Introduction

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) is a diagnostic

challenge, despite recent advances in diagnostic modalities

(1,2). FUO is defined as a prolonged febrile

illness without a recognized cause, even after comprehensive

laboratory tests and imagining workup. The current definition of

FUO is as follows: i) Body temperature of ≥38.3˚C on at least two

occasions; ii) duration of illness of ≥3 weeks; iii) not an

immunocompromised setting; and iv) uncertain diagnosis despite

thorough history taking, physical examination and laboratory

assessments. These laboratory measures include the erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), hemoglobin,

platelet count, leukocyte count and differentiation, electrolyte

levels, creatinine level, total serum protein, protein

electrophoresis, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase,

lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), ferritin, microscopic urinalysis,

blood cultures and urine cultures. The most common radiological

investigation includes chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasonography.

Additional tests may include the tuberculin test or an interferon-γ

release assay (3,4). The cause of FUO may be multifactorial

and can be subdivided into four categories: Infections,

malignancies, noninfectious inflammatory processes and

miscellaneous causes (5). FUO is

closely related to inflammation of unknown origin (IUO), and the

causes and workups are the same for both FUO and IUO (6). Early identification of the cause of

FUO is important for guiding the diagnostic workup and for

initiating early and appropriate treatment without notable impacts

on patient care (7).

Conventional anatomic imaging modalities, such as

ultrasonography, and cross-sectional imaging with CT and MRI, are

used as primary diagnostic modalities to manage FUO; however, they

have limited sensitivity and specificity (8). Therefore, a significant number of

patients with FUO (30-50%) leave the hospital without specific

diagnoses (9). Positron emission

tomography (PET)/CT using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

(18FDG) is a well-accepted clinical tool for routine use

in a wide range of malignancies. 18FDG is a glucose

analogue that accumulates in cells with high metabolic

requirements, such as tumor and inflammatory cells.

18FDG PET/CT is currently considered a useful

noninvasive imaging modality for the evaluation of patients with

FUO (10-13).

However, only a few studies have assessed 18FDG PET/CT

in patients with FUO. Furthermore, most of these studies were

performed in developed countries and the geographic area of the

study strongly influenced the determination of the final diagnosis.

Studies have shown that the cause of FUO in developing countries

was most often infectious (14,15),

whereas noninfectious inflammatory processes were the most common

drivers of FUO in developed countries.

Several meta-analyses have reported the positive

impact of FDG PET/CT in establishing the final diagnosis of

patients with FUO/IUO. The diagnostic yield of PET CT/CT in this

population is 56-60%, which is ≥30% higher than that of

conventional CT (16,17). However, most studies are

retrospective studies, with significant heterogeneity of baseline

study characteristics, definition of FUO/IUO and imaging parameters

(18,19). In certain studies, FDG PET/CT was

the only imaging modality that was able to establish a final

diagnosis (18,19). The vast majority of the studies

investigated the diagnostic value of PET/CT, with only a few

studies investigating the cost-effectiveness of FDG PET/CT in the

diagnostic work-up of patients with FUO (20). Based on the previous studies,

patients with FUO/IUO are a challenging, heterogeneous population

with a wide variety of differential diagnoses. Furthermore, there

is a lack of an established work-up strategy. According to

published data, it is important to further investigate the

diagnostic impact of PET/CT, the cost-effectiveness, and when and

how to perform PET/CT in the setting of FUO/FUI (21).

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the

performance and benefit of 18FDG PET/CT in patients who

presented with FUO at a tertiary academic general hospital in

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Patients and methods

Study population

The study was approved by the King Faisal Hospital

and Research Center (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) Institutional review

board on 11/01/2021 (approval no. 2211019), and the requirement for

informed consent was waived for the present retrospective study. A

total of 105 patients {61 men and 44 women; median [interquartile

range (IQR)] of age, 51 (31-65) years} who underwent

18FDG PET/CT because of FUO between January 2016 and

December 2019 were included in the present retrospective study.

These patients met the definition criteria of FUO (febrile illness

of >38.3˚C and no diagnosis after at least 3 days of inpatient

or 3 weeks of outpatient investigation after thorough history

taking, physical examination and standard diagnostic workup).

Eligible patients were identified in the radiology information

system by searching various categories, including FUO, IUO,

unexplained fever and fever of unknown cause. Patients with

nosocomial infection, known HIV infection, immunocompromised status

and established etiology of FUO/IUO on conventional imaging were

excluded from the present study.

Whole-body 18FDG PET/CT was requested to

determine the cause of fever. 18FDG PET/CT was performed

according to the standard protocol. The patients underwent imaging

from the vertex of the skull to the mid-thigh area. Non-contrast CT

images were used for attenuation correction and for anatomic

localization. Any 18FDG accumulation that could not be

explained by physiologic distribution was designated abnormal. Both

normal and abnormal 18FDG results were evaluated for

their diagnostic contribution to patient assessment. The

18FDG PET/CT results were classified into four

categories: i) True-positive if 18FDG PET/CT identified

the specific etiology of FUO that was confirmed with additional

investigation or response to treatment; ii) false-negative if

18FDG uptake was normal but a specific disease was

identified by another diagnostic test or response to treatment;

iii) false-positive if 18FDG uptake could not identify

the cause of FUO; and iv) true-negative if neither 18FDG

PET/CT nor standard diagnostic procedures found the cause of FUO.

The nuclear medicine physicians reading the 18FDG PET/CT

scans had knowledge of the clinical history and results of prior

imaging studies of each patient.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as the mean ±

SD for normally distributed numerical variables and as the median

[interquartile range (IQR)] for non-normally distributed numerical

variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality.

Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables.

