Introduction

The incidence of breast cancer (BC) in women always

is increasing and rank first according to statistics in China and

other countries, worldwide (1,2). The

mortality rate of patients with BC ranks second after lung cancer,

which account for ~30% of cancers in women (3,4).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, ~2 million

new patients with BC are diagnosed per year, and this has been

attributed to the increased life span and improved medical care

worldwide (5-7).

Recently, the mortality rate of patients with BC has decreased

because of early screening with mammography and advanced

therapeutic methods, such as targeted and immune therapies

(8-13)

or the combination of ferroptosis with photodynamic therapy

(14). However, for those patients

with advanced BC, 5-year survival rate is only 5-10% (15); therefore, a sensitive and reliable

biomarker is critical for predicting the outcomes of patients with

BC.

Emerging evidence indicates that the detection of

circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in peripheral blood are markedly

related to the recurrence, metastasis and the outcomes of numerous

cancers (16-18).

CTCs originate from primary tumor or metastatic tumors and enter

peripheral circulation, potentially giving rise to tumor cell

proliferation in other parts of the body undergoing

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (16,19-21).

CTCs can be divided into epithelial CTCs (eCTCs), mesenchymal CTCs

(MCTCs) and hybrid CTCs (HCTCs), which express EpCAM and ck8/18/19

as epithelial marker and vimentin combined twist as mesenchymal

marker, respectively (19,22). Initially, EpCAM was considered as a

major marker for epithelial cell because it is a transmembrane

glycoprotein and mediates cell-cell adhesion of epithelial tissues

(23,24), but later cytokeratin 8/18/19CTCs

combined EpCAM measurements to enhance epithelial cell specificity

because cytokeratin 8/18/19 proteins are essential components of

the cytoskeleton in epithelial cells (25,26).

In addition, vimentin was identified as a mesenchymal cell marker

and twist was a relevant transcription factor for mesenchymal cells

(27). Therefore, EMT markers are

more likely to reflect biological functions of CTCs. CTCs'

detecting methods were varied dependent on available equipment and

patients' status, including density-gradient centrifugation,

filtration approaches, flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry (IHC),

glycolysis-associated long non-coding RNAs (IncRNAs) (20), long non-coding RNA detection

(28), and RNA in situ

hybridization (RNA-ISH) (29-32).

Among these techniques, RNA-ISH has numerous advantages over other

methods, such as high sensitivity, less CTCs loss, detecting CTCs

undergoing EMT (33).

The relationship between the numbers of CTCs and the

prognosis of patients with cancer were extensively investigated

(34-37).

Recent studies have revealed that the overall survival (OS) of

patients with higher CTCs number was significantly shorter than

that of patients with low CTCs number (38,39).

Therefore, measurement of the CTCs number is very helpful for

predicting the outcomes of patients with cancer and guiding

treatment decisions.

Recently, Ebright et al (40) identified a ribosomal submit,

ribosomal protein L15 (RPL15) gene, that plays a role in BC

metastasis during an in vivo genome-wide CRISPR screening of

CTCs from patients with hormone receptor positive (HR+)

BC. It was found that RPL15 overexpression was strongly

associated with the metastatic growth of BC in numerous organs of

patients and a poor prognosis. RPL15 gene encodes the 60S

RPL15, which catalyzes protein synthesis (41). A previous study showed that

RPL15 also enhances drug resistance to chemotherapy in

patients with gastric cancer (42);

however, the exact mechanism of RPL15 action in cancer

development remains unclear. It was hypothesized that RPL15

overexpression in CTCs promotes recurrence and metastasis of BC. To

address this hypothesis, the CanPatrol technique was used to detect

RPL15 gene expression in CTCs of patients with BC and

evaluate the relationship between RPL15 expression and

patient outcomes. Therefore, patients with BC were recruited to

measure their CTCs and RPL15 expression before treatment.

The results provide insights into the metastatic mechanisms of BC

and can be helpful for guiding clinical treatment decision.

Materials and methods

Study design and subjects

The present study recruited 170 patients with BC to

evaluate the outcomes of patients with various CTCs levels. Female

patients who were 27-83 years-old and admitted to the Hubei Cancer

Hospital from November 2007 to July 2022 were included in the

present study. The criteria for enrollment were as follows: i) age

>18 years; ii) BC diagnosis confirmed by two independent

clinical pathologists in tumor biopsy or fine-needle aspiration

samples and combined computerized tomography (CT) scan images; iii)

tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stages I-III determined according to

proposal criteria in AACR-8th edition (43); iv) with estrogen receptor (ER),

progesterone receptor (PR) and epidermal growth factor receptor 2

(HER2) expression detected via IHC before surgery; and v) complete

medical data and follow-up record. The following exclusion criteria

were applied to the present study: i) incomplete clinical data; ii)

lost to follow-up; and iii) no previous therapies, such as surgery,

chemotherapy, or radiotherapy before the study. In addition, 10

patients with breast benign nodule were also recruited as a

control. The present study was reviewed and approved (approval no.

2024-264) by the Ethical Committee of the Hubei Cancer Hospital

(Wuhan, China). Written informed consent was obtained from all

patients before the study. The present study was conducted in

accordance with the principles of Declaration of Helsinki (2013

version).

CTCs enrichment and analysis

During EMT transition of CTCs, eCTCs, MCTCs and

HCTCs subtypes can be differentiated using EpCAM and

CK8/18/19 for eCTCs biomarker, Vimentin and

Twist for mesenchymal biomarker measurement. In the present

study, CanPatrol™ technology was utilized to detect

these biomarker-branched DNA (bDNA) (24). Briefly, CTCs were enriched via a

filter-based process, then different CTCs subtypes were identified

using an RNA-ISH technique.

CTCs enrichment was performed as previously

described (19), and none of the

patients received any therapy before the present study. To enrich

CTCs in the peripheral blood of patients with BC, 5 ml of whole

blood was collected from enrolled patients and was transferred into

an EDTA-coated tube one day just before treatment. Blood samples

was immediately processed or stored at 4˚C for <4 h before the

next step. To obtain white blood cells, erythrocytes were mixed

with 15 ml red blood lysis buffer and incubated for 30 min at room

temperature (RT). After centrifugation for 5 min with 300 x g at

RT, the supernatant was discarded. The cells were then washed twice

with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The collected cells were

transferred into a filter tube with 8-µM pore size membrane and

connected with the vacuum filtration system at 0.08 MPa. The

filtered cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 1 h at

RT.

