Introduction

Pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH) refers to a group

of genetic, progressive disorders mostly affecting the

infratentorial structures with the involvement of the cerebellum,

pons and olivary nuclei, associated with atrophic changes of

supratentorial structures: The cerebral cortex and basal ganglia.

The actual classification is based on the identification of

underlying molecular defects leading to the current recognition of

17 PCH types associated with 25 different genes. Based on the

underlying molecular pathways, PCH may result from alteration in

genes targeting transfer (t)RNA processing (I), other forms of RNA

processing (II) or result from mutations in genes not related to

RNA processing (1).

PCH2D is caused by mutation of the gene encoding

O-phosphoseryl-tRNA selenocysteine (SEC):selenocysteinyl-tRNA

synthase [SEPSECS (chr.4p15.2)]. This enzyme converts SEC to

selenocystenenyl-tRNA in a process relying on the presence of the

selenocysteine tRNA (tRNASec) and pyridoxal-5-phosphate.

Sec-tRNASec acts as a selenium donor in selenoprotein biosynthesis.

Mice with neuronal selenoprotein deficiency show marked cerebellar

hypoplasia, associated with Purkinje cell death and decreased

granule cell proliferation, indicating that selenoproteins are

required for proper cerebellar development (2). The selenoproteins glutathione (GSH)

peroxidase (GPXs) and selenoprotein H (SelH) have critical roles in

the GSH-dependent and antioxidant systems, providing protection

from reactive oxygen species (ROS). SelH increases the expression

of the GSH-synthesis enzyme γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase, whereas

GPXs catalyse the breakdown of peroxides into water (3).

To date, a total of 26 patients with PCH2D have been

reported (1,4-21)

with different mutant alleles and variable clinical phenotypes,

exhibiting a certain degree of heterogeneity in terms of

manifestations and severity. Progressive pontocerebellar and

cerebral atrophy, microcephaly and mostly severe developmental

disability are prominent neurological features.

The present study reports on a patient harbouring a

novel SEPSECS mutation and presenting with postnatal

microcephaly, progressive motor and intellectual disability, visual

defect and progressive cerebral and pontocerebellar atrophy, as

well as recurrent blood lactate elevation. In light of the acute

neurological regression following vaccination with fever in the

present case, not previously reported in PCH2D, the clinical

spectrum associated with SEPSECS mutations was reviewed with

an emphasis on the causal link between selenoprotein biosynthesis

deficiency and mitochondrial disorders.

Case report

Case presentation

The pediatric patient was male and born full-term

(40th week of gestation) after an uncomplicated pregnancy, with an

uneventful neonatal period. At birth, the body weight was 3.2 Kg

(25th pc), and the length was 48 cm (25-50th pc), both in the

normal range (25-75th pc) according to the Neonatal Anthropometric

Charts for Italy (https://www.siedp.it). Head circumference (HC) was in

the low-normal range (33 cm, 10th pc). Early psychomotor

development was normal: Head control was gained at 3 months and

sitting with support was achieved at 5 months. Following

meningococcal vaccination at the age of six months, the patient

experienced high fever (39˚C) associated with a seizure episode,

followed by the acute onset of convergent strabismus and truncal

hypertonia. Neurological examination at the age of 9 months

revealed microcephaly (HC, 41 cm; <<3rd pc), internal

strabismus, severe developmental delay, poor active movements with

limb spasticity, absent handling and inadequate response to

environmental stimuli. The patient was unable to keep his head on

the trunk, sit, crawl and roll. Electroencephalogram (EEG) showed a

prevalence of abnormal background rapid rhythms without epileptic

discharges.

