’ selenium

status. Several studies have investigated the effects on human

health of even limited changes in exposure to environmental

selenium, which occurs through different environmental sources

(primarily diet, but also air pollution, occupational environment,

smoking and drinking water), in populations characterized by

exposure levels not considered a priori to be unusually

‘low’ or ‘high’ (14). These

studies, generally carried out in Western populations, have

investigated a broad number of health outcomes, but in the majority

of cases they focused on cancer risk (14,15).

However, most of these studies had an observational design, thus

suffering from the potential severe bias due to unmeasured

confounding and exposure misclassification even in prospective

cohort studies, in addition to the other biases typically effecting

studies with case-control, cross-sectional and clearly ecologic

design (1,14,29).

In addition, their results have frequently been conflicting even

for the same cancer type, as shown for instance for liver cancer

(30,31), lung cancer (32–34)

or breast cancer (35–38), though in most cases they supported

the occurrence of an inverse relation between selenium status and

cancer risk (1). Luckily and

rather unexpectedly for a nutrient with also was known to exert a

powerful toxicity, the nutritional interest in this metalloid as

well as the extremely ‘attractive’ preliminary results of the first

selenium trial carried out in Western countries, the Nutrition

Prevention of Cancer (NPC) trial (39), a large number of randomized

controlled trials have been conducted during the last two decades.

The aim of these studies has been to investigate the effects on

cancer risk of an increased intake of this element (1,40).

Overall, all the recent trials have consistently

shown that selenium does not modify risk of overall cancer,

prostate cancer and other specific cancers (2,3,23,43–45),

while it may even increase risk of cancers such as advanced

(46,47) or overall prostate cancer (48), non-melanoma skin cancer (49,50)

and possibly breast cancer in high-risk women (51). These results strongly and

unexpectedly differ from the results reported in the earliest

trial, the NPC (49,52), which however was small and more

importantly was later found to be affected by a detection bias

(53). As previously mentioned,

these trials have also been of fundamental (and unforeseen)

importance in identifying the early signs, symptoms and diseases

associated with chronic or subchronic selenium toxicity. In fact,

they have shown that already at amount of selenium exposure

(baseline dietary intake plus supplementation) of around 250–300

µg/day there is an increased risk of type-2 diabetes. Such excess

diabetes risk linked to selenium overexposure was first discovered

in trial carried out in a population with a ‘low’ baseline selenium

status (15,22) and later confirmed in large trials

(3,23). Finally, the largest of the selenium

RCTs, SELECT (23), whose overall

selenium intake in the supplemented group averaged 300 µg/day

(15), has shown that such amount

of exposure induces ‘minor’ adverse effects such as dermatitis and

alopecia [a long-recognized sign of selenium toxicity (12)]. These effects indicate that the

selenium lower-observed-adverse-effect-level (LOAEL) is much lower

than previously considered by regulatory agencies (5,54),

which could base their assessment on the scarce data yielded by a

few old Chinese environmental studies (55), calling for an update of the risk

assessment of this element (5,15,56,57).