Comparison of the groups was performed using one-way analysis of

variance for normally distributed numerical variables and the

Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed numerical

variables. Bonferroni correction was used as the post-hoc test. The

χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables. IBM

SPSS statistics software (version 26; IBM Corp.) was used for the

analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 105 patients were included (61 men and 44

women), and the median (IQR) age was 51 (31-65) years. The mean ±

SD ESR level was 71.5±40.6 mm/h. Additional acute-phase parameters

were as follows: CRP, 139 (51-234) mg/l; white blood cell count

(WBC), 8.9x103/µl (4.5-1,2103/µl); LDH, 249

U/l; and ferritin, 672 (363-1,266) µg/l A total of 21 patients

received corticosteroids before their 18FDG PET/CT

scans, 17 patients (16%) had positive blood cultures and 13

patients (12.4%) had positive urine cultures. Tissue biopsy was

performed for 46 patients (34.3%). Blood cultures, urine cultures

and tissue biopsy were performed according to standard procedures.

Table I shows the patient

characteristics.

| Table IPatient demographics, laboratory data

and PET/CT results for the total study population (n=105). |

Table I

Patient demographics, laboratory data

and PET/CT results for the total study population (n=105).

| Characteristic

(normal ranges) | Value |

|---|

| Age, years | 51 (31-65) |

| Sex | |

|

Male | 61 (58.1) |

|

Female | 44 (41.9) |

| Laboratory

data | |

|

WBC,

x103/µl (4.5-11.0) | 8.9 (4.5-12) |

|

CRP, mg/l

(8-10) | 139 (51-234) |

|

ESR, mm/h

(<15) | 71.5±40.6 |

|

LDH, U/l

(140-280) | 249 (184-444) |

|

Ferritin,

µg/l (24-336) | 672

(363-1,266) |

|

Positive

blood culture | 17 (16.2) |

|

Positive

urine culture | 13 (12.4) |

| Biopsy

performed | 36 (34.3) |

| Patients treated

with corticosteroids | 21(20) |

| PET/CT results | |

|

True-positive | 51 (48.6) |

|

False-positive | 24 (22.9) |

|

True-negative | 10 (9.5) |

|

False-negative | 20(19) |

Positive and negative 18FDG

PET/CT and classification of 18FDG PET/CT results by

final diagnosis

Of the 105 patients, 75 patients (72%) had positive

PET/CT results and 30 patients (29%) had negative results. The CRP

and ferritin values differed significantly between the two groups.

The median CRP and ferritin levels were higher in the positive

group than in the negative PET/CT group (P=0.019 and P=0.024

respectively; Table II). According

to the final diagnoses, 18FDG PET/CT results were

classified into four categories: Group 1, patients with

true-positive results (n=51; 49%), in whom abnormal

18FDG uptake identified the process that directly led to

the final diagnosis; group 2, patients with false-positive results

(n=24; 23%), in whom 18FDG uptake was not consistent

with the final diagnosis reflecting the etiology of FUO; group 3,

patients with true-negative results (n=10; 9.5%), in whom

18FDG uptake was unremarkable and no final disease was

established through follow-up or other diagnostic tests; and group

4, patients with false-negative results (n=20; 19%), in whom

18FDG PET/CT uptake was normal and final disease was

established with other tests or response to treatment. Patients in

group 1 (true-positive) were heterogeneous and no single gold

standard test was used to establish a final diagnosis. The final

diagnosis was made by the referring physician and supported by

other diagnostic studies, tissue biopsy, other laboratory tests and

continued follow-up. There were no statistically significant

differences among the four groups in terms of age, sex, WBC, ESR,

LDH or ferritin values.

| Table IIPatient characteristics based on

positron emission tomography/CT results in the total study

population (n=105). |

Table II

Patient characteristics based on

positron emission tomography/CT results in the total study

population (n=105).

| Characteristic | Group 1,

true-positive (n=51) | Group 2,

false-positive (n=24) | Group 3,

true-negative (n=10) | Group 4,

false-negative (n=20) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 52 (38-66) | 36 (23.5-65) | 56 (29-72) | 54.5 (30-64.5) | 0.564 |

| Sex | | | | | 0.980 |

|

Male | 30 (58.8) | 13 (54.2) | 6(60) | 12(60) | |

|

Female | 21 (41.2) | 11 (45.8) | 4(40) | 8(40) | |

| WBC,

103/µl | 8 (3.25-12) | 10.1

(5.92-15.145) | 8.9 (5.5-10.3) | 9.5

(4.43-11.5) | 0.595 |

| CRP, mg/l | 146.5 (70-230) | 171 (75-280) | 105 (7.4-154) | 53 (11-234) | 0.120 |