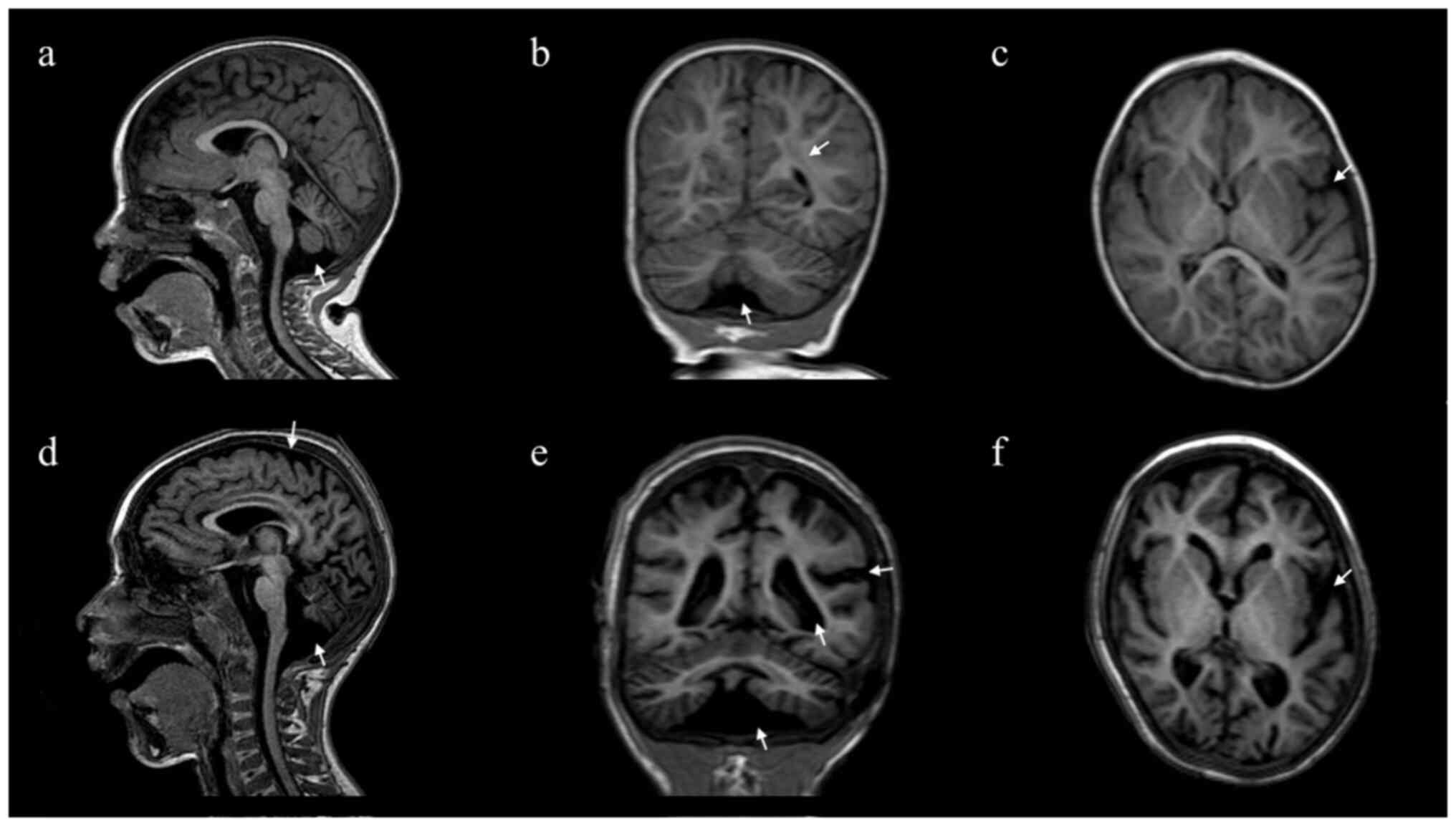

Brain MRI, performed at the age of 19 months, showed

posterior periventricular white matter signal changes bilaterally

and subcortical white matter hyperintensity, particularly in the

insular temporal areas. Neuroimaging of the cerebellum and the

brainstem were otherwise normal.

At 26 months of age, brain MRI showed slight

peritrigonal white matter hyperintensity with a normal corpus

callosum and reduction of the cerebral white matter with

enlargement of the periencephalic and peritruncal cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF) spaces associated with pontobulbar and vermian atrophy

(Fig. 1A-C). Between two and five

years of age, the patient had recurrent seizures associated with

fever. Repeated EEG recording showed hypersynchronous activity in

the central posterior regions.

The patient was first evaluated at our department

(Child and Adolescent Neurology and Psychiatric Section, University

Hospital Policlinico, Department of Clinical and Experimental

Medicine, University of Catania, Catania, Italy), at age 6

(November 2021). On physical examination, a sloping forehead, round

face, thick nasal alae, low-set ears and thin elongated fingers

were noted. Pertinent neurological findings included bilateral

convergent strabismus, microcephaly and spastic quadriplegia with

fixed fits and absent verbal language. The patient had recurrent

episodes with irritability and inconsolable crying when away from

home and daytime episodes of perioral tremor. No improvement with

gradual titration of baclofen and clonazepam per os was

observed over time.

Brain MRI showed slight asymmetric enlargement of

the lateral ventricles, an enlarged fourth ventricle, multiple

areas of altered signal in the peri/supraventricular and

subcortical white matter, as well as deepening of the

temporo-occipital sulci bilaterally. The white-matter volume was

globally reduced with enlargement of subtentorial, pontine and

bulbar cisternae, large cisterna magna and a wide pontocerebellar

angle. There were overt signs of pontobulbar, cerebellar vermis and

hemisphere atrophy with signal alteration in fluid-attenuated

inversion recovery sequences (Fig.

1D-F).

Screening methods

Extensive metabolic screening and Array Comparative

Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) were performed using the SurePrint G3

Custom CGH Microarray, 4x180K (Agilent Technologies, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol, with appropriate Agilent

reference DNAs (Euro male and Euro female). The array data

extraction and analysis were performed using CytoGenomics v.5.0.2.5

(Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The extensive metabolic screening

included quantitative analysis of urinary organic acids by gas

chromatography/mass spectrometry (MS) (22). A blood amino acid (AA) profile was

obtained from dried blood spots (DBS) by electrospray

ionization-tandem MS (ESI-MS) (25 metabolites, including 14 AAs and

11 AA ratios, were simultaneously measured). The following AAs were

determined: Alanine (Ala), arginine (Arg), citrulline (Cit),

glutamate (Glu), glutamine (Gln), glycine (Gly), leucine (Leu),

methionine (Met), ornithine, phenylalanine (Phe), proline, tyrosine

(Tyr) and valine (Val). The following AA ratios were measured:

Leu+Val/Phe+Tyr, Cit/Arg, Cit/Phe, Leu/Phe, Met/Leu, Met/Phe,

Phe/Tyr, Glu/Gln, Tyr/Leu, Tyr/Met and Val/Phe). The anion gap to

check for metabolic acidosis (22)

was determined to measure the difference between the primary

measured cations (sodium and potassium) and the primary measured

anions (chloride and bicarbonate) in serum. Determination of blood

acyl-carnitine levels included measures of short-chain,

medium-chain and long-chain acyl-carnitines from DBS by using

ESI-MS (22). Serum transferrin

glycoform analysis was performed by capillary electrophoresis and

serum lysosomal enzymes (β-hexosaminidase and β-galactosidase) were

measured fluorometrically (23).

Whole blood (3 ml) was collected from the proband

and the proband's parents for NGS analysis after informed consent

had been provided. NGS analyses were performed by Research &

Innovation Genetics Srl (Padua-Italy). DNA library preparation and

whole-exome enrichment were performed using the SureSelect All Exon

V6 kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The library was sequenced

using the NextSeq 2000 Illumina Sequencer (100-bp paired-end reads;

Illumina, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Bioinformatics analysis included the following: i) NGS reads were

aligned to the GRCh37 human reference genome using the

Burrows-Wheeler Alignment tool (https://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/) with the default

parameters; ii) PCR duplicate removal using Picard (http://picard.sourceforge.net); iii) identification of

single nucleotide polymorphisms and insertions/deletions using the

Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK 4; https://gatk.broadinstitute.org/hc/en-us); iv) variant

annotation using snpEff (http://snpeff.sourceforge.net). Whole-exome sequencing

(WES) data and read alignment analysis were checked for coverage

depth and alignment quality using the Bedtools software package

(https://github.com/arq5x/bedtools2).