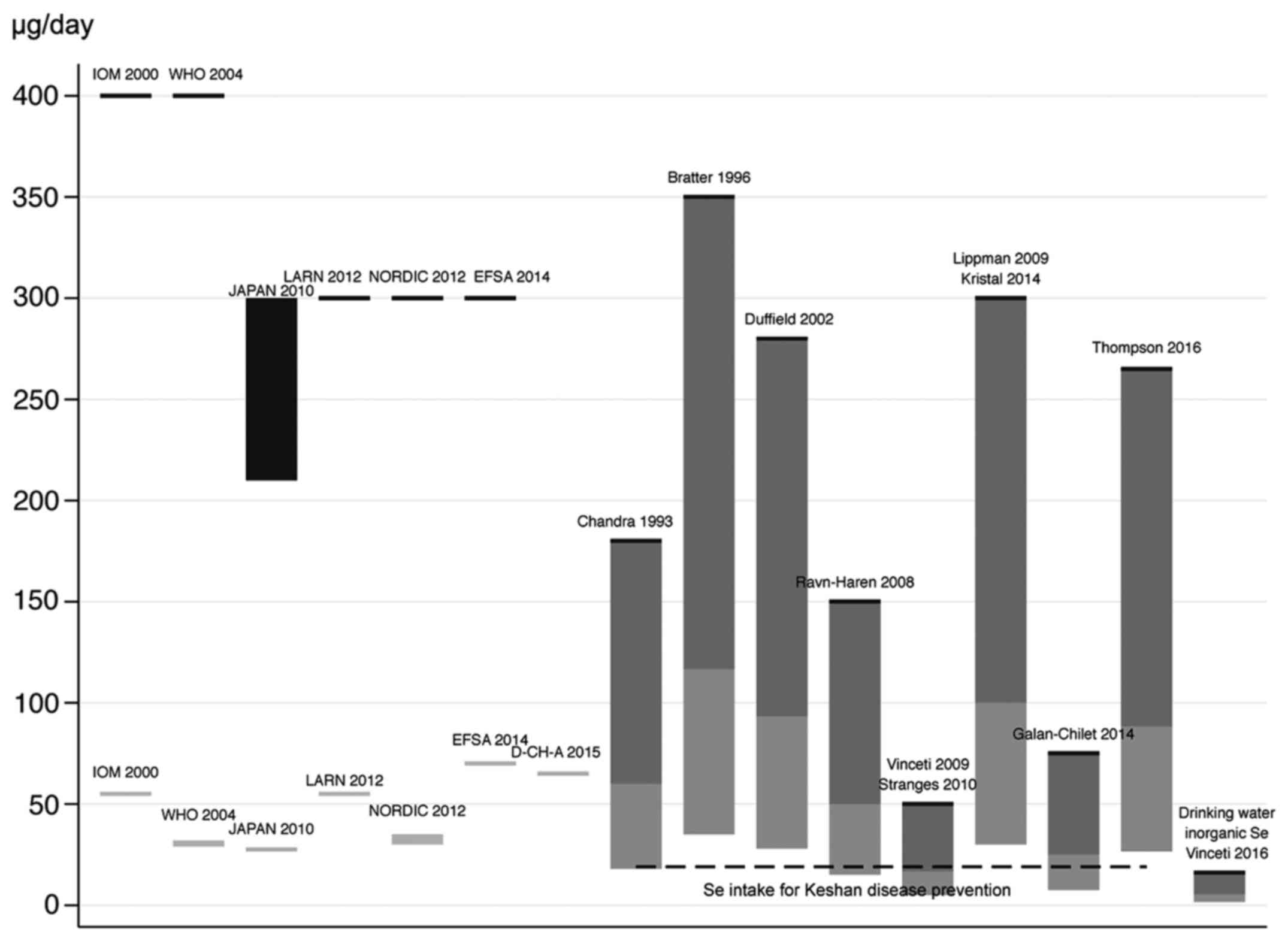

An issue therefore arises about the adequacy of

current standards for environmental risk assessment of selenium in

the human, for both abnormally low and high exposures. These

standards have been defined by a number of agencies since 2000 to

2014, and as summarized in Fig. 2

they encompass minimal recommended values ranging from 30 to 70

µg/day, and upper doses ranging from 300 to 400 µg/day (in adults)

for overall selenium exposure (4,16,58–61).

On the contrary, specific guidelines for single selenium species

have not been unfortunately set, despite the clear evidence that

the various chemical forms of selenium have different biological

properties, i.e. nutritional and toxicological activities (7,9,10,62).

So far, the adequacy of the selenium standards has

been mainly based on biochemical endpoints (for the lowest

recommended intake) and on the occurrence of adverse health

outcomes (for the upper level), as identified in old studies

carried out in seleniferous areas from China. However, the newly

available data from the clinical trials indicate the need of a

substantial reassessment of the dose of selenium toxicity, though

they unfortunately do not allow to clearly identify a NOAEL and

probably also a reliable LOAEL, since only one supplemental dose

(200 µg/selenium/day) have been used in these trials and

dose-response data are lacking. However, using an uncertainty

factor as little as 3, i.e. lower that the uncertainty factors

usually adopted in risk assessment (10 or more) also in light of

the peculiar nature of this element and its nutritional relevance,

selenium intake should not exceed 90 µg/day taking into account the

signs of toxicity yielded by the NPC trial (an excess diabetes and

skin cancer risk) and by the SELECT trial (an excess incidence of

diabetes, advanced prostate cancer, dermatitis and alopecia)

(1), as shown in Fig. 2. However, this estimate may be

still inadequate to protect human health from chronic selenium

toxicity, and in addition it appears to apply only to organic

selenium, and to selenomethionine in particular [whose toxicity has

bene recently much better elucidated (63–65)].

For inorganic selenium, typically selenate such as

those found in underground and drinking waters, the epidemiologic

evidence points to a much higher toxicity compared with organic

selenium and exactly as expected on the basis of experimental

studies (10), therefore

suggesting much lower acceptable environmental standards (57), tentatively 1 µg/l for drinking

water (5). New standards should

also be considered for occupational exposure to selenium, given the

limited data available and the potential for toxicity of this

source of exposure (12,13,66,67).

Finally, air selenium might represent a so far overlooked risk

factor for chronic diseases, taking into account that its outdoor

air concentrations have been positively associated with

cardiovascular mortality (68) and

with childhood leukemia risk (69), though more evidence is clearly

required to confirm such possible associations mainly due to the

inherent risk of unmeasured confounding in these observational

studies.

The lowest acceptable amount of selenium exposure is

instead much more controversial and uncertain. Two approaches have

been used to define such lowest safe level of exposure: the

proteomic change induced by the trace element, and the avoidance of

adverse health effects. Concerning the latter point (health

issues), still limited and inconclusive evidence is available on

the large number of diseases tentatively ascribed to a deficiency

of environmental selenium (4,70),

such as the chronic degenerative osteoarthropathy with unclear

etiology named ‘Kashin-Beck’ disease (71,72)

and an increased susceptibility to viral infections (73,74).

In addition, the hypothesis of an effect of ‘low’

environmental selenium exposure in increasing cancer risk may now

be ruled out, thanks to the consistent evidence yielded by the

recent large and well-conducted randomized trials, which ruled out

any preventive effect of selenium on cancer risk. On the converse,

evidence exists on the involvement of selenium deficiency on the

etiology of a rare but severe cardiomyopathy named Keshan disease

and endemic in some Chinese areas (17,18,20,75–77),

and this observation has played a key role in the identification of

the minimal amount of selenium which appears to be required in

humans (4,78). Such involvement has been suggested

mainly on the basis of observational evidence, i.e. a lower

selenium status in the populations more affected by this disease,

and following the beneficial effects of a selenium supplementation

trial on disease incidence.

