Introduction

Human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs) possess the

ability to proliferate and to differentiate into odontoblasts,

which enables them to participate in the reconstruction and repair

of diseased pulp tissue (1–3). At

present, dental caries, and the subsequent inflammation caused by

dental pathogens, are common and nonnegligible clinical problems

(4,5). Human carious dental pulp stem cells

(hCDPSCs) have attracted increasing levels of attention (6). Compared with normal hDPSCs, hCDPSCs

have a number of advantages, such as a high proliferation rate and

easy availability (6–9). hCDPSCs are considered to be ideal

‘seed’ cells in tissue engineering, although their characteristics

have yet to be fully elucidated.

Growth factors (GFs) are types of polypeptide or

glycoprotein that possess the biological properties of promoting

cell proliferation, differentiation and locomotion (10–12).

Among them, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and

insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) are two important GFs with

unique functions (13–15). VEGF has the capacity to trigger

newly forming vessels in order to provide a blood supply for bone

regeneration (16). IGF-1, a

member of the insulin-like peptide family, is a ubiquitous and

important peptide hormone and anti-apoptotic factor that exerts

important roles in organ apoptosis and differentiation (17). It has been reported that IGF-1 may

promote the proliferation of dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) and

periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), and induce their

osteogenic/odontogenic differentiation (18,19).

It has been shown, that when either VEGF (25 ng/ml) or IGF-1 (100

ng/ml) was used, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) exhibited the

strongest proliferative capacity (19–21).

Furthermore, it was reported that the combined use of VEGF and

IGF-1 enhanced osteogenic differentiation of periosteum-derived

progenitor cells (PDPCs) and skin-derived MSCs (S-MSCs) (22). However, to the best of our

knowledge, the effects of VEGF and IGF-1, either alone or in

combination, on hCDPSCs has yet to be elucidated.

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling

pathway is an important signal transduction pathway, which tightly

controls cell proliferation, migration, differentiation and

self-renewal (23,24). It has been reported that activation

of the AKT signaling pathway led to an improvement in the

proliferative and differentiation abilities of MSCs, thereby

enhancing stemness (25).

In the present study, IGF-1 and VEGF, when applied

either alone or in combination, were observed to exert an effect on

the proliferation, migration and differentiation of hCDPSCs in

vitro, and these effects were found to be associated with the

AKT signaling pathway. These findings add to our knowledge of the

cellular biological foundation for clinical application of hCDPSCs

in the treatment of dental pulp disease.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture of hCDPSCs

hCDPSCs were obtained from the carious pulp tissues,

which were collected from teeth diagnosed with deep caries. The

diagnosis of deep caries was determined by endodontic specialists

on the basis of clinical assessment (26). A total of 20 patients (28–30 years

of age; 10 male and 10 female patients) were informed about the

nature of this research project, agreed to participate, and signed

informed consent forms for scientific experiments involving tooth

extraction in the Department of Stomatology of Nanfang Hospital,

Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, China). The study protocol

was performed according to a standard protocol approved by the

Ethics Committee of the Southern Medical University. The pulp was

carefully collected (1/3 of the apical pulp was discarded), cut

into small pieces, and digested with collagenase (3 mg/ml)/dispase

enzyme (4 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 30 min. After 7–10

days, the primary cultured hCDPSCs were observed to be able to

climb out along the edge of the tissue blocks. When the confluence

of hCDPSCs reached ~80%, the cells were subcultured in new flasks.

Cells were cultured with HyClone™ α-Minimal Essential Medium

(α-MEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% Gibco fetal

bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (all

from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For all incubations in

the methods section, unless specified otherwise, cells were

cultured at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Phenotypic identification of

hCDPSCs

Passage 3 hCDPSCs in the exponential growth phase

were collected by 0.25% Trypsin and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 1

min at 37°C, and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to

prepare a single cell suspension with a density of

1×106/ml. The hCDPSCs were incubated with antihuman

CD29PE (1:300, cat. no. 557332;), CD44PE (1:300, cat. no. 562818),

CD45-PC5 (1:300, cat. no. 555484), CD90-PC5 (1:300, cat. no.

561972), CD105-PE (1:300, cat. no. 560839) and CD133-APC (1:300,

cat. no. 566596; all from BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA)

antibodies in different tubes at room temperature for 30 min,

before washing three times with PBS and resuspending the cells in

300 µl PBS. Fc blocking reagent was used to block the non-specific

detection of the Fc component of all antibodies. Flow cytometry (BD

Accuri C6, Becton Dickinson Biosciences) was used to detect the

positive rate of stem cell surface markers. All data were analyzed

by FlowJo Software (v10.0; FlowJo LLC).

Cell monoclonal assay and osteogenic

induction

hCDPSCs (2,000 cells) were inoculated into a 10 cm

culture dish at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After

14 days, hCDPSCs were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 mins and

stained with Giemsa for 10 mins in 37°C Clones with >50 cells

were counted as one unit.

Passage 3 hCDPSCs were cultured with osteogenic

medium (10% FBS, 10 mmol/l sodium β-glycerophosphate, 50 mg/l

ascorbic acid and 0.1 µmol/l dexamethasone in α-MEM). After 7 days

of induction, hCDPSCs were fixed for 15 min with 4%

paraformaldehyde, and subsequently incubated with ALP stain for 10

min at room temperature. After 21 days of induction, hCDPSCs were

stained with Alizarin red for 10 min at room temperature following

fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. After a thorough rinse, the

cells were observed and counted under a microscope a light

microscope with ×100 magnification.

Effect of VEGF and IGF-1 on

proliferation and migration of hCDPSCs

Passage 3 hCDPSCs in the exponential growth phase

were collected by 0.25% Trypsin and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 1

min at 37°C, and inoculated (1,500 cells) into 96-well plates, and

induced by the addition of no agent (blank control), IGF-1 (100

ng/ml), VEGF (25 ng/ml), or VEGF (25 ng/ml) + IGF-1 (100 ng/ml),

respectively. Cell proliferation was analyzed using a Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

According to the manufacturer's protocol, on days 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9,

the absorbance at 490 nm wavelength was measured following

incubation with CCK8 reagent for 3 h. Similarly, after the cells

were cultured in the different experimental group set-ups,

migration assay was performed in a Transwell chamber. Serum-free

medium was added in the upper chamber, and 5×104 cells

were inoculated in each well. 10% FBS medium was added into the

lower chamber. The cells were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of

5% CO2 for 24 h. Subsequently, the supernatant was

discarded, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min

and stained by 0.1% crystal violet in 37°C.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells in the different

groups using TRIzol®, and total RNA was

reverse-transcribed into cDNA according to the instructions of the

RT kit employed (Qiagen GmbH). The content of RNA was quantified

(Nanodrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). SYBR Green was

purchased from Qiagen GmbH and the sequences of the RT-PCR primers

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) are given in Table I. GAPDH was used as reference gene.