Variant classification was performed in accordance with the

guidelines from the American College of Medical Genetics and

Genomics (ACMG) (24).

Phenotype-driven analysis, coupled with the employment of in

silico multigene panels specific for microcephaly and

neurodevelopmental disorders, was used to filter, select and

interpret genetic variants obtained following exome sequencing. The

PCR products containing significant variants underwent Sanger

sequencing and capillary electrophoresis using an 3100-avant

automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions (https://tools.thermofisher.com/content/sfs/manuals/cms_041003.pdf).

Findings of the screening

analysis

Extensive metabolic screening, including urinary

organic acids and plasma amino acids, anion gap, serum transferrin

glycoform analyses and lysosomal enzymes yielded normal results.

Isolated, recurrent elevations of lactic acid levels (25 mg/dl at

the age of 12 months and 40.2 mg/dl at around the age of 2 years;

normal range: 5.7-22.0 mg/dl) were detected (Table I). Additional evidence of

mitochondrial dysfunction was found by acyl-carnitine analyses,

illustrating a decrease in blood acetyl-carnitine. This is formed

by the enzyme carnitine acetyltransferase, which transfers a

2-carbon moiety from acetyl-CoA to L-carnitine. A decrease of

acetyl-CoA, the substrate for the synthesis of acetyl-carnitine, is

found in the case of increased oxidative stress due to oxidative

damage, particularly when several key enzymes of acetyl-CoA and

energy metabolism are oxidatively modified (25).

| Table IClinical, neuroimaging and genetic

data of reported patients with SEPSECS mutations. |

Table I

Clinical, neuroimaging and genetic

data of reported patients with SEPSECS mutations.

| First author,

year | Families | Pts | Sex | Mutation | Effect | Genotype | Brain MRI | Microcephaly | Spasticity | Walking | Epilepsy (seizure

type) | Vision | DD/ID | Language | Other | First signs | Mitochondrial

signs | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ben-Zeev, 2003;

Agamy, 2010 | 2 | 4 | M | c.1001A>G | Missense | Homozygous | Cerebellar/cerebral

atrophy | + (secondary) | + | ND | + (generalized,

myoclonic) | Nystagmus | + | Non-verbal | - | ND | - | (4,5) |

| | | | F | c.1001A>G | Missense | Homozygous | Normal at 5 m;

progressive cerebellar/frontal parasylvian atrophy | + (secondary) | + | - | - | ND | + | Non-verbal | Chorea | ND | - | |

| | | | M | c.1001A>c.

715G>A | Missense

missense | Compound

heterozygous | Normal at 5 m;

progressive cerebellar/frontal parasylvian atrophy | + (secondary) | + | - | + (focal,

generalized) | Partial visual

pursuit | + | Non-verbal | Chorea | ND | - | |

| | | | F | c.1001A>G

c.715G>A | Missense

missense | Compound

heterozygous | w.m..changes thin

corpus callosum at 8 m; progressive cerebellar atrophy | + (secondary) | + | - | - | No visual

pursuit | + | Non-verbal | - | ND | - | |

| Makrythanasis,

2014 | 1 | 1 | F | c.1466A>7 | - | Homozygous | Cerebellar vermis

atrophy | + | + | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | - | DD | - | (6) |

| Alazamy, 2015 | 1 | 1 | - | c.1027_1120del | - | Homozygous | - | ND | + | ND | ND | Nystagmus | ND | Dysarthria | - | ND | - | (7) |

| Anttonen, 2015 | 3 | 3 | F | c.974C>G

c.1287C>A | Missense

nonsense | Compound

heterozygous | Early w.m. changes;

progressive cerebellar/cerebral atrophy | ND | + | - | + (infantile

spasms) | Central

blindness | + | Delay | High TSH | Opisthotonus

(birth) | Elevated blood and

CSF lactate | (8) |

| | | | F | c.974C>Gc.

1287C>A | Missense

nonsense | Compound

heterozygous | Early w.m. changes;

progressive cerebellar/cerebral atrophy | ND | + | - | + (infantile

spasms) | Central

blindeness | + | Delay | High TSH | Opisthotonus (1

m) | Elevated blood and

CSF lactate | |

| | | | M | c.974C>G

c.1287C>A | Missense

nonsense | Compound

heterozygous | Progressive

cerebellar and cerebral atrophy | + (primary) | + | - | + | Central visual

defect | + | Delay | - | Opisthotonus (2

m) | Elevated CSF

lactate | |

| Zhu, 2015 | 1 | 1 | F | c.1A>G

c.388+3A>G | Missense

splicing | Compound

heterozygous | Progressive

cerebellar atrophy | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | - | Hypotonia, DD (5

m) | - | (9) |

| Iwama, 2016 | 2 | 2 | F | c.356A>G

c.77delG | - | Compound

heterozygous | Normal at 2 y;

progressive cerebellar/frontoparietal atrophy | + (secondary) | + | Ataxic gait | - | Nystagmus | + | Slurred speech | - | Downward nystagmus

(3 m) | - | (10) |

| | | | F | c.356A>G

c.467G>A | - | Compound

heterozygous | Normal at 5 y;

progressive cerebellar/cerebral atrophy | + (primary) | + | Ataxic gait | - | ND | ND | Slurred speech | - | DD | - | |

| Pavlidou, 2016 | 1 | 1 | M | c.1001T>C | Missense | Homozygosity | Ventricular

widening at 18 m; progressive cerebellar/cerebral atrophy | + (secondary) | + | Quadriplegia | ND | Optic nerve

atrophy | + | Delay | High CK | Hypotonia | Myopathic features;

decreased mitochondrial respiratory chain complex IV at muscle

biopsy | (11) |

| Olson, 2017 | 1 | 1 | M | c.176CC>T | - | Homozygous | w.m changes;

