Introduction

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS), also known as

polyposis pigmentation-alopecia-onycholrophia syndrome, is a

syndrome distinguished by gastrointestinal (GI) polyposis and

ectodermal changes (1). It has been

demonstrated that the incidence of CCS is 1 in a million (2). CCS affects more men compared with women,

with a ratio of 3:2, and commonly occurs in the fifth decade of

life, with a mean age of onset between 50–60 years (3). Cronkhite and Canada first described CCS

in 1955, and CCS is a rare disease of unknown etiology (4). Following its identification, >500

cases have been described in the literature (5). Although the incidence of CCS is low, it

is associated with a high mortality; 5-year mortality may be as

high as 55% (6). At present, the

treatments for CSS include corticosteroids, nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor

antagonists, hyperalimentation, cromolyn sodium, antibiotics,

anabolic steroids, surgery, 5-aminosalicylate acid, antitumor

necrosis factor α agents and the eradication of Helicobacter

pylori, or a combination of these therapies (7).

In the present case study, a 58-years-old male with

CCS diagnosed at the Department of Gastroenterology, The Third

Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Hunan, China) is

reported. The patient experienced a history of diarrhea and

hematochezia for 4 months, with abdominal pain for 1 month and

additional nail and toenail loss for half a month. The clinical,

endoscopic and histological data confirmed the diagnosis. The

patient was treated with proton pump inhibitors, gastric mucosal

protective agents, endoscopic electrocision of colon polyps,

glutamine capsule, nutrition support and Bifid triple viable

capsules. The patient eventually recovered.

Case report

A 58-year-old male visited The Third Xiangya

Hospital of Central South University (Hunan, Changsha, China) on

June 6, 2014, with the primary complaint of diarrhea and

hematochezia for 4 months, abdominal pain for 1 month and nail and

toenail loss for half a month. Informed written consent was

obtained from the patient for publication of the present study. The

patient additionally felt tiredness and had experienced a weight

loss of 5 kg in half a month. There were no abnormalities,

including GI polyposis or colorectal cancer, in the family history

of the individual. However, the patient had a history of alcoholic

cirrhosis for >10 years, and 13 years prior to visiting The

Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University he had suffered

from gastrorrhagia. The patient had been drinking 400 ml rice wine

and smoking 20 cigarettes/day for 40 years.

Physical examination revealed that the patient was

suffering from malnutrition, he was emaciated and had an anemic

appearance, with a dermatological triad of hyperpigmentation in his

oral mucosa (Fig. 1) and a brown

pigmentation in his palms and feet (Fig.

2). Atrophy of fingernail and toenails were later observed, in

addition to eventual toenail and nail loss.

Laboratory tests revealed that the patient's white

blood cell count was 7.5×109/l (normal range,

4–10×109/l), platelet count was 216×109/l

(normal range, 100–300×109/l), hemoglobin was 61 g/l,

fecal occult blood test (+), C-reactive protein and erythrocyte

sedimentation rate were normal, serum albumin was 28.5 g/l (normal

range, 40–60 g/l) and serum total protein was 46.1 g/l (normal

range, 60–80 g/l).