However, some epidemiologic features of the disease

have since the discovery of the disease suggested alternative

etiologic hypotheses (79),

particularly a cardiotropic infectious agent such as a Coxsackie

virus, selenium deficiency possibly being a cofactor in disease

etiology or simply an innocent bystander (19,20,54,77).

Under this perspective, the beneficial effect of selenium

supplementation in a Chinese trial might be interpreted as an

indication of antiviral effects of the selenium compound used

(inorganic tetravalent selenium, i.e. selenite), as suggested by

laboratory studies (40,80). In any case, while still

investigating the cause of Keshan disease and the possible

involvement of selenium status, it is prudent to avoid a too low

intake of selenium under the hypothesis of a role in Keshan disease

etiology, and therefore average population intake must be higher

than that shown to be required to avoid disease incidence, i.e.

13.3 µg/day in females and 19.1 in males (16). Finally, recent evidence has

suggested adverse health effects of mutations affecting Sec

insertion sequence-binding protein 2 or the selenoprotein N1 gene

(81–83), though such abnormalities might not

be strictly related to a ‘selenium deficiency’ neither were they

corrected by its supplementation (84), thus being of limited interest in

the setting of minimal dietary selenium requirements.

Alternatively, to the use of health endpoints, and

considerably more frequently, the amount of the selenium needed to

induce the maximization of selenoprotein synthesis (particularly

glutathione-peroxidase and plasma selenoprotein P) has been

proposed to set the minimal requirement of selenium in the human.

This approach has been based on the assumption that achievement of

this biochemical endpoint, i.e. upregulation (frequently defined as

‘optimization’) of selenoprotein synthesis indicates the

achievement of an adequate supply of this trace element to the

human (40,85). This would point to adequate dietary

intake (considering this as only source of selenium exposure) of

amount in the order of 70 µg/day (85), thus reaching or even exceeding the

upper limit definable on the basis of the SELECT trial results

using an uncertainty factor of 3 and clearly even more, of course,

when using an uncertainty factor of 10 (Fig. 2). In addition, this ‘biochemical’

approach does not take into account that selenoprotein maximization

which follows selenium species administration may derive not just

from the ‘correction’ of a nutritional deficiency of the trace

element, but as a compensatory response of these proteins (all

characterized by antioxidant properties) to the pro-oxidant

activity of selenium species (40,54,86–94).

There is also little evidence showing that

selenoprotein activity, and particularly its maximization, are

beneficial to human health, and therefore (as more generally levels

for antioxidant enzymes) this should not be regarded as an

objective unless more evidence in humans are provided (40,54).

This approach is further strengthened when taking into account that

these enzymes are physiologically induced and inducible by

oxidative stress (for selenoproteins, even in the absence of any

change in selenium supply) (40,54),

as long recognized since the discovery of the selenium-containing

antioxidant enzyme glutathione-peroxidase (95–97).

Overall, it seems therefore prudent to avoid a maximal expression

of selenoproteins (54,98), setting as standard a lower amount

of their activity, such as proposed by WHO when suggesting a

‘nutritionally adequate’ target (‘recommended nutrient intake’) the

achievement of two thirds of the maximal selenoprotein activity,

corresponding to a daily selenium intake of 25–34 µg in adults

(Fig. 2). However, more research

is clearly required to set reliable lower and upper safe selenium

levels, though the current standards need to be quickly updated

with reference to the upper levels taking into account the

above-mentioned recent results of the epidemiologic studies, i.e.

the high-quality RCTs and the environmental studies, and also

considering the opportunity to set species-specific standards for

this element.

|

1

|

Vinceti M, Dennert G, Crespi CM, Zwahlen

M, Brinkman M, Zeegers MP, Horneber M, D'Amico R and Del Giovane C:

Selenium for preventing cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

3:CD0051952014.

|

|

2

|

Lance P, Alberts DS, Thompson PA, Fales L,

Wang F, Jose San J, Jacobs ET, Goodman PJ, Darke AK, Yee M, et al:

Colorectal adenomas in participants of the SELECT randomized trial

of selenium and vitamin E for prostate cancer prevention. Cancer

Prev Res (Phila). 10:45–54. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Thompson PA, Ashbeck EL, Roe DJ, Fales L,

Buckmeier J, Wang F, Bhattacharyya A, Hsu CH, Chow HH, Ahnen DJ, et

al: Selenium supplementation for prevention of colorectal adenomas

and risk of associated type 2 diabetes. J Natl Cancer Inst.

108:pii: djw152. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Institute of Medicine Food and Nutrition

Board: Dietary references intakes for vitamin C, vitamin E,

selenium, and carotenoids. National Academy Press; Washington, DC:

2000

|

|

5

|

Vinceti M, Crespi CM, Bonvicini F,

Malagoli C, Ferrante M, Marmiroli S and Stranges S: The need for a

reassessment of the safe upper limit of selenium in drinking water.

