1. Introduction

Carotenoids have gained significant attention for

its potential therapeutic and preventive benefits against various

types of non-communicable diseases including diabetes, obesity,

cardiovascular disease, cancers, respiratory disorders, as well as

impaired neurodevelopment outcomes (1-6).

In preventive medicine, diet and nutrition, play a crucial role as

they are important risk factors for non-communicable diseases

(7-10).

Therefore, they should be prioritized in public health policies and

programs. Moreover, promoting healthier diets could lead to

substantial savings in health care costs and gains in

quality-adjusted life years (11,12).

Astaxanthin (AXT) is derived from various sources,

including marine organisms such as shrimp and krill, as well as

freshwater microalgae, particularly Haematococcus pluvialis

(13,14). It exhibits strong antioxidant

properties, which contribute to its anti-inflammatory,

anti-proliferative and possibly anticancer effects which are

discussed in the present review. These sources are critical not

only for their high AXT content but also for their role in

sustainable production practices, which are crucial in the current

global push for environmentally friendly and ethically sourced

supplements. In a search for more sustainable and healthy food

systems, microalga is one of the most auspicious sustainable

sources of food ingredients with a great potential in promoting

healthy diet and nutrition, thanks to the numerous pigments and

nutrients that contain, which can be used as dietary supplements

and functional foods (15-18).

In addition, microalgae are rich in bioactive

compounds with different chemical structures that can be extracted

from numerous species and can be used in the pharmaceutical field

for therapeutic purposes or to formulate drug delivery systems

(19). Nevertheless, 95% of AXT

available in the market is produced synthetically using

petrochemicals, due to cost-efficiency for mass production

(20) and the natural production is

facing challenges of a limited yield and high cost of cultivation

and extraction, both with an increasing demand for a more and more

sustainable economy, promoting biological production processes;

which until now, have been associated with very high costs

(21).

The present review, gathered and summarized the main

findings on the application of AXT in preventive and therapeutic

oncology, focusing on the hypothesized mechanisms of action

underlying its cytotoxic effects on cancer cells. It highlighted

the anti-proliferative features of AXT, particularly its ability to

induce cell death, inhibit metastasis and modulate key molecular

pathways involved in cancer progression. The present review

emphasized cancers with the most substantial body of research,

providing a clearer understanding of how AXT can be effectively

leveraged in combating these prevalent and impactful

malignancies.