| ESR, mm/h | 154.2±100.6 | 190.4±170.3 | 107.9±106.5 | 115.8±124.9 | 0.179 |

| LDH, U/l | 244 (180-631) | 267.5

(189.5-442) | 263.5

(183-301) | 223.5

(176-305.5) | 0.705 |

| Ferritin, µg/l | 765 (452-1384) | 606.5

(352-1785.5) | 509 (342-782) | 371

(149.5-1061) | 0.135 |

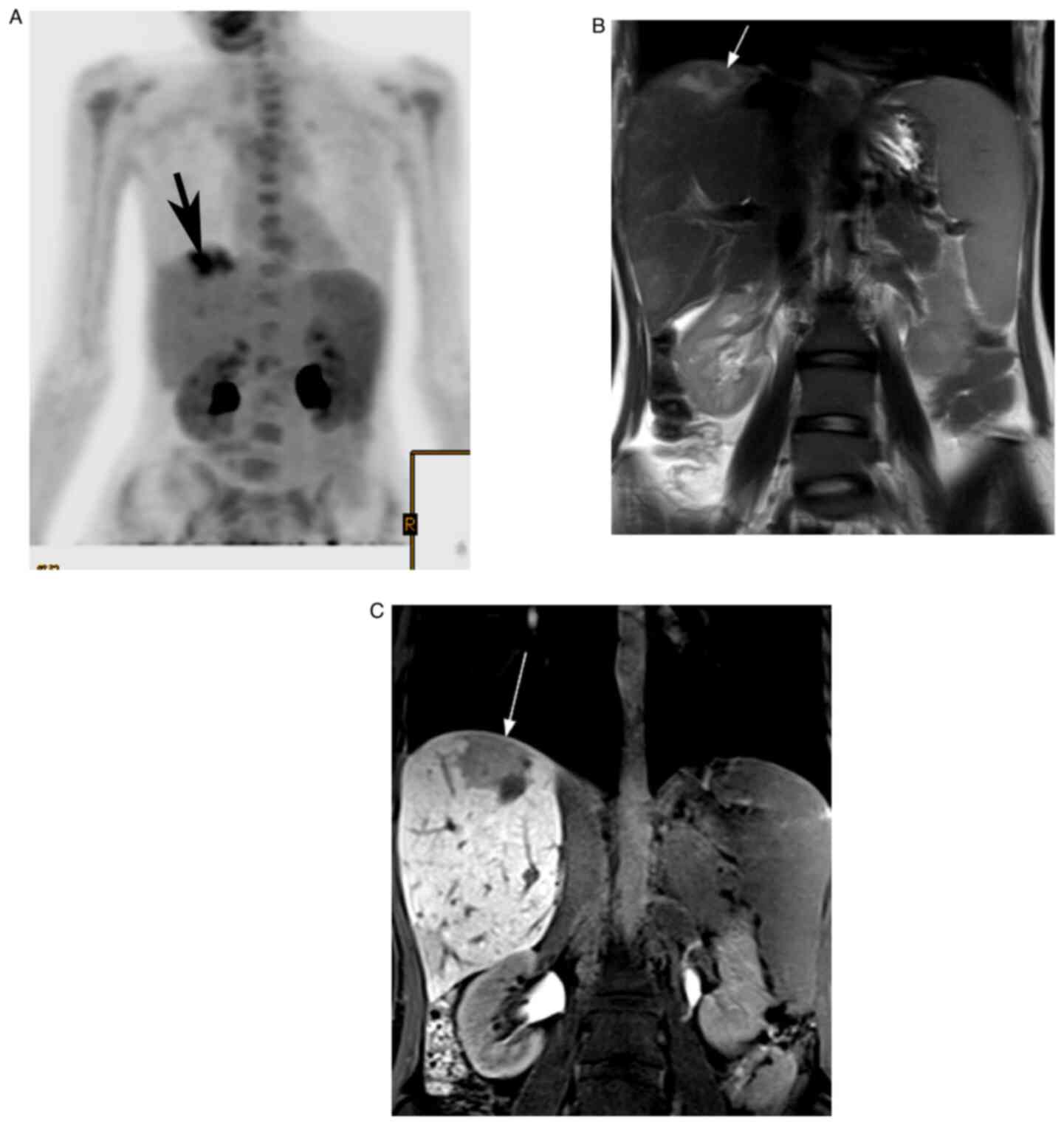

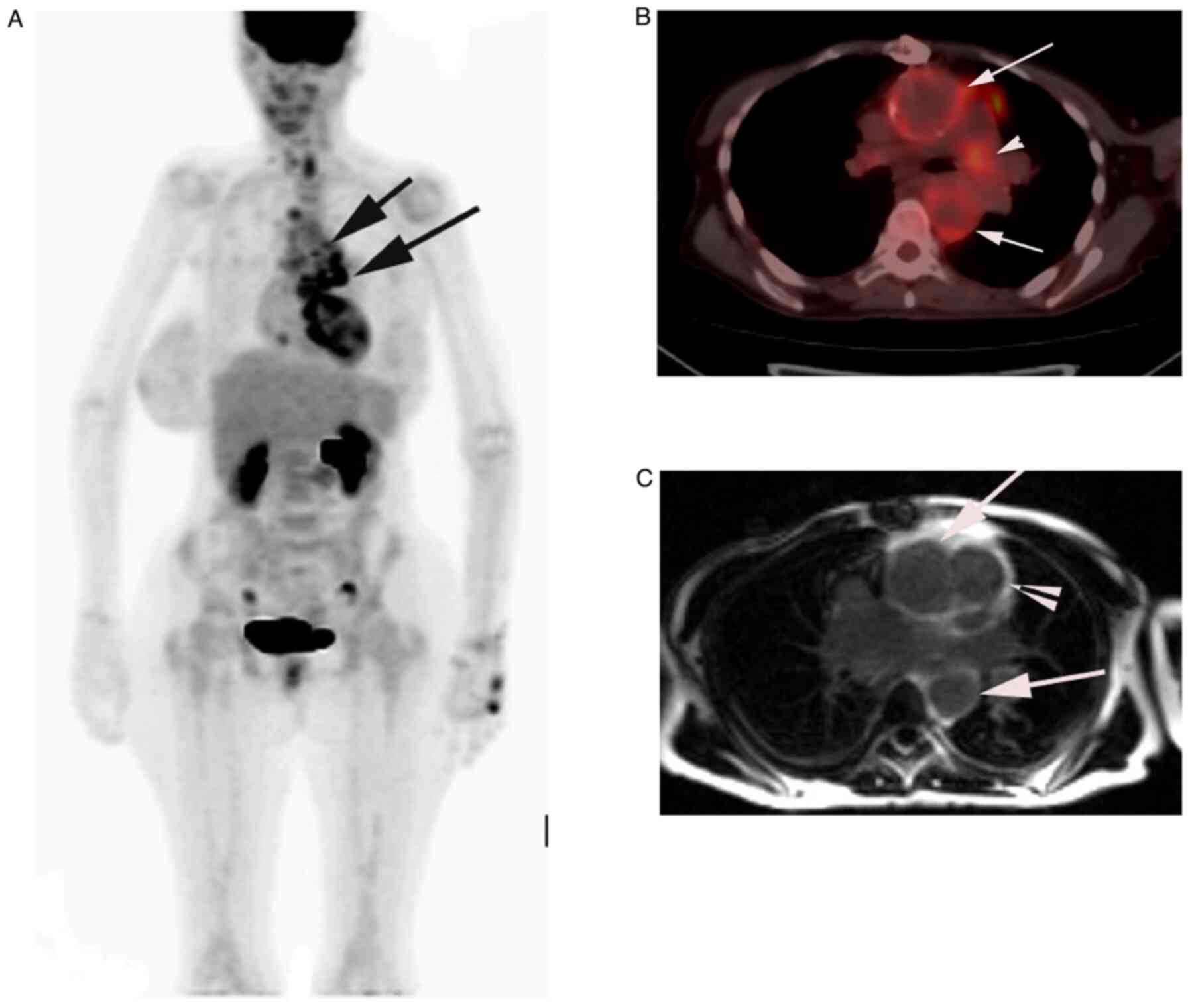

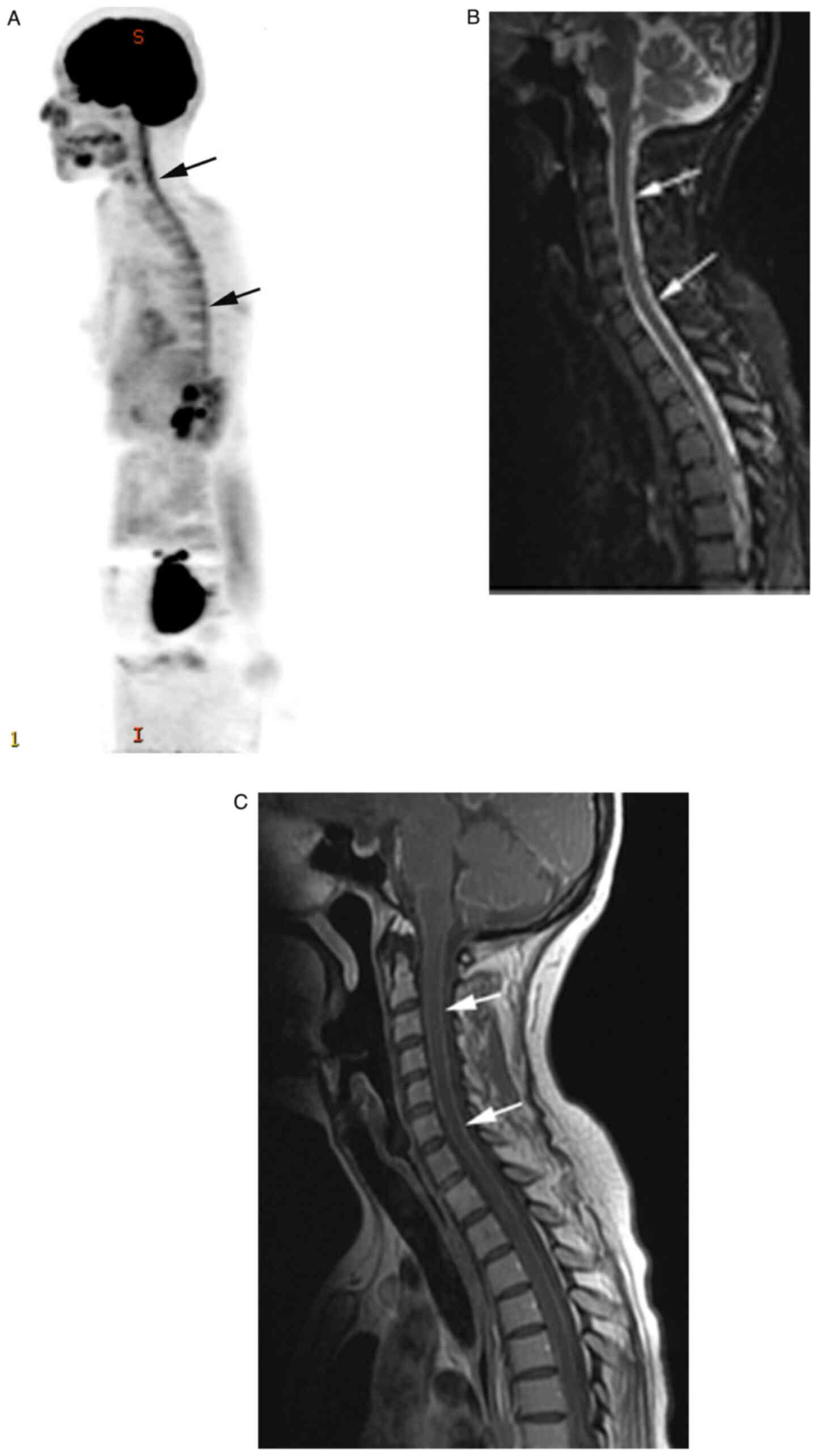

True-positive results

As shown in Table

III, of the 51 patients with true-positive PET/CT results, 26

had infections (51%), 18 (35%) had malignancies and 7 (14%) had

inflammatory noninfectious processes. For these patients, the

different disease categories, infections, neoplasms and

noninfectious inflammatory processes were compared. Examples of

cases with true-positive PET/CT scans are shown in Fig. 1, Fig.

