Introduction

Cervical cancer is a public health problem and is

the fourth most prevalent cancer in women worldwide (1). Most women diagnosed in middle- and

low-income countries are in advanced stages. The treatment and

outcome of cervical cancer are determined by the clinical stage of

the patient, which is classified according to the criteria of the

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)

(2). Early stages are commonly

treated with surgery, while for locally advanced cancer the

treatment is concurrent chemoradiation (3). Patients with locally advanced cervical

cancer that respond to concurrent chemoradiation therapy have

increased numbers of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and those with

no response present increased immune reactivity to programmed cell

death receptor-ligand 1 (PD-L1) (4).

For patients with cervical cancer with metastasis

and recurrence, the alternative treatment is immunotherapy.

Anti-programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) is the most used

treatment and the clinical response to anti-PD-1 varies among

different monoclonal anti-PD-1 antibodies. Other options have been

evaluated as combination therapies and improved the treatment

response (5). Patients who received

anti-PD1 and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4

bispecific antibodies and expressed PD-L1 in tumors had an improved

objective response rate compared with those who were negative for

PD-L1 (5,6).

PD-1 and PD-L1 are transmembrane proteins: PD-1 is a

receptor, and its ligand is PD-L1. PD-1 is a negative regulator of

T cells and is involved in the maintenance of immune tolerance

through interaction with its ligand PD-L1(7). Tumor cells overexpress PD-L1 to escape

immune surveillance (8), therefore

the binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 inhibits T-cell activation, playing a

negative role in the anticancer immune response (9). It has been reported that genetic

aberration modifies PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. PD-L1 maps to

chromosome 9p24.1 and amplification of this locus has been reported

in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma. In primary mediastinal

large B-cell lymphomas, renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer and

non-small cell lung cancer, among others, this amplification has

been associated with increased PD-L1 expression (10-14).

PD-1 and PD-L1 were initially identified as membrane

proteins but also found in blood circulation. Soluble immune

checkpoints (sICs) are relevant in cancer. Soluble (s)PD-1 and

sPD-L1 can be released into the circulation because of alternative

splicing, which generates protein variants that lack the

transmembrane domain, or by proteolytic cleavage in the cell

membrane (15-17).

PD-1 is primarily expressed by T-cells, but also by

B cells, natural killer cells, dendritic cells and monocytes. On

the other hand, PD-L1 can be expressed by tumor cells,

cancer-associated fibroblasts and less frequently by epithelial and

endothelial cells, immune cells such as antigen-presenting cells,

activated T and B cells, dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophage

lineage cells (16,18-21).

Therefore, the origin of these soluble proteins in circulation

could be of different cell types and the changes in the levels of

these soluble proteins could be a consequence of changes in their

expression or their release from the cells that express them. sPD-1

has been related to higher expression of the splice variant that

encodes the soluble form (17). For

PD-L1, it has been proposed that increased expression of the

metalloproteases that mediate its proteolytic cleavage of the

membrane could increase the levels of the sPD-L1. In relation to

this, increased levels of sPD-L1 have been associated with higher

expression of these metalloproteases (15,22).

But the exact origin of the soluble forms is not enough

documented.

sPD-1 and sPD-L1 have been evaluated in some cancer

types, and the results revealed that, in most cancers, high sPD-1

and sPD-L1 levels are related to poor prognosis. In Hodgkin

lymphoma, lower levels of sPD-L1 are associated with decreased

progression-free survival (23). In

patients with bladder cancer, higher levels of sPDL-1 were

associated with poorer prognosis, independent of the treatment

method, whether chemotherapy or immune checkpoint inhibitors

(24). In pancreatic adenocarcinoma

and gastrointestinal stromal tumors, higher levels of both sPD-L1

and sPD-L1 correlate with poor survival (25,26).

For patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, sPD-L1 and sPD-1 are,

respectively, a negative and a positive prognostic factor, showing

different behaviors, as has been reported in other cancer types

(27).

In patients with locally advanced cervical cancer,

the effect of concurrent chemoradiotherapy on the serum levels of

sPD-1 and sPD-1 was evaluated, and the results revealed that

treatment increased the levels of sPD-1 and sPD-L1, but there is no

information on the possible role of these changes in the immune

response (28). At present, the

relationships between the serum levels of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 and

clinicopathological characteristics and the clinical outcomes of

cancer remain unclear. Therefore, the current study provides

information about the potential use of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 as

prognostic biomarkers of cervical cancer and their relationships

with clinical outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patients

The present investigation was a prospective and

observational study performed on a cohort of 194 patients diagnosed

with cervical cancer at the Radiotherapy Service of the National

Health Centre, Manuel Avila Camacho, from the Mexican Institute of

Social Security (IMSS; Puebla, Mexico) from November 2017 to

October 2023. Patients included in the study were diagnosed with

cervical cancer by a pathologist and were staged according to the

FIGO system (Stage I, II, III and IV) (2). Patients had not received any previous

treatment. The exclusion criteria included previous or concurrent

cancer, pregnancy, autoimmune sickness or the presence of acute

infection.

The tumor histological types included in the study

were squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma (AC) and

adenosquamous cell carcinoma (ASC). The treatment received by the

patients during the study was chemo-radiotherapy, which was

determined according to their clinical characteristics. No

alternative treatment, such as anti-PD-L1, was applied to the

patients.

The control group included 40 women whose cytology

reports were negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancy.

The exclusion criteria were pregnancy, autoimmune sickness or the

presence of acute infection.

The mean age of patients with cervical cancer was

53.24 years (range, 26-87 years). The mean age of the control group

was 31.7 years (range, 21-60 years).

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved (approval

no. R-2023-2106-004) by the Local Ethics Committee of the IMSS

(Puebla, Mexico). All the women included in the study signed a

consent form before sample collection.

Sample collection

Serum was obtained through phlebotomy, centrifuged

at 4,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C and stored in aliquots at -20˚C

until use. Demographic data, pathological diagnosis, histological

type, tumor differentiation grade, clinical stage and clinical

outcome (total remission of disease or death) were collected from

the clinical records.

