Introduction

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)

is a transcription factor that controls multiple cellular metabolic

processes and is a member of the nuclear hormone receptor protein

family involved in the regulation of multiple physiological and

pathological metabolic processes, such as lipid and glucose

metabolism regulation in vivo and inflammation regulation

(1). PPARγ is mainly expressed in

monocytes/macrophages and fat cells, and low levels of PPARγ can be

detected in the central nervous system. Recent studies have

revealed that brain ischemic injury promoted the expression and

activity of PPARγ (2) and that a

PPARγ agonist can protect against brain ischemic injury through

PPARγ activation (3,4).

12/15-lipoxygenase (12/15-LOX) is a fatty acid

dioxygenase that can oxidize arachidonic acid into

12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE) in mammalian cells. In

vitro studies of non-neuronal cells revealed that 12-HETE can

activate PPARγ (5). However, no

studies have explored the influence of the 12/15-LOX pathway and

12-HETE on PPARγ activity in neurons damaged by ischemic injury.

The present study investigated the changes in 12/15-LOX and 12-HETE

levels and their impact on PPARγ activation in rat cortical neurons

treated with oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD). Simultaneously,

antisense oligonucleotide technology was used to explore the

influence of 12/15-LOX inhibition on PPARγ expression and

activation to investigate the regulatory effect of 12/15-LOX

pathway on PPARγ. The aim of the present study was to understand

these mechanisms. The results may assist in the understanding of

brain ischemic injury and help develop treatments in the

future.

Materials and methods

Animal grouping and drug

administration

All the animal experiments were carried out

according to an institutionally approved protocol, in accordance

with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use

of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of Tianjin Medical University

(Tianjin, China). Healthy adult male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats

weighing 280–330 g were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center

at the Academy of Military Medical Sciences. All the rats consumed

water freely but were fasted for 12 h before surgery. The rats were

randomly allocated into three groups and were treated as follows:

i) 12 rats in the sham-operation group were used for brain tissue

homogenates for further analysis. ii) 6 rats in the

ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) group were used for tissue sections and

12 rats were used for brain tissue homogenates for further

analysis. iii) 12 rats in the I/R intervention group were used for

brain tissue homogenates. 12-HETE was purchased from Cayman

Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and dissolved in

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 1 mg/ml. In the I/R intervention

group, rats received stereotactic injections of 15 ml 12-HETE 30

min before ischemia induction, whereas the rats in the

sham-operation group or I/R group received equal volumes of

PBS.

Stereotactic intracerebroventricular

injection

Rats were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate 30

min before the establishment of the middle cerebral artery

occlusion/reperfusion (MCAO/R) model. Subsequently, 15 ml 12-HETE

or an equal volume of PBS was injected into the right lateral

ventricle at 0.8 mm posterior to bregma, 1.3 mm right lateral to

midline and 3.5 mm deep into the subdural surface. Injection was

performed at a rate of 1 μl/min and finished in 15 min. The needle

was retained for 15 min and withdrawn at a rate of 1 mm/min to

prevent overflowing of 12-HETE or PBS.

Establishment of MCAO/R model

The rat cerebral artery was occluded with thread for

60 min and reperfusion was performed for 24 h. In the

sham-operation group the common carotid, external carotid and

internal carotid arteries were exposed and separated by surgery

without occlusion.

Primary culture of fetal rat cortical

neurons and neuronal cell identification

Day 18–21 embryonic Sprague Dawley (SD) rats were

sacrificed following anesthesia with ice and 75% ethanol and the

cerebral cortex was isolated under sterile conditions. Pia mater

and blood vessels were removed under a dissecting microscope. The

cerebral cortex were cut into pieces and digested with 0.125%

trypsin at 37°C for 20 min. Subsequently, 20% fetal bovine serum

(FBS) was added to stop digestion and the cells were triturated

with a Pasteur pipette and filtered with a 200-mesh cell strainer

to collect single-cell suspensions. The cells were counted with a

hemocytometer. Cells were seeded into Petri dishes were pre-coated

with 0.1 mg/ml L-polylysine at a final density of

105–106/ml. Primary cortical neurons were

incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere and

high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/nutrient mixture

F-12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 10% horse serum, 1% glutamine and

1% penicillin-streptomycin was used as culture medium. The medium

was changed to neurobasal medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies,

Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 2% B27 following cell

attachment (3 to 6 h after seeding). Half the volume of neurobasal

medium was refreshed every third day. Neuronal-specific marker

microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) was stained at day 9 and

>95% cells were MAP2 positive.

