Introduction

Tea is one of the most widely consumed beverages

worldwide, the health benefits of which have been recorded against

numerous diseases in ancient China (1). In terms of worldwide distribution,

black tea is mainly consumed in Western countries, whereas green

tea is more common in Asian countries. It has been reported that

tea polyphenols can inhibit osteoclast formation and

differentiation in rats (2);

however, the mechanism underlying the protective effects of tea

polyphenols on cartilage cells have yet to be elucidated.

Theaflavins (TFs) are the primary active polyphenols in black tea,

which include theaflavin-3-gallate, theaflavin-3′-gallate and

theaflavin-3-3′-digallate (3). TFs

have been reported to possess numerous properties including

antioxidant, antiviral and anticancer activities, in various

biological processes (4,5). Cartilage degeneration is associated

with the progression of osteoarthritis, and is mainly induced by

oxidative stress (6). The present

study aimed to explore the potential effect of TFs, in particular

theaflavin-3-3′-digallate, on an in vitro model of cartilage

degeneration and the related mechanisms.

Progressive cartilage destruction can be attributed

to several factors (7). Among

these factors, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are responsible for

the maintenance of cartilage homeostasis; ROS act as the critical

signaling intermediate of intracellular signaling pathways,

including the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B and c-Jun

N-terminal kinase pathways (8,9).

Over-accumulation of ROS may lead to the disruption of cartilage

homeostasis (10,11). In addition, apoptosis is considered

to be associated with cartilage degeneration (12,13).

It has been reported that overproduction of ROS can trigger

intracellular DNA damage, which serves as a cellular stress factor

(8). Furthermore, it has been

demonstrated that Forkhead box (FOX) transcription factors are

implicated in cell cycle progression, immune regulation, tumor

growth and the aging process (14). FOXO proteins are able to regulate

oxidative stress resistance through controlling downstream

antioxidant targets, including glutathione peroxidase 1 (Gpx1) and

catalase (CAT) (15,16). In addition, AKT serine/threonine

kinase (AKT) serves important roles in cell survival and its

activation can phosphorylate several downstream proteins, including

FOXO3a. The transcriptional inactivation of FOXO3a can be induced

by phosphorylation via AKT (17).

Based on these findings, it is likely that AKT/FOXO signaling may

be associated with the protective effect of TFs in cartilage

cells.

The present study aimed to investigate the

protective effect of TFs on cartilage cells and attempted to

explore the underlying mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and grouping

Human chondrocytes (cat. no. 4650; ScienCell

Research Laboratories, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) were cultured in a

6-well plate (1×105/well) at 37°C in a 5% CO2

incubator with Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing 10%

fetal bovine serum (both Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.,

Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Cells were fixed with 95%

ethanol for 15 sec at room temperature and then stained with 1%

toluidine blue (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd., Beijing, China) for 5 min at room temperature and observed

under a light microscope (magnification, ×100).

Theaflavin-3-3′-digallate (purity >90%) was purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). At ~80% confluence,

the cells were serum-starved overnight and were then divided into

three treatment groups for comparison: i) Control group; ii) model

group, in which cells were treated with 0.3 mM

H2O2 for 6 h; and iii) TF pretreatment

groups, in which cells were pretreated with various doses of TFs

(10 and 20 µg/ml) for 12 h, followed by 6 h

H2O2 incubation. The TF concentrations

employed were based on previous literature (18,19).

For the activation of AKT, cells were pretreated with 50 ng/ml

insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I; R&D Systems, Inc.,

Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 10 min prior to

H2O2 or TF treatment, according to previous

studies (20,21).

Cell Counting kit (CCK)-8 assay

The cells were serum starved overnight in a 96-well

plate (1×105 cells/well), and were then treated with

H2O2 (0.1–0.5 µM) in serum-free medium for

various durations (6, 12, 24 and 48 h). A CKK-8 kit was used to

detect cell viability, according to the manufacturer's protocol

(Beijing Kangwei Century Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

Briefly, the CCK-8 solution was added to each well and the cells

were incubated for 4 h at 37°C, after which, absorbance was

measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

ELISA assay

The cells were seeded at a density of

1×104 cells/well in a 96-well plate and were treated as

aforementioned. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 (cat. no. DY511)

and interleukin (IL)-1β (cat. no. DLB50) activities were detected

using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Inc.), according to the

manufacturer's protocols. The ELISA kit used to measure the

expression of cartilage glycoprotein 39 (Cgp-39; cat. no. HC021)

was purchased from Shanghai GeFan Biotechnology, Co., Ltd.

(Shanghai, China).

Flow cytometric analysis of ROS

levels

The cells (1×104 cells/well) were treated

as aforementioned. Subsequently, the cells were stained with

H2DCHF-DA (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for ROS

measurement, as previously described (22). BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences,

Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) running BD CellQuest™ software

version 3.3 (BD Biosciences) was used to perform flow cytometric

analysis. All data are representatives of at least three

independent experiments.

Flow cytometric analysis of

apoptosis

The cells (1×105/well) were cultured in

6-well plates. An Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis kit

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to detect

apoptosis. According to the manufacturer's protocol, Annexin-V and

PI staining was analyzed using analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD

FACSCanto II) with FACSDiva software version 6.1 (both BD

Biosciences).