The following thermocycling conditions were used: 95°C for 20 sec,

annealing at 60°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 30 sec (40

cycles). Each assay was performed in triplicate, and quantification

was performed using the 2−ΔΔCq method (27).

| Table I.Primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Sequence |

|---|

| RUNX2 | F:

5′TGGTTACTGTCATGGCGGGTA3′ |

|

| R:

5′TCTCAGATCGTTGAACCTTGCTA3′ |

| BSP | F:

5′CACTGGAGCCAATGCAGAAGA3′ |

|

| R:

5′TGGTGGGGTTGTAGGTTCAAA3′ |

| ALP | F:

5′GAGATGTTGTCCTGACACTTGTG3′ |

|

| R:

5′AGGCTTCCTCCTTGTTGGGT3′ |

| VEGF | F:

5′AGGGCAGAATCATCACGAAGT3′ |

|

| R:

5′AGGGTCTCGATTGGATGGCA3′ |

| PDGF | F:

5′TGGCAGTACCCCATGTCTGAA3′ |

|

| R:

5′CCAAGACCGTCACAAAAAGGC3′ |

| GAPDH | F:

5′ACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGG3′ |

|

| R:

5′GCCATCACGCCACAGTTTC3′ |

Western blot analysis

Passage 3 hCDPSCs from the different groups were

collected by 0.25% Trypsin and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 1 min

at 37°C and washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and subsequently the

total protein was extracted using RIPA buffer (Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology) (28). Aliquots

of 40 µg protein from each sample were subjected to SDSPAGE (10%

gels), and the proteins were subsequently transferred on to PVDF

membranes (Life Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The membranes were

subsequently blocked with TBST containing 5% defatted milk powder

at room temperature for 1 h, and then incubated overnight with

primary antibodies against RUNX2 (1:500, cat. no. 12556), BSP

(1:500, cat. no. 5468S), ALP (1:500, cat. no. 8681), VEGF (1:500,

cat. no. 2463), PDGF (1:500, cat. no. 3169), AKT (1:500, cat. no.

4685), phosphorylated (p)-AKT (1:500, cat. no. 9614) and cyclin D1

(1:500, cat. no. 2978; all antibodies from Cell Signaling

Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight. The membranes were

subsequently washed with PBS three times. Peroxidase-conjugated

goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse was used as the secondary

antibody (cat. no. 4414 or 4410S, respectively; 1:1,000 dilution;

Cell Signaling Technology), and the membranes were incubated with

secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, prior to subsequent

exposure to an Odyssey 2-colour infrared laser imaging system

(LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). The semi-quantitative

results for each western blot were measured using the Image-Pro

Plus 6.0 program (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA).

In vitro Matrigel™ tube formation

assay

Passage 3 hCDPSCs in the exponential growth phase

were collected by 0.25% Trypsin and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 1

min at 37°C, and cell suspensions (1×106 cells) were

prepared. Matrigel™ was coated onto 12-well plates according to the

manufacturer's protocol (29,30).

The cells were gently mixed, inoculated on to the aggregated

Matrigel™, and subsequently were incubated in 37°C in an atmosphere

of 5% CO2 for 7 h. The condition of the vessels was

observed under a light microscope, and the density of vessels was

determined using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 program (Media Cybernetics,

Inc.).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 17.0 was used for statistical analysis. Data

are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons among

groups was performed using one-way ANOVA, and post-hoc comparisons

were performed by the least significant difference (LSD) t test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Identification of hCDPSCs

Passage 3 hCDPSCs were collected and cultured for

stem cell identification. The cells exhibited the property of

monoclonal formation, as well as osteogenic differentiation and

mineralization (Fig. 1A-C). The

flow cytometry experiments revealed positive expression of CD29,

CD44, CD90 and CD105, and negative expression of CD45 and CD133

(Fig. 1D). According to the

criteria for defining multipotent MSCs, the isolated human carious

dental pulp cells were identified as MSCs.