2 and Fig. 3. The WBC and

ferritin levels differed significantly among groups (group with

infection, malignancies and inflammatory non-infectious). The WBC

count was highest in patients with infections, i.e. 11.2 (6-13.9)

103/µl compared to patients with neoplasms [3.5

(2-8.12)x103/µl] and patients with

inflammatory/autoimmune disease [8.4 (8-11.52) 103/µl]

(P=0.018). Also, the ferritin levels were significantly different

among the three true-positive groups, including infection, neoplasm

and inflammatory/autoimmune disease (P=0.04).

| Table IIIPatient characteristics and

laboratory test results in true-positive patients (n=51). |

Table III

Patient characteristics and

laboratory test results in true-positive patients (n=51).

| Characteristic | Infection

(n=26) | Neoplasm

(n=18) |

Inflammation/autoimmune (n=7) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 53±21.2 | 47.9±20.3 | 51.4±11 | 0.707 |

| Sex | | | | 0.737 |

|

Male | 14 (53.8) | 11 (61.1) | 5 (71.4) | |

|

Female | 12 (46.2) | 7 (38.9) | 2 (28.6) | |

| WBC,

103/µl | 11.2 (613.9) | 3.5 (28.12) | 8.4 (811.52) | 0.018 |

| CRP, mg/l | 11.5 (55167) | 19.0 (103 270) | 14.4 (54181) | 0.166 |

| ESR, mm/h | 78.3±33.6 | 84.3±32.9 | 96.3±44.9 | 0.477 |

| LDH, U/l | 236.5 (194438) | 346 (216826) | 162 (1211631) | 0.128 |

| Ferritin, µg/l | 714.5 (45 886) | 1115.5

(6713068) | 562 (3771451) | 0.043 |

False-positive results

In addition to the normal physiological distribution

of 18FDG, abnormal 18FDG uptake was reported

in 24 patients (23%), in whom no cause of FUO could be identified.

These results were considered false-positives. The most common

sites of abnormal 18FDG uptake were the multiple lymph

nodes above and below the diaphragm, the bone marrow, the pelvic

and bowl (including focal or diffuse uptake), the head and neck,

and the lung (areas of mediastinal and hilar adenopathy) (data not

shown).

True-negative and false-negative

18FDG PET/CT results

The 18FDG PET/CT showed a normal tracer

distribution and was reported as normal in 10 patients (9.5%), and

no final diagnosis was established. These results were considered

true negatives. False-negative PET/CT results were reported in 20

patients (19%), in whom 18FDG PET/CT was reportedly

normal, but a final diagnosis of infection (such as tuberculosis,

brucellosis or enteric fever), malignancy (such as lymphoma) or

inflammatory noninfectious disease (such as rheumatoid arthritis or

adult-onset Still’s disease) was established by other diagnostic or

laboratory tests, or after a specific therapy (data not shown).

Sensitivity, specificity and positive-

and negative-predictive values of PET/CT

The overall sensitivity, specificity, positive

predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy was 72,

29, 68, 33 and 58%, respectively (Table IV). However, due to the small

number of patients in each group, no additional analysis of the

diagnostic performance of 18FDG PET/CT was

undertaken.

| Table IVSensitivity, specificity, and

positive and negative predictive value of fluorodeoxyglucose

positron emission tomography/CT. |

Table IV

Sensitivity, specificity, and

positive and negative predictive value of fluorodeoxyglucose

positron emission tomography/CT.

| Diagnostic

performance | Value, % | 95% CI, % |

|---|

| Sensitivity | 71.83 | 59.90-81.87 |

| Specificity | 29.41 | 15.10-47.48 |

| Positive predictive

value | 68.00 | 62.07-73.40 |

| Negative predictive

value | 33.33 | 20.87-48.66 |

| Accuracy | 58.10 | 48.07-67.66 |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was

the first study in Saudi Arabia and the Middle East to investigate

the diagnostic value of 18FDG PET/CT in identifying the

underlying etiology of patients with disease with FUO. The present

study investigated 105 patients with FUO and IUO, and revealed that

18FDG PET/CT helped identify the etiology of the

underlying disease and establish a final diagnosis in 49% of

patients. This group was classified as the true-positive group,

yielding a sensitivity of 72% and a positive predictive value of

68%. PET/CT was negative in 10% of patients, in whom there was no

final diagnosis and PET/CT was considered a true negative, yielding

a low specificity and negative predictive value of 29 and 33%,

respectively. The final diagnoses of FUO etiology in this cohort

included focal or systemic infections (51%), malignancies (35%) and

inflammatory noninfectious processes (14%). These results are

comparable to those of published studies of FUO, in which the

sensitivity varied between 26 and 75% (22-31).

Determining the diagnostic value and accuracy of 18FDG

PET/CT in the setting of FUO is complex and at times controversial.

The sensitivity and specificity of 18FDG PET/CT are

difficult to establish in FUO because of the numerous potential

differential diagnoses. The most common malignancy identified in

the present cohort was lymphoma and leukemia, and other few

miscellaneous malignancy as outlined in Table SI. Gafter-Gvili et al

(13) reported 14 cases of

malignancy out of a total of 84 positive on FDG PET/CT (14%); of

them, nine were non-Hodgkin's, two were Hodgkin's lymphoma, two

were lung cancer and one was a sarcoma. In the present population,

the prevalence of infectious disease was 51%, which is relatively

higher than that in previous studies (32-34).