Sci Total Environ. 443:633–642. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rothman KJ, Greenland S and Lash TL:

Modern Epidemiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;

Philadelphia: 2012, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Michalke B, Halbach S and Nischwitz V: JEM

spotlight: Metal speciation related to neurotoxicity in humans. J

Environ Monit. 11:939–954. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gammelgaard B, Jackson MI and Gabel-Jensen

C: Surveying selenium speciation from soil to cell--forms and

transformations. Anal Bioanal Chem. 399:1743–1763. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Weekley CM and Harris HH: Which form is

that? The importance of selenium speciation and metabolism in the

prevention and treatment of disease. Chem Soc Rev. 42:8870–8894.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Vinceti M, Solovyev N, Mandrioli J, Crespi

CM, Bonvicini F, Arcolin E, Georgoulopoulou E and Michalke B:

Cerebrospinal fluid of newly diagnosed amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis patients exhibits abnormal levels of selenium species

including elevated selenite. Neurotoxicology. 38:25–32. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Vinceti M, Grill P, Malagoli C, Filippini

T, Storani S, Malavolti M and Michalke B: Selenium speciation in

human serum and its implications for epidemiologic research: A

cross-sectional study. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 31:1–10. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Vinceti M, Wei ET, Malagoli C, Bergomi M

and Vivoli G: Adverse health effects of selenium in humans. Rev

Environ Health. 16:233–251. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Vinceti M, Mandrioli J, Borella P,

Michalke B, Tsatsakis A and Finkelstein Y: Selenium neurotoxicity

in humans: Bridging laboratory and epidemiologic studies. Toxicol

Lett. 230:295–303. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Vinceti M, Crespi CM, Malagoli C, Del

Giovane C and Krogh V: Friend or foe? The current epidemiologic

evidence on selenium and human cancer risk. J Environ Sci Health C

Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev. 31:305–341. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Vinceti M, Burlingame B, Fillippini T,

Naska A, Bargellini A and Borella P: The epidemiology of selenium

and human healthSelenium: Its Molecular Biology and Role in Human

Health. Hatfield D, Schweizer U and Gladyshev VN: 4th. Springer

Science Business Media; New York: pp. 365–376. 2016, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Human

Vitamin and Mineral Requirements: Vitamin and mineral requirements

in human nutrition. 2nd. World Health Organization and Food and

Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Geneva: 2004

|

|

17

|

Keshan Disease Research Group of the

Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences: Epidemiologic studies on the

etiologic relationship of selenium and Keshan disease. Chin Med J

(Engl). 92:477–482. 1979.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Keshan Disease Research Group of the

Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences: Observations on effect of

sodium selenite in prevention of Keshan disease. Chin Med J (Engl).

92:471–476. 1979.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wang T and Li Q: Interpretation of

selenium deficiency and Keshan disease with causal inference of

modern epidemiologyThe 5th International Selenium Seminar.

Organizing Committee of the International Selenium Seminar; Moscow:

pp. 34–35. 2015

|

|

20

|

Lei C, Niu X, Ma X and Wei J: Is selenium

deficiency really the cause of Keshan disease? Environ Geochem

Health. 33:183–188. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Winther KH, Bonnema SJ, Cold F, Debrabant

B, Nybo M, Cold S and Hegedüs L: Does selenium supplementation

affect thyroid function? Results from a randomized, controlled,

double-blinded trial in a Danish population. Eur J Endocrinol.

172:657–667. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Stranges S, Marshall JR, Natarajan R,

Donahue RP, Trevisan M, Combs GF, Cappuccio FP, Ceriello A and Reid

ME: Effects of long-term selenium supplementation on the incidence

of type 2 diabetes: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med.

147:217–223. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia

MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Minasian LM, Gaziano JM,

Hartline JA, et al: Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of

prostate cancer and other cancers: The Selenium and Vitamin E

Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 301:39–51. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Vinceti M, Rovesti S, Gabrielli C,

Marchesi C, Bergomi M, Martini M and Vivoli G: Cancer mortality in

a residential cohort exposed to environmental selenium through

drinking water. J Clin Epidemiol. 48:1091–1097. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Vinceti M, Rothman KJ, Bergomi M, Borciani

N, Serra L and Vivoli G: Excess melanoma incidence in a cohort

exposed to high levels of environmental selenium. Cancer Epidemiol

Biomarkers Prev. 7:853–856. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Vinceti M, Ballotari P, Steinmaus C,

Malagoli C, Luberto F, Malavolti M and Rossi Giorgi P: Long-term

mortality patterns in a residential cohort exposed to inorganic

selenium in drinking water. Environ Res. 150:348–356. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Saint-Amour D, Roy MS, Bastien C, Ayotte

P, Dewailly E, Després C, Gingras S and Muckle G: Alterations of

visual evoked potentials in preschool Inuit children exposed to

methylmercury and polychlorinated biphenyls from a marine diet.

Neurotoxicology. 27:567–578. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Vinceti M, Bonvicini F, Rothman KJ,

Vescovi L and Wang F: The relation between amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis and inorganic selenium in drinking water: A

population-based case-control study. Environ Health. 9:772010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Vinceti M and Rothman KJ: More results but

no clear conclusion on selenium and cancer. Am J Clin Nutr.