Effects of VEGF and IGF-1 on

proliferation and migration of hCDPSCs

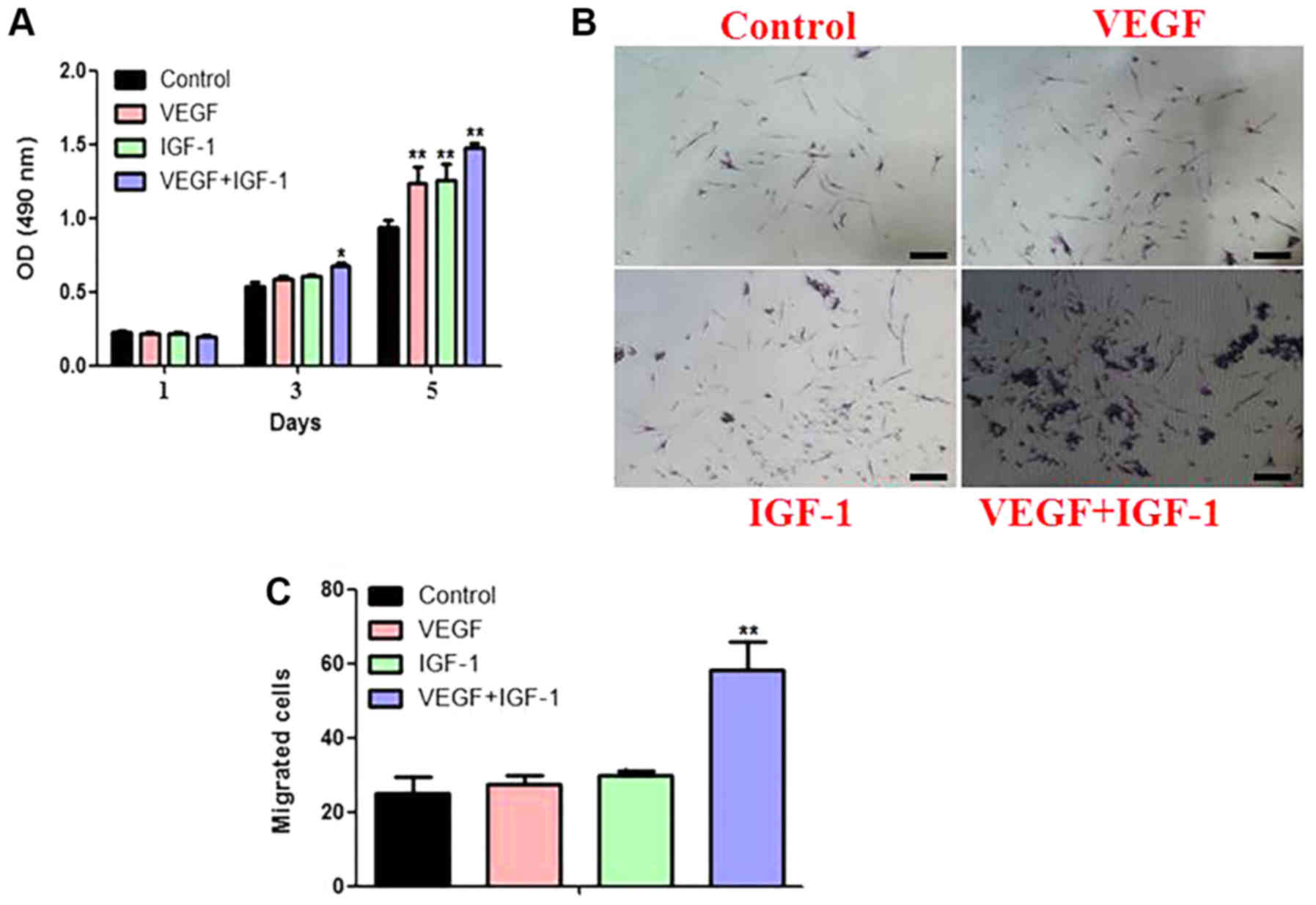

CCK8 assay revealed that the proliferation of

hCDPSCs could be stimulated by adding either VEGF or IGF-1 alone,

whereas the addition of VEGF and IGF-1 in combination led to a

further enhancement in the proliferation rate of the hCDPSCs

(Fig. 2A).

Transwell assay was subsequently used to detect the

migratory ability of hCDPSCs upon treatment with VEGF and IGF-1,

either separately or in combination. The results demonstrated that

there was a synergistic effect of VEGF/IGF-1 treatment on cell

migration, and the effect of combined treatment was greater than

that of either of these two GFs when added in isolation (Fig. 2B).

Effects of VEGF and IGF-1 on

osteogenic differentiation of hCDPSCs in vitro

For these experiments, five experimental groups were

established: Blank control (Con), ordinary osteogenic medium (OM),

osteogenic medium plus VEGF (VEGF + OM), osteogenic medium plus

IGF-1 (IGF-1 + OM), and osteogenic medium plus VEGF and IGF-1 (VEGF

+ IGF-1 + OM). Alizarin red staining and ALP staining revealed

that, compared with the OM group, the osteogenic ability of the

VEGF + IGF-1 + OM group revealed a significant enhancement in the

staining intensity (Fig. 3A-C).