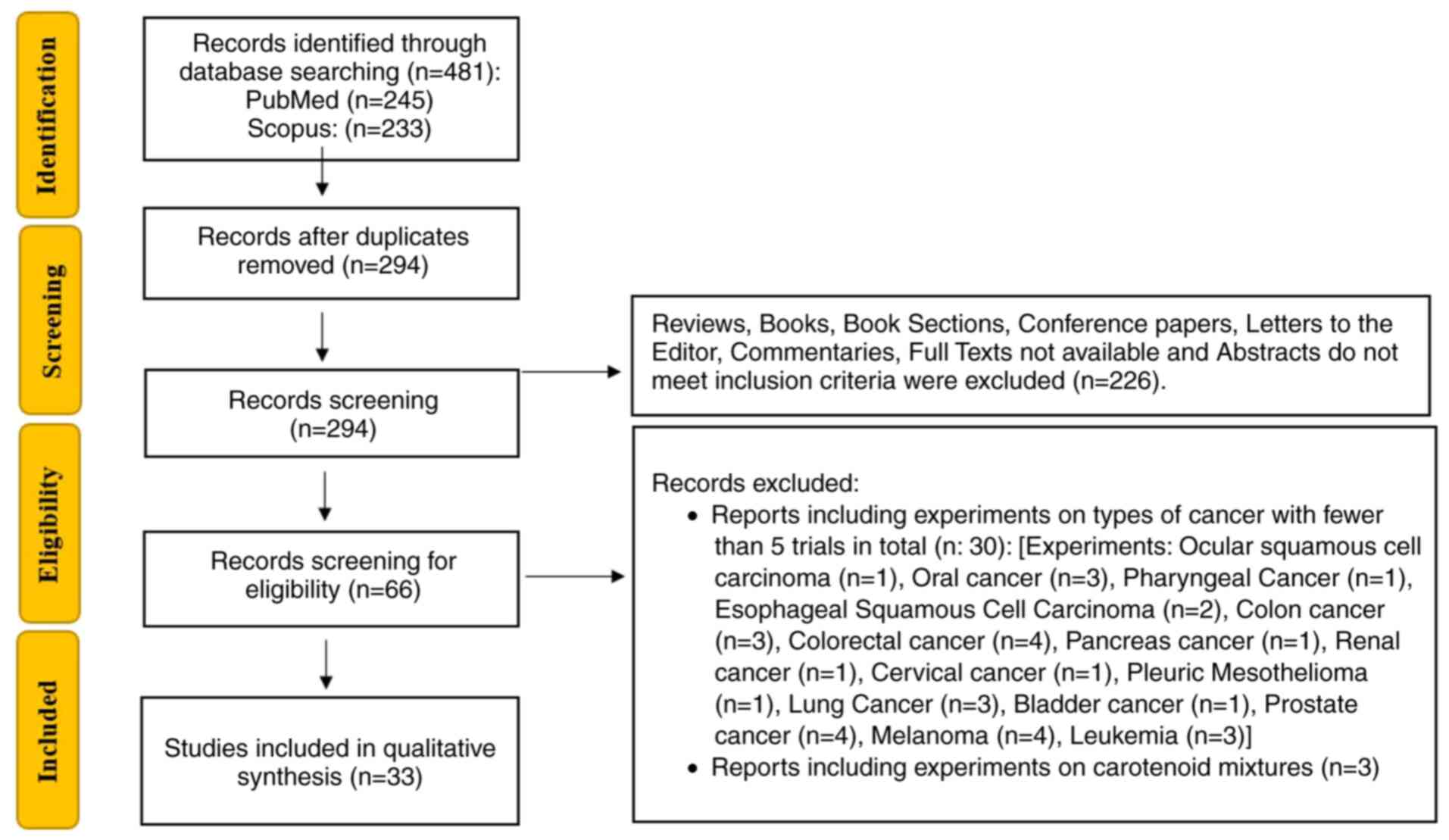

2. Protocol

A comprehensive literature search was conducted

using the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and Scopus

(https://www.scopus.com) databases, following a

clearly defined retrieval strategy. The keywords ‘Astaxanthin’,

‘Cancer’ and ‘Tumor’ were used for searches within the Title and

Abstract fields. The exact search string applied was: [Astaxanthin

(Title/Abstract)] AND [cancer (Title/Abstract)] OR [cancers

(Title/Abstract)] OR [tumor (Title/Abstract)] OR [tumors

(Title/Abstract)]. Filters were set to include only peer-reviewed

articles published from 2014 onwards. The inclusion criteria

encompassed studies published in English, conducted in vitro

or in vivo, with a minimum of five experimental articles for

each type of cancer and peer-reviewed articles providing detailed

insights into the cytotoxic mechanisms of AXT and its applications

in cancer treatment or prevention. Exclusion criteria included

articles not written in English and studies on types of cancer with

fewer than five published experiments, with the exception of

matters concerning central nervous system tumors. Additionally,

studies conducted on carotenoid mixtures containing astaxanthin

were excluded to maintain a sole focus on the specific effects of

AXT. Initial screening of titles and abstracts was performed to

assess relevance, followed by full-text reviews to confirm the

eligibility of the selected studies. Data extraction was

independently conducted by two reviewers to ensure accuracy and

consistency. The synthesized data emphasized the role of

astaxanthin in promoting cell death, inhibiting metastasis and

modulating key molecular pathways involved in cancer progression.

The flowchart summarizing the process of the present review is in

Fig. 1.

3. Astaxanthin and cancer

Nervous system tumors

AXT has been investigated for its potential in

treating some nervous system tumors, including glioblastoma

multiforme (GBM) and neuroblastoma. Furthermore, phytochemicals,

secondary metabolites in food, have been reported to protect

neuronal cells from death in neurodegenerative disorder models

through anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, opening

potential multifaceted perspectives for their application (22).

GBM is one of the most aggressive forms of primary

brain cancer, with very low survival rates and a significant impact

on the patient's quality of life. As the most prevalent primary

malignant brain tumor, glioblastoma accounts for 57% of all gliomas

and 48% of all primary malignant central nervous system tumors

(23). Patients diagnosed with

glioblastoma often experience a rapid deterioration in neurological

function, suffering from significant symptoms caused not only by

the tumor but also by the side effects of various treatments

(24).

When human GBM cell lines U251-MG and T98-MG, but

not CRT-MG and U87-MG, are pretreated with AXT their sensitivity to

tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is

significantly enhanced; thereby increasing the apoptotic response

(25). Furthermore, the combined

treatment shows improved effectiveness in inducing apoptosis

compared with AXT or TRAIL alone, especially in the more responsive

cell lines such as U251-MG and U87-MG, indicating that AXT may

sensitize tumor cells to apoptosis-inducing agents. The differing

sensitivity of these cell lines likely stems from distinct

mechanisms, such as antioxidant expression and mitochondrial

dynamics. U251-MG cells have lower Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2)

expression and enzymatic activity compared with CRT-MG.

Overexpression of SOD2 in U251-MG eliminates the AXT-induced

sensitization to TRAIL treatment, indicating that SOD2 plays a

critical role in the differential response between the two cell

lines (25). These findings

underscore that the ability of AXT to enhance cancer treatment may

depend on the genetic and metabolic profile. Additionally, AXT

exhibits hormetic effects on U251-MG, T98G and CRT-MG cell lines,

where low doses stimulate cell proliferation by upregulating

markers such as cyclin-dependent kinases, while higher doses induce

apoptosis by triggering a dose-dependent oxidative stress response,

significantly increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and

promoting apoptosis (26).

Targeting cyclin-dependent kinases with specific inhibitors could

potentially improve treatment efficacy by reducing chemoresistance

and enhancing the response to chemotherapy, as indicated also by

Patel et al (27) for

colorectal and oral cancers.

Further investigations into the effects of AXT on

glioblastoma were conducting both in vitro in U251MG and

GL261 cell lines and in vivo in C57BL/6J mice model. The

in vitro results indicate that AXT could suppress cell

viability and proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner,

reducing cell migration and influencing key signaling molecules

(ERK1/2, Akt and p38 MAPK) involved in tumor progression (28). The combined treatment of AXT with

temozolomide, a standard chemotherapy drug for glioblastoma,

enhanced the antitumor effects compared with AXT alone. In

vivo, AXT significantly suppressed glioblastoma tumor growth,

demonstrating its capacity to accumulate in brain tissue and

effectively inhibit tumor progression (28).

Neuroblastoma is a common and aggressive pediatric

cancer that originates in nerve tissues, responsible for a

significant number of childhood cancer mortalities and presenting

challenges for effective treatment due to its diverse genetic,

morphological and clinical presentations; it most often begins in

the adrenal glands but can also develop in other areas such as the

neck, chest, abdomen, or spine (29). The effects of AXT were explored on

SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cell line both in vitro and in

vivo. In vitro AXT revealed strong anti-tumor activity by

inhibiting proliferation, migration and invasion, while also

promoting apoptosis (30). When AXT

was combined with small interfering (si)RNA targeting the STAT3

signaling pathway, a synergistic effect was observed, further

enhancing the reduction of tumor cell viability and aggressive

behavior in vivo (30) The

STAT3 pathway is implicated in resistance to chemotherapy and the

ability of AXT to inhibit STAT3 could theoretically help counteract

this resistance, making it a promising candidate for further

investigation in chemoresistant cancer models.

AXT is known for being able to modulate cell

survival, redox biology and bioenergetics status by influencing key

signaling pathways (31). García

et al (32) demonstrate that

AXT reduces mitochondrial superoxide (O2-•) production in SH-SY5Y

cells exposed to N-methyl-D-aspartate. Zhang et al (33) found that AXT activates the

PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway, leading to the upregulation of nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor,

in SH-SY5Y cells under oxygen and glucose deprivation conditions.

More recently AXT was shown being able to reduces mitophagy through

the Akt/mTOR pathway, suggesting its potential in preventing

neurotoxicity in neurodegenerative diseases (34). As a matter of fact, the regulation

of mitochondrial membrane pore formation has been previously

proposed as a neuroprotective mechanism of AXT in aging and

neurodegenerative disorders and thus also explains their dual

functions in neuronal and cancer cells (22). As an antioxidant, AXT has the

potential to act as both an anticancer drug and a neuroprotectant.

In cancer, AXT limits tumor growth by modulating ROS produced under

stressful conditions in rapidly proliferating cells. Conversely,

AXT protects against oxidative stress, which causes mitochondrial

dysfunction and apoptosis, thereby reducing the detrimental effects

associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's,

Parkinson's and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (35).