Serum sPD-1 and sPD-L1 ELISA

To determine the sPD-1 serum concentration, the

Quantikine ELISA Human PD1 Kit (cat. no. DPD10; R&D Systems,

Inc.) was used. Serum PD-L1 levels were determined via a

PD-L1/B7-H1 Quantikine ELISA kit (cat. no. DB7H10; R&D Systems,

Inc.). No serum dilution was performed and each sample was analyzed

in duplicate. The absorbance of the plates was read in a BioTek

Synergy-4 plate reader (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) at 450 nm and

the absorbance at 570 nm was subtracted. The average of the

duplicates of each sample was calculated and the sPD-L1 and sPD-L1

concentrations were calculated via a standard curve provided with

the kit.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney test was performed to compare the

serum levels of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 in the control and cervical cancer

groups, between the keratinizing types and between the clinical

outcomes. The Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's test was

performed to compare the serum levels of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 between

the different clinicopathological characteristics, such as

histological type, differentiation grade and clinical stage. Data

are presented as the medians and ranges. P≤0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Additionally, Spearman's correlation analysis was

used to analyze the correlation between sPD-1 and sPD-L1

concentrations. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism version 10.2.3 (Dotmatics) for Windows.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

analysis was performed to determine the diagnostic value of sPD-1

and sPD-L1. In this ROC curve, the point with the maximum

sensitivity and specificity was selected as the cut-off value. ROC

curve analysis was performed with the method of DeLong et al

(29) using MedCalc software

version 22.030 (MedCalc software, Ltd.).

Results

Patient characteristics

The clinicopathological characteristics considered

in the present study were histological type, keratinizing,

differentiation grade, clinical stage and clinical outcome (total

remission and death). The numbers of patients included in the

different clinicopathological groups are shown in Table I.

| Table IClinicopathological characteristics of

patients with cervical cancer. |

Table I

Clinicopathological characteristics of

patients with cervical cancer.

| Characteristics | Number |

|---|

| Histological

type | SCC | AC | ASC |

| | 156 | 28 | 10 |

| Keratinizing

type | Keratinizing |

Non-Keratinizing |

| | 77 | 30 |

| Differentiation

grade | G1 | G2 | G3 |

| | 11 | 101 | 47 |

| Clinical stage | I | II | III | IV |

| | 17 | 68 | 68 | 24 |

| Clinical

outcome | Total

remission | Deceased |

| | 15 | 7 |

sPD-1 and sPD-L1 concentrations are

increased in patients with cervical cancer

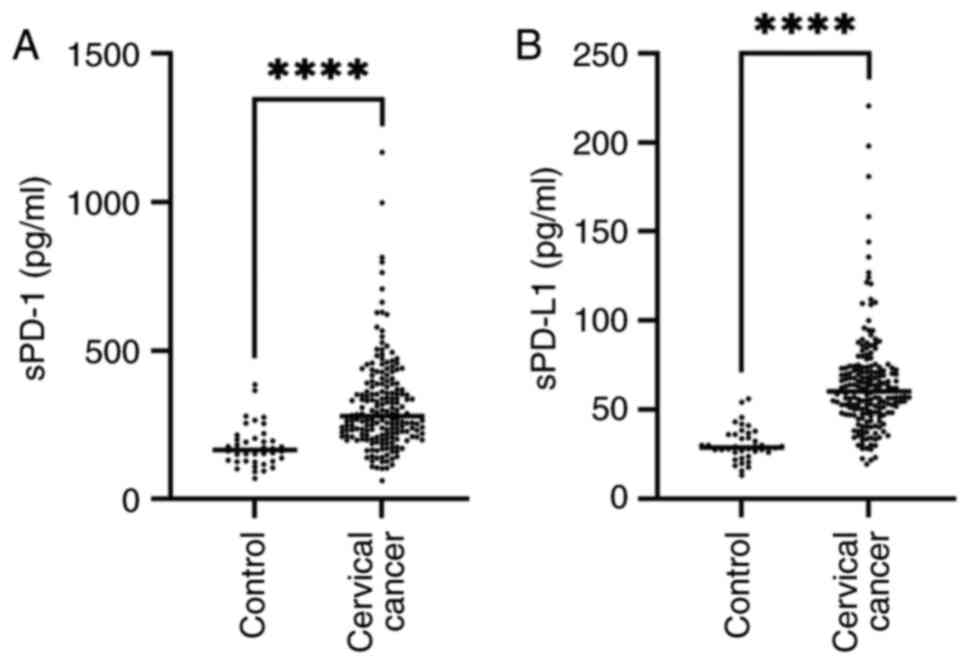

The sPD-1 and sPD-L1 concentrations increased

significantly in the patients with cervical cancer (Fig. 1A and B). The median concentration of sPD-1 in

the control group was 165.3 pg/ml (range, 69.96-385 pg/ml) while it

was 279.4 pg/ml (range, 62.48-1,168.35 pg/ml) in the cervical

cancer group. The median concentration of sPD-L1 in the control

group was 28.88 pg/ml (range, 13.25-56.07 pg/ml), while it was

60.38 pg/ml (range, 19.39-220.4 pg/ml) in the cervical cancer

group. The results showed a significantly increased concentration

of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 in the cervical cancer group P<0.0001.