104:245–246. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hughes DJ, Duarte-Salles T, Hybsier S,

Trichopoulou A, Stepien M, Aleksandrova K, Overvad K, Tjønneland A,

Olsen A, Affret A, et al: Prediagnostic selenium status and

hepatobiliary cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation

into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 104:406–414.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ma X, Yang Y, Li HL, Zheng W, Gao J, Zhang

W, Yang G, Shu XO and Xiang YB: Dietary trace element intake and

liver cancer risk: Results from two population-based cohorts in

China. Int J Cancer. 140:1050–1059. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Knekt P, Marniemi J, Teppo L, Heliövaara M

and Aromaa A: Is low selenium status a risk factor for lung cancer?

Am J Epidemiol. 148:975–982. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, van't Veer

P, Bode P, Dorant E, Hermus RJ and Sturmans F: A prospective cohort

study on selenium status and the risk of lung cancer. Cancer Res.

53:4860–4865. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Suadicani P, Hein HO and Gyntelberg F:

Serum selenium level and risk of lung cancer mortality: A 16-year

follow-up of the Copenhagen Male Study. Eur Respir J. 39:1443–1448.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Menkes MS, Comstock GW, Vuilleumier JP,

Helsing KJ, Rider AA and Brookmeyer R: Serum beta-carotene,

vitamins A and E, selenium, and the risk of lung cancer. N Engl J

Med. 315:1250–1254. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

van Noord PA, Maas MJ, van der Tweel I and

Collette C: Selenium and the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer

in the DOM cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 25:11–19. 1993.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, van't Veer

P, Bode P, Dorant E, Hermus RJ and Sturmans F: Toenail selenium

levels and the risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 140:20–26.

1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Garland M, Morris JS, Stampfer MJ, Colditz

GA, Spate VL, Baskett CK, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Willett WC and

Hunter DJ: Prospective study of toenail selenium levels and cancer

among women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 87:497–505. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Clark LC, Combs GFJ Jr, Turnbull BW, Slate

EH, Chalker DK, Chow J, Davis LS, Glover RA, Graham GF, Gross EG,

et al: Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group: Effects of

selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with

carcinoma of the skin. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA.

276:1957–1963. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Jablonska E and Vinceti M: Selenium and

Human Health: Witnessing a Copernican Revolution? J Environ Sci

Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev. 33:328–368. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Higgins JP: A revised tool to assess risk

of bias in randomized trials. (RoB 2.0). 2016.

|

|

42

|

Rees K, Hartley L, Day C, Flowers N,

Clarke A and Stranges S: Selenium supplementation for the primary

prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

1:CD0096712013.

|

|

43

|

Stratton MS, Reid ME, Schwartzberg G,

Minter FE, Monroe BK, Alberts DS, Marshall JR and Ahmann FR:

Selenium and prevention of prostate cancer in high-risk men: The

Negative Biopsy Study. Anticancer Drugs. 14:589–594. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Algotar AM, Stratton MS, Ahmann FR,

Ranger-Moore J, Nagle RB, Thompson PA, Slate E, Hsu CH, Dalkin BL,

Sindhwani P, et al: Phase 3 clinical trial investigating the effect

of selenium supplementation in men at high-risk for prostate

cancer. Prostate. 73:328–335. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Karp DD, Lee SJ, Keller SM, Wright GS,

Aisner S, Belinsky SA, Johnson DH, Johnston MR, Goodman G, Clamon

G, et al: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III

chemoprevention trial of selenium supplementation in patients with

resected stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: ECOG 5597. J Clin

Oncol. 31:4179–4187. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kristal AR, Darke AK, Morris JS, Tangen

CM, Goodman PJ, Thompson IM, Meyskens FL Jr, Goodman GE, Minasian

LM, Parnes HL, et al: Baseline selenium status and effects of

selenium and vitamin e supplementation on prostate cancer risk. J

Natl Cancer Inst. 106:djt4562014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Albanes D, Till C, Klein EA, Goodman PJ,

Mondul AM, Weinstein SJ, Taylor PR, Parnes HL, Gaziano JM, Song X,

et al: Plasma tocopherols and risk of prostate cancer in the

Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). Cancer

Prev Res (Phila). 7:886–895. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Martinez EE, Darke AK, Tangen CM, Goodman

PJ, Fowke JH, Klein EA and Abdulkadir SA: A functional variant in

NKX3.1 associated with prostate cancer risk in the Selenium and

Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). Cancer Prev Res

(Phila). 7:950–957. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Duffield-Lillico AJ, Slate EH, Reid ME,

Turnbull BW, Wilkins PA, Combs GF Jr, Park HK, Gross EG, Graham GF,

Stratton MS, et al: Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group:

Selenium supplementation and secondary prevention of nonmelanoma

skin cancer in a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst.