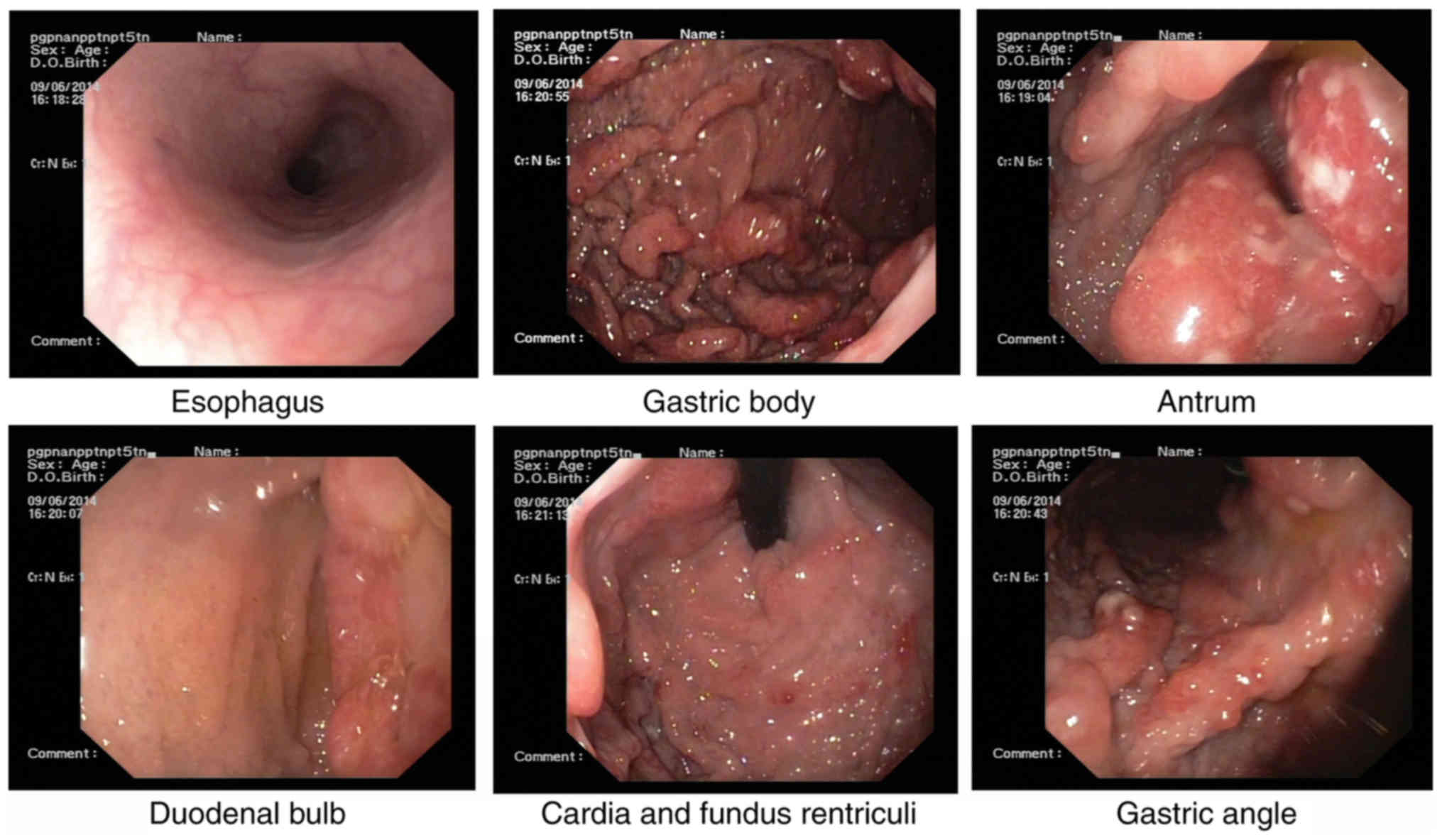

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, performed for the

further evaluation of the GI tract, revealed multiple nodules and

granular polyps in the stomach and duodenum (Fig. 3).

In the present study, biopsy specimens were fixed in

4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature, dehydrated (75% ethanol

for 45 min, 85% ethanol for 45 min, 95% ethanol for 45 min, 100%

ethanol for 45 min, immersed in 100% isobutanol overnight and

lastly transferred to 100% butanol for 3 h) and embedded in

paraffin. Paraffin-embedded sections measuring 4 µm-thick were then

stained with 0.5% hematoxylin for 2 min and 1% eosin for 1 min at

room temperature (H&E). Finally, the sections were observed

under a light microscope (magnification, ×100; Olympus BX51;

Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan,).

Biopsy specimens from the gastric antrum mucosa

displayed mucosal chronic inflammation, edematous stroma with

inflammatory cell infiltration, small blood vessel proliferation

and regional glandular epithelial hyperplasia (Fig. 4).

As these findings could not confirm the diagnosis, a

further colonoscopy was performed for differential diagnosis, which

revealed numerous, dense polyps throughout the terminal ileum,

colon and rectum (Figs. 5 and

6). Biopsy specimens from the colon

displayed colorectal villus-tubiform adenoma, glandular epithelial

hyperplasia and mild-to-moderate atypical hyperplasia (Fig. 7). GI radiography revealed that the GI

multiple filling defect may be a result of the multiple polyps

(Fig. 8).