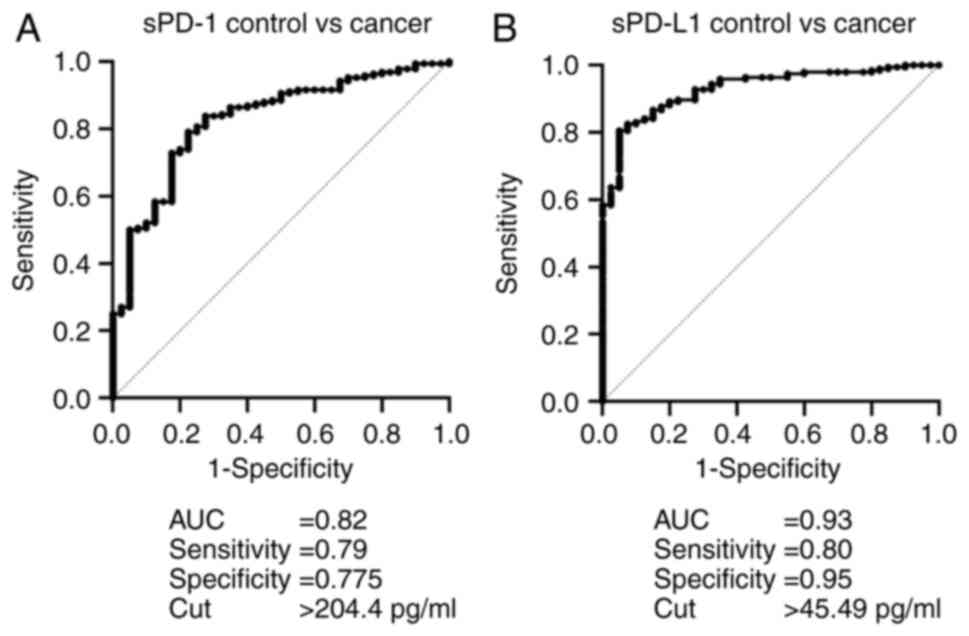

ROC curve analysis

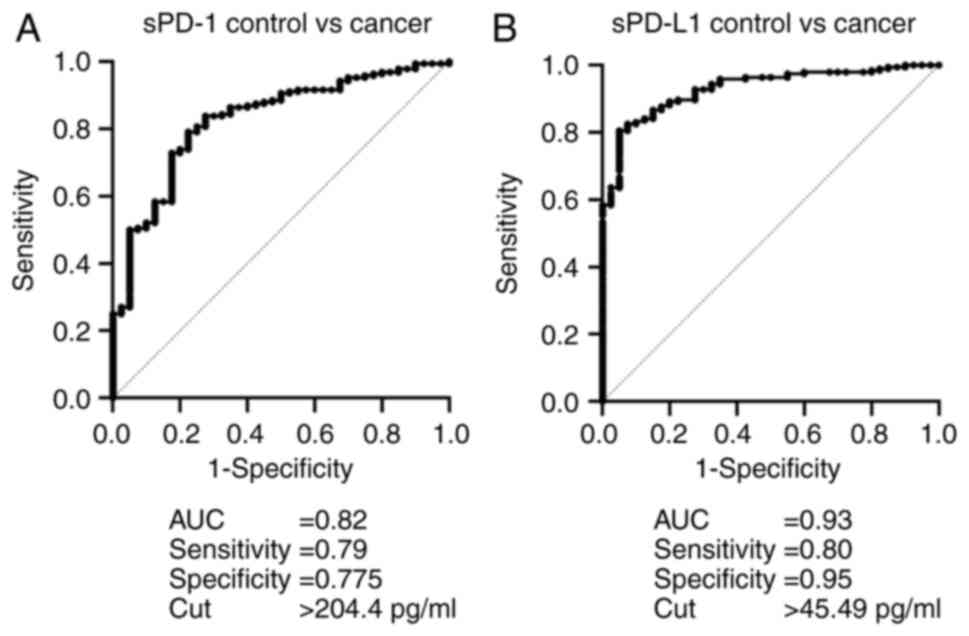

To determine the diagnostic value of sPD-1 and

sPD-L1, ROC curve analysis was performed. The specificity,

sensitivity, area under the curve (AUC) and cut-off values are

shown in Fig. 2A and B. sPD-1 was a favorable discriminator for

patients with cervical cancer with a sensitivity of 0.79 and a

specificity of 0.775; however, sPD-L1 proved superior,

demonstrating a higher sensitivity of 0.80 and a higher specificity

of 0.95. These results support the fact that important changes in

sPD-1 and sPD-L1 levels occur during the development of cervical

cancer, which allows them to be distinguished from healthy

women.

| Figure 2ROC analysis of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 in

the control vs. cervical cancer groups. (A) ROC curve of sPD1 of

the control group (n=40) compared with the cervical cancer group

(n=192); the AUC, sensitivity, specificity, the Youden index and

cut-off value are shown. (B) ROC curve of sPD-L1 of the control

group (n=40) compared with the cervical cancer group (n=194); the

AUC, sensitivity, specificity, the Youden index and cut-off value

are shown. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under

the curve; s, soluble; PD-L1, programmed cell death receptor-ligand

1; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1. |

Relationships of sPD-1 and sPD-L1

concentrations with clinicopathological parameters

sPD-1 and sPD-L1 concentrations were not associated

with histological type, keratinizing type or differentiation grade.

The median concentration of sPD-1 was 269 pg/ml for patients with

SCC, 281.2 pg/ml for patients with AC and 289.83 pg/ml for patients

with ASC (P=0.9143). The median concentration of sPD-L1 was 59.82

pg/ml for patients with SCC, 62.5 pg/ml for patients with AC and

59.22 pg/ml for patients with ASC (P=0.84497). For the keratinizing

type, the median sPD-1 concentration was 284.2 pg/ml while 278.4

pg/ml for the non-keratinizing type (P=0.9533). For sPD-L1, the

median for the keratinizing type was 56.96 pg/ml while for the

non-keratinizing type was 61.23 pg/ml (P=0.4919). Concerning

differentiation grade, a slight increase was observed in the

concentration of both soluble proteins as tumor differentiation

decreased, although it did not reach significance. The median sPD-1

level was 264.4 pg/ml in the well differentiated (G1) group, 267.9

pg/ml in the moderately differentiated (G2) group and 326.4 pg/ml

in the poorly differentiated and undifferentiated (G3) group

(P=0.3749). The median sPD-L1 concentration was 57 pg/ml in the G1

subgroup, 58.92 pg/ml in the G2 subgroup and 63.79 pg/ml in the G3

subgroup (P=0.5576).