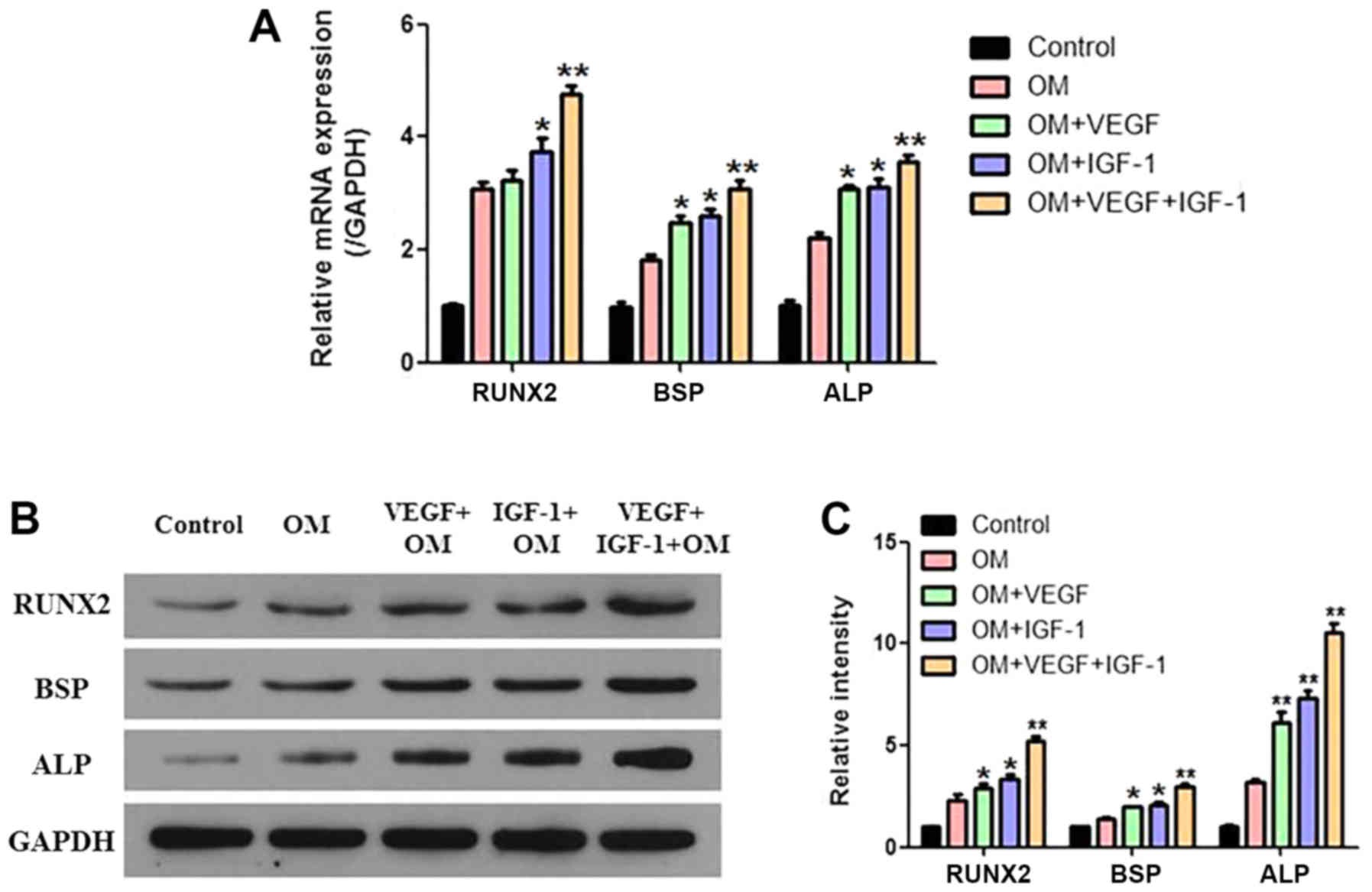

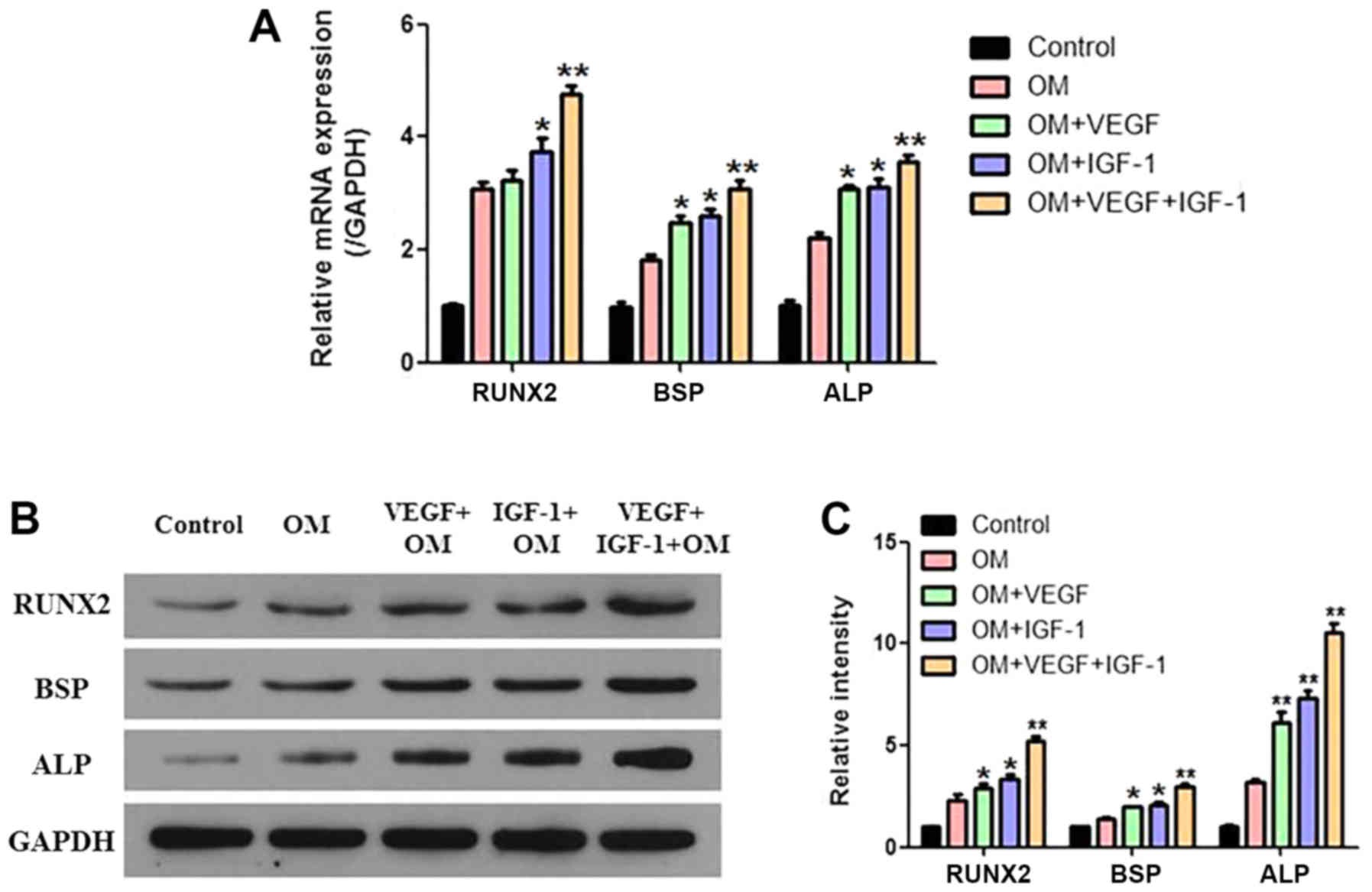

The corresponding RT-qPCR and western blotting results revealed

that the mRNA and protein expression levels of the

osteogenesisassociated genes (i.e., Runx2, BSP and ALP) increased

significantly in the VEGF + OM and IGF-1 + OM groups, whereas the

largest increase was observed for the VEGF + IGF-1 + OM group

(Fig. 4A-C).

| Figure 3.Osteogenic differentiation of hCDPSCs

upon treatment with VEGF and IGF-1. (A) The osteogenic

differentiation capability of hCDPSCs was examined using Alizarin

red staining, with (B) subsequent quantification of the results.

**P<0.01 vs. control. (C) The results from ALP staining are

shown. For the description of the experimental groups (Control, OM,

VEGF+OM, IGF-1+OM and VEGF+IGF-1+OM), see the Results section.

Scale bar, 200 µm. hCDPSCs, human carious dental pulp stem cells;

IGF-1, insulinlike growth factor 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial

growth factor; ALP, alkaline phosphatase. |

| Figure 4.Analysis of the

osteogenesis-associated genes and proteins of hCDPSCs upon

treatment with VEGF and IGF-1. (A) The mRNA expression levels of

the RUNX2, BSP and ALP genes were examined by RT-qPCR. (B) The

protein expression levels of RUNX2, BSP and ALP were examined by

western blotting, and (C) the relative protein expression levels

were normalized against GAPDH. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control.

For the description of the experimental groups (Control, OM,

VEGF+OM, IGF-1+OM and VEGF+IGF-1+OM), see the Results section.

hCDPSCs, human carious dental pulp stem cells; IGF-1, insulin-like

growth factor 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; RUNX2,

Runt-related transcription factor 2; BSP, bone sialoprotein; ALP,

alkaline phosphatase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase. |

Effects of VEGF and IGF-1 on

angiogenic differentiation of hCDPSCs in vitro

Tube formation assays revealed that the number of

tubules could be increased by adding either VEGF or IGF-1 alone,

whereas the addition of VEGF and IGF in combination led to a

further increase in the angiogenic ability of hCDPSCs (Fig. 5B and C). The RT-qPCR and western

blotting results exhibited a similar trend to that of the

osteogenesis-induction assay: The expression of vessel

formation-associated genes and proteins (i.e., VEGF and PDGF)

increased significantly in the OM + VEGF and OM +I GF-1 groups,

whereas the VEGF + IGF-1 + OM group exhibited the greatest

enhancement (Fig. 5A, D and

E).

| Figure 5.Angiogenic differentiation of hCDPSCs

upon treatment with VEGF and IGF-1. (A) mRNA expression levels of

VEGF and PDGF were examined by RT-qPCR. (B and C) Tube-formation

ability was examined in the different groups. Magnification, ×200.