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed type

of cancer in women worldwide, with higher incidence rates in high

High Development Index (HDI) countries and markedly lower in medium

and low HDI countries. Survival rates also vary markedly between

developed and less developed countries, highlighting disparities in

healthcare quality and access to healthcare (36). Research findings reveal that AXT

treatment of human breast cancer cell lines effectively reduces

cancer progression in a dose-dependent manner by inhibiting cell

growth and inducing apoptosis without affecting non-tumorigenic

cell lines. AXT alleviates inflammation and the immunosuppressive

environment within tumors, creating less favorable conditions for

cancer growth and its spread, reducing cancer cell migration and

metastasis formation (37-43).

AXT may modulate various pathways involved in the activation of

apoptosis, targeting key signaling pathways critical in breast

cancer progression, including angiogenesis, cellular stress

response, lipid metabolism and the regulation of inflammation

(40,41,44).

In vitro, AXT significantly reduces cell

proliferation and migration in both the MCF7 (ER-positive) and

MDA-MB-231 (triple-negative) breast cancer cell lines in a

dose-dependent manner. However, the MDA-MB-231 cell line was more

sensitive to the anti-migratory effects of AXT due to its higher

metastatic potential and apoptotic gene expression was also more

prominently observed in these cells (45). In SKBR3 cells, AXT decreased the

expression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) and

other related oncogenic proteins that are typically overexpressed

in SKBR3 cells (40). This

downregulation of HER2 and associated signaling pathways indicates

that AXT may interfere with survival and proliferation signals in

HER2-positive breast cancer cells. Astaxanthin treatment also

significantly reduces the expression of pontin in T47D and BT20

cell lines (37) and mutant p53

(mutp53) in T47D, BT20 and SKBR3 cell lines (37,40).

Notably, the knockdown of pontin through siRNA mirrors the effect

of AXT on gene expression and markedly reduces the proliferation,

migration and invasion of cancer cells. Therefore, by lowering both

pontin levels and ROS, AXT also reduces mutp53. Sowmya et al

(46) studied the effects of AXT

derived from shrimp, alone and combined with β-carotene and lutein

from greens, on MCF-7 breast cancer cells. This combination

exhibits enhanced cytotoxicity and oxidative stress compared with

individual treatments or saponified shrimp carotenoid extract. This

combination selectively killed MCF-7 cancer cells by modulating key

proteins involved in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis leading to

cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase, with no

adverse effects on normal breast epithelial cells (MCF-10A).

In vivo, Yuri et al (47) examined dietary AXT effects on

mammary carcinogenesis in female Sprague-Dawley rats treated with

N-methyl-N-nitrosourea; higher concentrations of AXT significantly

reduces the incidence of palpable mammary tumors compared with the

control group. AXT's anticarcinogenic effects are also associated

with decreased adiponectin expression in mammary adipose tissues,

which is linked with anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor properties

and its upregulation may help reduce tumor progression (47). Furthermore, a protective effect on

tissue is shown by histological analysis, indicating that AXT

preserves tissue integrity in mammary glands, exerting a protective

role against cellular damage caused by carcinogens (47).

Combined treatments were tested to enhance the

efficacy of cell death induction in breast cancer cells. The

synergistic cytotoxic effect of AXT with melatonin showed enhanced

efficacy in the T47D cell line compared with the MDA-MB-231 line

(39). The increased effectiveness

in T47D cells is attributed to its triple-positive receptor status

(expressing estrogen, progesterone and HER2 receptors), which may

increase the sensitivity of these cells to apoptosis-inducing

effects. By contrast, MDA-MB-231, being a triple-negative breast

cancer line, exhibited lower sensitivity to the combined treatment.

This variability suggested that receptor status and genetic

differences between cell lines play a significant role in the

differential response to astaxanthin and melatonin (39). Fouad et al (48) investigated the combined effects of

eugenol (EUG) and AXT with doxorubicin (DOX) on MCF7 cells, a

hormone receptor-positive breast cancer cell line. Key findings

showed that EUG and AXT markedly increased the cytotoxic effect of

DOX on MCF7 cells through epigenetic modifications and immune

modulation. Notably the EUG and AXT combination increased histone

acetylation and histone acetyltransferase expression and decreased

aromatase and EGFR expression which is critical in breast cancer

cell proliferation and survival. Vijay et al (44) studied the combined effects of AXT

and other carotenoids with low doses of DOX on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

breast cancer cells; combining carotenoids with a minimal cytotoxic

dose of DOX resulted in greater cytotoxic effects, more

significantly in MCF-7 cells, than either higher doses of DOX alone

or carotenoids alone through the modulation of redox balance. This

combination not only promoted apoptosis and arrested the cell cycle

in the G0/G1 phase but also exhibited minimal cytotoxicity in

normal breast epithelial cells (MCF 10A). Atalay et al

(49) focused on the effects of AXT

combined with carbendazim on MCF-7 breast cancer cells; this

combination significantly increased the anti-proliferative effects

compared with carbendazim and AXT alone and increased cell cycle

arrest in the G2/M phase. Furthermore, co-treatment with

AXT reduced the elevated ROS levels induced by carbendazim,

potentially lessening oxidative stress-related side effects while

maintaining the anti-cancer efficacy, suggesting that combining ATX

with carbendazim could enhance anti-cancer effects while mitigating

some of the oxidative stress typically induced by chemotherapy

agents (49). Malhão et al

(45) investigated the effects of

AXT on breast cancer cells, both as a standalone treatment and in

combination with conventional chemotherapy drugs (cisplatin and

DOX). AXT alone did not show significant cytotoxic effects on the

cancer cell lines tested, including luminal MCF7 SKBR3 (HER-2

positive) and MDA-MB-231 (triple-negative), as well as a

non-tumoral breast cell line, MCF12A. However, in combination with

cisplatin or DOX, the effect of AXT is varied. In some instances,

it reduces the cytotoxicity of cisplatin, particularly with

cisplatin on the SKBR3 breast cancer cell line, indicating a

potential protective effect. In certain cases, AXT enhances the

cytotoxic effect of the chemotherapy drugs, specifically when

combined with DOX on the MCF7 cell line. The results suggest that

while AXT itself does not directly induce strong cytotoxic effects

against breast cancer cells, its interactions with chemotherapy

drugs can influence treatment outcomes, though not always in a

favorable way. This highlights the need for further research to

improve understanding of the role of AXT in combination

therapies.