CTCs and RPL15 gene detection using

mRNA probes in RNA-ISH

To evaluate total CTCs and subtypes as well as

RPL15 gene expression in the peripheral blood of patients

with BC, the RNA-ISH technique was employed to detect specific

genes based on the bDNA signal amplification technique because this

technique is more powerful for rare gene expression. The bDNA

signal amplification employs specific capture probes to bind the

target gene sequences and combine bDNA signal amplification probes,

including preamplifier sequence, the amplifier sequences and the

label probes (24,44). The pre-amplifier sequence was

designed to recognize the capture and bDNA amplifier sequences. The

label probes were conjugated with fluorescent dye and counted under

fluorescence scanning microscope (24). Briefly, previous fixed samples were

digested with 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K for 30 min at 4˚C to enhance

the cell membrane permeability. After rinsing twice with PBS

solution, the following capture probes were added to the

hybridization solution and incubated for 2 h at 40˚C: EpCAM

and CK8/18/19 for epithelial biomarker; Vimentin and

Twist for mesenchymal biomarker; RPL15 bDNA probes.

These bDNA specific probes were custom-made and purchased from

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Inc. based on their gene

sequences. To deduce background signals, the cells were washed

twice with 0.1X SSC eluent (MilliporeSigma). Cells were then added

pre-amplification and amplification solution and incubated at 40˚C

for 90 min to obtain a strong signal after adding Alexa Fluor (AF)

594 conjugated EpCAM and CK8/18/19 detection probe, AF488

conjugated Vimentin and Twist probe, and AF750 conjugated

RPL15 probe for 60 min incubation. Finally, DAPI was added

into samples for cellular nucleus staining. Images were obtained

using fluorescence scanning microscope at x100 magnification

(Olympus BX53; Olympus Corporation).

Criteria for CTCs and RPL15 gene

expression positivity

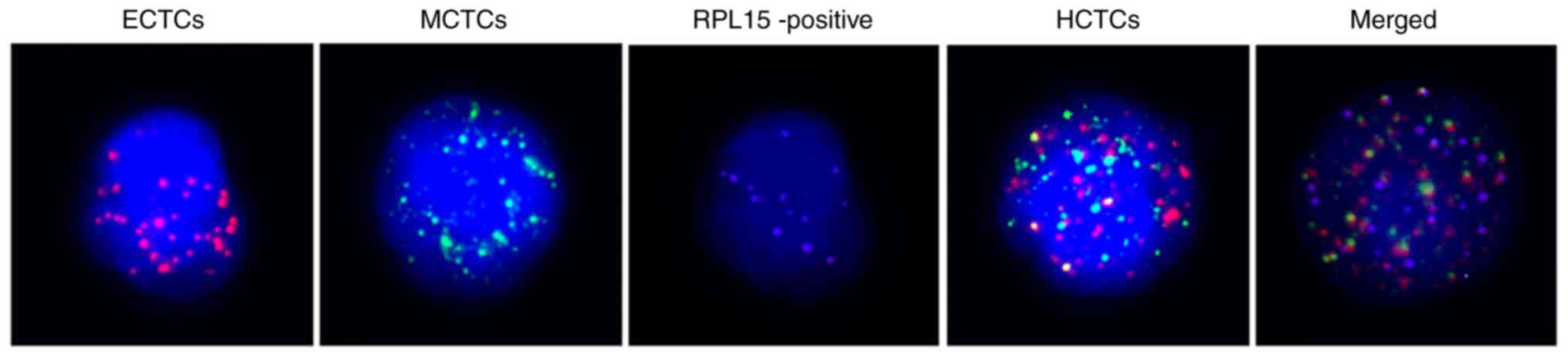

Positive eCTCs, MCTCs, HCTCs, and RPL15 cells

were determined and counted under a fluorescence microscope,

following the manufacturer's instructions (SurExam; http://www.surexam.com). Only red or green

fluorescence signal spots on cell surface represent eCTCs and

MCTCs, respectively. If there were both red and green spots on cell

surface, these cells were classified as HCTCs. The purple

fluorescence signal dots represent RPL15 gene on cellular

surface. The positive RPL15 gene was counted with ≥1 purple

dots/5 ml peripheral blood on CTC, MCTCs, or HCTCs. No any purple

dots on CTCs were observed and defined as RPL15 negative.

Images of 5 microscopy fields were randomly captured and average

number of CTCs in each field was counted. These cell-specific

images and characteristics are presented in Fig. 1 and Table I.

| Table ICTCs and RPL15 classification

features. |

Table I

CTCs and RPL15 classification

features.

| Subtypes | Spot color | DAPI |

|---|

| Epithelial

CTCs | Red | + |

| Mesenchymal

CTCs | Green | + |

| Hybrid CTCs | Red and green | + |

| RPL15+, | Purple | + |

HR detection using IHC and

fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH)

HR expression levels, including ER, PR and HER2,

were detected via IHC for ER and PR or FISH for HER2. Tumor samples

were prepared as 4-µM wide sections and mounted into slides. The

primary antibodies at 1:1,000 dilution were incubated overnight at

4˚C and the secondary antibody at 1:1,000 dilution were incubated

at RT for 1 h according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche

Diagnostics). ER- and PR-positive cells were identified by at least

three certified pathologists. Positive HER2 cells were quantified

using FISH method (Sinomdgene; https://www.sinogenepets.com). Briefly, the

deparaffinized sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor

tissue were incubated with a serial of reagents. HER2 specific DNA

probe labeled with spectrum orange and chromosome enumeration probe

(CEP17) labeled with spectrum green were added to slides for

staining. The cells were observed and counted under a fluorescence

microscope following the 2018 ASCO/CAP criteria (45).

Disease status follow-up

All patients were followed up to 24 months by

visitor phone call by every three months in the first half year,

then every six months thereafter. Follow-up data included disease

symptoms, chest computed tomography (CT), skull magnetic resonance

imaging, whole-body bone scan, abdominal color ultrasound, and

positron emission tomography. Signs of recurrence and metastasis

were determined by image data showing space-occupying lesions in

the chest and other organs. Progression-free survival (PFS) was

defined as time from treatment to recurrence.

Statistical analysis

All data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism

9.0 version (Dotmatics). A comparison of the relationship between

continuous or categorical variables and patient demographics was

performed using the paired t-test and χ2 tests. Cox

proportional hazard regression model were used to investigate the

factors (age, MCTCs, HCTCs, RPL15, ER, PR and HER2)

impacting patients' outcomes. In this model, age, MCTCs, HCTCs,

RPL15, ER, PR and HER2 were as variables and PFS was as

events at 24 months cut-off. Hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence

intervals (CI), and P-values were compared in varous groups. The

assessment of Schoenfeld's residuals was used to ensure the

assumptions have not been violated. The PFS curve of patients was

plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method after the log-rank test. A power

calculation was used to determine differences in PFS of the

subgroups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Patient clinico-pathological

charateristics

All patients were female, and ages ranged from 27-83

years-old (median, 59 years-old; mean ± SD, 50.95±10.76 years-old).