95:1477–1481. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Dréno B, Euvrard S, Frances C, Moyse D and

Nandeuil A: Effect of selenium intake on the prevention of

cutaneous epithelial lesions in organ transplant recipients. Eur J

Dermatol. 17:140–145. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Lubinski J, Jaworska K, Durda K,

Jakubowska A, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Stawicka M, Gronwald J, Górski

B, Wasowicz W, et al: Selenium and the risk of cancer in BRCA1

carriers. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 9:(Suppl 2). A52011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

52

|

Duffield-Lillico AJ, Reid ME, Turnbull BW,

Combs GFJ Jr, Slate EH, Fischbach LA, Marshall JR and Clark LC:

Baseline characteristics and the effect of selenium supplementation

on cancer incidence in a randomized clinical trial: A summary

report of the Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Trial. Cancer

Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 11:630–639. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Duffield-Lillico AJ, Dalkin BL, Reid ME,

Turnbull BW, Slate EH, Jacobs ET, Marshall JR and Clark LC:

Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group: Selenium

supplementation, baseline plasma selenium status and incidence of

prostate cancer: An analysis of the complete treatment period of

the Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Trial. BJU Int. 91:608–612.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Vinceti M, Maraldi T, Bergomi M and

Malagoli C: Risk of chronic low-dose selenium overexposure in

humans: Insights from epidemiology and biochemistry. Rev Environ

Health. 24:231–248. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yang GQ, Wang SZ, Zhou RH and Sun SZ:

Endemic selenium intoxication of humans in China. Am J Clin Nutr.

37:872–881. 1983.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Barron E, Migeot V, Rabouan S,

Potin-Gautier M, Séby F, Hartemann P, Lévi Y and Legube B: The case

for re-evaluating the upper limit value for selenium in drinking

water in Europe. J Water Health. 7:630–641. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Frisbie SH, Mitchell EJ and Sarkar B:

Urgent need to reevaluate the latest World Health Organization

guidelines for toxic inorganic substances in drinking water.

Environ Health. 14:632015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Scientific Committee on Food: Opinion of

the Scientific Committee on Food on the Tolerable Upper Intake

Level of SeleniumEuropean Commission. Brussels: 2000, https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/sci-com_scf_out80g_en.pdf

|

|

59

|

Tsubota-Utsugi M, Imai E, Nakade M,

Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Morita A and Tokudome S: Dietary Reference

Intakes for Japanese - 2010. The summary report from the Scientific

Committee of ‘Dietary Reference intakes for Japanese’National

Institute of Health and Nutrition. Japan: 2012

|

|

60

|

Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2012.

5th. Nordic Council of Ministers; Copenhagen: 2014, doi:

org/10.6027/Nord2014-002.

|

|

61

|

Società Italiana di Nutrizione Umana: LARN

- Livelli di assunzione di riferimento di nutrienti e energia per

la popolazione italiana - IV revisioneSICS. Milan: 2014, (In

Italian).

|

|

62

|

Marschall TA, Bornhorst J, Kuehnelt D and

Schwerdtle T: Differing cytotoxicity and bioavailability of

selenite, methylselenocysteine, selenomethionine, selenosugar 1 and

trimethylselenonium ion and their underlying metabolic

transformations in human cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 60:2622–2632.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Lazard M, Dauplais M, Blanquet S and

Plateau P: Trans-sulfuration pathway seleno-amino acids are

mediators of selenomethionine toxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

J Biol Chem. 290:10741–10750. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Raine JC, Lallemand L, Pettem CM and Janz

DM: Effects of chronic dietary selenomethionine exposure on the

visual system of adult and F1 generation zebrafish (Danio rerio).

Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 97:331–336. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Dolgova NV, Hackett MJ, MacDonald TC,

Nehzati S, James AK, Krone PH, George GN and Pickering IJ:

Distribution of selenium in zebrafish larvae after exposure to

organic and inorganic selenium forms. Metallomics. 8:305–312. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Göen T, Schaller B, Jäger T, Bräu-Dümler

Ch, Schaller KH and Drexler H: Biological monitoring of exposure

and effects in workers employed in a selenium-processing plant. Int

Arch Occup Environ Health. 88:623–630. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Jäger T, Drexler H and Göen T: Human

metabolism and renal excretion of selenium compounds after oral

ingestion of sodium selenate dependent on trimethylselenium ion

(TMSe) status. Arch Toxicol. 90:149–158. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Ito K, Mathes R, Ross Z, Nádas A, Thurston

G and Matte T: Fine particulate matter constituents associated with

cardiovascular hospitalizations and mortality in New York City.

Environ Health Perspect. 119:467–473. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Heck JE, Park AS, Qiu J, Cockburn M and

Ritz B: Risk of leukemia in relation to exposure to ambient air

toxics in pregnancy and early childhood. Int J Hyg Environ Health.

217:662–668. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Burk RF Jr: Selenium deficiency in search

of a disease. Hepatology. 8:421–423. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Yu FF, Liu H and Guo X: Integrative

multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for

Kashin-Beck disease. Biol Trace Elem Res. 174:274–279. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Yu FF, Zhang YX, Zhang LH, Li WR, Guo X

and Lammi MJ: Identified molecular mechanism of interaction between

environmental risk factors and differential expression genes in

cartilage of Kashin-Beck disease. Medicine (Baltimore).

95:e56692016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Beck MA, Levander OA and Handy J: Selenium

deficiency and viral infection. J Nutr. 133:(Suppl 1). 1463S–1467S.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Sheridan PA, Zhong N, Carlson BA, Perella

CM, Hatfield DL and Beck MA: Decreased selenoprotein expression

alters the immune response during influenza virus infection in

mice. J Nutr. 137:1466–1471. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Gu BQ: Pathology of Keshan disease. A

comprehensive review. Chin Med J (Engl). 96:251–261.