The patient presented with diffuse GI polyposis

associated with ectodermal changes including hyperpigmentation and

onychatrophy, and these findings resulted in the diagnosis of CCS.

We intended to treat the patient with corticosteroids, but he

refused due to the potential side-effects. Therefore, the patient

was treated with proton pump inhibitors to inhibit gastric acid

secretion (40% pantoprazole sodium, 100 ml, was administered

intravenously, once a day), gastric mucosal protective agents to

protect gastric mucosa (Hydrotalcite Chewable Tablets, 1 g, orally,

three times a day), endoscopic electrocision of colon polyps,

glutamine to protect the intestinal intima (3% alanine glutamine,

50 ml, ivgtt, once a day) and nutritional support (7% amino acid

compound infusion18AA-II, 250 ml ivgtt, once a day). We also used

bifid triple viable capsules to modulate intestinal flora (Bifid

triple viable capsules, 420 mg, orally, three times a day). The

patient eventually recovered and was discharged from the hospital

within 1 month.

Following 1 month of treatment, gastroscopy revealed

gastric duodenal mucosal swelling and mucous with nodular and

polypoid hyperplasia (Fig. 9). Biopsy

specimens from the gastric antrum mucosal displayed mucosal chronic

inflammation, regional glandular epithelial hyperplasia and a

growth tendency of inflammatory hyperplastic polyps with

inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig.

10). Colonoscopy revealed terminal ileum, colon and rectal

hyperplastic polyps, with colon polyps emerging subsequent to

endoscopic mucosal resection and titanium clip clipping operation

(Figs. 11 and 12). Biopsy specimens from the colon

displayed a tubular adenoma 40 cm from the anus and ascending

colon. Additionally, part of the glandular epithelium had

light-mild atypical hyperplasia, a stroma of acidophilic ball

infiltration (in the terminal ileum and appendix) and mucosal

chronic inflammation (in the appendix) within the interstitial

eosinophilic inflammation (Fig. 13).

In order to exclude lymphoma, ultrasonic gastroscopy was advised,

and the patient was further advised to take corticosteroids, but he

refused and asked for discharging from the hospital following 1

month of treatment.

Discussion

Cronkhite and Canada first described CCS in 1955

(4). CCS is a rare, acquired,

nonhereditary syndrome with diffuse GI polyposis associated with

ectodermal changes, including hyperpigmentation, alopecia and

onychatrophy (8,9). Additionally, it has been reported that

the CCS has been associated with poor prognosis and

life-threatening malignant complications (7). The etiology of CCS remains unknown, and

genetic abnormalities (10), mental

stress (11), immune dysregulation

(12,13), low turnover cell differentiation

(14) and fatigue are regarded as

triggering factors for CCS (2).

CCS may occur in all ethnic groups, and the

estimated incidence of CCS is extremely rare, approximately one

case in a million individuals (2). At

present, >500 cases of CCS have been reported globally, and

patients from Europe and Asia are most frequently affected

(2). Of all reported cases of CCS,

75% have been from Japan (15).

Furthermore, it has been reported that CCS is

sporadic and there is no strong evidence to suggest a hereditary

predisposition (2). CCS affects more

men compared with women, with a ratio of 3:2, and commonly occurs

in the fifth decade of life. A total of 80% of patients are >50

years of age at the time of presentation (6). According to a previous study, it has

been revealed that the mean age of onset of CCS is 63.5 (range,

31–86) years (7).

CCS is also known as polyposis

pigmentation-alopecia-onycholrophia syndrome, and GI polyposis and

ectodermal changes are its two main features (16). For patients with CCS, diarrhea is the

most common initial symptom, which may develop to substantially

watery diarrhea, followed with symptoms of malabsorption, including

weakness, anemia, weight loss, edema and dysgeusia (17). Subsequent endoscopic and radiological

evaluation may reveal sessile polyps throughout the GI tract

(18).

Histopathological reviews of biopsies obtained from

these polyps revealed that these polyps are similar to that of

juvenile, adenomatous polyps or inflammatory type polyps, however

they were additionally marked by striking stromal and lamina

propria edematous changes, eosinophilic inflammation, were

cystically dilated and had distorted glands with inflammatory

infiltration (7).