A total of 29 patients were ≥65 years-old (range 61-63) (29/170,

17.1%) and 141 patients were <60 years-old (range 27-60,

141/170, 82.9%). A total of 152 patients had invasive ductal

carcinoma (IDC) (89.4%), and the rest of the study cohort included

3 patients with invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC, 1.8%), 8 with

ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS, 4.8%), 2 with mucinous

carcinoma (MC, 1.1%), 2 with metaplastic carcinoma (MeC, 1.1%) and

3 with papillary carcinoma (PC, 1.8%), r espectively. Regarding

patient TNM stages, 70 were stage I (70/170, 41.2%), 72 were stage

II (72/170, 42.3%), 20 were stage III (20/170, 11.7%), and 8

patients had DCIS (8/170,4.8%) based on criteria recommended by

AACR-8th edition (43). ER, PR and

HER2 were measured using IHC and FISH methods. Regarding

HR+ status, 114 were ER+ (114/170, 67.1%),

105 were PR+ (105/170, 61.8%), 88 were HER2+

(88/170, 51.8%), and 12 triple-negative BC (TNBC, 25/170, 14.7%).

All patients performed surgery, 162 cases (95.3%) of which added

chemotherapy. Additionally, 90 patients (52.9%) experienced

immunotherapy using anti-PD1 administration (Table II).

| Table IIBaseline clinical characteristics of

170 patients with breast cancer. |

Table II

Baseline clinical characteristics of

170 patients with breast cancer.

|

Characteristics | Median | Range | Case number | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Age, years | | | | |

|

≥60 | 65 | 61-83 | 29 | 17.1 |

|

<60 | 49 | 27-60 | 141 | 82.9 |

| Histologic

type | | | | |

|

Invasive

ductal carcinoma | NA | NA | 152 | 89.4 |

|

Invasive

lobular carcinoma | NA | NA | 3 | 1.8 |

|

DCIS | NA | NA | 8 | 4.8 |

|

Papillary

carcinoma | NA | NA | 3 | 1.8 |

|

Metaplastic

carcinoma | NA | NA | 2 | 1.1 |

|

Mucinous

carcinoma | NA | NA | 2 | 1.1 |

|

Tumor-node-metastasis stage | | | | |

|

DCIS | NA | NA | 8 | 4.8 |

|

I | NA | NA | 70 | 41.2 |

|

II | NA | NA | 72 | 42.3 |

|

III | NA | NA | 20 | 11.7 |

| Hormone receptor

positive | | | | |

|

Estrogen

receptor | NA | NA | 114 | 67.1 |

|

Progesterone

receptor | NA | NA | 105 | 61.8 |

|

Epidermal

growth factor receptor 2 | NA | NA | 88 | 51.8 |

|

Triple

negative breast cancer | NA | NA | 25 | 14.7 |

| Therapies | | | | |

|

Surgery | NA | NA | 170 | 100 |

|

Surgery +

chemotherapy | NA | NA | 162 | 95.3 |

|

Surgery +

immunotherapy | NA | NA | 90 | 52.9 |

CTCs and RPL15 expression in patients

with BC

CTCs and RPL15 gene expression are strongly

associated with tumorigenesis and the outcome of patients with BC.

CTCs, CTCs' subtypes and RPL15 expression level in patients

with BC were detected in the present study using CanPatrol

technology combined triple color in situ RNA hybridization

(Table I and Fig. 1). These specific biomarkers possess

unique cellular surface molecules that can be labeled with

differentiated fluorochromes and counted under a fluorescence

microscope. For positive RPL15 expression, CTC, MCTCs, or

HCTCs were firstly counted, then RPL15 gene expression was

calculated on these CTCs. As can be observed in Table III, no significant differences

were found in total CTCs, eCTCs, MCTCs, HCTCs and RPL15 on

TCTCs between patients aged ≥60 years and those <60 years.

Furthermore, the CTCs in patients with different pathological

subtypes, including IDC, ILC, DCIS, PC, MeC and MC, did not

significantly differ. Interestingly, CTCs and RPL15 on the total

CTCs of patients with BC were strongly associated with TNM stage

(P=0.021) and HR levels (P=0.13). Positive CTCs and RPL15 on CTC

rates were significantly increased in advanced TNM. Furthermore,

patients with TNBC had significantly higher CTCs and PRL15

expression than those with other HR types. Recent data have shown

that CTCs and RPL15 expression are significantly associated

with TNM stages and HR expression levels in patients with BC.

| Table IIICTCs and RPL15 prevalence of patients

with breast cancer (170 cases). |

Table III

CTCs and RPL15 prevalence of patients

with breast cancer (170 cases).

|

Characteristics | Total CTCs

(>7/≤7, n %) | Epithelial CTCs

(P/N, n %) | Mesenchymal CTCs

(>2/≤2, n %) | Hybrid CTCs

(>5/≤5, n %) | RPL15 on total CTCs

(P/N, n %) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | | | | | | 0.763 |

|

≥60 | 15 (60.0) | 2(8) | 14(56) | 18(72) | 7 (46.7) | |

|

<60 | 70 (49.6) | 40 (28.3) | 50 (35.5) | 75 (53.2) | 40 (57.1) | |

| Histologic

type | | | | | | 0.384 |

|

Invasive

ductal carcinoma | 50 (32.9) | 60 (39.5) | 70(46) | 55 (36.2) | 40 (26.3) | |

|

Invasive

lobular carcinoma | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | |

|

Ductal

carcinoma in situ | 2(25) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | |

|

Papillary

carcinoma | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | |

|

Metaplastic

carcinoma | 1(50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1(50) | 1(50) | |

|

Mucinous

carcinoma | 1(50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1(50) | 1(50) | |

|

Tumor-node-metastasis stages | | | | | | 0.021 |

|

I | 30 (42.9) | 3 (4.3) | 16 (22.9) | 11 (15.7) | 10 (33.3) | |

|

II | 50 (69.4) | 5 (6.9) | 26 (36.1) | 19 (26.3) | 35 (48.6) | |

|

III | 15(75) | 7(35) | 13(65) | 12(60) | 15(75) | |

| Hormone

receptor | | | | | | 0.013 |

| Estrogen

receptor | 20(18) | 17 (15.3) | 15 (13.5) | 17 (15.3) | 25 (22.5) | |

|

Progesterone

receptor | 23 (22.3) | 20(19) | 23 (21.9) | 25 (23.8) | 30 (28.7) | |

|

Epidermal

growth factor receptor 2 | 13 (14.8) | 21 (23.9) | 31 (35.2) | 29 (32.9) | 35 (39.7) | |

|

Triple-negative

breast cancer | 15(60) | 5(20) | 16(64) | 20(80) | 19(76) | |

The prediction of recurrence and

metastaisis in patients with BCusing multivariate COX regression

analysis

To further evaluate the outcomes of patients with

different clinical characteristics, recurrence and metastasis in

patients were predicted via multivariate COX proportional hazard

regression analysis using age, MCTCs, HCTCs, RPL15 on TCTCs,

ER, PR and HER2 as co-variates. The follow-up time was variable,

and PFS as well as relapse were defined as events. Age, CTC cut-off

values, RPL15, ER, PR, HER2 positive or negative expression were

used as the other variable, and Graphpad Prism softare was used for

statitical analysis. A total of 24 months follow-up was set as

cut-off duration for recurrence,metastasis and PFS time (Table IV). These cut-off values of