Flow cytometric analysis of DNA

damage

According to a previous study (23), DNA damage was estimated using flow

cytometry-based detection of γ-H2A histone family, member X

(γ-H2AX). Briefly, the collected cells were suspended in BD

Cytofix/Cytoperm fixation and permeabilization solution (BD

Biosciences). After a 15-min incubation at 37°C, the cells were

washed using PBS and blocked with 10% normal goat serum (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were

incubated with anti-γ-H2AX (pS139) antibody (cat. no. ab26350;

1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at 4°C overnight and then incubated

with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies

(cat. no. ab7064; 1:1,000; Abcam) for 45 min at 37°C. Subsequently,

the fluorescent signals were measured using a BD flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences).

Total RNA isolation and reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using RNAiso reagent (Takara

Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan). Subsequently, cDNA was reverse transcribed

from total RNA using ReverTra Ace (Toyobo Life Science, Osaka,

Japan) and oligo-dT (Takara Bio, Inc.), according to manufacturer's

protocol. The mRNA expression levels were quantified using an ABI

7500 Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) using AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme,

Piscataway, NJ, USA). The thermocycling conditions were as follows:

95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 sec and 60°C

for 30 sec, and final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Relative

expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq

method (24). Primer sequences for

RT-qPCR were as follows: ATR serine/threonine kinase (ATR) forward,

5′-GGAATCACGACTCGCTGA; AC-3′ reverse, 5′-AAATCGGCCCACTAGTAGCA-3′;

ATM serine/threonine kinase (ATM) forward,

5′-CGAGGCGTACAATGGTGAAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCTCCGGCTAAGCGAAATTC-3′;

B-cell lymphoma 2-associated X protein (Bax) forward,

5′-GAGCGGCGGTGATGGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGGATGAAACCCTGAAGCAAA-3′;

and β-actin forward, 5′-CTCTTCCAGCCTTCCTTCC-3′; and reverse,

5′-AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG-3′.

Western blot analysis

A Total Extraction Sample kit (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) was used to extract total proteins. Protein concentration was

determined using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay kit

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The proteins (20 µg/lane) were

separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and were then transferred onto a

polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. To block non-specific proteins,

non-fat milk (3%) was used to incubate the membrane for 2 h at room

temperature. Following incubation with primary antibodies overnight

at 4°C, the membrane was incubated with secondary antibodies for 2

h at room temperature, and the bands were developed using an

enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (GE Healthcare Life Sciences,

Little Chalfont, UK). Blot density was determined using Quantity

One software version 4.6.9 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The

primary antibodies used were as follows: Anti-ATR (cat. no. ab2905;

1:1,000), anti-Bax (cat. no. ab53154; 1:1,000; both Abcam,

Cambridge, UK), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (cat. no. 9664; 1:1,000;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), anti-ATM (cat.

no. ab78; 1:2,000), anti-γH2AX (cat. no. ab11175; 1:8,000; both

Abcam), anti-phosphorylated (p)-AKT (cat. no. 13038; 1:1,000; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-AKT1/2 (cat. no. ab182729;

1:5,000), anti-p-FOXO3a (cat. no. ab53287; 1:1,000; both Abcam),

anti-FOXO3a (cat. no. 2497; 1:1,000; CST), anti-Gpx1 (cat. no.

ab22604; 1:1,000), anti-CAT (cat. no. ab16731; 1:2,000; both Abcam)

and anti-β-actin (cat. no. 4970; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary

antibodies (goat anti-rabbit; cat. no. ab205718; 1:2,000 and goat

anti-mouse; cat. no. ab205719; 1:5,000) were obtained from

Abcam.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were independently performed ≥3

times. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviation.

GraphPad software version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla,