(D) The protein expression levels of VEGF and PDGF were detected by

western blotting, and (E) the relative protein expression level was

normalized against GAPDH. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control. For

the description of the experimental groups (Control, VEGF, IGF-1

and VEGF+IGF-1), see the Results section. hCDPSCs, human carious

dental pulp stem cells; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; VEGF,

vascular endothelial growth factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth

factor; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. |

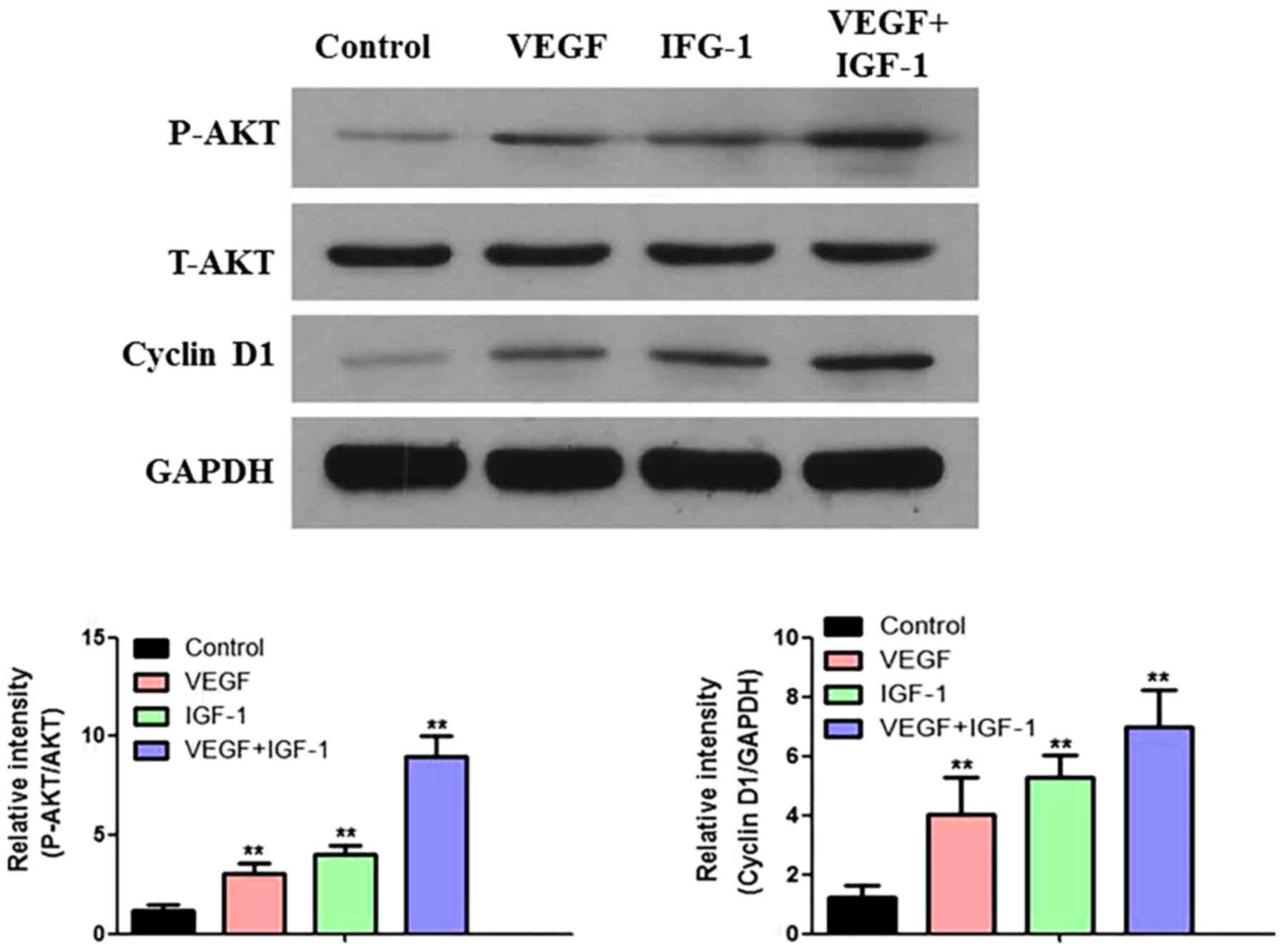

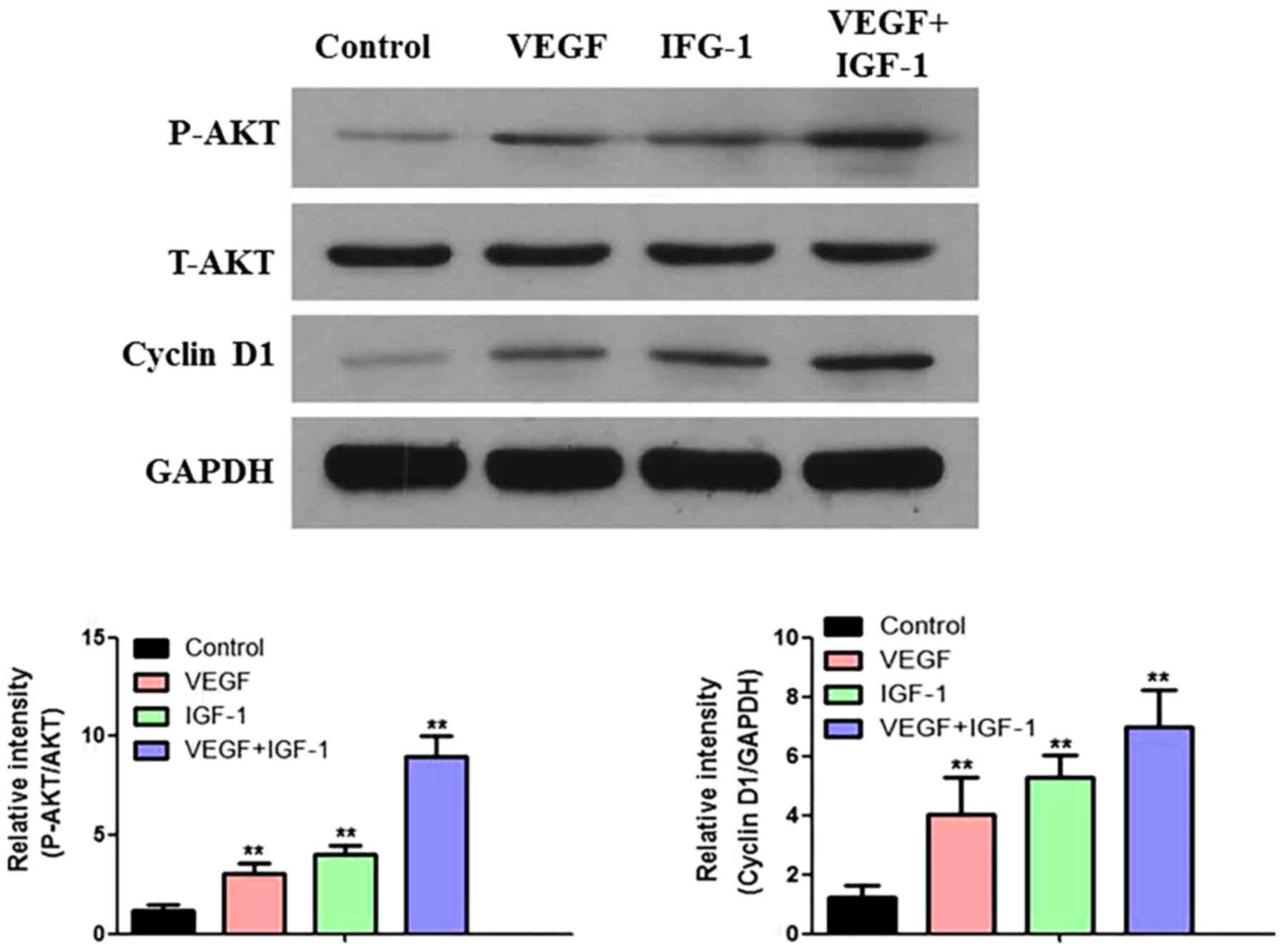

Effect of VEGF and IGF-1 on the AKT

signaling pathway in hCDPSCs in vitro

Compared with the control group, the expression

levels of p-AKT and cyclin D1 were increased upon addition of

either VEGF or IGF-1 alone, whereas the expression of these two

proteins was further increased by adding VEGF and IGF-1 in

combination to activate the AKT signaling pathway of the hCDPSCs

(Fig. 6). These results

demonstrated that the combination of VEGF and IGF-1 elicited a

synergistic effect (Fig. 6).

| Figure 6.Effect of AKT signaling pathway in

hCDPSCs upon treatment with VEGF and IGF-1. The protein expression

levels of P-AKT, T-AKT and cyclin D1 were detected by western

blotting, and the relative protein expression levels were

calculated. **P<0.01 vs. control. For the description of the

experimental groups (Control, VEGF, IGF-1 and VEGF+IGF-1), see the

Results section. hCDPSCs, human carious dental pulp stem cells;

IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial

growth factor; P-AKT, phosphorylated AKT; T-AKT, total AKT. |

Discussion

Currently, hDPSCs are commonly used as ‘seed’ cells

in bone tissue engineering due to their high self-renewal capacity

and stemness (3,31). hCDPSCs are a unique type of dental

stem cell, since they are derived from the pulp in deep carious

teeth (7,8). This special environmental stimulus

enables the stronger proliferation and osteogenic differentiation

capability of hCDPSCs, and therefore they are now recognized as a

potential source for regenerative medicine (7,8).

GFs are critical in tissue regeneration, as they

have important roles in regulating cell functions (32,33).

Previous studies have reported that the combination of IGF-1 and

other GFs (such as PDGF-B or BMP-2) may affect cell proliferation,

promote osteogenesis, and help the reconstruction of

toothsupporting tissues (34–36).

IGF-1 has been identified to stimulate osteogenic differentiation

via the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway,

suggesting that IGF-1 has a role in regeneration of the periodontal

tissue (37). VEGF has the

potential of triggering neovascularization, which is able to

regulate both normal and pathological conditions, and provides

blood supply for tissue regeneration (38,39).

Angiogenesis is essential for bone reconstruction, as new bone

formation relies on a suitable blood supply to provide cells and

nutrients (40). Therefore, the

selection of suitable GFs has become an important research focus in

tissueengineering therapy.

In the present study, the CCK8 assay results

demonstrated that the combination of VEGF and IGF-1 exerted a

synergistic effect on proliferation. Transwell assay revealed that

the migratory ability of hCDPSCs upon combined treatment of VEGF

and IGF-1 was markedly stronger compared with that of treating with

VEGF or IGF-1 alone. This finding indicated that there was a

synergistic effect resulting from treating the cells with VEGF and

IGF-1 in combination. It has been previously shown that, when