biomarker expressive levels in patients with BC were determined

according to RPL15 CTCs and levels of 10 patients with

breast benign nodule, which can distinguish benign and malignant

breast mass with >80% sensitivity and specificity at these

cut-off values. The patients with ≥/<60 years of age,

ER+/- and

PR+/- expression were not

determining factors for recurrenece and metastasis. By contrast,

high MCTCs, HCTCS, positive RPL15 on CTCs had 2.73, 2.38,

1.83 and 2.76 HR for recurrence and metastasis, which mean that

relapse and metastasis chances of patients with high MCTCs (>2),

HCTCs (>5), and positive RPL15 were 2.73,2.38 and

2,76-fold than that of patients with low MCTCs (≤2), HCTCs (≤5) and

negative RPL15, respectively. The PFS of patients

with low MCTCs, low HCTCs, negative RPL15 gene expression and

negative HER2 expression was significantlylonger than that of the

patients with positive expression levels, respectively

(P<0.05).

| Table IVMultivariate analysis of risk factors

for recurrence and metastasis in patients with breast cancer. |

Table IV

Multivariate analysis of risk factors

for recurrence and metastasis in patients with breast cancer.

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence

interval | P-value |

|---|

| Age | 1.004 | 0.978-1.031 | 0.505 |

| Mesenchymal

circulating tumor cells | 2.73 | 1.25-116.9 | 0.014 |

| Hybrid circulating

tumor cells | 2.38 | 2.14-3.27 | 0.027 |

| Ribosomal protein L

15 on circulating tumor cells | 1.83 | 1.87-2.79 | 0.0032 |

| Estrogen

receptor-positive | 1.097 | 0.5456-2.3 | 0.801 |

| Progesterone

receptor-positive | 1.09 | 0.558-2.27 | 0.807 |

| Human epithelial

growth factor receptor 2-positive | 2.76 | 2.83-3.57 | 0.013 |

Survival comparison of patients with

various CTCs, RPL15 and HR expression by Kaplan-Meier analysis

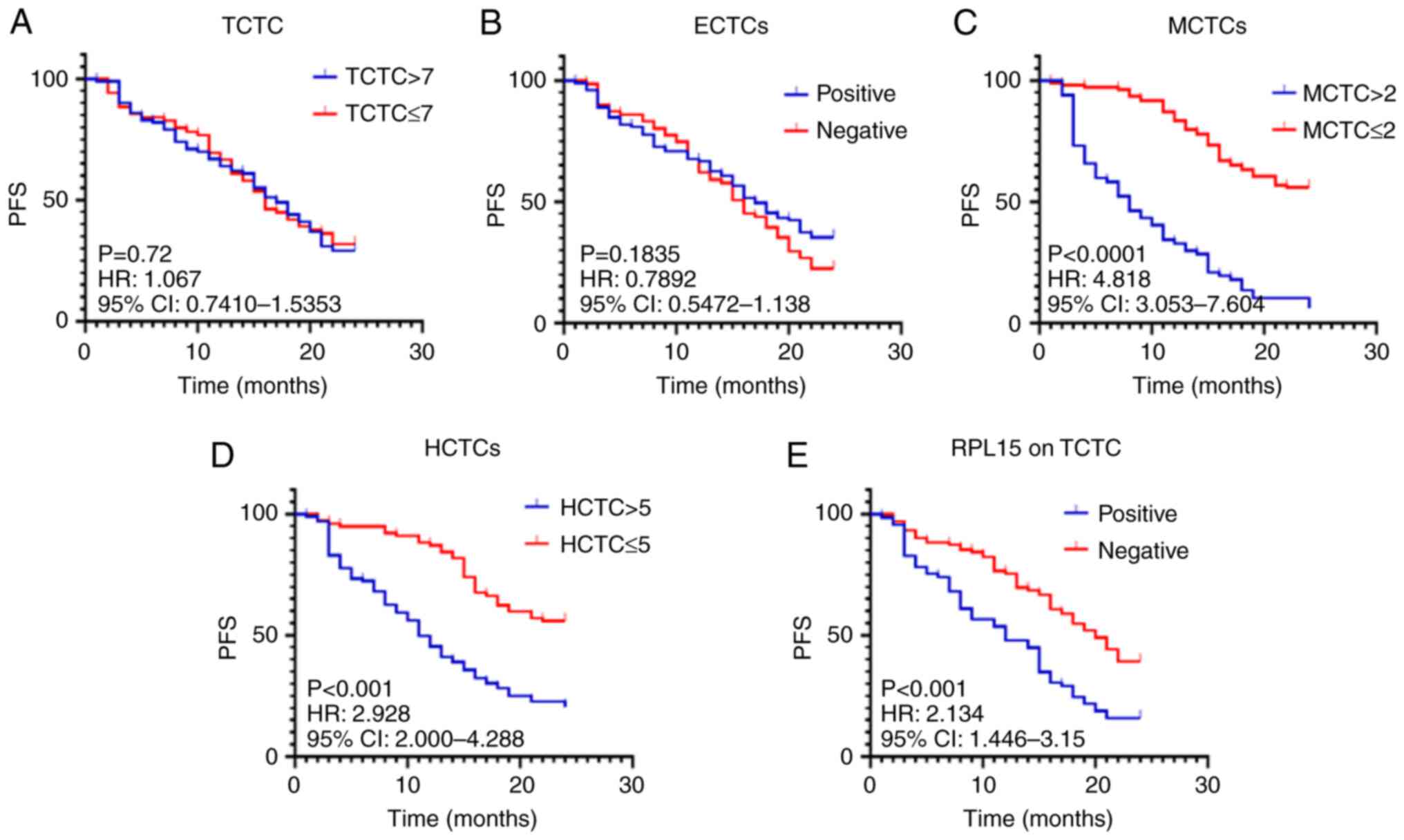

The multivariate COX regress analysis showed that

MCTCs, HCTCs, RPL15 and positive HER2 were critical risk

factors for recurrence and metastasis of patients with BC;a

survival analysis of patient with different CTCs and RPL15

levels was further carried out via a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

(Fig. 2). Different cut-off values

for total CTCs and subtypes were set to compare PFS duration. The

results demonstrated that PFS of patients with >7/≤7 TCTCs

(Fig. 2A), positive/negative eCTCs

(Fig. 2B) did not significatly

differ (P>0.05). By contrast, the PFS of patients with low MCTCs

(Fig. 2C), HCTCs (Fig. 2D) and RPL15 on TCTCs

(Fig. 2E) was significantly longer

than that of patients with high MCTCs, HCTCs, and positive

RPL15 expression. The associated HRs, 95% CIs, and P-value

were: HR, 4.818; 95% CI, 3.053-7.604; P<0.0001 for MCTCs; HR,

2.928; 95% CI, 2-4.288; P<0.001 for HCTCs; HR, 2.134; 95% CI,

1.446-3.15; P<0.001 for RPL15 (Fig. 2 and Table V). These data revealed that high

MCTCs, HCTCs, and positive RPL15 expression on CTCs were

critical risk factors for prognosis of patients with BC.

| Table VSurvival comparison of CTCs and

RPL15 expression in patients with breast cancer. |

Table V

Survival comparison of CTCs and

RPL15 expression in patients with breast cancer.