CA, USA) was used to compare differences between groups by one-way

analysis of variance followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

TFs inhibit ROS generation in

cartilage degeneration

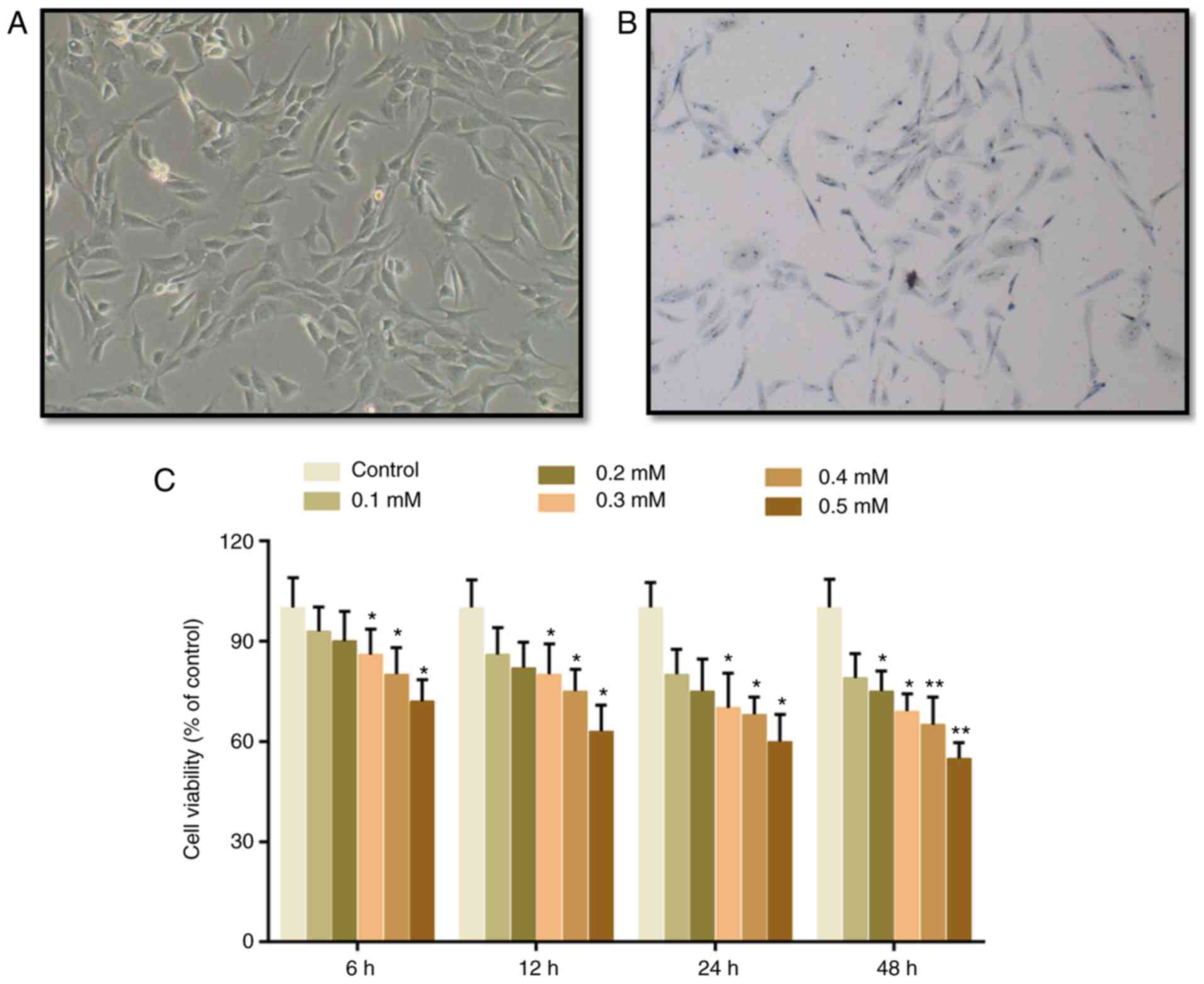

The cartilage cells presented with spindle

morphology, and toluidine blue staining was conducted to identify

the cells. It was identified that the cytoplasm was stained light

blue and the nucleus was stained dark blue, indicating that these

cells were chondrocytes (Fig. 1A and

B). Subsequently, CCK-8 assay was conducted to evaluate the

effects of H2O2 on the viability of cartilage

cells. It was demonstrated that cell viability was suppressed by

H2O2 in a dose-dependent manner. A

significant difference emerged in the group that was treated with

0.3 mM H2O2 for 6 h, in which cell viability

was deceased by 14% (Fig. 1B).

Therefore, 0.3 mM H2O2 was subsequently used

to treat cartilage cells for 6 h, in order to mimic the progression

of cartilage degeneration. To measure cartilage degeneration

following H2O2 treatment, the expression

levels of catabolic factors, MMP-13, IL-1β and Cgp-39, were

detected. It was demonstrated that the expression levels of MMP-13,

IL-1β and Cgp-39 were increased by H2O2, but

were decreased by TF pretreatment (Fig. 2A). These findings suggested that

TFs may inhibit cartilage degeneration. Furthermore, according to

flow cytometric analysis, it was demonstrated that ROS levels were

markedly decreased in the TF pretreatment groups (Fig. 2B and C).

| Figure 2.(A) Detection of catabolic factors,

MMP-13, IL-1β and Cgp-39. (B) ROS production rate was determined

following treatment with TFs and H2O2. (C)

ROS levels were measured by flow cytometry. **P<0.01 vs.

control; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs. MG;

^P<0.05, ^^P<0.01 vs. T1 +

H2O2. Cgp, cartilage glycoprotein; IL,

interleukin; MG, model group; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; ROS,