Ectodermal changes include alopecia, nail dystrophy

and hyperpigmentation. These changes often occur later during the

disease progression, usually several weeks or months subsequent to

the GI symptoms (8). Consistent with

this, in the present case study, the patient initially experienced

diarrhea and hematochezia, followed by abdominal pain, nail and

toenail loss, onychatrophy and hyperpigmentation.

Complications of CCS include GI bleeding with

anemia, intussusception, hypoproteinemia, rectal prolapse,

malabsorption, electrolyte turbulences, enteropathy and

hypovitaminosis (19). In addition,

CCS was reported to be associated with various rare complications

including recurrent severe acute pancreatitis (20), GI tract cancer, portal thrombosis, a

high titer of antinuclear antibodies and membranous

glomerulonephritis (21). Among them,

the risk of GI tract tumor types substantially increases. It has

been reported that between 1980 and 2011, there were 383 patients

diagnosed with CCS in Japan, and of these patients, 10.4% (40

patients) of them were also diagnosed with gastric cancer and 69

lesions (51 patients) were also diagnosed with colon cancer

(15). Due to this, endoscopic

surveillance is strongly recommended.

Differential diagnosis of CCS includes Menetrier

disease, familial adenomatous polyposis, juvenile polyposis, Cowden

syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease,

Whipple disease and small intestinal lymphoma (22–24). In

the present case, the patient was initially diagnosed with familial

polyposis, but eventually was diagnosed with CCS due to the

dermatological triad of hyperpigmentation in oral mucosa (Fig. 1), brown pigmentation in palms and feet

(Fig. 2) and toenail and nail

loss.

Due to the rarity of CCS, evidence-based therapies

have yet to be developed, however, to the best of our knowledge,

there are no systematic investigations of medical or surgical

interventions. The treatments and strategy of CSS currently include

corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump

inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists, hyperalimentation, cromolyn

sodium, antibiotics, anabolic steroids, surgery, 5-aminosalicylate

acid, antitumor necrosis factor α agents and the eradication of

Helicobacter pylori and combinations of these therapies

(7). Steroids are considered to be

the mainstay of medical treatment, however until now, there have

been no guidelines for the recommended dose and duration of their

use.

The prognosis of CCS is poor, with a 5-year

mortality rate of 55% and the majority of mortality being

associated with malnutrition, hypoalbuminemia, repetitive

infection, sepsis, heart failure and GI bleeding (8). The natural history of CCS appears to be

substantially improved owing to the sufficient dose and duration of

corticosteroid therapy accompanied by nutritional support and

periodic endoscopic surveillance (7).

Altogether, when a patient presents with the

symptoms of CCS, early diagnosis and treatment of CCS is necessary,

in addition to receiving endoscopic follow-up or polypectomy when

necessary. In the present case, the results from a telephone

follow-up implied that the patient is in a good condition; he feels

well and does not experience any symptoms, therefore has refused to

return to the hospital for a follow-up.

CCS is a rare but serious disease with an increased

mortality rate if clinical intervention is received late (25). Delays in diagnosis are common,

primarily due to the non-familiarity of physicians with this rare

entity, resulting in a poor outcome (26). This patient did not present with the

cardinal manifestations of CCS which resulted in a delayed

diagnosis. Therefore, in order to avoid the misdiagnosis of CCS

without typical features in future, physicians are recommended to

analyze the histopathology of the polyps and to search for the

presence of characteristic dermatological changes: The changes in

the shape and colour of toenail and nail abnormalities.

Acknowledgements

The present case study was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81272736, 81670504

and 81472287), the National Key Clinical Specialty of National

Health and Family Planning Commission and The Third Xiangya

Hospital ‘Xiangya Doctors Heritage Plan’.

References

|

1

|

Sweetser S, Alexander GL and Boardman LA:

A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome presenting with adenomatous and

inflammatory colon polyps. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

7:460–464. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Goto A: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome:

Epidemiological study of 110 cases reported in Japan. Nihon Geka

Hokan. 64:3–14. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ward EM and Wolfsen HC: Review article:

The non-inherited gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 16:333–342. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gardner EJ, Burt RW and Freston JW:

Gastrointestinal polyposis: Syndromes and genetic mechanisms. West

J Med. 132:488–499. 1980.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Rubio CA and Björk J: Cronkhite-Canada

syndrome-A case report. Anticancer Res. 36:4215–4217.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ, Ruprecht

RM, Rajacich GM and Schwabe AD: The Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. An

analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55

patients. Medicine. 61:293–309. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Watanabe C, Komoto S, Tomita K, Hokari R,

Tanaka M, Hirata I, Hibi T, Kaunitz JD and Miura S: Endoscopic and

clinical evaluation of treatment and prognosis of Cronkhite-Canada

syndrome: A Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol.