Research also shows promising potential for using

functionalized nanoparticles in breast cancer therapy. A

nanoparticle formulation combining DOX with low-molecular-weight

heparin (LMWH) and AXT, known as LMWH-AST/DOX nanoparticle (LA/DOX

NP), has been studied. The findings highlight that LA/DOX NPs

effectively suppressed liver metastasis by inhibiting the formation

of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (41). Furthermore, ATX-reduced gold

nanoparticles (ATX-AuNPs) were studied in MDA-MB-231 human breast

cancer cells, showing dose-dependent cytotoxic effects and

significant antiproliferative activity, indicating potent efficacy

in inhibiting cell growth. The results illustrate that ATX-AuNPs

exhibit enhanced cytotoxic effects compared with free ATX alone,

indicating that these nanoparticles can induce programmed cell

death more effectively than free AXT and improved cellular uptake

(50). ATX-loaded chitosan

oligosaccharide/alginate nanoparticles (ATX-COANPs) also offer a

promising solution to the challenges of low solubility, bio

accessibility and bioavailability of ATX. By encapsulating ATX

within COANPs, the bioactive properties of astaxanthin are

enhanced, with improved in vitro anti-inflammatory activity

and significant cytotoxic effects on MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

This nanostructure, optimized using Box-Behnken design and response

surface methodology, presents an effective delivery mechanism for

ATX in nutraceutical and functional food application (51).

Gastrointestinal cancers

Gastrointestinal cancers encompass a diverse group

of malignancies affecting the digestive system, including the

esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas, gallbladder and intestines.

The incidence of gastrointestinal cancer is rising, with

age-standardized diagnosis rates showing significant global

variations, with the highest rates observed in South America,

Eastern Asia and Central and Eastern Europe (52). Due to delayed detection and the lack

of effective treatments, GC has a poor prognosis, with a number of

patients diagnosed at advanced stages and mortality often occurring

within the first year of diagnosis (53). Understanding the specific

characteristics and risk factors of each type is crucial for early

detection, effective treatment and improving patient outcomes. The

chemo preventive and cytotoxic potential of AXT has been

extensively studied in relation to oral, liver and gastric cancers,

demonstrating promising results and showcasing AXT's ability to

inhibit tumor growth and induce apoptosis in cancer cells.

Liver cancer

Liver cancer, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), is

a major cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide and its

increasing incidence, particularly in patients with cirrhosis,

poses significant treatment challenges (54). The complexity of HCC treatment

arises from the variability in tumor size, number of nodules and

patient liver function. Liver transplantation is considered the

most effective long-term treatment, but is limited by strict

eligibility criteria and organ availability (55). AXT has been extensively studied for

its potential therapeutic and preventive benefits primarily

focusing on various HCC cell lines and animal models. In

vitro and in vivo studies are mainly based on the HepG2

hepatoma cell line. By using Kunming mice, Shao et al

(56) demonstrate that AXT inhibits

the proliferation of H22 hepatoma cells in vitro and in

vivo and induces both apoptosis and necrosis as indicated by

nuclear condensation and fragmentation analysis in treated cells.

Although the apoptosis rate did not vary significantly between low-

and high-dose groups, cell necrosis increased markedly, with

high-dose AXT performing similarly to cisplatin. Additionally, AXT

effectively reduced tumor size and the number of cancer cells in

mice, supporting its potential anti-tumor activity. These findings

highlight AXT's role in inhibiting tumor growth and inducing cell

death. Zhang et al (57)

encapsulated AXT in biodegradable calcium alginate microspheres to

enhance its bioavailability and stability, protecting it from

degradation in harsh environmental conditions such as gastric

acids. This study demonstrates that AXT treatment reduces ROS

levels specifically in HepG2 cells, leading to significant

inhibition of cell growth. Notably, this cytotoxicity was

selective, sparing normal hepatocytes (THLE-2 cells), thereby

highlighting AXT's potential for targeted cancer therapy without

harming healthy cells (57). Thus,

encapsulated AXT in calcium alginate microspheres enhances

stability, enables controlled release and improves selective

cytotoxicity toward cancer cells, minimizing effects on healthy

cells. This approach reduces oxidative stress in normal cells,

improves cellular uptake in cancer cells and offers a safer, more

effective delivery method, making encapsulated AXT a promising

option for targeted cancer therapy.

Another approach involves using natural sources of

AXT, as in the study by Messina et al (58), which assesses the bioactive

properties of AXT extracted from shrimp by-products on hepatoma

cells (Hep-G2). This research shows dose-dependent

anti-proliferative effects, where increasing concentrations of AXT

decreased cell vitality and induced apoptosis, marked by the

increase in p53 protein levels and activation of caspase-3

Considering that 53 is among the most well-known tumor progression

inhibitors. it is reasonable that AXT activates apoptosis

modulating p53 expression/activity.

These markers are critical in the cellular apoptotic

pathway, reinforcing AXT's potential to induce programmed cell

death in cancer cells (58).

Further extending the scope of the effect of AXT on liver cancer,

Li et al (59) examined both

natural and synthetic forms of AXT on different human hepatoma cell

lines, LM3 and SMMC-7721. Their findings highlight that AXT

inhibits growth by downregulating critical signaling pathways such

as NF-κB p65 and Wnt/β-catenin. These pathways are instrumental in

the regulation of gene expression linked to cell proliferation and

survival. AXT stabilizes IκB-α, preventing the nuclear

translocation of NF-κB p65 and thus inhibiting this pathway and the

consequent survival of cancer cells. Additionally, AXT influences

the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, further strengthening its role in

reducing proliferation and inducing apoptosis in a dose-dependent

manner, with significant effects observed at higher concentrations

(59). The study observed that AXT

was comparably effective in both LM3 and SMMC-7721 HCC cell lines,

demonstrating dose- and time-dependent inhibition of cell

proliferation and induction of apoptosis in both of the lines

(59). The anti-proliferative

effects of carotenoid mixture extracted from microalgae

(Monoraphidium sp. and Scenedesmus obliquus),

includes AXT as a major component, was also explored using the HCC

cell line HUH7(60). The study

highlights that Monoraphidium sp., which had the highest

amounts of AXT, exhibits stronger antioxidant and

anti-proliferation activities compared with Scenedesmus

obliquus. This underscores the significance of exploring

freshwater microalgae as a source of high-yielding AXT for

pharmaceutical applications (60).

AXT's potential in combination with chemotherapy

drugs is confirmed in studies from animal studies. Ren et al

(61), in an in vivo mouse

mode, shows that combining AXT with sorafenib enhances anti-tumor

immune responses in hepatocellular carcinoma. AXT increases CD8+ T

cell infiltration, polarizes macrophages towards the M1 phenotype,

boosts anti-tumor cytokines and positively alters gut microbiota,

improving overall immune function and treatment efficacy, thus

reducing some of the systemic and gut-related side effects of

sorafenib (61). By enhancing

immune responses, AXT may overcome some of the mechanisms that

allow chemo-resistant tumors to evade treatment. Subsequently, the

same authors demonstrated in vivo that AXT combined with

sorafenib enhances tumor suppression more significantly than in

vitro, indicating that the efficacy of AXT may depend on

mechanisms beyond direct cytotoxicity observed in cell culture,

such as its role in modifying the tumor microenvironment or

impacting pathways relevant to in vivo models (62). Furthermore, the combination

treatment appeared to reduce symptoms linked to cachexia; such as

muscle wasting, which are typically observed with sorafenib alone

(62). By enhancing the

effectiveness of a lower, subclinical dose of sorafenib, AXT

potentially allows for a reduction in the standard sorafenib dose,

thereby decreasing the likelihood of its associated toxicities.