According to several studies on FUO, the disease-associated FUO

differs between developed countries and other countries. The

percentages of classification of FUO were 19, 24, 12, 8 and 38% for

infection, non-infection inflammatory, cancer, various etiologies

and unknown, respectively in the developed countries, in contrast

to 43, 20, 14, 7 and 16%, respectively, in developing countries

(35). The main difference in cases

of FUO between developed countries and developing countries is the

high incidence of infectious disease; for instance, infectious

disease was the most common cause of FUO in Iran (14) and Pakistan, in particular

tuberculosis (15). The usefulness

of PET/CT in the diagnostic process of FUO is also debatable. It is

unknown whether only the true-positive findings can guide the final

diagnosis or whether true-negative PET/CT results may rule out

infection, inflammation or malignancies (36).

In contrast to a previous study, in which age >50

years, CRP level >30 mg/l and absence of fever were predictive

of true-positive 18FDG PET/CT results (37), the present study revealed no

statistically significant association between PET/CT results and

age, sex, WBC, CRP, ESR, LDH or ferritin levels among different

diagnostic groups. This lack of association may be due to the wide

variety of disease distribution and prevalence in FUO. In a

previous study of more specific inflammatory diseases, such as

rheumatoid arthritis, an association existed between CRP levels and

18FDG uptake (38). When

searching for clinical and laboratory tests associated with

true-positive PET/CT results, elevated WBC counts and elevated

serum levels of ferritin were associated with infection (P=0.018

and P=0.034, respectively) in the present study. Conversely, a

previous study revealed no significant association between WBC

values and 18FDG PET/CT scan results, the clinical

impact of 18FDG PET/CT or the provision of additional

information. Other studies showed that anemia, lymphadenopathy and

male sex correlated with diagnostic 18FGD PET/CT results

(13,23).

A significant number of false-positive results were

reported in the present patients (23%), which reduced the positive

predictive value to 68% and the overall diagnostic value in the

study to 58%. This observation was most likely related to the

normal physiological distribution of 18FDG (in the

kidney, urinary bladder, and small and large intestines). The

discrimination between pathological and normal physiological uptake

in such organs is difficult, which may explain the relatively high

number of false-positives in the present study. In addition,

18FDG uptake in the bone marrow and lymph nodes may be

remarkable. Some investigators have suggested reclassifying

18FDG uptake in the setting of FUO as a nonspecific sign

of inflammation and considering the scan in such cases a true

negative. This reclassification could greatly improve the positive

predictive value and accuracy (39). Several issues may cause

false-negative findings as well. For instance, small structures are

not readily identified with PET/CT, as these small structures (such

as temporal arteries) are beyond the resolution of PET/CT. The

detection limit is ~10 mm. Furthermore, certain cancer types, such

as prostate carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma, are not very

FDG-avid (40).

Multiple previous studies have reported the value of

18FDG PET/CT. However, comparing these studies is

difficult, since the majority of these studies (including the

present study) were retrospective with different inclusion and

exclusion criteria with a possibility of selection bias. In

addition, patients who undergo normal conventional imaging are more

likely to have PET/CT scans than patients with positive

conventional imaging results. In addition, certain studies included

immunocompromised patients and comparing these patients with

non-immunocompromised patients is difficult (41). Furthermore, in most studies, the

definition of FUO was unspecified (42,43).

One meta-analysis determined that only a true-positive scan is

helpful in diagnoses (44). In the

present study, 51 patients (49%) had true-positive scans. However,

this diagnostic approach has been questioned in a more recent

meta-analysis, which suggested that true-negative scans must also

be considered helpful, since patients with true-negative scans tend

to have favorable prognoses and high spontaneous remission rates

(45). Large, prospective,

multicenter studies are needed to better investigate the role and

value of 18FDG PET/CT in patients with FUO.

The present study has certain important strengths

and limitations. The study was a retrospective, small,

single-tertiary care center study, and thus, the possibility of

referral bias cannot be excluded. There was no structured protocol

for a work-up of FUO. Both the diagnostic workup before

18FDG PET/CT and the timing of the scan itself were

performed according to the preference of the referring physicians.

The significant variations among patients may have affected the

disease prevalence and diagnostic accuracy of the test, which is

one limitation of the study; the specificity was relatively low,

only 29%, most likely due to heterogeneity of the population of the

present study. The gold standard approach for patients with FUO/IUO

is not well defined because of different patient populations among

studies and the wide variety of etiologies. Finally, another

limitation is that the cost of FDG PET/CT is relatively high and

there is limited availability.

In conclusion, the present findings demonstrated

that 18FDG PET/CT substantially contributed to the

establishment of a final diagnosis of FUO in a high percentage of

patients (72%). 18FDG PET/CT can detect metabolically

active foci that may indicate infection, malignancies and

inflammatory noninfectious processes, all of which may be the

underlying etiology of the fever. PET/CT may be helpful by

eliminating additional examinations that rule out focal processes;

however, identifying focal 18FDG activity may indicate

false-positive findings and initiate additional examinations. Based

on the present results and previous studies, it appears that

18FDG PET/CT scans have a potential role in the initial

diagnostic workup for investigation of the etiology of FUO.

However, larger, prospective, multicenter studies with more

specific referral criteria are warranted to better investigate the

role and cost-effectiveness of 18FDG PET/CT scans in the

management of FUO.

Supplementary Material

Final diagnosis based on PET/CT

findings (true-positive group).