51:327–336. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yun SH, Cho JW, Kim JW, Kim JK, Park MS,

Lee NE, Lee JU and Lee YJ: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated

with serrated adenoma and malignant polyp: A case report and a

literature review of 13 cronkhite-Canada syndrome cases in Korea.

Clin Endosc. 463:301–305. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wen XH, Wang L, Wang YX and Qian JM:

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: Report of six cases and review of

literature. World J Gastroenterol. 20:7518–7522. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Patil V, Patil LS, Jakareddy R, Verma A

and Gupta AB: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: A report of two familial

cases. Indian J Gastroenterol. 32:119–122. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Murata I, Yoshikawa I, Endo M, Tai M,

Toyoda C, Abe S, Hirano Y and Otsuki M: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome:

Report of two cases. J Gastroenterol. 35:706–711. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sweetser S, Ahlquist DA, Osborn NK,

Sanderson SO, Smyrk TC, Chari ST and Boardman LA: Clinicopathologic

features and treatment outcomes in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome:

Support for autoimmunity. Dig Dis Sci. 57:496–502. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Riegert-Johnson DL, Osborn N, Smyrk T and

Boardman LA: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome hamartomatous polyps are

infiltrated with IgG4 plasma cells. Digestion. 75:96–97. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Freeman K, Anthony PP, Miller DS and Warin

AP: Cronkhite Canada syndrome: A new hypothesis. Gut. 26:531–536.

1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Matsui S, Kibi M, Anami E, Anami T,

Inagaki Y, Kanouda A, Yoshinaga H, Watanabe A, Sugahara A, Mukai H,

et al: A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with multiple colon

adenomas and early colon cancers. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi.

108:778–786. 2011.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang J, Zhao L, Ma N, Che J, Li H and Cao

B: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with colon cancer

metastatic to liver: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore).

968:e74662017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Chakrabarti S: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome

(CCS)-A rare case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 9:OD08–OD09.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Goto A, Mimoto H, Shibuya C and Matsunami

E: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: An analysis of clinical features and

follow-up studies of 80 cases reported in Japan. Nihon Geka Hokan.

57:506–526. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Seshadri D, Karagiorgos N and Hyser MJ: A

case of cronkhite-Canada syndrome and a review of gastrointestinal

polyposis syndromes. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 8:197–201.

2012.

|

|

20

|

Yasuda T, Ueda T, Matsumoto I, Shirasaka

D, Nakajima T, Sawa H, Shinzeki M, Kim Y, Fujino Y and Kuroda Y:

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome presenting as recurrent severe acute

pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 67:570–572. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Takeuchi Y, Yoshikawa M, Tsukamoto N,

Shiroi A, Hoshida Y, Enomoto Y, Kimura T, Yamamoto K, Shiiki H,

Kikuchi E and Fukui H: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with colon cancer,

portal thrombosis, high titer of antinuclear antibodies, and

membranous glomerulonephritis. J Gastroenterol. 38:791–795. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sweetser S and Boardman LA:

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: An acquired condition of

gastrointestinal polyposis and dermatologic abnormalities.

Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 8:201–203. 2012.

|

|

23

|

Samet JD, Horton KM, Fishman EK and

Iacobuzio-Donahue CA: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: Gastric

involvement diagnosed by MDCT. Case Rep Med. 2009:1487952009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kopáčová M, Urban O, Cyrany J, Laco J,

Bureš J, Rejchrt S, Bártová J and Tachecí I: Cronkhite-Canada

syndrome: Review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract.

2013:8568732013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Iqbal U, Chaudhary A, Karim MA, Anwar H

and Merrell N: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: A rare cause of chronic

diarrhea. Gastroenterology Res. 10:196–198. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Fan RY, Wang XW, Xue LJ, An R and Sheng

JQ: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyps infiltrated with IgG4-positive

plasma cells. World J Clin Cases. 4:248–252. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|