Gastric cancer

Gastric cancer is a significant global health issue,

with >1 million new cases estimated annually, making it the

fifth most diagnosed cancer worldwide. Due to often being diagnosed

at an advanced stage, gastric cancer has a high mortality rate,

ranking as the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths with

784,000 deaths reported globally in 2018(63). Helicobacter pylori is the

primary risk factor for gastric cancer, being the main cause of

chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Despite decreasing

infection rates in a number of countries due to improved living

standards, its prevalence remains high, particularly in the Far

East and is linked to socioeconomic status and hygiene levels

(64).

The effects of AXT on gastric cancer were studied

using the AGS adenocarcinoma cell line to investigate how H.

pylori infection markedly alters gene expression, upregulating

genes associated with inflammation, cell proliferation and cancer

pathways (65-67).

Kim et al (65) found that

AXT administration results in altered expression of several genes

involved in cell motility and cytoskeleton remodeling, notably

c-MET, PI3KC2, PLCγ1, Cdc42 and ROCK1, which are critical for these

processes. The role of AXT in mitigating the effects of H.

pylori infection was further studied by Lee et al

(66) on human gastric epithelial

cell line AGS. AXT effectively inhibits H. pylori-induced

apoptosis in AGS cells as demonstrated by the reduction in key cell

death markers such as DNA fragmentation, caspase-3 activity and the

cytochrome c release. Furthermore, the study indicates that,

in H. pylori-stimulated AGS cells, AXT enhances autophagy,

through increasing the phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein

kinase (AMPK) and consequently downregulating mTOR. It was also

found that pretreatment of AGS cells with AXT counteracted H.

pylori-induced changes by reducing the expression of key genes

involved in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (67). This includes the downregulation of

porcupine, Fos-like 1 and c-myc, which are associated with cancer

cell proliferation and survival (67). In addition, AXT reversed H.

pylori-induced repression of tumor suppressor genes such as

SMAD4 and BAMBI, which are involved in the regulation of cell

proliferation and survival, and reduced expression of spermine

oxidase (SMOX) involved in oxidative stress (67).

AXT effectively inhibits the expression of MMP-7 and

MMP-10 in H. pylori-infected gastric epithelial cells. These

enzymes are crucial for degrading the extracellular matrix, which

typically facilitates tumor invasion and metastasis. By reducing

the invasive and migratory capabilities of these cells, AXT limits

their ability to spread following H. pylori infection

(68). Furthermore, H.

pylori infection increases the expression of integrin α5 in AGS

cells, which in turn enhances cell adhesion and migration, key

processes in cancer metastasis. This increase is linked to elevated

ROS levels and activation of the JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway

(69). AXT effectively lowers ROS

levels in AGS cells and suppressed the activation of JAK1/STAT3.

Consequently, AXT also decreases the expression of integrin α5,

leading to reduced cell adhesion and migration in the H.

pylori-stimulated AGS cells (69).

A dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation

was also documented for a number of other adenocarcinoma cell lines

including AGS, KATO-III, MKN-45 and SNU-1. When administered to

KATO-III and SNU-1 cells, AXT has a more pronounced effect,

inhibiting cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner and

decreasing the percentage of cells in the S phase. Accordingly

p27kip-1 expression, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that

regulates the cell cycle, is increased, thereby contributing to the

observed G0/G1 arrest (70). By contrast, AXT shows minimal

effects on the viability of AGS and MKN-45 cells and did not

significantly alter cell cycle progression in these cell lines

(70). Others mechanisms explaining

the antiproliferative features of AXT in AGS cancer lines have been

reported, including the involvement of ERK and the activation of

necroptosis-related proteins such as NADPH oxidase,

receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIP) 1, RIP3 and mixed lineage

kinase domain-like protein (71).

In vivo, on male C57BL/6 mice used as animal

model, AXT was observed to reduce oxidative stress, as indicated by

decreased lipid peroxide levels and myeloperoxidase activity and

suppression of inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ, as well as oncogene

expression, such as c-myc and cyclin D1, which are associated with

cancer progression (72). The study

suggests that AXT can help to protect against oxidative damage,

inflammation and oncogene activation in gastric tissues,

potentially offering a preventive strategy against H.

pylori-associated gastric carcinogenesis.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, AXT holds considerable promise as a

bioactive compound with therapeutic and preventive potential in

cancer management. Extensive in vitro and in vivo

research underscores its efficacy across multiple cancer types,

including nervous system, breast and gastrointestinal cancers,

largely due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and

anti-proliferative properties. AXT exerts significant effects by

modulating various key molecular pathways involved in cancer

progression, cellular stress responses and neuroprotection. It has

been shown to activate the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway, leading to the

upregulation of Nrf2, a transcription factor crucial for oxidative

stress regulation. It also modulates the Akt/mTOR pathway,

influencing mitophagy and preventing excessive apoptosis, thus

exhibiting potential in reducing neurotoxicity and affecting cancer

cell behavior. It was also found to inhibit the JAK1/STAT3 pathway,

which is associated with cell adhesion and migration, particularly

in the context of cancer metastasis. Additionally, it downregulates

the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thereby reducing cancer cell

proliferation and survival. The NF-κB pathway is also affected by

AXT, as it stabilizes IκB-α to prevent the nuclear translocation of

NF-κB p65, thereby inhibiting survival signals in cancer cells.

Likewise, p53, the most well-known tumor progression inhibitor may

be influenced by AXT in several cancers preventing cancer growth

and invasiveness. By targeting cyclin-dependent kinase pathways,

AXT promotes cell cycle arrest, contributing to reduced cancer cell

proliferation.

Furthermore, AXT enhances autophagy through the

AMPK/mTOR pathway, reducing cell proliferation in cancer models.

Last, AXT affects the ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK signaling pathways, which

are involved in tumor suppression, as demonstrated in studies on

glioblastoma. These regulatory effects underscore AXT's potential

as a multifaceted agent in cancer therapy and neuroprotection,

warranting further clinical research to fully validate its

therapeutic role. The synergy observed when AXT is combined with

chemotherapeutic agents highlights its role in enhancing treatment

efficacy and minimizing adverse effects, especially in breast and

liver cancers. Moreover, innovations in AXT delivery, such as

encapsulation in nanoparticles, have further improved its

bioavailability and targeted action, enabling more effective cancer

cell targeting and potentially reducing systemic side effects.