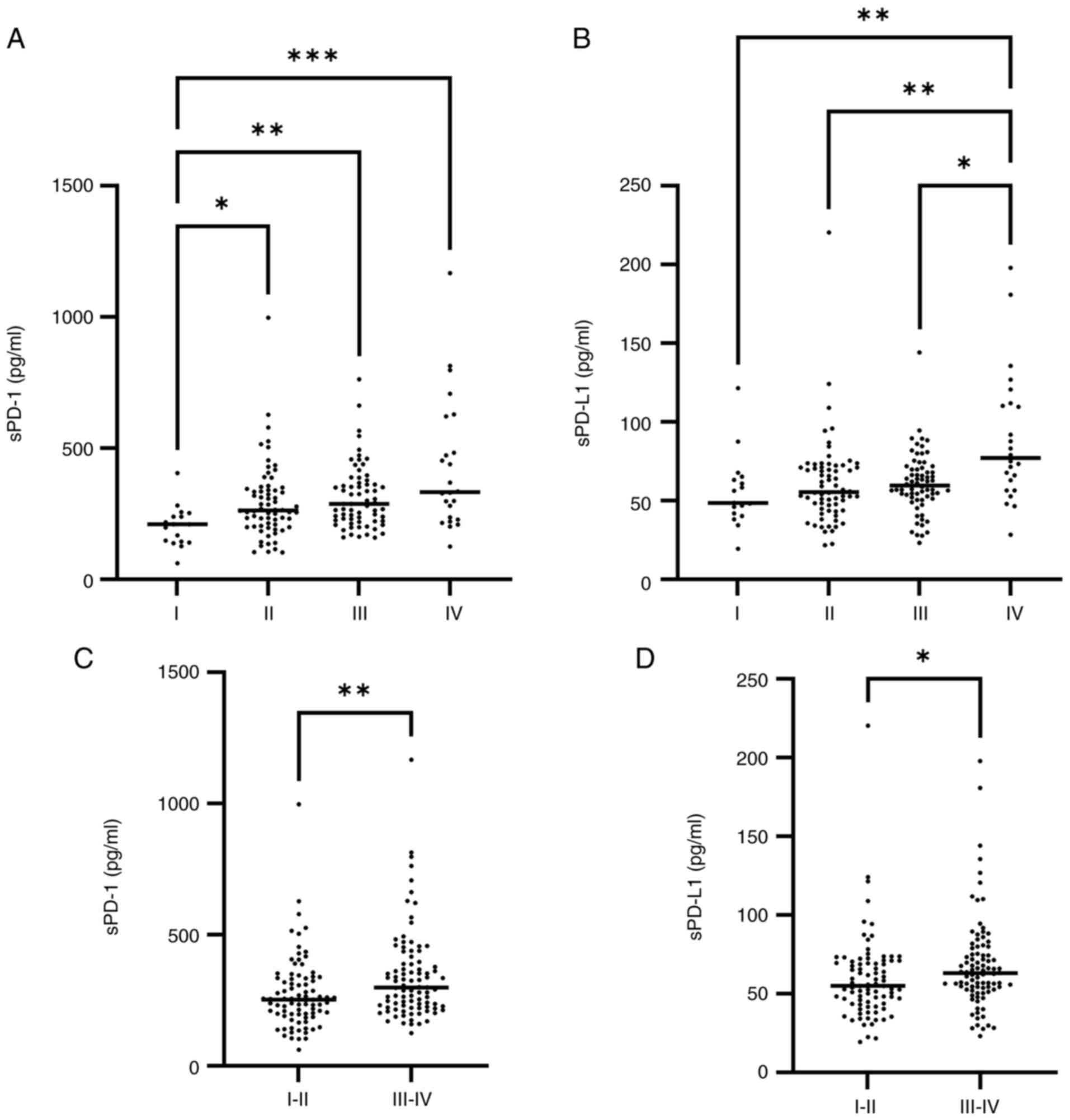

The analysis of sPD-1 concentrations for clinical

stage revealed significantly higher concentrations in patients with

clinical stage II, III and IV than in those with clinical stage I

(Fig. 3A) (P=0.0317, P=0.0025 and

P=0.0001, respectively; Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn's multiple

comparisons test). The sPD-L1 concentration was also significantly

higher in patients with clinical stage IV disease than in those

with stages I, II and III (Fig. 3B)

(P=0.0026, P=0.0021 and P=0.0135, respectively). Analysis of sPD-1

and sPD-L1 in advanced clinical stages (III and IV) vs. early

clinical stages (I and II) indicated significantly higher levels in

advanced clinical stages (Fig. 3C

and D) (P=0.0025 and P=0.0146,

respectively). It is important to highlight that a gradual increase

was observed as the clinical stage progressed, although there were

no significant differences between all groups.

sPD-1 levels are higher in the group

of deceased patients

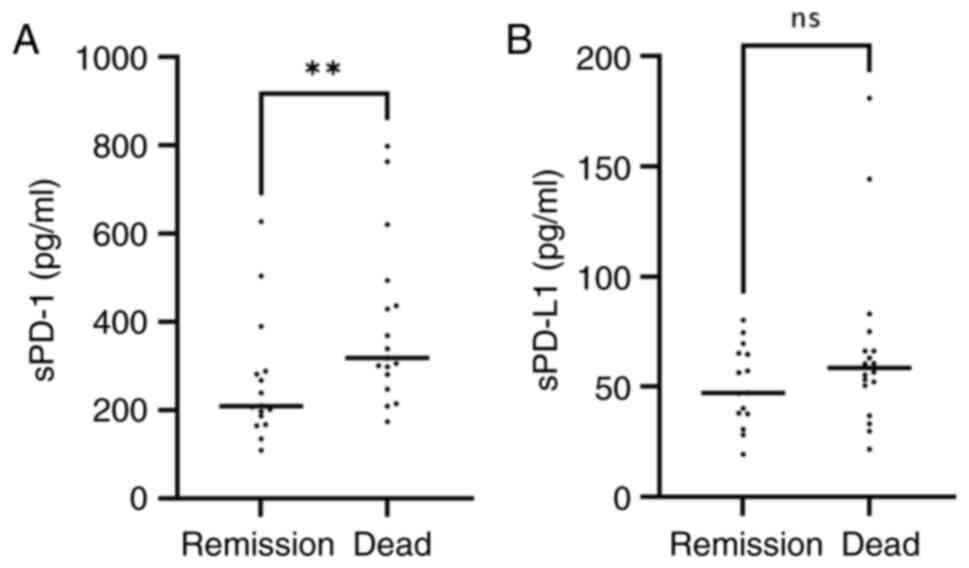

The clinical outcome (total remission or deceased)

was analyzed in relation to the serum levels of sPD-1 or sPD-L1.