1983.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Levander OA and Beck MA: Interacting

nutritional and infectious etiologies of Keshan disease. Insights

from coxsackie virus B-induced myocarditis in mice deficient in

selenium or vitamin E. Biol Trace Elem Res. 56:5–21. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Xu GL, Wang SC, Gu BQ, Yang YX, Song HB,

Xue WL, Liang WS and Zhang PY: Further investigation on the role of

selenium deficiency in the aetiology and pathogenesis of Keshan

disease. Biomed Environ Sci. 10:316–326. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Chen J: An original discovery: Selenium

deficiency and Keshan disease (an endemic heart disease). Asia Pac

J Clin Nutr. 21:320–326. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Guanqing H: On the etiology of Keshan

disease: Two hypotheses. Chin Med J (Engl). 92:416–422.

1979.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Cermelli C, Vinceti M, Scaltriti E,

Bazzani E, Beretti F, Vivoli G and Portolani M: Selenite inhibition

of Coxsackie virus B5 replication: Implications on the etiology of

Keshan disease. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 16:41–46. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Schoenmakers E, Agostini M, Mitchell C,

Schoenmakers N, Papp L, Rajanayagam O, Padidela R, Ceron-Gutierrez

L, Doffinger R, Prevosto C, et al: Mutations in the selenocysteine

insertion sequence-binding protein 2 gene lead to a multisystem

selenoprotein deficiency disorder in humans. J Clin Invest.

120:4220–4235. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Scoto M, Cirak S, Mein R, Feng L, Manzur

AY, Robb S, Childs AM, Quinlivan RM, Roper H, Jones DH, et al:

SEPN1-related myopathies: Clinical course in a large cohort of

patients. Neurology. 76:2073–2078. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Ardissone A, Bragato C, Blasevich F,

Maccagnano E, Salerno F, Gandioli C, Morandi L, Mora M and Moroni

I: SEPN1-related myopathy in three patients: Novel mutations and

diagnostic clues. Eur J Pediatr. 175:1113–1118. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Schomburg L, Dumitrescu AM, Liao XH,

Bin-Abbas B, Hoeflich J, Köhrle J and Refetoff S: Selenium

supplementation fails to correct the selenoprotein synthesis defect

in subjects with SBP2 gene mutations. Thyroid. 19:277–281. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

EFSA NDA Panel: Scientific opinion on

dietary reference values for selenium. EFSA J. 12:38462014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Ge KY, Wang SQ, Bai J, Xue AN, Deng XJ, Su

CQ and Wu SQ: The protective effect of selenium against viral

myocarditis in miceSelenium in biology and medicine. Part B, Combs

GF, Spallholz JE, Levander OA and Oldfield JE: Avi Book, Van

Nostrand Reinhold Co.; New York: pp. 761–768. 1987

|

|

87

|

Spallholz JE: Free radical generation by

selenium compounds and their prooxidant toxicity. Biomed Environ

Sci. 10:260–270. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Stewart MS, Spallholz JE, Neldner KH and

Pence BC: Selenium compounds have disparate abilities to impose

oxidative stress and induce apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med.

26:42–48. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Letavayová L, Vlasáková D, Spallholz JE,

Brozmanová J and Chovanec M: Toxicity and mutagenicity of selenium

compounds in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat Res. 638:1–10. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Misra S, Boylan M, Selvam A, Spallholz JE

and Björnstedt M: Redox-active selenium compounds - from toxicity

and cell death to cancer treatment. Nutrients. 7:3536–3556. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Lee KH and Jeong D: Bimodal actions of

selenium essential for antioxidant and toxic pro-oxidant

activities: The selenium paradox (Review). Mol Med Rep. 5:299–304.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Brozmanová J, Mániková D, Vlčková V and

Chovanec M: Selenium: A double-edged sword for defense and offence

in cancer. Arch Toxicol. 84:919–938. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Schiar VP, Dos Santos DB, Paixão MW,

Nogueira CW, Rocha JB and Zeni G: Human erythrocyte hemolysis

induced by selenium and tellurium compounds increased by GSH or

glucose: A possible involvement of reactive oxygen species. Chem

Biol Interact. 177:28–33. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Guo CH, Hsia S, Hsiung DY and Chen PC:

Supplementation with selenium yeast on the prooxidant-antioxidant

activities and anti-tumor effects in breast tumor xenograft-bearing

mice. J Nutr Biochem. 26:1568–1579. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Hafeman DG, Sunde RA and Hoekstra WG:

Effect of dietary selenium on erythrocyte and liver glutathione

peroxidase in the rat. J Nutr. 104:580–587. 1974.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Oh SH, Sunde RA, Pope AL and Hoekstra WG:

Glutathione peroxidase response to selenium intake in lambs fed a

Torula yeast-based, artificial milk. J Anim Sci. 42:977–983. 1976.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Kramer GF and Ames BN: Mechanisms of

mutagenicity and toxicity of sodium selenite

(Na2SeO3) in Salmonella typhimurium. Mutat

Res. 201:169–180. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Macallan DC and Sedgwick P: Selenium

supplementation and selenoenzyme activity. Clin Sci (Lond).

99:579–581. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Tsongas TA and Ferguson SW: Selenium

concentrations in human urine and drinking waterProceedings of

‘Trace Elements in Man and Animal-3’. Kirchgessner N: Institute for

Nursing Physiology Technical University Munchen; Freising: pp.