Preparation of the neuronal model of

oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) and 12-HETE or 12/15-LOX antisense

oligonucleotide (asON-12/15-LOX) treatment

Day 9 cortical neurons were randomly divided into

the control, OGD-treated and intervention groups. The medium of the

OGD-treated neurons was changed to neurobasal medium without

glucose (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and the neurons were

incubated in a pre-adjusted tri-gas incubator (37°C, 95%

N2, 5% CO2, <1% O2). After 3 h

incubation, neurons were cultured in the normal medium at the

normal conditions for 24 h and were collected for further analysis.

The 12-HETE intervention group was treated with 1 μM 12-HETE 30 min

before OGD treatment and the 12-HETE concentration was maintained

during the whole culture process. The asON-12/15-LOX intervention

group was treated with 4 μM asON 48 h before OGD treatment and

maintained during the whole culture process. The same volume of

dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added into the OGD-treated group. The

sequences of the antisense oligonucleotides used in the study are

as follows: Antisense, 5′-CTC-AGG-AGG-GTG-TAA-ACA-3′ (6); sense, 5′-TGT-TTA-CAC-CCT-CCT-GAG-3′;

and scramble, 5′-AAG-ATT-GCG-GCG-CGA-CGA-TGA-3′.

Analysis of relative OGD-treated neuron

survival rate by 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl

tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

Cortical neurons at day 9 were divided into 8

replicate blank groups (culture medium without neurons), control

groups and OGD-treated groups. After treatment with OGD for 24 h,

neurons were further cultured in normal medium and medium only was

added into blank wells. Subsequently, 20 μl 5 mg/ml MTT was added

into each well and incubated for 4 h. After discarding the medium,

100 μl DMSO was added, mixed thoroughly and incubated at 37°C for

15 min. The optical density (OD) of each well was analyzed with an

automatic plate reader and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured.

The relative cell survival rate was calculated as follows: Relative

cell survival rate = (OD OGD-treated group − OD blank group)/(OD

control group − OD blank group). The median concentration was used

for the model set.

Nuclear protein extraction

Nuclear proteins were isolated with a nuclear

protein extraction kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according

to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blotting

The primary antibodies were as follows: Mouse

anti-rat PPARγ monoclonal antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz, Dallas,

USA), rabbit anti-rat 12/15-LOX monoclonal antibody (1:1000; Cayman

Chemical Co.); and related horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated

secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX,

USA; 1:5000) were used as previously described (2).

ELISA analysis

The level of 12-HETE in neurons was determined with

the 12-HETE ELISA kit (Assay Design, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and

performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Total RNA isolation and reverse

transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) amplification

Total RNA was extracted from the cells with TRIzol

(Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), precipitated with

chloroform-isopropanol and quantified with absorbance at

OD260. cDNA was generated from 1.5 μg total RNA. PCR

amplification was performed using a 20 μl reaction system,

including 1 μl cDNA, 2 μl forward and reverse primers (5 μM), 200

μM dNTPs and 0.8 U Taq polymerase. Primers for lipoprotein lipase

(LPL) were as follows: Forward,

5′-TTCCATTACCAAGTCAAGATTCAC-3′; and reverse,

5′-TCAGCCCGACTTCTTCAGAGACTT-3′. PCR amplification products were

analyzed with 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis and a gel imaging

system (Tanon Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China)

was used to quantify the band density. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control.

Construction of PGL3-PPRE and

determination of luciferase activity

pGL3-basic (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used as

the vector, which contains the luciferase mRNAs without promoter.