The results revealed an increased concentration of both proteins in

the group of deceased patients. The median sPD-1 level was 209.3

pg/ml (range, 109.5-627.52 pg/ml) for the total remission group,

while it was 318.9 pg/ml (range, 174.19-798.72 pg/ml) for the

deceased patients. For sPD-L1, the median concentration in the

total remission group was 47.27 pg/ml (range, 19.39-80.2 pg/ml),

while, in the deceased group, it was 58.51 pg/ml (range,

21.8-180.87 pg/ml); however, the statistical analysis only showed

significant difference for sPD-1 (P=0.0077) (Fig. 4A and B).

Correlations between sPD-1 and sPD-L1

in the control and cervical cancer groups

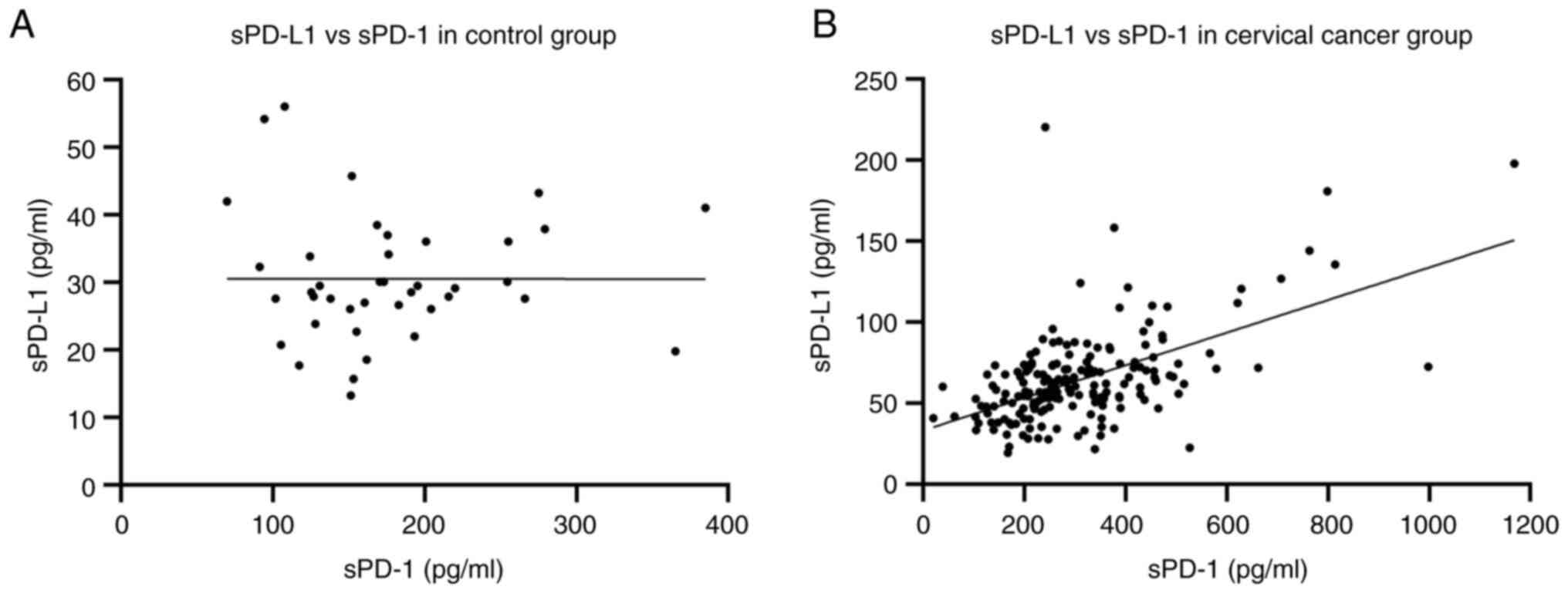

To determine whether there was a correlation between

levels of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 in the control and cervical cancer

groups, a Spearman's correlation analysis was performed. The

results revealed no correlation in the control group, with r=0.066

and P=0.6875 (Fig. 5A). In the

cervical cancer group, the results indicated a strong positive

correlation, with r=0.4660 and P<0.0001 (Fig. 5B). The correlation between these

soluble proteins in the cancer group could be related to the role

of immunosuppression which is not present in the control group.