320–321. 1978

|

|

100

|

Tsongas TA and Ferguson SW: Human health

effects of selenium in a rural Colorado drinking water supply. In:

Proceedings of ‘Trace substances in environmental health-XIA

symposium’. Hemphill DD: University of Missouri; Columbia: pp.

30–35. 1977

|

|

101

|

Valentine JL: Environmental occurrence of

selenium in waters and related health significance. Biomed Environ

Sci. 10:292–299. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Valentine JL, Kang HK, Dang PM and

Schluchter M: Selenium concentrations and glutathione peroxidase

activities in a population exposed to selenium via drinking water.

J Toxicol Environ Health. 6:731–736. 1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Valentine JL, Faraji B and Kang HK: Human

glutathione peroxidase activity in cases of high selenium

exposures. Environ Res. 45:16–27. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Valentine JL, Reisbord LS, Kang HK and

Schluchter M: Effects on human health of exposure to selenium in

drinking waterProceedings of ‘Selenium in Biology and Medicine -

Part B’. Combs GF, Levander OA, Spallholz JE and Oldfield JE: Van

Nostrand Reihold Co.; New York: pp. 675–687. 1987

|

|

105

|

Longnecker MP, Taylor PR, Levander OA,

Howe M, Veillon C, McAdam PA, Patterson KY, Holden JM, Stampfer MJ,

Morris JS, et al: Selenium in diet, blood, and toenails in relation

to human health in a seleniferous area. Am J Clin Nutr.

53:1288–1294. 1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Brätter P and de Negretti Brätter VE:

Influence of high dietary selenium intake on the thyroid hormone

level in human serum. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 10:163–166. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Fordyce FM, Zhan G, Green K and Liu X:

Soil, grain and water chemistry in relation to human

selenium-responsive diseases in Enshi District, China. Applied

Geochemistry. 15:117–132. 2000.doi: 10.1016/S0883-2927(99)00035-9.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Zhu J, Wang N, Li S, Li L, Su H and Liu C:

Distribution and transport of selenium in Yutangba, China: Impact

of human activities. Sci Total Environ. 392:252–261. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Hira CK, Partal K and Dhillon KS: Dietary

selenium intake by men and women in high and low selenium areas of

Punjab. Public Health Nutr. 7:39–43. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Lemire M, Fillion M, Frenette B, Passos

CJ, Guimarães JR, Barbosa F Jr and Mergler D: Selenium from dietary

sources and motor functions in the Brazilian Amazon.

Neurotoxicology. 32:944–953. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Lemire M, Philibert A, Fillion M, Passos

CJ, Guimarães JR, Barbosa F Jr and Mergler D: No evidence of

selenosis from a selenium-rich diet in the Brazilian Amazon.

Environ Int. 40:128–136. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Qin HB, Zhu JM, Liang L, Wang MS and Su H:

The bioavailability of selenium and risk assessment for human

selenium poisoning in high-Se areas, China. Environ Int. 52:66–74.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Martens IB, Cardoso BR, Hare DJ,

Niedzwiecki MM, Lajolo FM, Martens A and Cozzolino SM: Selenium

status in preschool children receiving a Brazil nut-enriched diet.

Nutrition. 31:1339–1343. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Chawla R, Loomba R, Chaudhary RJ, Singh S

and Dhillon KS: Impact of high selenium exposure on organ function

and biochemical profile of the rural population living in

seleniferous soils in Punjab, IndiaGlobal advance in selenium

research from theory to application. CRC Press; Sao Paulo: pp.

93–94. 2015, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Yu SY, Zhu YJ and Li WG: Protective role

of selenium against hepatitis B virus and primary liver cancer in

Qidong. Biol Trace Elem Res. 56:117–124. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Yu SY, Zhu YJ, Li WG, Huang QS, Huang CZ,

Zhang QN and Hou C: A preliminary report on the intervention trials

of primary liver cancer in high-risk populations with nutritional

supplementation of selenium in China. Biol Trace Elem Res.

29:289–294. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Li WG: Preliminary observations on effect

of selenium yeast on high risk populations with primary liver

cancer. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 26:268–271. 1992.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Li W, Zhu Y, Yan X, Zhang Q, Li X, Ni Z,

Shen Z, Yao H and Zhu J: The prevention of primary liver cancer by

selenium in high risk populations. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi.

34:336–338. 2000.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Lotan Y, Goodman PJ, Youssef RF, Svatek

RS, Shariat SF, Tangen CM, Thompson IM Jr and Klein EA: Evaluation

of vitamin E and selenium supplementation for the prevention of

bladder cancer in SWOG coordinated SELECT. J Urol. 187:2005–2010.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Klein EA, Thompson IM Jr, Tangen CM,

Crowley JJ, Lucia MS, Goodman PJ, Minasian LM, Ford LG, Parnes HL,

Gaziano JM, et al: Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: The

Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA.

306:1549–1556. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Marshall JR, Tangen CM, Sakr WA, Wood DP

Jr, Berry DL, Klein EA, Lippman SM, Parnes HL, Alberts DS, Jarrard

DF, et al: Phase III trial of selenium to prevent prostate cancer

in men with high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia: SWOG

S9917. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 4:1761–1769. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|