cerebral/pontocerebellar atrophy | + | ND | ND | + (epileptic

encephalopathy) | ND | ND | ND | - | Hypotonia DD | - | (12) |

| Van Dijk, 2018 | 1 | 1 | F | c.1321G>A | Missense | Homozygous | Progressive

cerebellar atrophy | + | - | Broad-based

gait | ND | Horizontal

nystagmus | + | Able to say few

words | - | DD | - | (13) |

| Hengel, 2020 | 1 | 1 | - | c.181A>G | - | Homozygous | Pontocerebellar

hypoplasia | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | - | ND | - | (14) |

| Arrudi-Moreno

2021, | 1 | 1 | F | c.114+3A>G | Splicing

disruption | Homozygous | Normal at 14 m;

progressive pontocerebellar atrophy | + (secondary) | + | Tetraplegia | - | Convergent

strabismus | ND | Able to say few

words | - | DD | - | (15) |

| Nicita, 2022 | 1 | 1 | M | c.865C>T

c.1297T>C | Missense | Compound

heterozygous | Cerebral atrophy;

thin corpus callosum | + | - | Wide-based gait;

bradykinesia | ND | Nystagmus, optic

nerve atrophy | ND | Dysarthria | Dystonia, low

IgA | Head titubation,

ocular nystagmus (13 m) | - | (16) |

| Martinez-Martin,

2022 | 1 | 2 | M | c.1321G>A | Missense | Homozygous | Mild atrophy of

cerebellar vermis | - | Pyramidal

signs | Ataxic gait | - | Convergent

strabismus | + | Scanning

speech | - | Learning

difficulties and motor impairment (7 y) | - | (17) |

| | | | M | c.1321G>A | Missense | Homozygous | Normal | - | - | Unable to walk in

tandem | - | Nystagmus | + | Scanning

speech | - | Motor and language

impairment (5 y) | - | |

| Ramadesikan,

2022 | 1 | 2 | F | c.1A>T

c.846G>A | Loss of function;

splicing disruption | Compound

heterozygous | w.m. changes at

birth; progressive cerebral/pontocerebellar atrophy | + (secondary) | ND | - | + (febrile, later

focal clusters) | Cortical

blindness | + | Non-verbal | - | Abnormal posturing

(birth) | Decreased activity

of complex I -II at muscle biopsy | (18) |

| | | | M | c.1A>T

c.846G>A | Loss of function;

splicing disruption | Compound

heterozygous | Progressive

cerebral/cerebellar atrophy | + (secondary) | ND | - | + (febrile, later

focal clusters) | Cortical vision

imparment | + | Non-verbal | Respiratory

failure | Hypotonia | Decreased activity

of complex I-II at muscle biopsy | |

| Rong, 2022 | 1 | 1 | F | c.701+1G> A

c.194A>G | Splicing;

missense | Compound

heterozygous | Bilateral pallidum

signal changes at 15 m; progressive frontotemporal atrophy | - | ND | ND | - (15 m

seizure-like symptoms) | Esotropia | + | Delay | - | Hypotonia | Limbs myogenic

changes | (19) |

| Zhao, 2022 | 1 | 1 | - | c.628C>T

c.770T>C | - | Compound

heterozygous | Normal at 28 y;

progressive cerebellar atrophy | ND | ND | Ataxic gait | - | ND | + | Slurred speech | Dysphagia | Bradykinesiat 24

y | - | (21) |

| Ghasemi, 2024 | 2 | 2 | M M | c.208T>C | Missense | Homozygous | ND | ND | ND | Motor delay at 3

y | Febrile

seizures | Strabismus | + | Delay | - | ND | - | (1) |

| | | | | c.1274A>G | Missense | Homozygosity | Cerebellar atrophy

at 4 years | ND | + | Ataxia at 4 y | Febrile

seizures | Nystagmus | + | Delay | Neuropathy | DD | - | |

| Present study | 1 | 1 | M | c.114+3A> G

c.440 G>A | Splicing

missense | Compound

heterozygous | w.m. changes at 17

m; progressive pontocerebellar and cerebral atrophy | + (secondary) | + | Tetraplegia | + (febrile seizures