Acknowledgements

Part of this work was presented as an oral abstract

presentation (abstract no. RPS 2606-6) at the European Congress of

Radiology (July 13-July 17), Vienna, Austria on 17. July 2022.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AF conceived the study, wrote the draft, prepared

the figures and tables, and reviewed and edited the final

manuscript. RB collected and analyzed data and prepared the draft

of the manuscript. AF and RB confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. AA analyzed data and wrote, reviewed and edited the final

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures were performed in line with the

ethical standards of the institutional research committee and

conform to the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments

or comparable ethical standards. The study was conducted at the

King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (Riyadh, Saudi

Arabia) after obtaining ethical approval from the Institutional

Review Board on 11/01/2021 (approval reference no. 2211019). The

consent to participate was waived by the ethics committee.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gaeta GB, Fusco FM and Nardiello S: Fever

of unknown origin: A systematic review of the literature for

1995-2004. Nuc Med Commun. 27:205–211. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Knockaert DC, Vanderschueren S and

Blockmans D: Fever of unknown origin in adults: 40 Years on. J

Intern Med. 253:263–275. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Bleeker-Rovers CP, Vos FJ, de Kleijn EMHA,

Mudde AH, Dofferhoff TS, Richter C, Smilde TJ, Krabbe PFM, Oyen WJG

and van der Meer JWM: A prospective multicenter study on fever of

unknown origin: The yield of a structured diagnostic protocol.

Medicine (Baltimore). 86:26–38. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

de Kleijn EM, van Lier HJ and van der Meer

JW: Fever of unknown origin (FUO). II. Diagnostic procedures in a

prospective multicenter study of 167 patients. The Netherlands FUO

study group. Medicine (Baltimore). 76:401–414. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Vanderschueren S, Knockaert D,

Adriaenssens T, Demey W, Durnez A, Blockmans D and Bobbaers H: From

prolonged febrile illness to fever of unknown origin: The challenge

continues. Arch Intern Med. 163:1033–1041. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Vanderschueren S, Del Biondo E, Ruttens D,

Van Boxelaer I, Wauters E and Knockaert DD: Inflammation of unknown

origin versus fever of unknown origin: Two of a kind. Eur Intern

Med. 20:415–418. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mansueto P, Di Lorenzo G, Rizzo M, Di Rosa

S, Vitale G, Rini G, Mansueto S and Affronti M: Fever of unknown

origin in a Mediterranean survey from a division of internal

medicine: Report of 91 cases during a 12-year-period (1991-2002).

Intern Emerg Med. 3:219–225. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Jaruskova M and Belohlavek O: Role of

FDG-PET and PET/CT in the diagnosis of prolonged febrile states.

Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 33:913–918. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Mourad O, Palda V and Detsky AS: A

comprehensive evidence-based approach to fever of unknown origin.

Arch Intern Med. 163:545–551. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Dong MJ, Zhao K, Liu ZF, Wang GL, Yang SY

and Zhou GJ: A meta-analysis of the value of

fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/PET-CT in the evaluation of fever of unknown

origin. Euro J Rad. 80:834–844. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Meller J, Sahlmann CO and Scheel AK:

18F-FDG PET and PET/CT in fever of unknown origin. J Nuc Med.

48:35–45. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Buch-Olsen KM, Andersen RV, Hess S, Braad

PE and Schifter S: 18F-FDG-PET/CT in fever of unknown origin:

Clinical value. Nuc Med Commun. 35:955–960. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Gafter-Gvili A, Raibman S, Grossman A,

Avni T, Paul M, Leibovici L, Tadmor B, Groshar D and Bernstine H:

[18F]FDG-PET/CT for the diagnosis of patients with fever of unknown

origin. QJM. 108:289–298. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Alavi SM, Nadimi M and Zamani GA: Changing

pattern of infectious etiology of fever of unknown origin (FUO) in

adult patients in Ahvaz, Iran. Caspian J Intern Med. 4:722–726.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mahmood K, Akhtar T, Naeem M, Talib A,

Haider I and Siraj-Us-Salikeen : Fever of unknown origin at a

teritiary care teaching hospital in Pakistan. Southeast Asian J

Trop Med Public Health. 44:503–511. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Takeuchi M, Nihashi T, Gafter-Gvili A,

García-Gómez FJ, Andres E, Blockmans D, Iwata M and Terasawa T:

Association of 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT results with spontaneous

remission in classic fever of unknown origin: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 97(e12909)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wright WF, Kandiah S, Brady R, Shulkin BL,

Palestro CJ and Jain SK: Nuclear medicine imaging tools in fever of

unknown origin: Time for a revisit and appropriate use criteria.

Clin Infect Dis. 78:1148–1153. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Buchrits S, Gafter-Gvili A, Eynath Y,

Bernstine H, Guz D and Avni T: The yield of F18 FDG

PET-CT for the investigation of fever of unknown origin, compared

with diagnostic CT. Euro J Intern Med. 93:50–56. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Eynath Y, Halperin E, Buchrits S,

Gafter-Gvili A, Bernstine H, Catalano O and Avni T: Predictors for

spontaneous resolution of classical FUO in patients undergoing

PET-CT. Intern Emerg Med. 18:367–374. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Chen J, Xing M, Xu D, Xie N, Zhang W, Ruan

Q and Song J: Diagnostic models for fever of unknown origin based

on 18F-FDG PET/CT: A prospective study in China. EJNMMI

Res. 12(69)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Hess S, Noriega-Álvarez E, Leccisotti L,

Treglia G, Albano D, Roivainen A, Glaudemans AWJM and Gheysens O:

EANM consensus document on the use of [18F]FDG PET/CT in

fever and inflammation of unknown origin. Eur J Nucl Med Mol

Imaging. 51:2597–2613. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Balink H, Collins J, Bruyn GA and Gemmel

F: F-18 FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of fever of unknown origin.