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence

interval | P-value |

|---|

| TCTCs | 1.067 | 0.741-1.535 | 0.72 |

| Epithelial

CTCs | 0.7892 | 0.5472-1.138 | 0.1835 |

| Mesenchymal

CTCs | 4.818 | 3.053-7.604 | <0.0001 |

| Hybrid CTCs | 2.928 | 2-4.288 | <0.0001 |

| RPL15 on

TCTCs | 2.134 | 1.446-3.15 | <0.0001 |

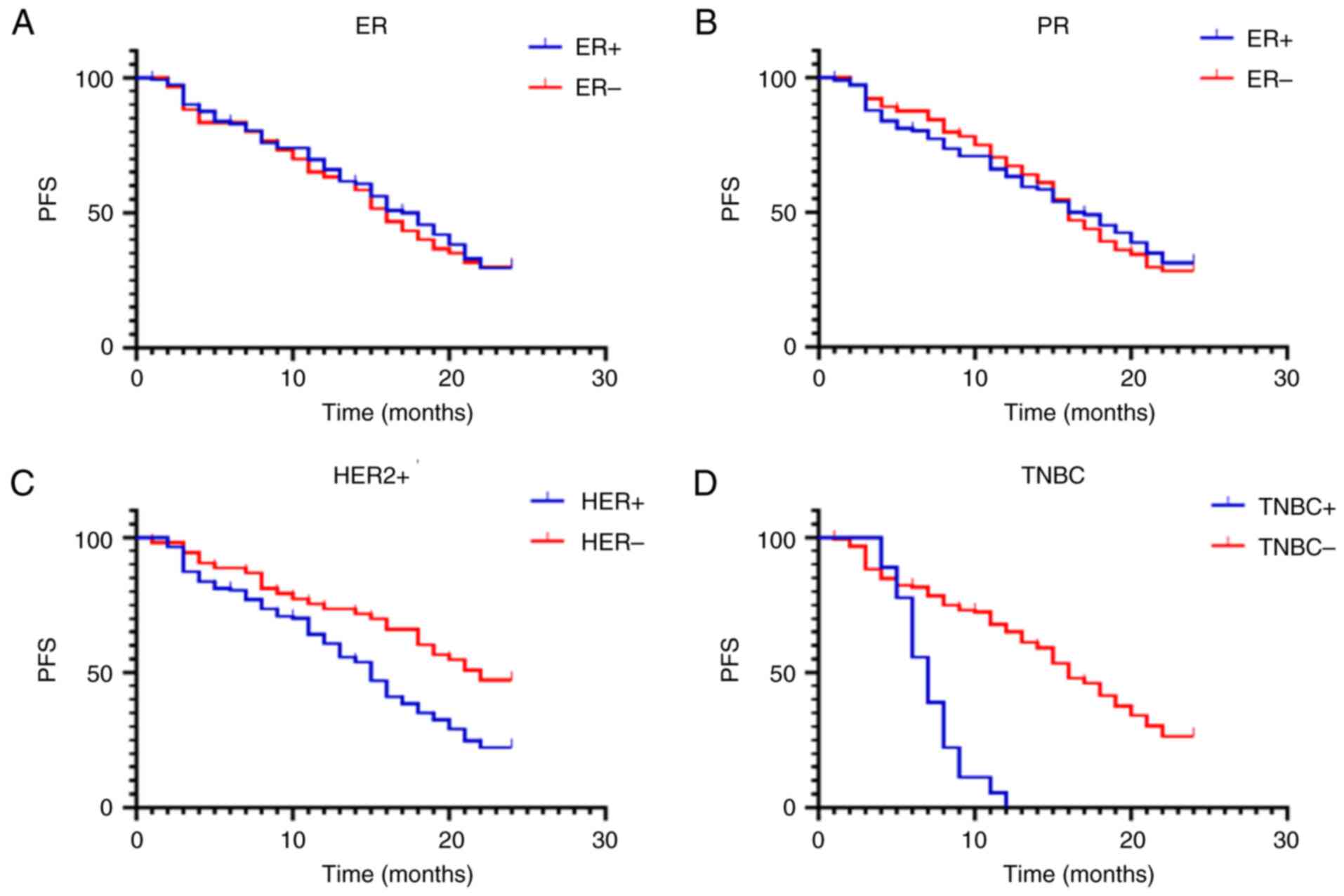

The PFS durations of patients with different HR

expression levels was also compared (Fig. 3 and Table VI). The results identified that PFS

duration of patients with positive and negative ER (Fig. 3A) or PR (Fig. 3B) was not significant differences

(P>0.05). By contrast, the PFS of patients with positive HER2

expression was significantly shorter than that of patients with

negative HER2 (Fig. 3C; HR, 1.929;

95% CI, 1.33-2.797; P=0.0014). The PFS of patients with and without

TNBC were also compared (Fig. 3D),

and the following results were observed: HR, 3.734; 95% CI,

1.573-8.862; P<0.001 (Table

VI).

| Table VISurvival comparison of hormone

receptor expression in patients with breast cancer. |

Table VI

Survival comparison of hormone

receptor expression in patients with breast cancer.

| Variables | | 95% confidence

interval | P-value |

|---|

| Estrogen

receptor-positive | 0.9575 | 0.6558-1.398 | 0.8159 |

| Progesterone

receptor-positive | 0.9578 | 0.6611-1.388 | 0.814 |

| Human epithelial

growth factor receptor 2-positive | 1.929 | 1.33-2.797 | 0.0014 |

| Triple-negative

breast cancer | 3.734 | 1.573-8.862 | <0.0001 |

Discussion

Numerous prior studies have indicated that CTCs are

critical biomarkers for predicting tumor recurrence and metastasis.

Notably, the results of the present study showed that patients with

high MCTCs, HCTCs, RPL15 positivity, and HER2 positivity had

significantly poorer survival times than those without. In

addition, the PFS of patients with TNBC was significanlty shorter

than that of patients without TNBC.

BC is an exceedingly prevalent disease in women and

can frequently recur (46,47). Chemotherapy is a critical

therapeutic option for patients with advanced-stage cancers;

however, the pathologic types of BC are very heterogeneous and

occur in various locations (48).