generalized epilepsy) | Convergent

strabismus | + | Non-verbal | - | Squint, hypertonia

following fever | Elevated blood

lactate (25 mg/dl at the age of 12 months and 40.2 mg/dl at around

the age of 2 years; normal range: 5.7-22.0 mg/dl) | - |

aCGH analysis was normal. Sequencing analysis of the

coding exons of the genes included in the genetic panel for the

molecular diagnosis of microcephaly and neurodevelopmental

disorders showed two variants in SEPSECS: A paternal

NM_016955.4:c.114+3A>G and maternal NM_016955.4: c.440G>A

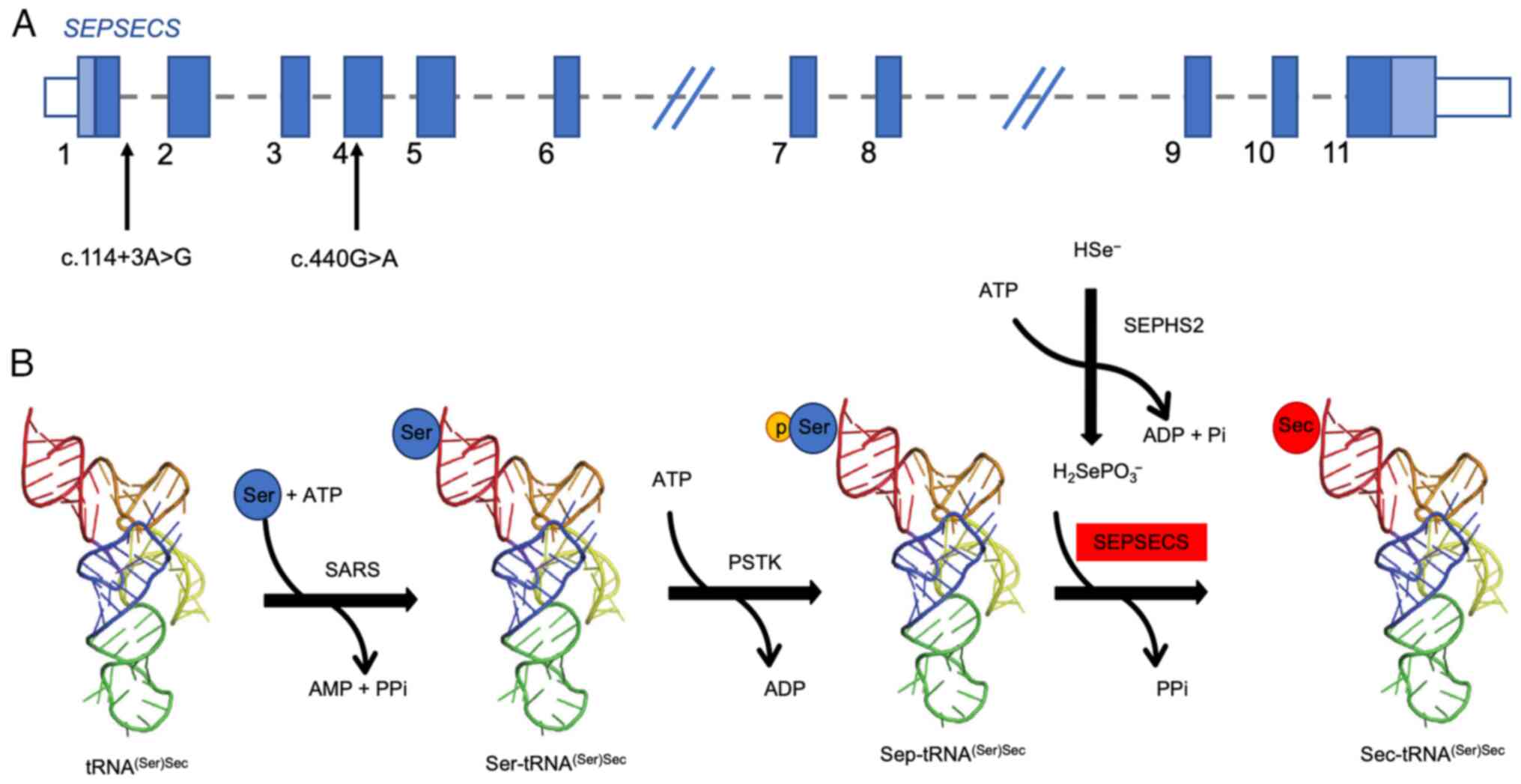

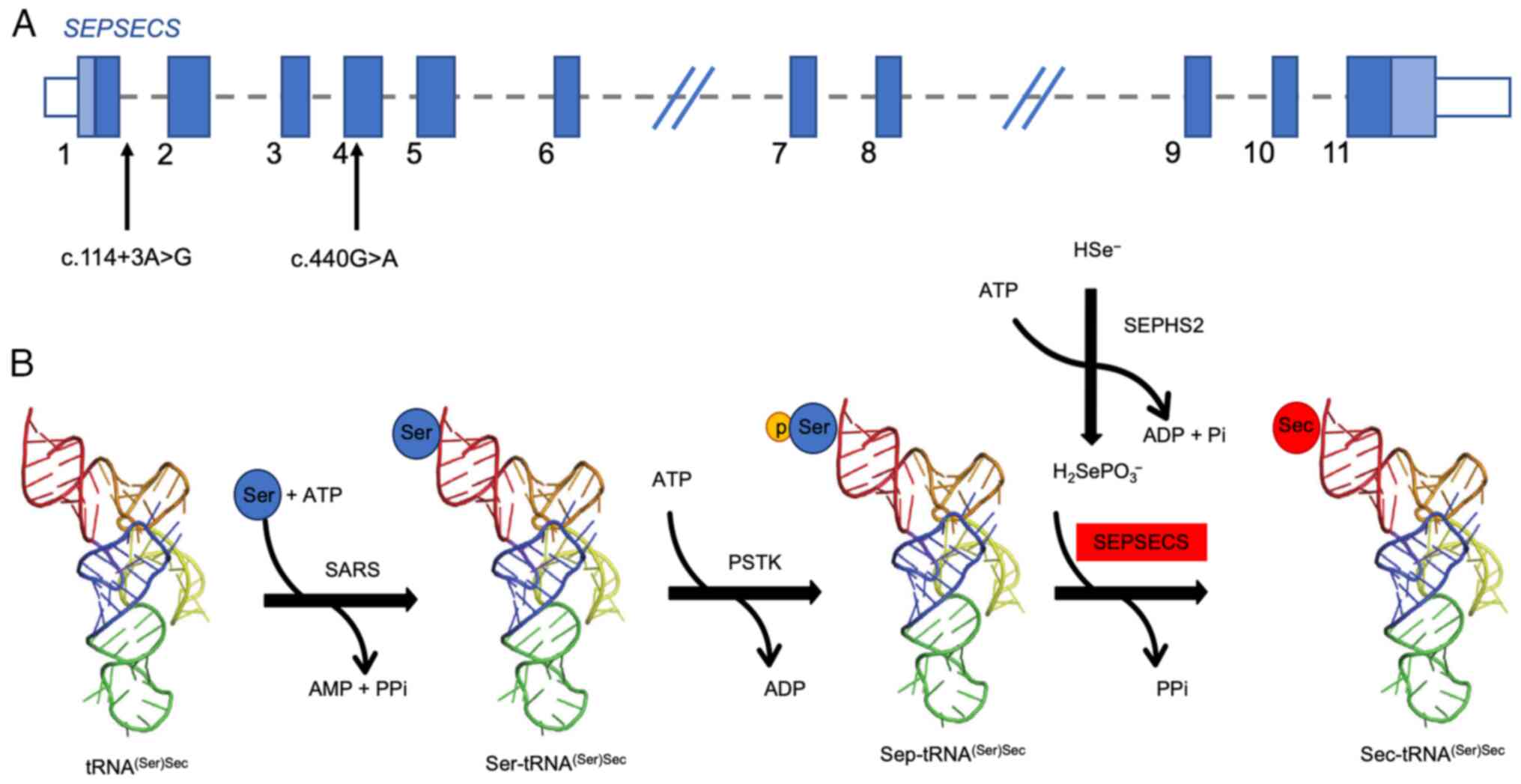

(p.Ser147Asn) (Fig. 2A).

| Figure 2Location of the whole-exome sequencing

variants of the patient within the SEPSECS gene and role of

SepSecS in selenocysteine biosinthesis. (A) The two variants found

in the proband are shown in the schematic representation of the

SEPSECS gene. (B) In humans, Sec-tRNA(Ser)Sec

synthesis follows a two-step process via a phosphorylated

intermediate: tRNA(Ser)Sec is converted to

Ser-tRNA(Ser)Sec, which is phosphorylated to

Sep-tRNA(Ser)Sec.