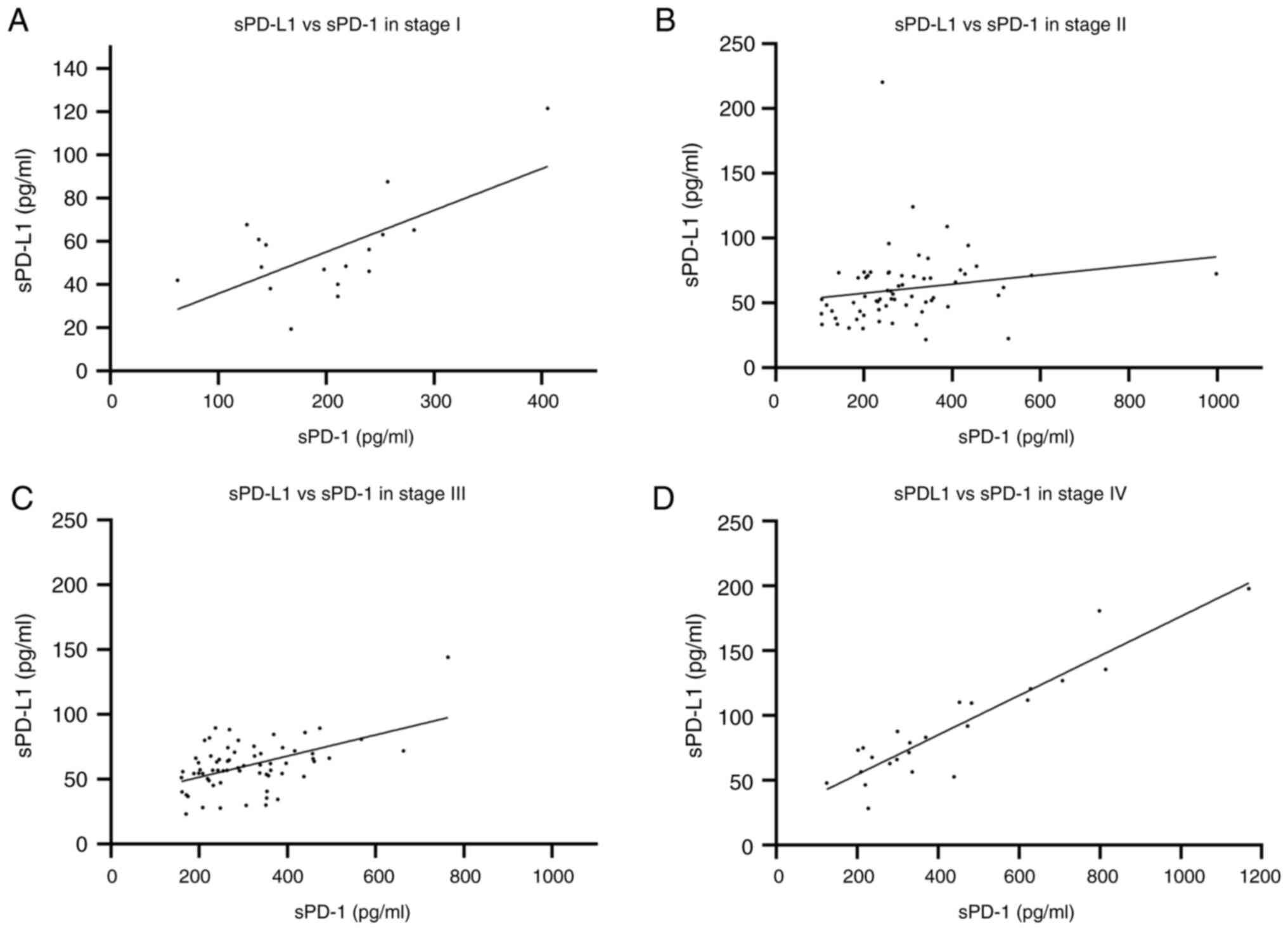

Spearman's correlation of sPD-1 and

sPD-L1 by clinical stage

Additionally, a Spearman's correlation by clinical

stage was performed. The clinical stage I group showed a positive

association (r=0.3676), but this was found non-significant

(P=01471) (Fig. 6A). For patients

at clinical stage II, a moderately positive correlation (r=0.3665)

with P=0.0023 was calculated (Fig.

6B). For patients at clinical stage III, a moderately positive

correlation was detected (r=0.3784) with P=0.017 (Fig. 6C). Clinical stage IV disease was

strongly correlated (r=0.8183 and P<0.0001) (Fig. 6D). The correlation of concentration

of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 increased with diseased progression suggesting

a potential role in the disease progression related with greater

immunosuppression.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the serum concentrations

of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 in patients with cervical cancer to determine

their diagnostic and prognostic value. The serum concentrations of

sPD-1 and sPD-L1 were greater in the cervical cancer group than in

the control group. In other cancer types, increased concentrations

of these soluble proteins were reported in patients with cancer

compared with healthy people. sPD-L1 levels are increased in

patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (23). sPD-1 was evaluated in patients with

associated liver diseases and hepatocellular carcinoma, with higher

levels reported in the cancer group (30,31).

In prostate and non-small cell lung cancer, both soluble proteins

were increased (32,33). These results showed that increased

levels of these sICs are related to cancer. The results of the ROC

curve analysis indicated that both soluble proteins are favorable

discriminators for patients with cervical cancer, with greater

specificity and sensitivity for sPD-L1. These results support the

potential use of these proteins as diagnostic markers and suggest a

role in cancer development as they may participate in immune

tolerance; however, these findings must be further explored.

Analysis of clinicopathological characteristics and

the serum concentrations of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 revealed associations

only with the clinical stage. sPD-1 levels were significantly

higher in patients with clinical stage II, III and IV than in those

with clinical stage I disease. On the other hand, sPD-L1 levels

were significantly higher in patients with clinical stage IV than

in those with clinical stage I, II and III. Additionally, when

early stages I and II were grouped and compared with advanced

stages III and IV, a significant increase was observed in the

advanced clinical stages. In other cancer types, such as extranodal

NK/T-cell lymphoma and gastric cancer, higher levels of sPD-L1 are

related to advanced-stage disease; in non-small cell lung cancer,

higher levels of sPD-1 and sPD-L1 are related to advanced clinical

stage but not to other pathological characteristics, such as the

histological type, as observed in the present study (34,35).

The clinical outcomes of patients with total

remission of the disease and those who succumbed were compared and

the levels of sPD-1 were significantly higher in the deceased

group. sPD-1 has shown inconsistent survival predictive value; for

example, in pancreatic cancer, higher levels of sPD-1 are

associated with survival (25); a

higher concentration of sPD-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma is a

favorable independent prognostic factor and in renal cell carcinoma

it is associated with longer progression-free survival (27,36).

It has been suggested that sPD-1 can promote antitumor immunity by

blocking PD-L1 in tumor cells (37); nonetheless, this result is not

supported by the results obtained in the present study; thus, the

role of sPD-1 in cervical cancer progression must be further

explored. For sPD-L1, increased levels were observed in the

deceased group, but the difference was not statistically

significant; however, in different cancer types, such as

hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric, prostate and renal cell

carcinoma, higher levels were associated with improved survival

(27,32,35,36).