Most patients eventually experience relapse owing to drug

resistance; therefore, there is an urgent need to identify

sensitive and reliable biomarkers for predicting patient prognosis.

Recently, CTCs have received increasing attention because they have

the same features at the primary and metastatic sites (49), and CTC detection has been

extensively used to predict the outcomes of numerous types of

cancers (19,22,49,50).

CanPatrol combined with RNA-ISH has been utilized to detect CTCs

levels in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and

achieved 81.6% sensitivity and 86.8% specificity at 0.5 CTCs/5 ml

cut-off (19). This technique has

also been used to determine CTCs and programmed cell death-ligand 1

(PD-L1) expression in patients with NSCLC (50). The results indicated high levels of

TCTCs, MCTCs and PD-L1 (+) CTCs levels in patients correlate with

poor survival. The present data are consistent with these findings

and indicate that patients with high levels of MCTCs and HCTCs had

a shorter PFS. Prior results also suggest that the EMT is really

involved in BC tumorigenesis, because MCTCs exhibit greater

invasive ability (51).

Prior studies revealed that CTCs levels were

positively correlated with cancer stage. Dong et al

(50) revealed that OS of patients

with NSCLC at stage III was significantly shorter that those at

stage I-II. Wang et al (52)

indicated that positive CTCs' detection was most likely to occur in

patients with NSCLC at stage IV. Actually, the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) approved CellSearch® system use in

clinical practice in 2004, which measured expression of CTCs in

patients with monitor metastatic BC based on the results of

Cristofanilli et al (23).

The present data showed that CTCs and positive RPL15 of

patients at stage III were significantly higher than those at stage

I-II, indicating that CTCs and RPL15 arereally associated

with BC stage. It was also identified that PFS of patients with

high MCTCs (>2) and HCTCs (>5) was significantly shorter than

those with low MCTCs (≤2) and HCTCs (≤5) (P<0.001), suggesting

that MCTCs may play more crucial roles in EMT transition in

patients with BC. In addition, some positive CTCs and RPL15

were also found at early stage of BC, illustrating early CTCs and

RPL15 detection have great clinical significances. These

results drive physicians to measure CTCs and RPL15

expression and guide optimal treatments before BC treatments.

RPL15 is a subunit of the large ribosomal

complex and is involved in rRNA processing (40). Previous studies showed that high

RPL15 levels are associated with a poor prognosis in

esophageal cancer (53), skin

squamous cell carcinoma (54) and

pancreatic cancer (55).

Furthermore, Shi and Liu (56)

reported that elevated RPL15 expression in patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma was associated with shorter survival

times. The present study showed that the PFS of patients with

positive RPL15 on CTCs was shorter (2.134-fold) than that of

patients with negative RPL15 expression on CTCs. This result

further confirms that RPL15 expression in CTCs is also a key

biomarker for predicting prognosis of patients with BC. Other

studies also revealed that RPL15 is involved in antitumor

immune activation (57,58), indicating that RPL15 plays

crucial roles in occurrence, progression and prognosis of cancer.

Therefore, RPL15 detection may have great benefits for

guiding treatment of patients with BC, which encourages clinicians

to routinely perform these tests to improve evaluation of the

status of patients and predict their prognosis. If RPL15 of

patients is positive on CTCs, chemotherapy, immune therapy and

hormone therapy should be performed as soon as possible after

surgery because these patients have high relapse chances.

The relationship between HR expression and outcome

in patients with BC has been extensively investigated (49,59,60),

and HR expression has been found to strongly associated with the

therapeutic methods used by patients (61,62).

For example, HER2+ patients with Enhertu treatment have

significantly longer survival times than those treated with regular

chemotherapy (61). The outcomes of

BC with HER2+ are poor because HER2 amplification is

closely associated with HER2 protein overexpression, indicating

breast cancer with HER2+ had more invasive ability than

those with HER2- (63).

The present data indicate that HER2+ expression before

treatment strongly associates with the prognosis of patients with

BC, although ER+ and PR+ were not risk

factors for recurrence and metastasis. The PFS of patients with

HER2+ was significantly shorter than those with HER2-,

indicating that targeting HER2 has significant benefits on the

outcomes of patients with BC. Therefore, if HER2 in BC will be

detected before treatment, immediate Enhertu administration may

prolong survival time of patients. In the present study,

HER2+ expression was detected before treatment, and

targeting HER2+ therapy was not adjusted for survival

analysis. This may give rise to bias based on targeting

HER2+ treatment. Further analysis will compare patient

survival rates in the patients with and without targeting

HER2+ therapy.

The present findings are noteworthy; however, the

following observations and limitations should be noted when

interpreting our results: i) CTC number was found to drive BC

tumorigenesis; ii) RPL15 expression was associated with the

prognosis of patients with BC; iii) the sample size patient

subtypes is small, which may have resulted in a selection bias; iv)

the lack of validation of cellular or clinical samples; and v)

sub-analysis of RPL15 on TCTC was unclear. To overcome these

limitations, the authors plan to recruit more patients and perform

additional biological, molecular biology and biochemical

experiments to explore CTC biology in patients with BC. The

prognosis of patients with RPL15-combined MCTCs or HCTCs

will be explored in the future to further understand biological

significance of RPL15. The clinical significances of

sub-analysis of RPL15 on TCTC will undoubtfully have great

benefits for BC survival.

In conclusion, the PFS of patients with >2 MCTC,

>5HCTCs, and positive RPL15expression was shorter than

that of those with ≤2 MCTCs, ≤5 HCTCs, and negative RPL15

expression, and the prognosis of BC patients with negative HER2

expression was favorable, compared with that of patients with

positive HER2 expression.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Health

Commission of Hubei (grant no. WJ2019F190), the Beijing Kangmeng

Charity Federation (grant no. TB212045) and the Administration of

Traditional Chinese Medicine of Hubei (grant no. ZY2023F024).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YZ and WZ contributed to manuscript drafting and the

design of the study. YZ, SSL and WF carried out experiments. YZ,

KS, SSL and HL contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the

data. KS and WF confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was reviewed and approved

(approval no. 2024-264) by the Ethical Committee of Hubei Cancer

Hospital (Wuhan, China). Written informed consent was obtained from

all patients before the study. The present study was conducted in

accordance with the principles of Declaration of Helsinki (2013

version).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Xia C,

Zuo T, Yang Z, Zou X and He J: Cancer incidence and mortality in

China, 2013. Cancer Lett. 401:63–71. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Balasubramanian R, Rolph R, Morgan C and

Hamed H: Genetics of breast cancer: Management strategies and

risk-reducing surgery. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 80:720–725.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 70:7–30. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Laversanne M, Brewster

DH, Gombe Mbalawa C, Kohler B, Piñeros M, Steliarova-Foucher E,

Swaminathan R, Antoni S, et al: Cancer incidence in five

continents: Inclusion criteria, highlights from volume X and the

global status of cancer registration. Int J Cancer. 137:2060–2071.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in

Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative

reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30

countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women

without the disease. Lancet. 360:187–195. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Gage M, Wattendorf D and Henry LR:

Translational advances regarding hereditary breast cancer

syndromes. J Surg Oncol. 105:444–451. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R,

Herzig A, Michaelson JS, Shih YC, Walter LC, Church TR, Flowers CR,

LaMonte SJ, et al: Breast cancer screening for women at average

risk: 2015 Guideline update from the American cancer society. JAMA.