Clin Nucl Med. 34:862–868. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Crouzet J, Boudousq V, Lechiche C, Pouget

JP, Kotzki PO, Collombier L, Lavigne JP and Sotto A: Place of

(18)F-FDG-PET with computed tomography in the diagnostic algorithm

of patients with fever of unknown origin. Eur J Clin Microbiol

Infect Dis. 31:1727–1733. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ergül N, Halac M, Cermik TF, Ozaras R,

Sager S, Onsel C and Uslu I: The diagnostic role of FDG PET/CT in

patients with fever of unknown origin. Mol Imaging Radionucl Ther.

20:19–25. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Federici L, Blondet C, Imperiale A,

Sibilia J, Pasquali JL, Pflumio F, Goichot B, Blaison G, Weber JC,

Christmann D, et al: Value of (18)F-FDG-PET/CT in patients with

fever of unknown origin and unexplained prolonged inflammatory

syndrome: A single centre analysis experience. Inte J Clin Pract.

64:55–60. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Ferda J, Ferdová E, Záhlava J, Matejovic M

and Kreuzberg B: Fever of unknown origin: A value of

(18)F-FDG-PET/CT with integrated full diagnostic isotropic CT

imaging. Euro J Radiol. 73:518–525. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kei PL, Kok TY, Padhy AK, Ng DC and Goh

AS: [18F] FDG PET/CT in patients with fever of unknown origin: A

local experience. Nucl Med Commun. 31:788–792. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Keidar Z, Gurman-Balbir A, Gaitini D and

Israel O: Fever of unknown origin: The role of 18F-FDG PET/CT. J

Nucl Med. 49:1980–1985. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kim YJ, Kim SI, Hong KW and Kang MW:

Diagnostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with fever of

unknown origin. Intern Med J. 42:834–837. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Manohar K, Mittal BR, Jain S, Sharma A,

Kalra N, Bhattacharya A and Varma S: F-18 FDG-PET/CT in evaluation

of patients with fever of unknown origin. Jpn J Radiol. 31:320–327.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Pedersen TI, Roed C, Knudsen LS, Loft A,

Skinhoj P and Nielsen SD: Fever of unknown origin: A retrospective

study of 52 cases with evaluation of the diagnostic utility of

FDG-PET/CT. Scand J Infect Dis. 44:18–23. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

De Kleijn EM, Vandenbroucke JP and van der

Meer JW: Fever of unknown origin (FUO). I A. prospective

multicenter study of 167 patients with FUO, using fixed

epidemiologic entry criteria. The Netherlands FUO study group.

Medicine (Baltimore). 76:392–400. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Fusco FM, Pisapia R, Nardiello S, Cicala

SD, Gaeta GB and Brancaccio G: Fever of unknown origin (FUO): Which

are the factors influencing the final diagnosis? A 2005-2015

systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 19(653)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Torné Cachot J, Baucells Azcona JM, Blanch

Falp J and Camell Ilari H: Classic fever of unknown origin:

Analysis of a cohort of 87 patients according to the definition

with qualitative study criterion. Med Clin (Barc). 156:206–213.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In English,

Spanish).

|

|

35

|

Minamimoto R: Optimal use of the

FDG-PET/CT in the diagnostic process of fever of unknown origin

(FUO): A comprehensive review. Jpn J Radiol. 40:1121–1137.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Hess S: FDG-PET/CT in fever of unknown

origin, bacteremia, and febrile neutropenia. PET Clin. 15:175–185.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Schönau V, Vogel K, Englbrecht M, Wacker

J, Schmidt D, Manger B, Kuwert T and Schett G: The value of

18F-FDG-PET/CT in identifying the cause of fever of

unknown origin (FUO) and inflammation of unknown origin (IUO): Data

from a prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 77:70–77. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Kubota K, Ito K, Morooka M, Mitsumoto T,

Kurihara K, Yamashita H, Takahashi Y and Mimori A: Whole-body

FDG-PET/CT on rheumatoid arthritis of large joints. Ann Nucl Med.

23:783–791. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Kubota K, Nakamoto Y, Tamaki N, Kanegae K,

Fukuda H, Kaneda T, Kitajima K, Tateishi U, Morooka M, Ito K, et

al: FDG-PET for the diagnosis of fever of unknown origin: A

Japanese multi-center study. Ann Nucl Med. 25:355–364.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Long NM and Smith CS: Causes and imaging

features of false positives and false negatives on F-PET/CT in

oncologic imaging. Insights imaging. 2:679–698. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Pereira AMV, Husmann L, Sah BR, Battegay E

and Franzen D: Determinants of diagnostic performance of 18F-FDG

PET/CT in patients with fever of unknown origin. Nucl Med Commun.

37:57–65. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Sheng JF, Sheng ZK, Shen XM, Bi S, Li JJ,

Sheng GP, Yu HY, Huang HJ, Liu J, Xiang DR, et al: Diagnostic value

of fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission

tomography/computed tomography in patients with fever of unknown

origin. Europ J Intern Med. 22:112–116. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Kouijzer IJE, Mulders-Manders CM,

Bleeker-Rovers CP and Oyen WJG: Fever of Unknown Origin: The Value

of FDG-PET/CT. Semin in Nucl Med. 48:100–107. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Besson FL, Chaumet-Riffaud P, Playe M,

Noel N, Lambotte O, Goujard C, Prigent A and Durand E: Contribution

of (18)F-FDG PET in the diagnostic assessment of fever of unknown

origin (FUO): A stratification-based meta-analysis. Eur J Nucl Med

Mol Imaging. 43:1887–1895. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Betrains A, Moreel L, Wright WF, Blockmans

D and Vanderschueren S: Negative 18F-FDG-PET imaging in fever and

inflammation of unknown origin: now what? Intern Emerg Med.

18:1865–1869. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|