Three peroxisome proliferator responsive element (PPRE) fragments

were inserted upstream of the luciferase gene in the pGL3-basic

vector to construct the pGL3-PPRE vector. Neurons were transfected

with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and 24 h

later, 1 μM 12-HETE was added, whereas in the control group, the

same volume of DMSO was added. The cells were lysed 24 h later and

luciferase analysis was performed according to the instructions of

the luciferase assay system kit (Promega). A Safire2 basic plate

reader from Tecan Australia Pty Ltd. (Melbourne, Australia) was

used to measure the ODs of the cell lysates. The β-galactosidase

enzyme assay system kit (Promega) was used to measure the β-gal

activity to adjust the luciferase value for transfection

efficiency. Adjusted fluorescence value = measured fluorescence

value/β-gal value.

Immunofluorescence staining

Neurons were cultured on sterile slides precoated

with poly-L-lysine. To perform immunofluorescence staining, neurons

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and blocked with serum for 30

min. Neurons were then incubated with a rabbit anti-rat 12/15-LOX

polyclonal antibody (1:100; Cayman Chemical Co.) or anti-PPARγ

antibody (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at 4°C overnight. A

tetraethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody

was added the next day and incubated in the dark at 37°C for 1 h.

Neurons were washed with PBS-Tween 20 and finally incubated with

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole at room temperature for 10 min to

stain the cell nuclei. Slides were treated with mounting medium and

analyzed with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope and Nikon DS-Ril

camera (Nikon, Toyko, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Experimental data was exhibited as mean ± standard

deviation. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 15.0

statistical package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and an independent

samples t test was performed for comparison between groups.

A χ2 test was used to analyze the difference in neuron

survival rates between groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference.

Results

Elevation of 12/15-LOX expression and

activity induced by I/R injury

Western blots were performed to analyze the

expression of 12/15-LOX in rat brain tissues from the I/R injury

model. Significant upregulation of 12/15-LOX expression was induced

by I/R injury (Fig. 1A). To

explore the activity changes of 12/15-LOX, the level of its

product, 12-HETE, was determined by ELISA and the results showed

that I/R injury clearly induced the production of 12-HETE (Fig. 1B).

Induction of PPARγ expression by I/R

injury and further upregulation of PPARγ expression with 12-HETE

intervention

Western blotting showed that compared to the I/R

group, I/R injury plus 12-HETE intervention markedly upregulated

the expression of PPARγ (Fig.

2).

Suppression of inducible nitric oxide

synthase (iNOS) expression by 12-HETE in rat brain tissues with I/R

injury

Western blots were performed to explore the

influence of 12-HETE intervention on iNOS expression and revealed

an evident inhibition of iNOS expression (Fig. 3).

Upregulation of 12/15-LOX expression and

12-HETE generation by OGD treatment in neurons

The MTT assay revealed that the relative neuron

survival rate decreased by 43.84±2.07% with OGD treatment for 24 h

compared to the control group. The difference between the two

groups was significant (P<0.05).