However, despite promising laboratory results, further in

vivo studies and clinical trials are essential to validate

AXT's therapeutic effects in human populations. These studies would

allow the establishment of standardized dosing regimens, confirm

safety profiles and AXT's interactions with conventional therapies

across diverse cancer populations. It is important to note that

research on certain types of cancer remains limited. Therefore, the

conclusions drawn for these specific cancers should be interpreted

with caution, as they may not be as robust or comprehensive as

those for more extensively studied malignancies.

As a future direction, it would be valuable to

conduct comparative studies between natural and synthetic AXT to

improved understand their respective efficacies and potential

differences in biological activity. Additionally, further research

combining AXT with other bioactive compounds from natural sources

would be beneficial, as these combinations can exhibit synergistic

effects that enhance its overall therapeutic potential. This

synergy can result in superior antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and

anticancer effects compared with synthetic AXT alone. Investigating

these synergistic interactions and exploring the potential of

combining AXT with other naturally occurring compounds could pave

the way for more effective, multi-targeted cancer treatments and

preventive strategies.

Continued research into the bioavailability,

delivery mechanisms and role of AXT in combination therapies could

facilitate its incorporation into clinical oncology, potentially

offering a natural, complementary approach to current cancer

treatments.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Professor R. Villagonzalo

Rountree for his assistance with English editing.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Ministry of

University and Research (MUR) as part of the FSE REACT-EU-PON

2014-2020 Research and Innovation resources-Green/Innovation

Action-DM MUR 1062/2021-GrEEnoncoprev. The present study was also

supported by the Department of Medical, Surgical and Advanced

Technologies ‘G.F. Ingrassia’, University of Catania, Italy.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

CC and MF contributed to the study design; CF and CS

developed the methodology; CC and MFT were responsible for data

curation and original draft preparation; AG, HGD and GOC reviewed

and edited the manuscript; MF supervised the project and secured

funding for the study. Data authentication is not applicable. All

authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ahmed S, Hasan MM, Heydari M, Rauf A,

Bawazeer S, Abu-Izneid T, Rebezov M, Shariati MA, Daglia M and

Rengasamy KR: Therapeutic potentials of crocin in medication of

neurological disorders. Food Chem Toxicol.

145(111739)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Bakac ER, Percin E, Gunes-Bayir A and

Dadak A: A narrative review: The effect and importance of

carotenoids on aging and aging-related diseases. Int J Mol Sci.

24(15199)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Ferreira YAM, Jamar G, Estadella D and

Pisani LP: Role of carotenoids in adipose tissue through the

AMPK-mediated pathway. Food Funct. 14:3454–3462. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Melo van Lent D, Leermakers ETM, Darweesh

SKL, Moreira EM, Tielemans MJ, Muka T, Vitezova A, Chowdhury R,

Bramer WM, Brusselle GG, et al: The effects of lutein on

respiratory health across the life course: A systematic review.

Clin Nutr ESPEN. 13:e1–e7. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sani A, Tajik A, Seiiedi SS, Khadem R,

Tootooni H, Taherynejad M, Sabet Eqlidi N, Alavi Dana SMM and

Deravi N: A review of the anti-diabetic potential of saffron. Nutr

Metab Insights. 15(11786388221095223)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Sui J, Guo J, Pan D, Wang Y, Xu Y, Sun G

and Xia H: The efficacy of dietary intake, supplementation, and

blood concentrations of carotenoids in cancer prevention: Insights

from an umbrella meta-analysis. Foods. 13(1321)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ferrante M, Fiore M, Conti GO, Fiore V,

Grasso A, Copat C and Signorelli SS: Transition and heavy metals

compared to oxidative parameter balance in patients with deep vein

thrombosis: A case-control study. Mol Med Rep. 15:3438–3444.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Fiore M, Cristaldi A, Okatyeva V, Lo

Bianco S, Oliveri Conti G, Zuccarello P, Copat C, Caltabiano R,

Cannizzaro M and Ferrante M: Dietary habits and thyroid cancer

risk: A hospital-based case-control study in Sicily (South Italy).

Food Chem Toxicol. 146(111778)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Fiore M, Barone R, Copat C, Grasso A,

Cristaldi A, Rizzo R and Ferrante M: Metal and essential element

levels in hair and association with autism severity. J Trace Elem

Med Biol. 57(126409)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Phillips CM, Chen LW, Heude B, Bernard JY,

Harvey NC, Duijts L, Mensink-Bout SM, Polanska K, Mancano G,

Suderman M, et al: Dietary inflammatory index and non-communicable

disease risk: A narrative review. Nutrients.

11(1873)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Huang Y, Kypridemos C, Liu J, Lee Y,

Pearson-Stuttard J, Collins B, Bandosz P, Capewell S, Whitsel L,

Wilde P, et al: Cost-effectiveness of the US food and drug

administration added sugar labeling policy for improving diet and

health. Circulation. 139:2613–2624. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lee Y, Mozaffarian D, Sy S, Huang Y, Liu

J, Wilde PE, Abrahams-Gessel S, Jardim TSV, Gaziano TA and Micha R:

Cost-effectiveness of financial incentives for improving diet and

health through medicare and medicaid: A microsimulation study. PLoS

Med. 16(e1002761)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Chekanov K: Diversity and distribution of

carotenogenic Algae in Europe: A review. Mar Drugs.

21(108)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Elbahnaswy S and Elshopakey GE: Recent

progress in practical applications of a potential carotenoid

astaxanthin in aquaculture industry: A review. Fish Physiol

Biochem. 50:97–126. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Azam MS, Choi J, Lee MS and Kim HR:

Hypopigmenting effects of brown algae-derived phytochemicals: A

review on molecular mechanisms. Mar Drugs. 15(297)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hentati F, Tounsi L, Djomdi D, Pierre G,

Delattre C, Ursu AV, Fendri I, Abdelkafi S and Michaud P: Bioactive

polysaccharides from seaweeds. Molecules. 25(3152)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kiran BR and Venkata Mohan S: Microalgal

cell biofactory-therapeutic, nutraceutical and functional food

applications. Plants (Basel). 10(836)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ren Y, Deng J, Huang J, Wu Z, Yi L, Bi Y

and Chen F: Using green alga Haematococcus pluvialis for

astaxanthin and lipid co-production: Advances and outlook.