reactive oxygen species; T1, pretreatment with 10 µg/ml TFs; T2,

pretreatment with 20 µg/ml TFs; TFs, theaflavins. |

TFs suppress apoptosis and DNA damage

following oxidative stress

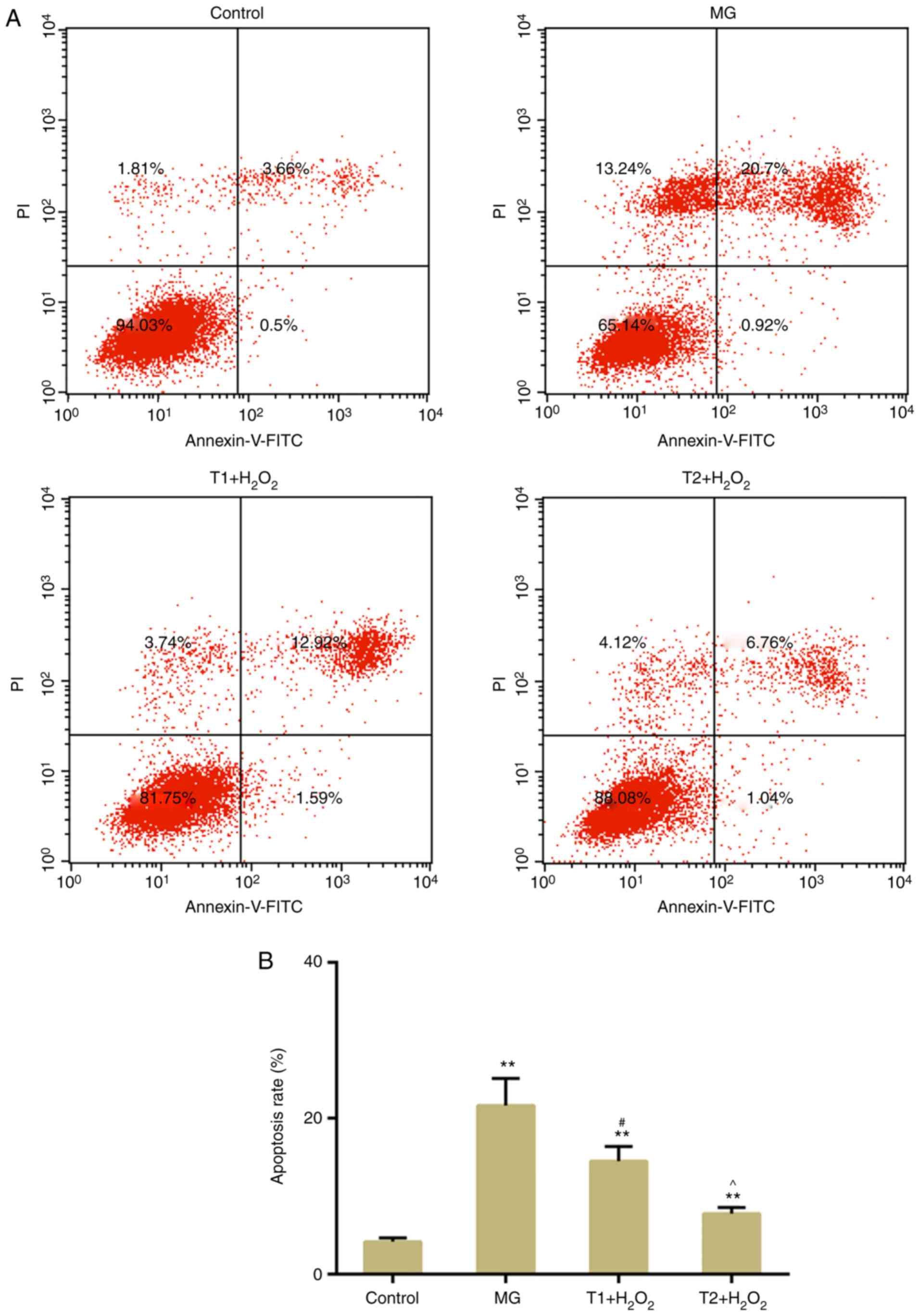

The results of flow cytometric analysis revealed

that H2O2-induced apoptosis was suppressed by

pretreatment with TFs (Fig. 3A and

B). DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are a type of detrimental

DNA damage, for which γH2AX is considered a surrogate marker. In

response to DSBs, H2AX is phosphorylated at Ser139 (γH2AX)

(25). The present results

demonstrated that TFs could decrease γH2AX expression compared with

in the model group (Fig. 4A and

B). In addition, western blotting confirmed that TFs inhibited

the expression levels of γH2AX (Fig.