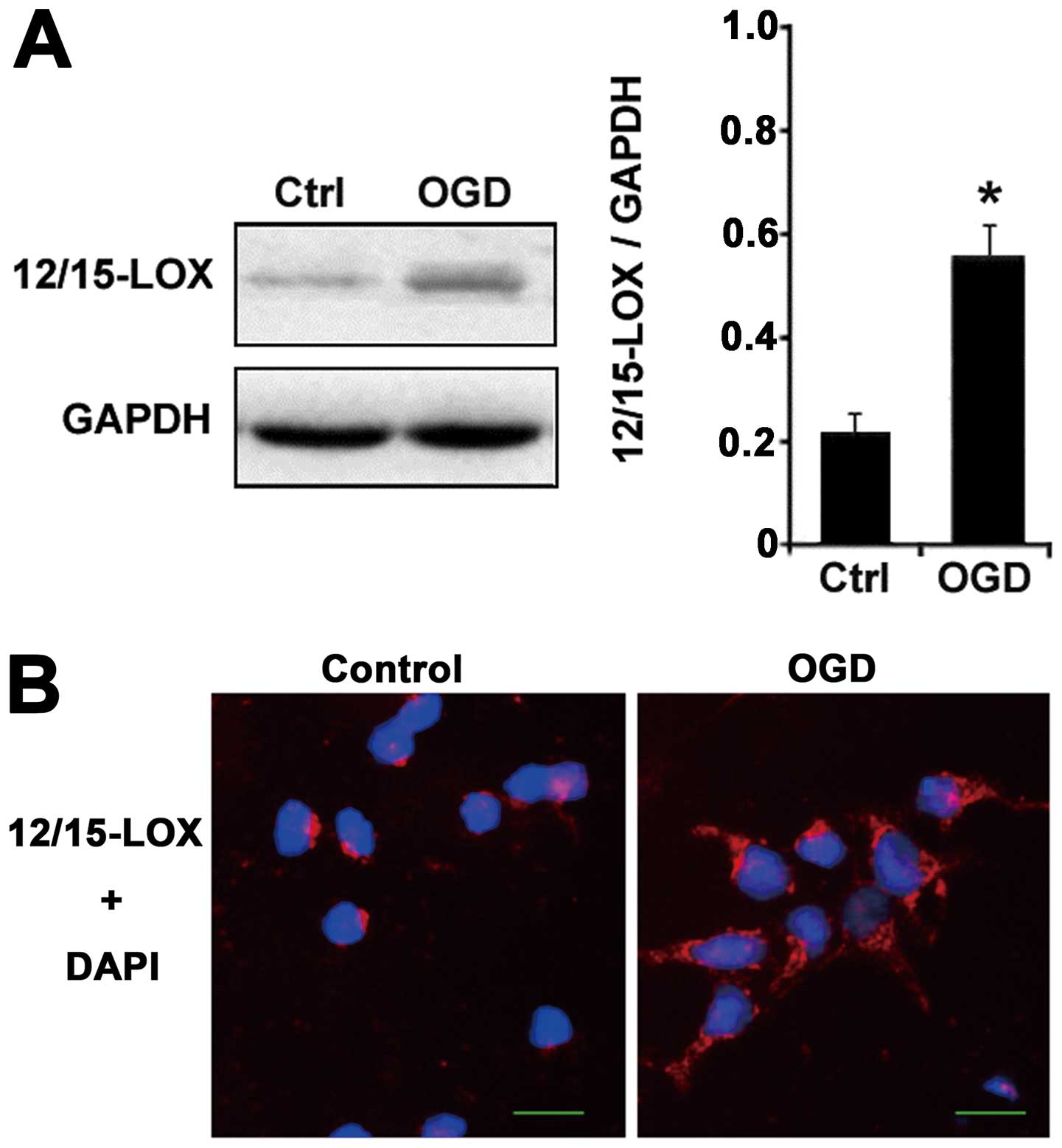

Western blots showed that the 12/15-LOX protein, the

critical enzyme generating 12-HETE, increased significantly with

OGD treatment compared with the control group (Fig. 4A) and immunofluorescence

experiments confirmed that the upregulation of 12/15-LOX expression

was induced by OGD (Fig. 4B).