314:1599–1614. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Fleshner L, Lagree A, Shiner A, Alera MA,

Bielecki M, Grant R, Kiss A, Krzyzanowska MK, Cheng I, Tran WT and

Gandhi S: Drivers of emergency department use among oncology

patients in the era of novel cancer therapeutics: A systematic

review. Oncologist. 28:1020–1033. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Egelston CA, Guo W, Yost SE, Ge X, Lee JS,

Frankel PH, Cui Y, Ruel C, Schmolze D, Murga M, et al:

Immunogenicity and efficacy of pembrolizumab and doxorubicin in a

phase I trial for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast

cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 72:3013–3027. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhao J, Li GY, Lu XY, Zhu LR and Gao Q:

Landscape of m6A RNA methylation regulators in liver

cancer and its therapeutic implications. Front Pharmacol.

15(1376005)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Du C, Wu X, He M, Zhang Y, Zhang R and

Dong CM: Polymeric photothermal agents for cancer therapy: Recent

progress and clinical potential. J Mater Chem B. 9:1478–1490.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kumar V, Garg V and Dureja H:

Nanomedicine-based approaches for delivery of herbal compounds.

Tradit Med Res. 7(48)2022.

|

|

14

|

Gao Z, Zheng S, Kamei K and Tian C: Recent

progress in cancer therapy based on the combination of ferroptosis

with photodynamic therapy. Acta Mater Med. 1:411–426. 2022.

|

|

15

|

Huober J and Thurlimann B: The role of

combination chemotherapy in the treatment of patients with

metastatic breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel). 4:367–372.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Cohen EN, Jayachandran G, Moore RG,

Cristofanilli M, Lang JE, Khoury JD, Press MF, Kim KK, Khazan N,

Zhang Q, et al: A multi-center clinical study to harvest and

characterize circulating tumor cells from patients with metastatic

breast cancer using the Parsortix® PC1 system. Cancers

(Basel). 14(5238)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yu M, Bardia A, Wittner BS, Stott SL, Smas

ME, Ting DT, Isakoff SJ, Ciciliano JC, Wells MN, Shah AM, et al:

Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in

epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science. 339:580–584.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Fina E: Signatures of breast cancer

progression in the blood: What could be learned from circulating

tumor cell transcriptomes. Cancers (Basel). 14(5668)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li J, Liao Y, Ran Y, Wang G, Wu W, Qiu Y,

Liu J, Wen N, Jing T, Wang H and Zhang S: Evaluation of sensitivity

and specificity of CanPatrol™ technology for detection

of circulating tumor cells in patients with non-small cell lung

cance. BMC Pulm Med. 20(274)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ho KH, Huang TW, Shih CM, Lee YT, Liu AJ,

Chen PH and Chen KC: Glycolysis-associated lncRNAs identify a

subgroup of cancer patients with poor prognoses and a

high-infiltration immune microenvironment. BMC Med.

19(59)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Lu H, Li Z, Liu L, Tao Y, Zhou Y, Mao X,

Zhu A, Wu H and Zheng X: A pan-cancer analysis of the oncogenic

roles of RAD51 in human tumors. Adv Gut Microbiome Res.

2022(1591377)2022.

|

|

22

|

Mäurer M, Schott D, Pizon M, Drozdz S,

Wendt T, Wittig A and Pachmann K: Increased circulating epithelial

tumor cells (CETC/CTC) over the course of adjuvant radiotherapy is

a predictor of less favorable outcome in patients with early-stage

breast cancer. Curr Oncol. 30:261–273. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ,

Stopeck A, Matera J, Miller MC, Reuben JM, Doyle GV, Allard WJ,

Terstappen LW and Hayes DF: Circulating tumor cells, disease

progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J

Med. 351:781–791. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wu S, Liu S, Liu Z, Huang J, Pu X, Li J,

Yang D, Deng H, Yang N and Xu J: Classification of circulating

tumor cells by epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers. PLoS One.

10(e0123976)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Jung R, Krüger W, Hosch S, Holweg M,

Kröger N, Gutensohn K, Wagener C, Neumaier M and Zander AR:

Specificity of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

assays designed for the detection of circulating cancer cells is

influenced by cytokines in vivo and in vitro. Br J Cancer.

78:1194–1198. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Giuliano M, Giordano A, Jackson S, Hess

KR, De Giorgi U, Mego M, Handy BC, Ueno NT, Alvarez RH, De

Laurentiis M, et al: Circulating tumor cells as prognostic and

predictive markers in metastatic breast cancer patients receiving

first-line systemic treatment. Breast Cancer Res.

13(R67)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Mego M, Cierna Z, Janega P, Karaba M,

Minarik G, Benca J, Sedlácková T, Sieberova G, Gronesova P,

Manasova D, et al: Relationship between circulating tumor cells and

epithelial to mesenchymal transition in early breast cancer. BMC

Cancer. 15(533)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Mancheng AD and Ossas U: How does lncrna

regulation impact cancer metastasis. Cancer Insight. 1(6)2022.

|

|

29

|

Riethdorf S, Fritsche H, Müller V, Rau T,

Schindlbeck C, Rack B, Janni W, Coith C, Beck K, Jänicke F, et al:

Detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of

patients with metastatic breast cancer: A validation study of the

CellSearch system. Clin Cancer Res. 13:920–928. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Balic M, Dandachi N, Hofmann G, Samonigg

H, Loibner H, Obwaller A, van der Kooi A, Tibbe AG, Doyle GV,

Terstappen LW and Bauernhofer T: Comparison of two methods for

enumerating circulating tumor cells in carcinoma patients.

Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 68:25–30. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Cruz I, Ciudad J, Cruz JJ, Ramos M,

Gómez-Alonso A, Adansa JC, Rodríguez C and Orfao A: Evaluation of

multiparameter flow cytometry for the detection of breast cancer

tumor cells in blood samples. Am J Clin Pathol. 123:66–74.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Meng S, Tripathy D, Frenkel EP, Shete S,

Naftalis EZ, Huth JF, Beitsch PD, Leitch M, Hoover S, Euhus D, et

al: Circulating tumor cells in patients with breast cancer

dormancy. Clin Cancer Res. 10:8152–8162. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yang J, Ma J, Jin Y, Cheng S, Huang S,

Zhang N and Wang Y: Development and validation for prognostic

nomogram of epithelial ovarian cancer recurrence based on

circulating tumor cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Sci

Rep. 11(6540)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zhou H, Shen H, Xiang F, Yang X, Li R,

Zeng Y and Liu Z: Correlation analysis of the expression of

mesenchymal circulating tumor cells and CD133 with the prognosis of

colorectal cancer. Am J Transl Res. 15:3489–3499. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Rath B, Plangger A, Klameth L, Hochmair M,

Ulsperger E, Boeckx B, Neumayer C and Hamilton G: Small cell lung

cancer: Circulating tumor cell lines and expression of mediators of

angiogenesis and coagulation. Explor Target Antitumor Ther.