either VEGF (25 ng/ml) or IGF-I (100 ng/ml) were used, MSCs

exhibited the strongest proliferative capacity (19–21).

Furthermore, it was reported that the combined use of VEGF and

IGF-1 enhanced osteogenic PDPCs and S-MSCs (22). Therefore, based on the findings of

these previous studies, a combination of IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) and VEGF

(25 ng/ml) was used in the present study to investigate the effects

of IGF-1 and VEGF on proliferation, migration, osteogenesis and

vascularization of hCDPSCs.

RUNX2 is a highly conserved transcription factor,

known as the most important regulator in osteoblast and odontoblast

differentiation (41). Runx2

activates boneassociated genes and promotes mineralization in the

early stage of osteoblast differentiation (41,42).

ALP is the enzyme that is predominantly involved in both bone and

tooth mineralization, and elevated levels of ALP may be considered

as an early marker of odontoblast differentiation and dentin

formation (43). BSP is an

important product during osteogenic differentiation, which may

clearly indicate the level of ALP (44). The results of RT-PCR and western

blotting in the present study demonstrated that VEGF and IGF-1

exerted a synergistic effect on bone formation, which was more

effective than using either of the drugs alone. It has been

reported that the combined use of VEGF and IGF-1 could induce the

differentiation of S-MSCs into osteoblasts, and that the IGF-1 and

insulin signaling pathways may function as important mediators in

terms of Runx2 activity (45).

The results from the alizarin red and ALP staining

experiments in the present study revealed that the combined use of

VEGF and IGF-1 could promote the osteogenesis of hCDPSCs. VEGF has

been widely studied as a major regulator in angiogenesisassociated

processes, in which the molecule exerts both direct and indirect

functions (46). VEGF stimulates

cell proliferation and migration, whereas on the other hand, it

increases the permeability of blood vessels and allows plasma

proteins to leak out of blood vessels, a process that serves an

important role in remodeling the extracellular matrix to adapt to

angiogenesis (46,47). The addition of VEGF during the

early stage of bone repair may lead to an improvement in the blood

supply of the microenvironment and the formation of new bone

(47). The results of the present

study showed that the single application of either VEGF or IGF-1

was sufficient to promote vascular differentiation of hCDPSCs,

whereas the combined use of VEGF and IGF-1 elicited a synergistic

effect.

The PI3K/Akt pathway is a tyrosine kinase

receptor-mediated signaling system, which exists widely in various

types of cell (23). It is an

important signal-transduction pathway involved in the regulation of

cell growth, proliferation and differentiation (24). Activated Akt can induce changes in

a series of downstream factors [including mammalian target of

rapamycin, (mTOR), glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), Bax, NF-κB,

caspases, etc.] and participate in the regulation of cell growth,

differentiation, division and migration (24). The phosphorylation level of Akt may

also reflect the activity of whole signaling pathway (48). It has been shown that IGF-1

promotes the vascular differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells

and endothelial cells via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (48). The activation of autophagic

activity is able to enhance the osteogenic differentiation of

hBMSCs, thereby providing a novel therapeutic target for

osteoporosis treatment (49).