Bioresour Technol. 340(125736)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Mularczyk M, Michalak I and Marycz K:

Astaxanthin and other nutrients from Haematococcus

pluvialis-multifunctional applications. Mar Drugs.

18(459)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Davinelli S, Nielsen ME and Scapagnini G:

Astaxanthin in skin health, repair, and disease: A comprehensive

review. Nutrients. 10(522)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Basiony M, Ouyang L, Wang D, Yu J, Zhou L,

Zhu M, Wang X, Feng J, Dai J, Shen Y, et al: Optimization of

microbial cell factories for astaxanthin production: Biosynthesis

and regulations, engineering strategies and fermentation

optimization strategies. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 7:689–704.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wu Y, Shamoto-Nagai M, Maruyama W, Osawa T

and Naoi M: Phytochemicals prevent mitochondrial membrane

permeabilization and protect SH-SY5Y cells against apoptosis

induced by PK11195, a ligand for outer membrane translocator

protein. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 124:89–98. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ostrom QT, Patil N, Cioffi G, Waite K,

Kruchko C and Barnholtz-Sloan JS: CBTRUS statistical report:

Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in

the United States in 2013-2017. Neuro Oncol. 22 (Suppl 2):iv1–iv96.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Tan AC, Ashley DM, López GY, Malinzak M,

Friedman HS and Khasraw M: Management of glioblastoma: State of the

art and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin. 70:299–312.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Shin J, Nile A, Saini RK and Oh JW:

Astaxanthin sensitizes low SOD2-expressing GBM cell lines to TRAIL

treatment via pathway involving mitochondrial membrane

depolarization. Antioxidants (Basel). 11(375)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Shin J, Saini RK and Oh JW: Low dose

astaxanthin treatments trigger the hormesis of human astroglioma

cells by up-regulating the cyclin-dependent kinase and

down-regulated the tumor suppressor protein P53. Biomedicines.

8(434)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Patel M, Singh P, Gandupalli L and Gupta

R: Identification and evaluation of survival-associated common

chemoresistant genes in cancer. Biomed Biotechnol Res J. 8:320–327.

2024.

|

|

28

|

Tsuji S, Nakamura S, Maoka T, Yamada T,

Imai T, Ohba T, Yako T, Hayashi M, Endo K, Saio M, et al:

Antitumour effects of astaxanthin and adonixanthin on glioblastoma.

Mar Drugs. 18(474)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zheng M, Kumar A, Sharma V, Behl T, Sehgal

A, Wal P, Shinde NV, Kawaduji BS, Kapoor A, Anwer MK, et al:

Revolutionizing pediatric neuroblastoma treatment: Unraveling new

molecular targets for precision interventions. Front Cell Dev Biol.

12(1353860)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Sun SQ, Du FX, Zhang LH, Hao-Shi Gu FY,

Deng YL and Ji YZ: Prevention of STAT3-related pathway in SK-N-SH

cells by natural product astaxanthin. BMC Complement Med Ther.

23(430)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wu H, Niu H, Shao A, Wu C, Dixon BJ, Zhang

J, Yang S and Wang Y: Astaxanthin as a potential neuroprotective

agent for neurological diseases. Mar Drugs. 13:5750–5766.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

García F, Lobos P, Ponce A, Cataldo K,

Meza D, Farías P, Estay C, Oyarzun-Ampuero F, Herrera-Molina R,

Paula-Lima A, et al: Astaxanthin counteracts excitotoxicity and

reduces the ensuing increases in calcium levels and mitochondrial

reactive oxygen species generation. Mar Drugs.

18(335)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zhang J, Ding C, Zhang S and Xu Y:

Neuroprotective effects of astaxanthin against oxygen and glucose

deprivation damage via the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β/Nrf2 signalling pathway

in vitro. J Cell Mol Med. 24:8977–8985. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Yan T, Ding F, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang Y,

Zhang Y, Zhu F, Zhang G, Zheng X, Jia G, et al: Astaxanthin

inhibits H2O2-induced excessive mitophagy and

apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells by regulation of Akt/mTOR activation.

Mar Drugs. 22(57)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Korczowska-Łącka I, Słowikowski B, Piekut

T, Hurła M, Banaszek N, Szymanowicz O, Jagodziński PP, Kozubski W,

Permoda-Pachuta A and Dorszewska J: Disorders of endogenous and

exogenous antioxidants in neurological diseases. Antioxidants

(Basel). 12(1811)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Łukasiewicz S, Czeczelewski M, Forma A,

Baj J, Sitarz R and Stanisławek A: Breast cancer-epidemiology, risk

factors, classification, prognostic markers, and current treatment

strategies-an updated review. Cancers (Basel).

13(4287)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ahn YT, Kim MS, Kim YS and An WG:

Astaxanthin reduces stemness markers in BT20 and T47D breast cancer

stem cells by inhibiting expression of pontin and mutant p53. Mar

Drugs. 18(577)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Badak B, Aykanat NEB, Kacar S, Sahinturk

V, Arik D and Canaz F: Effects of astaxanthin on metastasis

suppressors in ductal carcinoma. A preliminary study. Ann Ital

Chir. 92:565–574. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Karimian A, Mir Mohammadrezaei F,

Hajizadeh Moghadam A, Bahadori MH, Ghorbani-Anarkooli M, Asadi A

and Abdolmaleki A: Effect of astaxanthin and melatonin on cell

viability and DNA damage in human breast cancer cell lines. Acta

Histochem. 124(151832)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Kim MS, Ahn YT, Lee CW, Kim H and An WG:

Astaxanthin modulates apoptotic molecules to induce death of SKBR3

breast cancer cells. Mar Drugs. 18(266)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Lu Z, Long Y, Li J, Li J, Ren K, Zhao W,

Wang X, Xia C, Wang Y, Li M, et al: Simultaneous inhibition of

breast cancer and its liver and lung metastasis by blocking

inflammatory feed-forward loops. J Control Release. 338:662–679.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

McCall B, McPartland CK, Moore R,

Frank-Kamenetskii A and Booth BW: Effects of astaxanthin on the

proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells in vitro.

Antioxidants (Basel). 7(135)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Shokrian Zeini M, Pakravesh SM, Jalili

Kolour SM, Soghala S, Dabbagh Ohadi MA, Ghanbar Ali Akhavan H,

Sayyahi Z, Mahya L, Jahani S, Shojaei Baghini S, et al: Astaxanthin

as an anticancer agent against breast cancer: An in vivo and in

vitro investigation. Curr Med Chem: Apr 17, 2024 (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

44

|

Vijay K, Sowmya PRR, Arathi BP, Shilpa S,

Shwetha HJ, Raju M, Baskaran V and Lakshminarayana R: Low-dose

doxorubicin with carotenoids selectively alters redox status and

upregulates oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis in breast cancer

cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 118:675–690. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Malhão F, Ramos AA, Macedo AC and Rocha E:

Cytotoxicity of seaweed compounds, alone or combined to reference

drugs, against breast cell lines cultured in 2D and 3D. Toxics.