O-phosphoseryl-tRNA:selenocysteinyl-tRNA synthase, encoded by the

SEPSECS gene, converts Sep-tRNA(Ser)Sec to

Sec-tRNA(Ser)Sec, which acts as a selenium donor in

selenoprotein biosynthesis. SepSeS, O-phosphoseryl-tRNA

selenocysteine:selenocysteinyl-tRNA synthase;

Sec-tRNA(Ser)Sec, selenocysteine tRNA (serine)

selenocysteine; Ser-tRNA(Ser)Sec, seryl tRNA (serine)

selenocysteine; Sep (O-phosphoserine) tRNA, Sec (selenocysteine)

tRNA synthase; Sec-tRNA(Ser)Sec,

selenocysteine-tRNA (serine) selenocysteine. |

The variant c.114+3A>G arises in the consensus

sequence of the splicing donor site (+3 of exon 1). Functional

studies performed on the transcript revealed that it induces exon 1

skipping in the SEPSECS gene, including the translation

initiation codon ATG, thus resulting in a possible loss of function

of the protein (20). The variant

is considered pathogenic according to the ACMG criteria (24).

The variant c.440G>A (p.Ser147Asn) has not been

reported in the medical literature, to the best of our knowledge.

It leads to the substitution of serine at codon 147 by asparagine

in a conserved protein position as measured by PhyloP scores

(https://ionreporter.thermofisher.com/) which measure

evolutionary conservation at individual alignment sites with

positive scores indicating sites that are predicted to be conserved

(PhyloP-Vertebrate=5.64/6.42; phyloP-Primate=0.56/0.65;

PhastCons=1.00/1.00; https://varsome.com/). In silico computational

analysis indicated the harmful effect probability of p.Ser147Asn

amino acid substitution on the structure/activity of the resulting

protein [PolyPhen2=0.996/1.00 (PolyPhen-2: Prediction of functional

effects of human nsSNPs; http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/);

SIFT=0.005/0.00; MutationTaster=1.00/1.00 (https://www.mutationtaster.org/); CADD PHRED=26;

Mutation Assessor=2.85/5.00 (http://mutationassessor.org/r3/)].

According to the ACMG criteria PP3 (multiple

computational evidence supports a deleterious effect on the gene)

and PM3 (absence or extremely low frequency of the variant from

controls in the 1000 Genomes Project, Exome Sequencing Project, or

other large population datasets), the variant can be classified as

likely pathogenic. Both variants were deposited in ClinVar

[accession nos. SCV005061756 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/984624/?oq=SCV005061756&m=NM_016955.4(SEPSECS):c.114%203A%3EG)

and SCV005061752 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/3242529/?oq=SCV005061752&m=NM_016955.4(SEPSECS):c.440G%3EA%20(p.Ser147Asn),

respectively]. No other significant variants were identified in the

whole dataset (dataset available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13234362).

Discussion

To date, 27 patients with ascertained SEPSECS

mutations have been identified, including the present one (Table I). Most patients had an uneventful

pre- and perinatal history with the onset of neurological signs in

the first 2 years of life. A small minority of patients (10,17,21)

had a later onset of neurological symptoms, even in adulthood. In

the most severe phenotypes, patients rapidly experienced an obvious

worsening of clinical conditions, with a post-natal onset of

microcephaly, cerebellar signs and spasticity. Congenital

microcephaly was described in 2 subjects (8,10) and

a normal cranial circumference throughout the follow-up was

reported in 3 patients (17,19).

Motor function impairment was variable with most patients

experiencing spastic quadriplegia, inability to walk and decreased

motor function (12 patients) (4,8,11,15,18)

and the current study. Milder cerebellar symptoms were reported in

milder affected subjects with later disease onset (4 patients).

Choreiform movements (2 patients) (4) and extrapyramidal symptoms resembling

dystonia-parkinsonism (1 patient) (16) were infrequent. Intellectual

disability was an almost constant feature and verbal communication

appeared to be variably affected from the total lack of

communicative skills (4,18) to dysarthria and slurred speech

(21).

Visual impairment was reported in 9 patients

(4,8,11,16,18)

with strabismus and nystagmus as common early signs. Epilepsy,

reported in 7 patients (4,6,8,12,18),

may be either focal or generalized with tonic, myoclonic and

tonic-clonic seizures; 2 patients developed febrile convulsions

with later onset of non-febrile seizures (18) and an additional patient presented

with an early-onset developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with

a burst suppression EEG pattern (12).

Brain MRI was normal in the first months of life in

certain patients. In milder phenotypes (10,17,21),

no alterations were detected even for years, and in one patient,

noticeably, neuroimaging was normal until the age of 28 years

(21). In the majority of patients,

however, white matter changes, particularly in the frontal lobes,

were detected early in infancy and preceded the emergence of

progressive pontocerebellar atrophy associated with cerebral

atrophy. Neuropathological findings included laminar subtotal

necrosis of the neocortex, particularly in the parieto-occipital

regions, myelin loss and gliosis of white matter, consistent with

degeneration secondary to neuronal loss, severe degeneration and

atrophy of the brainstem and cerebellar cortex with an

olivopontocerebellar atrophy-like appearance, subtotal striatal

degeneration and thalamic atrophy (8).