Therefore, it is possible to surmise that activation of the

PI3K-AKT pathway may give rise to the observed effects associated

with the mTOR pathway and autophagy activity during the osteogenic

differentiation of hCDPSCs.

In conclusion, the present study has identified that

the AKT signaling pathway may be activated by the use of VEGF or

IGF-1 alone, whereas the AKT signaling pathway can be further

activated by the combined use of VEGF and IGF-1. This suggests that

the combined use of VEGF and IGF-1 may have the additive effects

through AKT signaling pathway.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by grant from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 8187041227).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

BW and WL designed the study. WL, WX and JL guided

the experiments. WL, YC and YP performed the experiments. WL and WX

collected and processed the clinical data. JL, YC and YP analyzed

and interpreted the patient data. BW and WL wrote the paper, and BW

reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol was performed according to a

standard protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the Southern

Medical University. All patients signed written informed consent

forms.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Xuan K, Li B, Guo H, Sun W, Kou X, He X,

Zhang Y, Sun J, Liu A, Liao L, et al: Deciduous autologous tooth

stem cells regenerate dental pulp after implantation into injured

teeth. Sci Transl Med. 10:eaaf32272018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Xia Y, Chen H, Zhang F, Bao C, Weir MD,

Reynolds MA, Ma J, Gu N and Xu HHK: Gold nanoparticles in

injectable calcium phosphate cement enhance osteogenic

differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells. Nanomedicine.

14:35–45. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Martin-Del-Campo M, Rosales-Ibanez R,

Alvarado K, Sampedro JG, Garcia-Sepulveda CA, Deb S, San Román J

and Rojo L: Strontium folate loaded biohybrid scaffolds seeded with

dental pulp stem cells induce in vivo bone regeneration in critical

sized defects. Biomater Sci. 4:1596–1604. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Farges JC, Alliot-Licht B, Renard E,

Ducret M, Gaudin A, Smith AJ and Cooper PR: Dental pulp defence and

repair mechanisms in dental caries. Mediators Inflamm.

2015:2302512015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fernandez MR, Goettems ML, Demarco FF and

Correa MB: Is obesity associated to dental caries in Brazilian

schoolchildren? Braz Oral Res. 31:e832017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Louvrier A, Euvrard E, Nicod L, Rolin G,

Gindraux F, Pazart L, Houdayer C, Risold PY, Meyer F and Meyer C:

Odontoblastic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells from

healthy and carious teeth on an original PCL-based 3D scaffold. Int

Endod J. 51 (Suppl 4):e252–e263. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gnanasegaran N, Govindasamy V and Abu

Kasim NH: Differentiation of stem cells derived from carious teeth

into dopaminergic-like cells. Int Endod J. 49:937–949. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Werle SB, Lindemann D, Steffens D, Demarco

FF, de Araujo FB, Pranke P and Casagrande L: Carious deciduous

teeth are a potential source for dental pulp stem cells. Clin Oral

Investig. 20:75–81. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ma D, Gao J, Yue J, Yan W, Fang F and Wu

B: Changes in proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of stem

cells from deep caries in vitro. J Endod. 38:796–802. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sinclair KL, Mafi P, Mafi R and Khan WS:

The use of growth factors and mesenchymal stem cells in

orthopaedics: In particular, their use in Fractures and Non-Unions:

A systematic review. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 12:312–325. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Augustyniak E, Trzeciak T, Richter M,

Kaczmarczyk J and Suchorska W: The role of growth factors in stem

cell-directed chondrogenesis: A real hope for damaged cartilage

regeneration. Int Orthop. 39:995–1003. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hankenson KD, Gagne K and Shaughnessy M:

Extracellular signaling molecules to promote fracture healing and

bone regeneration. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 94:3–12. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kim Y and Liu JC: Protein-engineered

microenvironments can promote endothelial differentiation of human

mesenchymal stem cells in the absence of exogenous growth factors.

Biomater Sci. 4:1761–1772. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Trosan P, Javorkova E, Zajicova A, Hajkova

M, Hermankova B, Kossl J, Krulova M and Holan V: The Supportive

Role of insulin-like growth factor-I in the differentiation of

murine mesenchymal stem cells into corneal-like cells. Stem Cells

Dev. 25:874–881. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen CY, Tseng KY, Lai YL, Chen YS, Lin FH

and Lin S: Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor 1 enhanced

the osteogenic capability of aging bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells. Theranostics. 7:1598–1611. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Shi C, Zhao Y, Yang Y, Chen C, Hou X, Shao

J, Yao H, Li Q, Xia Y and Dai J: Collagen-binding VEGF targeting

the cardiac extracellular matrix promotes recovery in porcine

chronic myocardial infarction. Biomater Sci. 6:356–363. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Rybalko VY, Pham CB, Hsieh PL, Hammers DW,

Merscham-Banda M, Suggs LJ and Farrar RP: Controlled delivery of

SDF-1α and IGF-1: CXCR4(+) cell recruitment and functional skeletal

muscle recovery. Biomater Sci. 3:1475–1486. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Feng X, Huang D, Lu X, Feng G, Xing J, Lu

J, Xu K, Xia W, Meng Y, Tao T, et al: Insulin-like growth factor 1

can promote proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human

dental pulp stem cells via mTOR pathway. Dev Growth Differ.

56:615–624. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yu Y, Mu J, Fan Z, Lei G, Yan M, Wang S,

Tang C, Wang Z, Yu J and Zhang G: Insulin-like growth factor 1

enhances the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human

periodontal ligament stem cells via ERK and JNK MAPK pathways.

Histochem Cell Biol. 137:513–525. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bai Y, Li P, Yin G, Huang Z, Liao X, Chen

X and Yao Y: BMP-2, VEGF and bFGF synergistically promote the

osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal

stem cells. Biotechnol Lett. 35:301–308. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lee JH, Um S, Jang JH and Seo BM: Effects

of VEGF and FGF-2 on proliferation and differentiation of human

periodontal ligament stem cells. Cell Tissue Res. 348:475–484.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Dicarlo M, Bianchi N, Ferretti C, Orciani

M, Di Primio R and Mattioli-Belmonte M: Evidence supporting a

paracrine effect of IGF-1/VEGF on human mesenchymal stromal cell

commitment. Cells Tissues Organs. 201:333–341. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang J, Liu X, Li H, Chen C, Hu B, Niu X,

Li Q, Zhao B, Xie Z and Wang Y: Exosomes/tricalcium phosphate

combination scaffolds can enhance bone regeneration by activating

the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 7:1362016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wu X, Zheng S, Ye Y, Wu Y, Lin K and Su J:

Enhanced osteogenic differentiation and bone regeneration of

poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) by graphene via activation of

PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β/β-catenin signal circuit. Biomater Sci.