Additionally, in some cancer types like gastric cancer, the

patients with tumors expressing PD-L1 showed low overall survival.

On this basis, it can be hypothesized that in cervical cancer,

sPD-L1 could be secreted by tumor cells and the serum levels be

related to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (38). However, a larger sample size could

increase the accuracy of the present results.

In different types of cancer, analogous elevations

in sPD-1 and sPD-L1 were reported; therefore, the present study

determined the correlation of these soluble proteins in the control

and cervical cancer groups. In the control group, no correlation

was observed, while a favorable correlation was observed in the

cervical cancer group. Additionally, the correlation in the

clinical stage IV group was very strong. The authors of the present

study prefer not to hypothesize on the clinical implications of

these results; however, Hayasi et al (16) reported in 2024 that levels of sCIs

such as sPD-1, sPD-L1 and CTL-4 are related to the exhaustion of

antitumor immunity and the response to immunotherapy because higher

levels of sPD-1 and PD-L1 were associated with non-responsiveness

to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy. An increase in sPD-L1 may

strengthen T-cell inhibition, promoting cancer immune evasion;

however, the roles of both soluble proteins must be studied in

patients with cancer.

Serum sPD-1 and sPD-L1 are potentially accessible

biomarkers that could be used in the diagnosis and prognosis of

patients with cervical cancer and for monitoring patients receiving

anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapy, highlighting the importance of

studying sICs in patients with cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Mexican

Institute of Social Security (grant no. R-2023-2106-004).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SPP and ICR conducted investigation and data

collection. PMM and VVR analyzed data, and designed figures and

table. VVR and JRL conceptualized the study and wrote the

manuscript. ICR and SPP confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors drafted the manuscript, and read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved (approval no.

R-2023-2106-004) by the Human Ethics and Local Committee of the

Mexican Institute of Social Security (Puebla, Mexico). Written

informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the

present study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mohamud A, Høgdall C and Schnack T:

Prognostic value of the 2018 FIGO staging system for cervical

cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 165:506–513. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hsu HC, Li X, Curtin JP, Goldberg JD and

Schiff PB: Surveillance epidemiology and end results analysis

demonstrates improvement in overall survival for cervical cancer

patients treated in the era of concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Front

Oncol. 5(81)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Rocha Martins P, Luciano Pereira Morais K,

de Lima Galdino NA, Jacauna A, Paula SOC, Magalhães WCS, Zuccherato

LW, Campos LS, Salles PGO and Gollob KJ: Linking tumor immune

infiltrate and systemic immune mediators to treatment response and

prognosis in advanced cervical cancer. Sci Rep.

13(22634)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Li C, Cang W, Gu Y, Chen L and Xiang Y:

The anti-PD-1 era of cervical cancer: Achievement, opportunity, and

challenge. Front Immunol. 14(1195476)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lou H, Cai H, Huang X, Li G, Wang L, Liu

F, Qin W, Liu T, Liu W, Wang ZM, et al: Cadonilimab combined with

chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab as first-line treatment in

recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer (COMPASSION-13): A phase 2

study. Clin Cancer Res. 30:1501–1508. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Sharpe AH, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R and Freeman

GJ: The function of programmed cell death 1 and its ligands in

regulating autoimmunity and infection. Nat Immunol. 8:239–245.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ai L, Xu A and Xu J: Roles of PD-1/PD-L1

pathway: Signaling, cancer, and beyond. Adv Exp Med Biol.

1248:33–59. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, Tatiparti K,

Bhise K, Kashaw SK and Iyer AK: PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling

inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: Mechanism, combinations, and

clinical outcome. Front Pharmacol. 8(561)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chen B, Hu J, Hu X, Chen H, Bao R, Zhou Y,

Ye Y, Zhan M, Cai W, Li H and Li HB: DENR controls JAK2 translation

to induce PD-L1 expression for tumor immune evasion. Nat Commun.

13(2059)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Twa DD, Chan FC, Ben-Neriah S, Woolcock

BW, Mottok A, Tan KL, Slack GW, Gunawardana J, Lim RS, McPherson

AW, et al: Genomic rearrangements involving programmed death

ligands are recurrent in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma.

Blood. 123:2062–2065. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Gupta S, Cheville JC, Jungbluth AA, Zhang

Y, Zhang L, Chen YB, Tickoo SK, Fine SW, Gopalan A, Al-Ahmadie HA,

et al: JAK2/PD-L1/PD-L2 (9p24.1) amplifications in renal cell

carcinomas with sarcomatoid transformation: Implications for

clinical management. Mod Pathol. 32:1344–1358. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Gupta S, Vanderbilt CM, Cotzia P,

Arias-Stella JA III, Chang JC, Zehir A, Benayed R, Nafa K, Razavi

P, Hyman DM, et al: Next-generation sequencing-based assessment of

JAK2, PD-L1, and PD-L2 copy number alterations at 9p24.1 in breast

cancer: Potential implications for clinical management. J Mol

Diagn. 21:307–317. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ikeda S, Okamoto T, Okano S, Umemoto Y,

Tagawa T, Morodomi Y, Kohno M, Shimamatsu S, Kitahara H, Suzuki Y,

et al: PD-L1 is upregulated by simultaneous amplification of the

PD-L1 and JAK2 genes in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol.

11:62–71. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Durand I, Alberti L,

Bendriss-Vermare N, Valladeau-Guilemond J, Duc A, Magron A, Morel

AP, Sisirak V, Rodriguez C, et al: A novel regulation of PD-1

ligands on mesenchymal stromal cells through MMP-mediated

proteolytic cleavage. Oncoimmunology. 5(e1091146)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hayashi H, Chamoto K, Hatae R, Kurosaki T,

Togashi Y, Fukuoka K, Goto M, Chiba Y, Tomida S and Ota T: Soluble

immune checkpoint factors reflect exhaustion of antitumor immunity

and response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest.