4:355–365. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Magri V, Marino L, Nicolazzo C, Gradilone

A, De Renzi G, De Meo M, Gandini O, Sabatini A, Santini D, Cortesi

E and Gazzaniga P: Prognostic role of circulating tumor cell

trajectories in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cells.

12(1172)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Chen H, Li H, Shi W, Qin H and Zheng L:

The roles of m6A RNA methylation modification in cancer stem cells:

New opportunities for cancer suppression. Cancer Insight.

1(10)2022.

|

|

38

|

Gao T, Mao J, Huang J, Luo F, Lin L, Lian

Y, Bin S, Zhao L and Li S: Prognostic significance of circulating

tumor cell measurement in the peripheral blood of patients with

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clinics (Sao Paulo).

78(100179)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Wang HT, Bai LY, Wang YT, Lin HJ, Yang HR,

Hsueh PR and Cho DY: Circulating tumor cells positivity provides an

early detection of recurrence of pancreatic cancer. J Formos Med

Assoc. 122:653–655. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Ebright RY, Lee S, Wittner BS,

Niederhoffer KL, Nicholson BT, Bardia A, Truesdell S, Wiley DF,

Wesley B, Li S, et al: Deregulation of ribosomal protein expression

and translation promotes breast cancer metastasis. Science.

367:1468–1473. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Kenmochi N, Kawaguchi T, Rozen S, Davis E,

Goodman N, Hudson TJ, Tanaka T and Page DC: A map of 75 human

ribosomal protein genes. Genome Res. 8:509–523. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Ma Y, Xue H, Wang W, Yuan Y and Liang F:

The miR-567/RPL15/TGF-β/Smad axis inhibits the stem-like properties

and chemo-resistance of gastric cancer cells. Transl Cancer Res.

9:3539–3549. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL and Brierley

JD: AJCC cancer staging manual. 8th edition. New York: Springer,

2017.

|

|

44

|

Tsongalis GJ: Branched DNA technology in

molecular diagnostics. Am J Clin Pathol. 126:448–453.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Allison KH, Harvey

BE, Mangu PB, Bartlett JMS, Bilous M, Ellis IO, Fitzgibbons P,

Hanna W, et al: Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in

breast cancer: American society of clinical oncology/college of

American pathologists clinical practice guideline focused update. J

Clin Oncol. 36:2105–2122. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Joseph C, Papadaki A, Althobiti M,

Alsaleem M, Aleskandarany MA and Rakha EA: Breast cancer

intratumour heterogeneity: Current status and clinical

implications. Histopathology. 73:717–731. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Ji X, Tian X, Feng S, Zhang L, Wang J, Guo

R, Zhu Y, Yu X, Zhang Y, Du H, et al: Intermittent F-actin

perturbations by magnetic fields inhibit breast cancer metastasis.

Research (Wash DC). 6(0080)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Navin N, Krasnitz A, Rodgers L, Cook K,

Meth J, Kendall J, Riggs M, Eberling Y, Troge J, Grubor V, et al:

Inferring tumor progression from genomic heterogeneity. Genome Res.

20:68–80. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Li Y, Jiang X, Zhong M, Yu B and Yuan H:

Whole genome sequencing of single-circulating tumor cell

ameliorates unraveling breast cancer heterogeneity. Breast Cancer

(Dove Med Press). 14:505–513. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Dong J, Zhu D, Tang X, Qiu X, Lu D, Li B,

Lin D and Zhou Q: Detection of circulating tumor cell molecular

subtype in pulmonary vein predicting prognosis of stage I-III

non-small cell lung cancer patients. Front Oncol.

9(1139)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Polyak K and Weinberg RA: Transitions

between epithelial and mesenchymal states: Acquisition of malignant

and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 9:265–273. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Wang X, Ma K, Yang Z, Cui J, He H, Hoffman

AR, Hu JF and Li W: Systematic correlation analyses of circulating

tumor cells with clinical variables and tumor markers in lung

cancer patients. J Cancer. 8:3099–3104. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wang Q, Yang C, Zhou J, Wang X, Wu M and

Liu Z: Cloning and characterization of full-length human ribosomal

protein L15 cDNA which was overexpressed in esophageal cancer.

Gene. 263:205–209. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Nindl I, Dang C, Forschner T, Kuban RJ,

Meyer T, Sterry W and Stockfleth E: Identification of

differentially expressed genes in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

by microarray expression profiling. Mol Cancer.

5(30)2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Yan TT, Fu XL, Li J, Bian YN, Liu DJ, Hua

R, Ren LL, Li CT, Sun YW, Chen HY, et al: Downregulation of RPL15

may predict poor survival and associate with tumor progression in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 6:37028–37042.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Shi R and Liu Z: RPL15 promotes

hepatocellular carcinoma progression via regulation of RPs-MDM2-p53

signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 22(150)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Kitai Y: Elucidation of the mechanism of

topotecan-induced antitumor immune activation. Yakugaku Zasshi.

142:911–916. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Japanese).

|

|

58

|

Yamada S, Kitai Y, Tadokoro T, Takahashi

R, Shoji H, Maemoto T, Ishiura M, Muromoto R, Kashiwakura JI, Ishii

KJ, et al: Identification of RPL15 60S ribosomal protein as a novel

topotecan target protein that correlates with DAMP secretion and

antitumor immune activation. J Immunol. 209:171–179.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Feng H, Liu H, Wang Q, Song M, Yang T,

Zheng L, Wu D, Shao X and Shi G: Breast cancer diagnosis and

prognosis using a high b-value non-Gaussian continuous-time

random-walk model. Clin Radiol. 78:e660–e667. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Mai N, Abuhadra N and Jhaveri K:

Molecularly targeted therapies for triple negative breast cancer:

History, advances, and future directions. Clin Breast Cancer.

23:784–799. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Bartsch R and Bergen E: ASCO 2018:

Highlights in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Memo.

11:280–283. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Papadaki MA, Stoupis G, Theodoropoulos PA,

Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V and Agelaki S: Circulating tumor cells

with stemness and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition features are

chemoresistant and predictive of poor outcome in metastatic breast

cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 18:437–447. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Ahn S, Woo JW, Lee K and Park SY: HER2

status in breast cancer: Changes in guidelines and complicating

factors for interpretation. J Pathol Transl Med. 54:34–44.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|