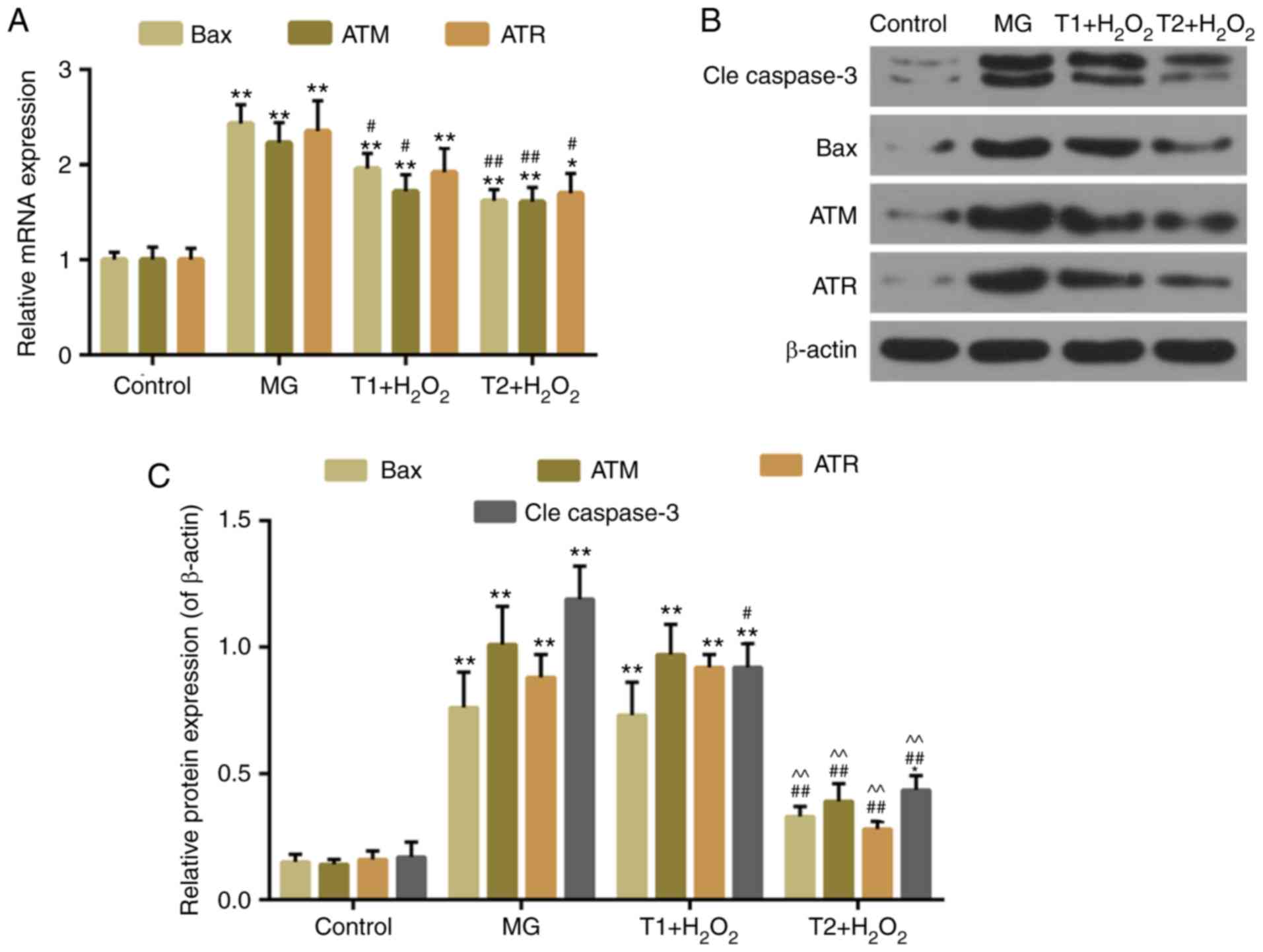

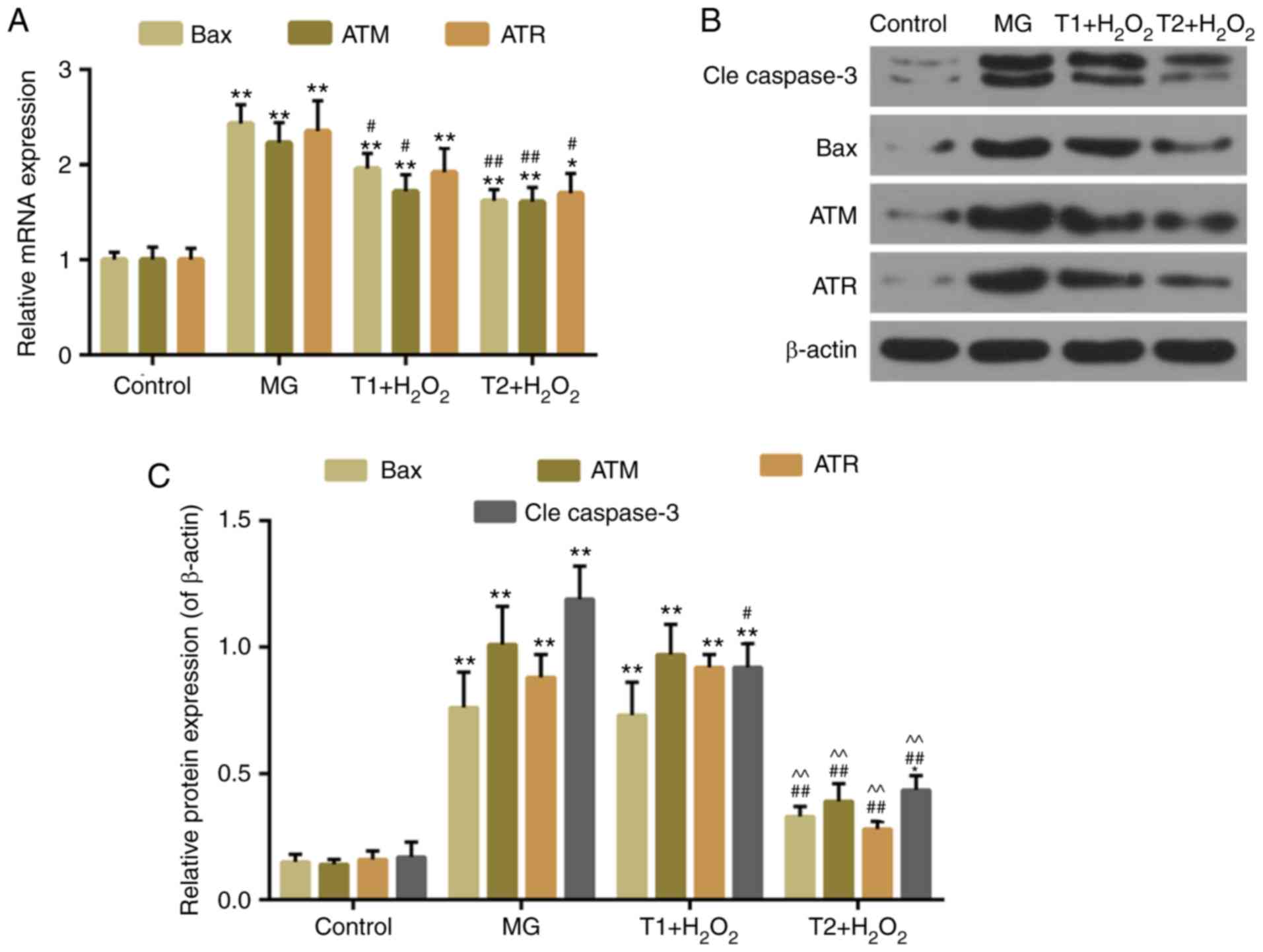

4C). The expression levels of apoptosis-associated factors,

including cleaved caspase-3 and Bax, were decreased in the TF

pretreatment groups compared with in the model group. The

expression levels of DNA damage-response genes, ATM and ATR, were

also decreased following TF pretreatment (Fig. 5A-C). However, the protein

expression levels of ATR were slightly, but not significantly,

increased in the T1 + H2O2 group.