Pathogenic recessive mutations in the SEPSECS

gene have been shown to alter conserved residues and to be mostly

nonsense, missense or inducing splicing disruption. Among the

reported genetic variants, some, like Ala239Thr, Thr325Ser,

Tyr334Cys and Tyr429*, are associated with severe early-onset

phenotypes, reducing protein stability and increasing misfolding,

diminishing the ability of the SepSecS tetramer to bind

tRNASec and affecting the integrity of the active site

(26). Others, such as Gly441Arg,

which was found in homozygosity in subjects with milder and

late-onset phenotypes, may have a less destructive effect on the

catalytic capacity of the enzyme (13).

The current study illustrates a severe early onset

PHC2D type caused by compound heterozygous variants c.114+3A>G

and c.440G>A (p.Ser147Asn), splicing and missense mutations,

respectively. The first variant has been previously described in

homozygosity in two unrelated patients with a severe early-onset

phenotype and classified as likely pathogenic or pathogenic

(15,20). The latter has not been reported in

the literature and dedicated databases, to the best of our

knowledge; it is rare, arises in a conserved protein position and

in silico prediction analysis indicated a probably harmful

effect.

The trace element Selenium (Se) is a vital

micronutrient incorporated into proteins, named selenoproteins, by

the amino acid SEC. Serine is added to tRNASec by seryl-tRNA

synthetase and then modified to phosphoserine by phosphoseryl-tRNA

kinase. Dietary selenium is added to phosphoserine by

selenocysteine synthetase to produce SEC (Fig. 2B). Selenoproteins have critical

roles in both the GSH-dependent and thioredoxin-dependent

antioxidant systems (3).

In the present patient, it appears that acute

neurological regression may have been triggered by fever related to

vaccination, which is a phenomenon observed in patients with

primary mitochondrial diseases (27). Similarities between mitochondrial

disorders and selenoprotein biosynthesis defects have been

emphasized owing to the consolidated role of selenoproteins in

maintaining cellular redox potential and detoxifying

H2O2 (3). In

this regard, recurrent elevation of lactate levels in blood or CSF

was observed in 3 out of four studied patients with PCH2D (8) and in the present one. Furthermore, the

patient of the present study had a depletion of acetyl-L-carnitine

in blood, indicating a deficiency in the regulation of energy

metabolism and oxidative stress, since the acetyl moiety is used

for producing energy and acts as an antioxidant protecting against

oxidative stress (28). Myopathic

features and decreased mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I,

II and IV were found in three studied patients (11,18).

Increased brain protein carbonylation as a sign of oxidative stress

was described post-mortem in patients with SEPSECS

deficiency, as well as moderate liver degeneration resembling

mitochondrial encephalopathy (8).

In sum, the present study was the first report of acute

neurological regression following a catabolic stressor as the

presenting sign of PCH2D. In light of the current understanding of

the potential relationship between selenoprotein defects and

mitochondrial dysfunction (3,8,11,18),

it is important to highlight that patients with SEPSECS

mutations may produce elevated levels of toxic metabolites and ROS

during a catabolic state induced by physiological stressors such as

fasting, fever, illness, trauma or surgery. Therefore, it may be

advisable to consider preventive measures to avoid catabolic

stressors in afflicted patients.

Further studies are necessary to characterize the

role of SEPSECS pathogenic variants in triggering oxidative

damage contributing to a severe neurological presentation of

PCHD2.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Original data generated using WES have been

deposited in the public database Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13234362, accession no.

10.5281/zenodo.13234362). Detected variants were submitted to

ClinVar (https://submit.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/subs/variation_clinvar;

accession nos. SCV005061756 and SCV005061752, respectively).

Additional data generated in the present study are included in the

figures and tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

RB and FP conceptualized the study. RB, FP, VM, FC

and GR performed clinical procedures and acquired data. MF

processed the data generated by WES and deposited them in public

databases. RB, FP and MF checked and confirmed the authenticity of

the raw data. FP and RB were major contributors in writing the

manuscript. RR, MDC, MF and RB reviewed and edited the manuscript.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures performed in this study are part of

the routine clinical care of patients with neurodevelopmental

disorders, performed in accordance with the ethical standards of

the institutional research committee at the University Hospital

Policlinico ‘G. Rodolico-San Marco’ Catania (Catania, Italy) and

with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Written informed consent for all medical procedures was obtained

from the patient's parents.

Patient consent for publication

Written consent for the publication of case data,

medical images, genetic information and data reported within this

article, was obtained from the patient's parents.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ghasemi MR, Tehrani Fateh S, Moeinafshar

A, Sadeghi H, Karimzadeh P, Mirfakhraie R, Rezaei M, Hashemi-Gorji

F, Rezvani Kashani M, Fazeli Bavandpour F, et al: Broadening the

phenotype and genotype spectrum of novel mutations in

pontocerebellar hypoplasia with a comprehensive molecular

literature review. BMC Med Genomics. 17(51)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wirth EK, Bharathi BS, Hatfield D, Conrad

M, Brielmeier M and Schweizer U: Cerebellar hypoplasia in mice

lacking selenoprotein biosynthesis in neurons. Biol Trace Elem Res.

158:203–210. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Bellinger FP, Raman AV, Reeves MA and

Berry MJ: Regulation and function of selenoproteins in human

disease. Biochem J. 422:11–22. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ben-Zeev B, Hoffman C, Lev D, Watemberg N,

Malinger G, Brand N and Lerman-Sagie T: Progressive

cerebellocerebral atrophy: A new syndrome with microcephaly, mental

retardation, and spastic quadriplegia. J Med Genet.

40(e96)2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Agamy O, Ben Zeev B, Lev D, Marcus B, Fine

D, Su D, Narkis G, Ofir R, Hoffmann C, Leshinsky-Silver E, et al:

Mutations disrupting selenocysteine formation cause progressive

cerebello-cerebral atrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 87:538–544.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Makrythanasis P, Nelis M, Santoni FA,

Guipponi M, Vannier A, Béna F, Gimelli S, Stathaki E, Temtamy S,

Mégarbané A, et al: Diagnostic exome sequencing to elucidate the

genetic basis of likely recessive disorders in consanguineous

families. Hum Mutat. 35:1203–1210. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Alazami AM, Patel N, Shamseldin HE, Anazi

S, Al-Dosari MS, Alzahrani F, Hijazi H, Alshammari M, Aldahmesh MA,

Salih MA, et al: Accelerating novel candidate gene discovery in

neurogenetic disorders via whole-exome sequencing of prescreened

multiplex consanguineous families. Cell Rep. 10:148–161.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Anttonen AK, Hilander T, Linnankivi T,

Isohanni P, French RL, Liu Y, Simonović M, Söll D, Somer M,

Muth-Pawlak D, et al: Selenoprotein biosynthesis defect causes

progressive encephalopathy with elevated lactate. Neurology.