9(24)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Sowmya PRR, Arathi BP, Vijay K, Baskaran V

and Lakshminarayana R: Astaxanthin from shrimp efficiently

modulates oxidative stress and allied cell death progression in

MCF-7 cells treated synergistically with β-carotene and lutein from

greens. Food Chem Toxicol. 106:58–69. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Yuri T, Yoshizawa K, Emoto Y, Kinoshita Y,

Yuki M and Tsubura A: Effects of dietary xanthophylls,

canthaxanthin and astaxanthin on N-Methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced rat

mammary carcinogenesis. In Vivo. 30:795–800. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Fouad MA, Sayed-Ahmed MM, Huwait EA, Hafez

HF and Osman AMM: Epigenetic immunomodulatory effect of eugenol and

astaxanthin on doxorubicin cytotoxicity in hormonal positive breast

Cancer cells. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 22(8)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Atalay PB, Kuku G and Tuna BG: Effects of

carbendazim and astaxanthin co-treatment on the proliferation of

MCF-7 breast cancer cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 55:113–119.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Bharathiraja S, Manivasagan P, Quang Bui

N, Oh YO, Lim IG, Park S and Oh J: Cytotoxic induction and

photoacoustic imaging of breast cancer cells using

astaxanthin-reduced gold nanoparticles. Nanomaterials (Basel).

6(78)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Kulpreechanan N and Sorasitthiyanukarn FN:

Astaxanthin-loaded chitosan oligosaccharide/alginate nanoparticles:

Exploring the anti-inflammatory and anticancer potential as a

therapeutic nutraceutical: An in vitro study. Res J Pharm Technol.

16:5378–5383. 2023.

|

|

52

|

Burz C, Pop V, Silaghi C, Lupan I and

Samasca G: Prognosis and treatment of gastric cancer: A 2024

update. Cancers (Basel). 16(1708)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Li H, Shen M and Wang S: Current therapies

and progress in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Front

Oncol. 14(1327055)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer

Collaboration. Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu

MA, Allen C, Al-Raddadi R, Alvis-Guzman N, Amoako Y, et al: The

burden of primary liver cancer and underlying etiologies from 1990

to 2015 at the global, regional, and national level: Results from

the global burden of disease study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 3:1683–1691.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Mazzaferro V, Citterio D, Bhoori S,

Bongini M, Miceli R, De Carlis L, Colledan M, Salizzoni M,

Romagnoli R, Antonelli B, et al: Liver transplantation in

hepatocellular carcinoma after tumour downstaging (XXL): A

randomised, controlled, phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21:947–956.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Shao Y, Ni Y, Yang J, Lin X, Li J and

Zhang L: Astaxanthin inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis

and cell cycle arrest of mice H22 hepatoma cells. Med Sci Monit.

22:2152–2160. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Zhang X, Li W, Dou X, Nan D and He G:

Astaxanthin encapsulated in biodegradable calcium alginate

microspheres for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in

vitro. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 191:511–527. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Messina CM, Manuguerra S, Renda G and

Santulli A: Biotechnological applications for the sustainable use

of marine by-products: In vitro antioxidant and pro-apoptotic

effects of astaxanthin extracted with supercritical CO2

from parapeneus longirostris. Mar Biotechnol (NY). 21:565–576.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Li J, Dai W, Xia Y, Chen K, Li S, Liu T,

Zhang R, Wang J, Lu W, Zhou Y, et al: Astaxanthin inhibits

proliferation and induces apoptosis of human hepatocellular

carcinoma cells via inhibition of Nf-Κb P65 and Wnt/Β-catenin in

vitro. Mar Drugs. 13:6064–6081. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Yadav K, Saxena A, Gupta M, Saha B, Sarwat

M and Rai MP: Comparing pharmacological potential of freshwater

microalgae carotenoids towards antioxidant and anti-proliferative

activity on liver cancer (HUH7) cell line. Appl Biochem Biotechnol.

196:2053–2066. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Ren P, Yu X, Yue H, Tang Q, Wang Y and Xue

C: Dietary supplementation with astaxanthin enhances anti-tumor

immune response and aids the enhancement of molecularly targeted

therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Food Funct. 14:8309–8320.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Ren P, Tang Q, He X, Xu J, Wang Y and Xue

C: Astaxanthin augmented the anti-hepatocellular carcinoma efficacy

of sorafenib through the inhibition of the JAK2/STAT3 signaling

pathway and mitigation of hypoxia within the tumor

microenvironment. Mol Nutr Food Res. 68(e2300569)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY,

Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu

JCY, et al: Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori

infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology.

153:420–429. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Kim SH and Kim H: Transcriptome analysis

of the inhibitory effect of astaxanthin on Helicobacter

pylori-induced gastric carcinoma cell motility. Mar Drugs.

18(365)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Lee H, Lim JW and Kim H: Effect of

astaxanthin on activation of autophagy and inhibition of apoptosis

in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric epithelial cell line

AGS. Nutrients. 12(1750)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Kim SH and Kim H: Inhibitory effect of

astaxanthin on gene expression changes in Helicobacter

pylori-infected human gastric epithelial cells. Nutrients.

13(4281)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Lee J, Lim JW and Kim H: Astaxanthin

inhibits matrix metalloproteinase expression by suppressing

PI3K/AKT/mTOR activation in Helicobacter pylori-infected

gastric epithelial cells. Nutrients. 14(3427)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Woo J, Lim JW and Kim H: Astaxanthin

inhibits integrin α5 expression by suppressing activation of

JAK1/STAT3 in Helicobacter pylori-stimulated gastric

epithelial cells. Mol Med Rep. 27(127)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Kim JH, Park JJ, Lee BJ, Joo MK, Chun HJ,

Lee SW and Bak YT: Astaxanthin inhibits proliferation of human

gastric cancer cell lines by interrupting cell cycle progression.

Gut Liver. 10:369–374. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Kim S, Lee H, Lim JW and Kim H:

Astaxanthin induces NADPH oxidase activation and

receptor-interacting protein kinase 1-mediated necroptosis in

gastric cancer AGS cells. Mol Med Rep. 24(837)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Han H, Lim JW and Kim H: Astaxanthin

inhibits Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammatory and

oncogenic responses in gastric mucosal tissues of mice. J Cancer

Prev. 25:244–251. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|