| Figure 5.(A) Quantitative analysis of Bax, ATR

and ATM mRNA expression. (B and C) Western blot analysis of cleaved

caspase-3, Bax, ATR and ATM. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs.

control; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs. MG;

^^P<0.01 vs. T1 + H2O2. ATM,

ATM serine/threonine kinase; ATR, ATR serine/threonine kinase; Bax,

B-cell lymphoma 2-associated X protein; MG, model group; T1,

pretreatment with 10 µg/ml TFs; T2, pre-treatment with 20 µg/ml

TFs; TFs, theaflavins. |

TFs decrease the activity of AKT,

FOXO3a, Gpx1 and CAT

Emerging evidences have demonstrated that FOXO

proteins are important mediators of oxidative stress (15,16).

Compared with in the model group, the protein expression levels of

p-AKT and p-FOXO3a were mitigated by TF pretreatment, whereas the

expression levels of Gpx1 and CAT were enhanced (Fig. 6A and B).

| Figure 6.(A and B) Western blot analysis of

AKT, p-AKT, FOXO3a, p-FOXO3a, Gpx1 and CAT. **P<0.01 vs.

control; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs. MG;

^^P<0.01 vs. T1 + H2O2. CAT,

catalase; FOXO3a, Forkhead box O3a; MG, model group; Gpx,

glutathione peroxidase 1; p-, phosphorylated; T1, pretreatment with

10 µg/ml TFs; T2, pre-treatment with 20 µg/ml TFs; TFs,

theaflavins. |

AKT activity is necessary for the

protective effects of TFs

To further confirm the role of AKT in the present

study, apoptosis and DNA damage were detected following treatment

with the AKT activator, IGF-I. The results demonstrated that TF

pretreatment did not significantly reverse

H2O2-induced apoptosis following persistent

activation of AKT (Fig. 7A and B).

In addition, TF-induced inhibition of DNA damage was reversed

following persistent activation of AKT (Fig. 8A-C).

Discussion

Tea is one of the most widely consumed beverages

worldwide (26). The potential

health benefits of tea have been widely reported, particularly with

regards to the prevention of cardiovascular disorders and cancer.

Phenols and polyphenols are the primary bioactive substances in tea

that exert health effects (27);

therefore, attention has been paid to the antioxidative effects of

tea polyphenols (28). Cartilage

degeneration is a serious complication of osteoarthritis, which is

mainly caused by oxidative stress (29). A previous study demonstrated the

positive function of tea polyphenols in maintaining bone

homeostasis (2). TFs are the

primary active content of tea phenols (30); however, little is currently known

about the effects of TFs on cartilage degeneration.

Studies have revealed the connection between

structural degeneration and biochemical markers (31–34).

Several biochemical markers, including MMP-13 (32), IL-1β (33) and Cgp-39 (34), are used to diagnose patients with a

high risk of joint degeneration. The present study demonstrated

that TFs inhibited H2O2-mediated cartilage

degeneration by decreasing the levels of MMP-13, IL-1β and Cgp-39.

This study also aimed to illustrate the molecular mechanisms

underlying the effects of TFs on the cartilage cells. The results

demonstrated that ROS production was markedly increased in the

model group, whereas pretreatment with TFs significantly decreased

ROS levels. Furthermore, pretreatment with TFs reduced cell

apoptosis and DNA damage caused by H2O2, and

decreased the expression levels of cleaved caspase-3 and Bax, which

are closely associated with cell apoptosis (35,36).

The expression levels of ATR and ATM, which is the master kinase

that controls the DNA damage check point (37,38),

were decreased in the TF pretreatment groups compared with in the

model group. These findings indicated that TFs may prevent

cartilage matrix degeneration by inhibiting DNA damage and

apoptosis. The inhibitory effects of TFs on apoptosis were

supported by a recent study in PC12 neural cells (39). In addition, DNA damage can be

modified by TFs in human lymphocytes (40). However, numerous studies have

demonstrated that TFs inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in

cancer cells (41–43). These contradictory results may be

due to the distinct cell types used in each study model.

To explore the possible underlying mechanisms, the

effects of TFs on the activity of AKT/FOXO3 signaling were

investigated. It was noted that TFs mitigated the expression of

p-AKT and p-FOXO3a, and enhanced Gpx1 and CAT activities compared

with in the model group. It has previously been demonstrated that

the reduced activity of AKT/FOXOs mitigates cell dysfunction in

diabetic kidney disease (44).