85:306–315. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zhu X, Petrovski S, Xie P, Ruzzo EK, Lu

YF, McSweeney KM, Ben-Zeev B, Nissenkorn A, Anikster Y, Oz-Levi D,

et al: Whole-exome sequencing in undiagnosed genetic diseases:

Interpreting 119 trios. Genet Med. 17:774–781. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Iwama K, Sasaki M, Hirabayashi S, Ohba C,

Iwabuchi E, Miyatake S, Nakashima M, Miyake N, Ito S, Saitsu H and

Matsumoto N: Milder progressive cerebellar atrophy caused by

biallelic SEPSECS mutations. J Hum Genet. 61:527–531.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Pavlidou E, Salpietro V, Phadke R,

Hargreaves IP, Batten L, McElreavy K, Pitt M, Mankad K, Wilson C,

Cutrupi MC, et al: Pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 2D and optic

nerve atrophy further expand the spectrum associated with

selenoprotein biosynthesis deficiency. Eur J Paediatr Neurol.

20:483–438. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Olson HE, Kelly M, LaCoursiere CM, Pinsky

R, Tambunan D, Shain C, Ramgopal S, Takeoka M, Libenson MH, Julich

K, et al: Genetics and genotype-phenotype correlations in early

onset epileptic encephalopathy with burst suppression. Ann Neurol.

81:419–429. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

van Dijk T, Vermeij JD, van Koningsbruggen

S, Lakeman P, Baas F and Poll-The BT: A SEPSECS mutation in a

23-year-old woman with microcephaly and progressive cerebellar

ataxia. J Inherit Metab Dis. 41:897–898. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hengel H, Buchert R, Sturm M, Haack TB,

Schelling Y, Mahajnah M, Sharkia R, Azem A, Balousha G, Ghanem Z,

et al: First-line exome sequencing in Palestinian and Israeli Arabs

with neurological disorders is efficient and facilitates disease

gene discovery. Eur J Hum Genet. 28:1034–1043. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Arrudi-Moreno M, Fernández-Gómez A and

Peña-Segura JL: A new mutation in the SEPSECS gene related to

pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 2D. Med Clin (Barc). 156:94–95.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In English,

Spanish).

|

|

16

|

Nicita F, Travaglini L, Bombelli F, Tosi

M, Pro S, Bertini E and D'Amico A: Novel SEPSECS pathogenic

variants featuring unusual phenotype of complex movement disorder

with thin corpus callosum: A case report. Neurol Genet.

8(e661)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Martínez-Martín Á, García-García J,

Díaz-Maroto Cicuéndez I, Quintanilla-Mata ML and Segura T: Bringing

light into the darkness: Autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia due

to a recessive mutation in the SEPSECS gene. Neurologia (Engl Ed).

37:709–710. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ramadesikan S, Hickey S, De Los Reyes E,

Patel AD, Franklin SJ, Brennan P, Crist E, Lee K, White P, McBride

KL, et al: Biallelic SEPSECS variants in two siblings with

pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 2D underscore the relevance of

splice-disrupting synonymous variants in disease. Cold Spring Harb

Mol Case Stud. 8(a006165)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Rong T, Yao R, Deng Y, Lin Q, Wang G, Wang

J, Jiang F and Jiang Y: Case Report: A relatively mild phenotype

produced by novel mutations in the SEPSECS Gene. Front Pediatr.

9(805575)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Schlüter A, Rodríguez-Palmero A, Verdura

E, Vélez-Santamaría V, Ruiz M, Fourcade S, Planas-Serra L, Martínez

JJ, Guilera C, Girós M, et al: Diagnosis of Genetic White Matter

Disorders by Singleton Whole-Exome and Genome Sequencing Using

Interactome-Driven Prioritization. Neurology. 98:e912–e923.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhao R, Zhang L and Lu H: Analysis of the

Clinical Features and Imaging Findings of Pontocerebellar

Hypoplasia Type 2D Caused by Mutations in SEPSECS Gene. Cerebellum.

22:938–946. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Barone R, Alaimo S, Messina M, Pulvirenti

A and Bastin J: MIMIC-Autism Group. Ferro A, Frye RE and Rizzo R: A

Subset of Patients With Autism Spectrum Disorders Show a

Distinctive Metabolic Profile by Dried Blood Spot Analyses. Front

Psychiatry. 9(636)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Barone R, Carchon H, Jansen E, Pavone L,

Fiumara A, Bosshard NU, Gitzelmann R and Jaeken J: Lysosomal enzyme

activities in serum and leukocytes from patients with

carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type IA

(phosphomannomutase deficiency). J Inherit Metab Dis. 21:167–172.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S,

Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, et al: ACMG

Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines

for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus

recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and

Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med.

17:405–424. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Mailloux RJ, Jin X and Willmore WG: Redox

regulation of mitochondrial function with emphasis on cysteine

oxidation reactions. Redox Biol. 2:123–139. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Puppala AK, French RL, Matthies D, Baxa U,

Subramaniam S and Simonović M: Structural basis for early-onset

neurological disorders caused by mutations in human selenocysteine

synthase. Sci Rep. 6(32563)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Muraresku CC, McCormick EM and Falk MJ:

Mitochondrial Disease: Advances in clinical diagnosis, management,

therapeutic development, and preventative strategies. Curr Genet

Med Rep. 6:62–72. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ferreira GC and McKenna MC: L-Carnitine

and Acetyl-L-carnitine Roles and Neuroprotection in Developing

Brain. Neurochem Res. 42:1661–1675. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|