6:1147–1158. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Iyer S, Viernes DR, Chisholm JD, Margulies

BS and Kerr WG: SHIP1 regulates MSC numbers and their osteolineage

commitment by limiting induction of the PI3K/Akt/βcatenin/Id2 axis.

Stem Cells Dev. 23:2336–2351. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ma D, Cui L, Gao J, Yan W, Liu Y, Xu S and

Wu B: Proteomic analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from normal and

deep carious dental pulp. PLoS One. 9:e970262014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Pan Y, Chen J, Yu Y, Dai K, Wang J and Liu

C: Enhancement of BMP-2-mediated angiogenesis and osteogenesis by

2-N,6-O-sulfated chitosan in bone regeneration. Biomater Sci.

6:431–439. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gangadaran P, Rajendran RL, Lee HW,

Kalimuthu S, Hong CM, Jeong SY, Lee SW, Lee J and Ahn BC:

Extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cells activates VEGF

receptors and accelerates recovery of hindlimb ischemia. J Control

Release. 264:112–126. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Thekkeparambil Chandrabose S, Sriram S,

Subramanian S, Cheng S, Ong WK, Rozen S, Kasim NHA and Sugii S:

Amenable epigenetic traits of dental pulp stem cells underlie high

capability of xeno-free episomal reprogramming. Stem Cell Res Ther.

9:682018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Schreier C, Rothmiller S, Scherer MA,

Rummel C, Steinritz D, Thiermann H and Schmidt A: Mobilization of

human mesenchymal stem cells through different cytokines and growth

factors after their immobilization by sulfur mustard. Toxicol Lett.

293:105–111. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Alarcin E, Lee TY, Karuthedom S, Mohammadi

M, Brennan MA, Lee DH, Marrella A, Zhang J, Syla D, Zhang YS, et

al: Injectable shear-thinning hydrogels for delivering osteogenic

and angiogenic cells and growth factors. Biomater Sci. 6:1604–1615.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Moeller M, Pink C, Endlich N, Endlich K,

Grabe HJ, Volzke H, Dörr M, Nauck M, Lerch MM, Köhling R, et al:

Mortality is associated with inflammation, anemia, specific

diseases and treatments, and molecular markers. PLoS One.

12:e1759092017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Schminke B, Vom Orde F, Gruber R,

Schliephake H, Burgers R and Miosge N: The pathology of bone tissue

during peri-implantitis. J Dent Res. 94:354–361. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chang PC, Cirelli JA, Jin Q, Seol YJ,

Sugai JV, D'Silva NJ, Danciu TE, Chandler LA, Sosnowski BA and

Giannobile WV: Adenovirus encoding human platelet-derived growth

factor-B delivered to alveolar bone defects exhibits safety and

biodistribution profiles favorable for clinical use. Hum Gene Ther.

20:486–496. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang C, Hong FF, Wang CC, Li L, Chen JL,

Liu F, Quan RF and Wang JF: TRIB3 inhibits proliferation and

promotes osteogenesis in hBMSCs by regulating the ERK1/2 signaling

pathway. Sci Rep. 7:103422017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen FM, Chen R, Wang XJ, Sun HH and Wu

ZF: In vitro cellular responses to scaffolds containing two

microencapulated growth factors. Biomaterials. 30:5215–5224. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Koo T, Park SW, Jo DH, Kim D, Kim JH, Cho

HY, Kim J, Kim JH and Kim JS: CRISPR-LbCpf1 prevents choroidal

neovascularization in a mouse model of age-related macular

degeneration. Nat Commun. 9:18552018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Du J, Xie P, Lin S, Wu Y, Zeng D, Li Y and

Jiang X: Time-Phase sequential utilization of adipose-derived

mesenchymal stem cells on mesoporous bioactive glass for

restoration of critical size bone defects. ACS Appl Mater

Interfaces. 10:28340–28350. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Deng L, Hu G, Jin L, Wang C and Niu H:

Involvement of microRNA-23b in TNF-α-reduced BMSC osteogenic

differentiation via targeting runx2. J Bone Miner Metab.

36:648–660. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kim KM and Jang WG: Zaluzanin C (ZC)

induces osteoblast differentiation through regulating of osteogenic

genes expressions in early stage of differentiation. Bioorg Med

Chem Lett. 27:4789–4793. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wang Z, Tan J, Lei L, Sun W, Wu Y, Ding P

and Chen L: The positive effects of secreting cytokines IL-17 and

IFN-γ on the early-stage differentiation and negative effects on

the calcification of primary osteoblasts in vitro. Int

Immunopharmacol. 57:1–10. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Han Y, Jin Y, Lee SH, Khadka DB, Cho WJ

and Lee KY: Berberine bioisostere Q8 compound stimulates osteoblast

differentiation and function in vitro. Pharmacol Res. 119:463–475.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Qiao M, Shapiro P, Kumar R and Passaniti

A: Insulin-like growth factor-1 regulates endogenous RUNX2 activity

in endothelial cells through a phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase/ERK-dependent and Akt-independent signaling pathway. J

Biol Chem. 279:42709–42718. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Heldin J, O'Callaghan P, Hernández Vera R,

Fuchs PF, Gerwins P and Kreuger J: FGD5 sustains vascular

endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) signaling through inhibition of

proteasome-mediated VEGF receptor 2 degradation. Cell Signal.

40:125–132. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gurkan A, Tekdal GP, Bostanci N and

Belibasakis GN: Cytokine, chemokine, and growth factor levels in

peri-implant sulcus during wound healing and osseointegration after

piezosurgical versus conventional implant site preparation:

Randomized, controlled, split-mouth trial. J Periodontol.

90:616–626. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lin S, Zhang Q, Shao X, Zhang T, Xue C,

Shi S, Zhao D and Lin Y: IGF-1 promotes angiogenesis in endothelial

cells/adipose-derived stem cells coculture system with activation

of PI3K/Akt signal pathway. Cell Prolif. 50:2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

48

|

Wan Y, Zhuo N, Li Y, Zhao W and Jiang D:

Autophagy promotes osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cell derived from osteoporotic vertebrae. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 488:46–52. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Pantovic A, Krstic A, Janjetovic K, Kocic

J, Harhaji-Trajkovic L, Bugarski D and Trajkovic V: Coordinated

time-dependent modulation of AMPK/Akt/mTOR signaling and autophagy

controls osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem

cells. Bone. 52:524–531. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|