Notably, the present study revealed that TF-induced inhibition of

apoptosis and DNA damage was reversed following persistent

activation of AKT. Therefore, it may be hypothesized that the

effects of TFs on cartilage cells may be tightly linked to AKT/FOXO

signaling. Since phosphorylation of FOXO3 results in its

inactivation, TFs may reduce inactivation of FOXO3 by suppressing

AKT. However, this speculation was not validated in the present

study. The protective effect of FOXO3 inactivation on cartilage

still requires further investigation. In addition, the activity of

FOXOs can be regulated by other signals (45); however, the regulation is rather

complex, and parts of it are contradictory. For example, FOXO3 can

be activated by the phosphorylation of 5′AMP-activated protein

kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinase and macrophage-stimulating 1

(46). Therefore, it would be

useful to investigate how the upstream signals co-regulate FOXO3

signaling in future studies.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

TFs inhibited the ROS burst in cartilage destruction. TFs

suppressed apoptosis and DNA damage by reducing the expression

levels of cleaved caspase-3, Bax, ATR and ATM. Furthermore, TFs

enhanced the activity of Gpx1 and CAT, and decreased the expression

levels of p-AKT and p-FOXO3a. Notably, AKT signaling was necessary

for the effects of TFs on apoptosis and DNA damage. The results of

the present study demonstrated that TFs may be a potential

candidate drug for the prevention of cartilage degeneration.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

JL and JZ designed the study, performed the

experiments and performed the data analysis. JL wrote the

manuscript. JL and JZ revised the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Graham HN: Tea: The plant and its

manufacture; chemistry and consumption of the beverage. Prog Clin

Biol Res. 158:29–74. 1984.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Oka Y, Iwai S, Amano H, Irie Y, Yatomi K,

Ryu K, Yamada S, Inagaki K and Oguchi K: Tea polyphenols inhibit

rat osteoclast formation and differentiation. J Pharm Sci.

118:55–64. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Liu S, Lu H, Zhao Q, He Y, Niu J, Debnath

AK, Wu S and Jiang S: Theaflavin derivatives in black tea and

catechin derivatives in green tea inhibit HIV-1 entry by targeting

gp41. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1723:270–281. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Maron DJ, Lu GP, Cai NS, Wu ZG, Li YH,

Chen H, Zhu JQ, Jin XJ, Wouters BC and Zhao J: Cholesterol-lowering

effect of a theaflavin-enriched green tea extract: A randomized

controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 163:1448–1453. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lin JK, Chen PC, Ho CT and Lin-Shiau SY:

Inhibition of xanthine oxidase and suppression of intracellular

reactive oxygen species in HL-60 cells by

theaflavin-3,3′-digallate, (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, and

propyl gallate. J Agric Food Chem. 48:2736–2743. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Pap T and Korb-Pap A: Cartilage damage in

osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis-two unequal siblings. Nat

Rev Rheumatol. 11:606–615. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hosseinzadeh A, Kamrava SK, Joghataei MT,

Darabi R, Shakeri-Zadeh A, Shahriari M, Reiter RJ, Ghaznavi H and

Mehrzadi S: Apoptosis signaling pathways in osteoarthritis and

possible protective role of melatonin. J Pineal Res. 61:411–425.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lepetsos P and Papavassiliou AG:

ROS/oxidative stress signaling in osteoarthritis. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1862:576–591. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yu SM and Kim SJ: Withaferin A-caused

production of intracellular reactive oxygen species modulates

apoptosis via PI3K/Akt and JNKinase in rabbit articular

chondrocytes. J Korean Med Sci. 29:1042–1053. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Chen AF, Davies CM, De Lin M and Fermor B:

Oxidative DNA damage in osteoarthritic porcine articular cartilage.

J Cell Physiol. 217:828–833. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Davies CM, Guilak F, Weinberg JB and

Fermor B: Reactive nitrogen and oxygen species in

interleukin-1-mediated DNA damage associated with osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 16:624–630. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hashimoto S, Ochs RL, Komiya S and Lotz M:

Linkage of chondrocyte apoptosis and cartilage degradation in human

osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 41:1632–1638. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kim HA and Blanco FJ: Cell death and

apoptosis in osteoarthritic cartilage. Curr Drug Targets.

8:333–345. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Calnan DR and Brunet A: The FoxO code.

Oncogene. 27:2276–2288. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

van der Horst A and Burgering BMT:

Stressing the role of FoxO proteins in lifespan and disease. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 8:440–450. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Brigelius-Flohé R and Maiorino M:

Glutathione peroxidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1830:3289–3303.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

García Z, Kumar A, Marqués M, Cortés I and

Carrera AC: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase controls early and late

events in mammalian cell division. EMBO J. 25:655–661. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang W, Sun Y, Liu J, Wang J, Li Y, Li H

and Zhang W: Protective effect of theaflavins on

homocysteine-induced injury in HUVEC cells in vitro. J Cardiovasc

Pharmacol. 59:434–440. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lahiry L, Saha B, Chakraborty J,

Bhattacharyya S, Chattopadhyay S, Banerjee S, Choudhuri T, Mandal

D, Bhattacharyya A, Sa G and Das T: Contribution of p53-mediated

Bax transactivation in theaflavin-induced mammary epithelial

carcinoma cell apoptosis. Apoptosis. 13:771–781. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wu CJ, O'Rourke DM, Feng GS, Johnson GR,

Wang Q and Greene MI: The tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 is required

for mediating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt activation by

growth factors. Oncogene. 20:6018–6025. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yamada T, Takeuchi S, Fujita N, Nakamura

A, Wang W, Li Q, Oda M, Mitsudomi T, Yatabe Y, Sekido Y, et al: Akt

kinase-interacting protein1, a novel therapeutic target for lung

cancer with EGFR-activating and gatekeeper mutations. Oncogene.