134(e168318)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Nielsen C, Ohm-Laursen L, Barington T,

Husby S and Lillevang ST: Alternative splice variants of the human

PD-1 gene. Cell Immunol. 235:109–116. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sharpe AH and Pauken KE: The diverse

functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat Rev Immunol.

18:153–167. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wang W and Zhang T: Expression and

analysis of PD-L1 in peripheral blood circulating tumor cells of

lung cancer. Future Oncol. 17:1625–1635. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Bailly C, Thuru X and Quesnel B: Soluble

programmed death ligand-1 (sPD-L1): A pool of circulating proteins

implicated in health and diseases. Cancers (Basel).

13(3034)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kawasaki K, Noma K, Kato T, Ohara T,

Tanabe S, Takeda Y, Matsumoto H, Nishimura S, Kunitomo T, Akai M,

et al: PD-L1-expressing cancer-associated fibroblasts induce tumor

immunosuppression and contribute to poor clinical outcome in

esophageal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 72:3787–3802.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hira-Miyazawa M, Nakamura H, Hirai M,

Kobayashi Y, Kitahara H, Bou-Gharios G and Kawashiri S: Regulation

of programmed-death ligand in the human head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma microenvironment is mediated through matrix

metalloproteinase-mediated proteolytic cleavage. Int J Oncol.

52:379–388. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Guo X, Wang J, Jin J, Chen H, Zhen Z,

Jiang W, Lin T, Huang H, Xia Z and Sun X: High serum level of

soluble programmed death ligand 1 is associated with a poor

prognosis in Hodgkin lymphoma. Transl Oncol. 11:779–785.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Krafft U, Olah C, Reis H, Kesch C, Darr C,

Grünwald V, Tschirdewahn S, Hadaschik B, Horvath O, Kenessey I, et

al: High serum PD-L1 levels are associated with poor survival in

urothelial cancer patients treated with chemotherapy and immune

checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Cancers (Basel).

13(2548)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Bian B, Fanale D, Dusetti N, Roque J,

Pastor S, Chretien AS, Incorvaia L, Russo A, Olive D and Iovanna J:

Prognostic significance of circulating PD-1, PD-L1, pan-BTN3As,

BTN3A1 and BTLA in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Oncoimmunology. 8(e1561120)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Fanale D, Incorvaia L, Badalamenti G, De

Luca I, Algeri L, Bonasera A, Corsini LR, Brando C, Russo A,

Iovanna JL, et al: Prognostic role of plasma PD-1, PD-L1,

pan-BTN3As and BTN3A1 in patients affected by metastatic

gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Can immune checkpoints act as a

sentinel for short-term survival? Cancers (Basel).

13(2118)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chang B, Huang T, Wei H, Shen L, Zhu D, He

W, Chen Q, Zhang H, Li Y, Huang R, et al: The correlation and

prognostic value of serum levels of soluble programmed death

protein 1 (sPD-1) and soluble programmed death-ligand 1 (sPD-L1) in

patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother.

68:353–363. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Liu C, Li X, Li A, Zou W, Huang R, Hu X,

Yu J, Zhang X and Yue J: Concurrent chemoradiotherapy increases the

levels of soluble immune checkpoint proteins in patients with

locally advanced cervical cancer. J Immunol Res.

2022(9621466)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

DeLong ER, DeLong DM and Clarke-Pearson

DL: Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver

operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach.

Biometrics. 44:837–845. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Cheng HY, Kang PJ, Chuang YH, Wang YH, Jan

MC, Wu CF, Lin CL, Liu CJ, Liaw YF, Lin SM, et al: Circulating

programmed death-1 as a marker for sustained high hepatitis B viral

load and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One.

9(e95870)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Li N, Zhou Z, Li F, Sang J, Han Q, Lv Y,

Zhao W, Li C and Liu Z: Circulating soluble programmed death-1

levels may differentiate immune-tolerant phase from other phases

and hepatocellular carcinoma from other clinical diseases in

chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Oncotarget. 8:46020–46033.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Zvirble M, Survila Z, Bosas P,

Dobrovolskiene N, Mlynska A, Zaleskis G, Jursenaite J, Characiejus

D and Pasukoniene V: Prognostic significance of soluble PD-L1 in

prostate cancer. Front Immunol. 15(1401097)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ancın B, Özercan MM, Yılmaz YM, Uysal S,

Kumbasar U, Sarıbaş Z, Dikmen E, Doğan R and Demircin M: The

correlation of serum sPD-1 and sPD-L1 levels with clinical,

pathological characteristics and lymph node metastasis in nonsmall

cell lung cancer patients. Turk J Med Sci. 52:1050–1057.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Li JW, Wei P, Guo Y, Shi D, Yu BH, Su YF,

Li XQ and Zhou XY: Clinical significance of circulating exosomal

PD-L1 and soluble PD-L1 in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma,

nasal-type. Am J Cancer Res. 10:4498–4512. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chivu-Economescu M, Herlea V, Dima S,

Sorop A, Pechianu C, Procop A, Kitahara S, Necula L, Matei L, Dragu

D, et al: Soluble PD-L1 as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in

resectable gastric cancer patients. Gastric Cancer. 26:934–946.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Incorvaia L, Fanale D, Badalamenti G,

Porta C, Olive D, De Luca I, Brando C, Rizzo M, Messina C, Rediti

M, et al: Baseline plasma levels of soluble PD-1, PD-L1, and BTN3A1

predict response to nivolumab treatment in patients with metastatic

renal cell carcinoma: A step toward a biomarker for therapeutic

decisions. Oncoimmunology. 9(1832348)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Qin YE, Tang WF, Xu Y, Wan FR and Chen AH:

Ultrasound-mediated co-delivery of miR-34a and sPD-1 complexed with

microbubbles for synergistic cancer therapy. Cancer Manag Res.

12:2459–2469. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Hassen G, Kasar A, Jain N, Berry S, Dave

J, Zouetr M, Priyanka Ganapathiraju VLN, Kurapati T, Oshai S, Saad

M, et al: Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) positivity and factors

associated with poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer: An

umbrella meta-analysis. Cureus. 14(e23845)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|