32:4427–4435. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Fani S, Kamalidehghan B, Lo KM, Nigjeh SE,

Keong YS, Dehghan F, Soori R, Abdulla MA, Chow KM, Ali HM, et al:

Anticancer activity of a monobenzyltin complex C1 against

MDA-MB-231 cells through induction of Apoptosis and inhibition of

breast cancer stem cells. Sci Rep. 6:389922016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Li J, Guo YY, Wu W, Bai JL, Xuan ZQ, Yang

J and Wang J: Detecting DNA damage of human lymphocytes exposed to

1,2-DCE with γH2AX identified antibody using flow cytometer assay.

Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 29:16–19. 2011.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yu YK, Lu Y, Yu Y and Yang J: γH2AX: A

biomarker for DNA double-stranded breaks. Chin J Pharm Tox.

19:237–240. 2005.

|

|

26

|

Wang D, Gao Q, Wang T, Qian F and Wang Y:

Theanine: the unique amino acid in the tea plant as an oral

hepatoprotective agent. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 26:384–391.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Schneider C and Segre T: Green tea:

Potential health benefits. Am Fam Physician. 79:591–594.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tipoe GL, Leung TM, Hung MW and Fung ML:

Green tea polyphenols as an anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory

agent for cardiovascular protection. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug

Targets. 7:135–144. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li YS, Xiao WF and Luo W: Cellular aging

towards osteoarthritis. Mech Ageing Dev. 162:80–84. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Morinobu A, Biao W, Tanaka S, Horiuchi M,

Jun L, Tsuji G, Sakai Y, Kurosaka M and Kumagai S:

(−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate suppresses osteoclast

differentiation and ameliorates experimental arthritis in mice.

Arthritis Rheum. 58:2012–2018. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Bruyere O, Collette JH, Ethgen O, Rovati

LC, Giacovelli G, Henrotin YE, Seidel L and Reginster JY:

Biochemical markers of bone and cartilage remodeling in prediction

of longterm progression of knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol.

30:1043–1050. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Attur M, Yang Q, Kirsch T and Abramson SB:

Role of periostin and discoidin domain receptor-1 (DDR1) in the

regulation of cartilage degeneration and expression of MMP-13.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 24:S1562016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Goldring SR: Pathogenesis of bone and

cartilage destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology

(Oxford). 42 Suppl 2:ii11–ii16. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zivanović S, Rackov LP, Vojvodić D and

Vucetić D: Human cartilage glycoprotein 39-biomarker of joint

damage in knee osteoarthritis. Int Orthop. 33:1165–1170. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Oltvai ZN, Milliman CL and Korsmeyer SJ:

Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that

accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 74:609–619. 1993.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Porter AG and Jänicke RU: Emerging roles

of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 6:99–104. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lee JH and Paull TT: Activation and

regulation of ATM kinase activity in response to DNA double-strand

breaks. Oncogene. 26:7741–7748. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kaçmaz K

and Linn S: Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the

DNA damage checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem. 73:39–85. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhang J, Cai S, Li J, Xiong L, Tian L, Liu

J, Huang J and Liu Z: Neuroprotective effects of theaflavins

against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Neurochem

Res. 41:3364–3372. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Alotaibi A, Bhatnagar P, Najafzadeh M,

Gupta KC and Anderson D: Tea phenols in bulk and nanoparticle form

modify DNA damage in human lymphocytes from colon cancer patients

and healthy individuals treated in vitro with platinum-based

chemotherapeutic drugs. Nanomedicine (Lond). 8:389–401. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Adhikary A, Mohanty S, Lahiry L, Hossain

DM, Chakraborty S and Das T: Theaflavins retard human breast cancer

cell migration by inhibiting NF-kappaB via p53-ROS cross-talk. FEBS

Lett. 584:7–14. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Bhattacharya U, Halder B, Mukhopadhyay S

and Giri AK: Role of oxidation-triggered activation of JNK and p38

MAPK in black tea polyphenols induced apoptotic death of A375

cells. Cancer Sci. 100:1971–1978. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Schuck AG, Ausubel MB, Zuckerbraun HL and

Babich H: Theaflavin-3,3′-digallate, a component of black tea: An

inducer of oxidative stress and apoptosis. Toxicol In Vitro.

22:598–609. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Kato M, Yuan H, Xu ZG, Lanting L, Li SL,

Wang M, Hu MC, Reddy MA and Natarajan R: Role of the Akt/FoxO3a

pathway in TGF-beta1-mediated mesangial cell dysfunction: A novel

mechanism related to diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soci Nephrol.

17:3325–3335. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Zhao Y, Wang Y and Zhu WG: Applications of

post-translational modifications of FoxO family proteins in

biological functions. J Mol Cell Biol. 3:276–282. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wilk A, Urbanska K, Yang S, Wang JY, Amini

S, Del Valle L, Peruzzi F, Meggs L and Reiss K: Insulin-like growth

factor-I-forkhead box O transcription factor 3a counteracts high

glucose/tumor necrosis factor-α-mediated neuronal damage:

Implications for human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J

Neurosci Res. 89:183–198. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|