Stimulation of PPARγ nuclear protein

expression by OGD treatment in neurons and upregulation of PPARγ

nuclear protein expression by 12-HETE in OGD-treated neurons

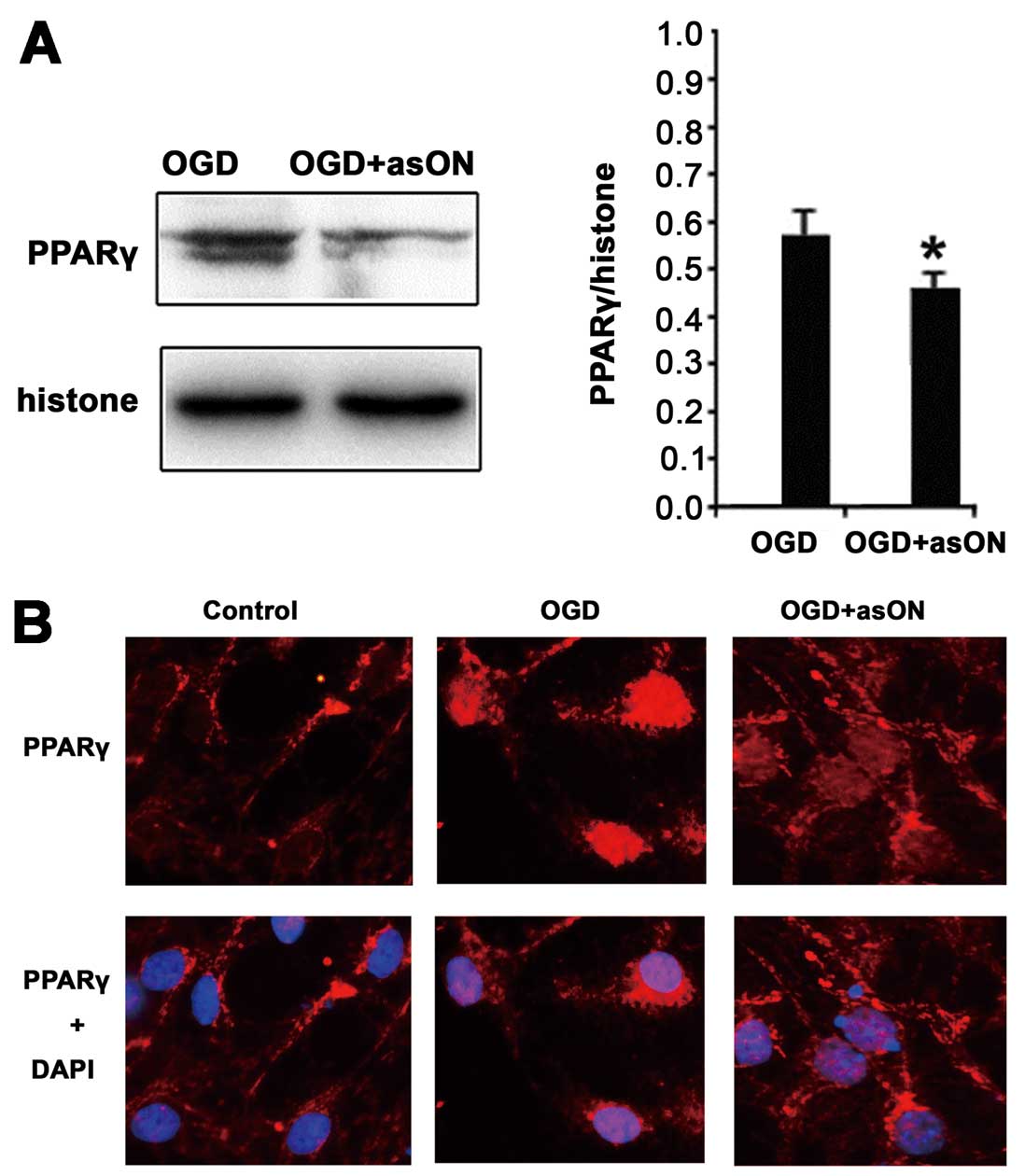

Western blotting was used to determine the

expression levels of PPARγ in the cell nucleus, and the results

showed that PPARγ nuclear protein increased significantly in

neurons with OGD treatment. PPARγ nuclear protein was also

significantly elevated in the 12-HETE intervention plus OGD-treated

group compared to the OGD-treated group (Fig. 5).

Blockade of 12/15-LOX expression by

asON-12/15-LOX treatment in OGD-treated neurons

Compared to the OGD-treated group, asON-12/15-LOX

treatment reduced the expression of 12/15-LOX significantly

(Fig. 6). Whereas sense

oligonucleotides or scramble oligonucleotides of 12/15-LOX did not

change the expression of 12/15-LOX (data not shown).

Inhibition of PPARγ nuclear protein

expression by asON-12/15-LOX treatment in OGD-treated neurons

asON-12/15-LOX treatment inhibited the expression of

PPARγ nuclear protein significantly compared to the OGD-treated

group (Fig. 7A).

Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed the results of the western

blot, showing that the expression of PPARγ nuclear protein was

upregulated with OGD treatment and the upregulation was inhibited

by asON-12/15-LOX treatment (Fig.

7B).

Expression of PPARγ target genes by

12-HETE treatment and suppression of PPARγ target genes by

asON-12/15-LOX treatment in OGD-treated neurons

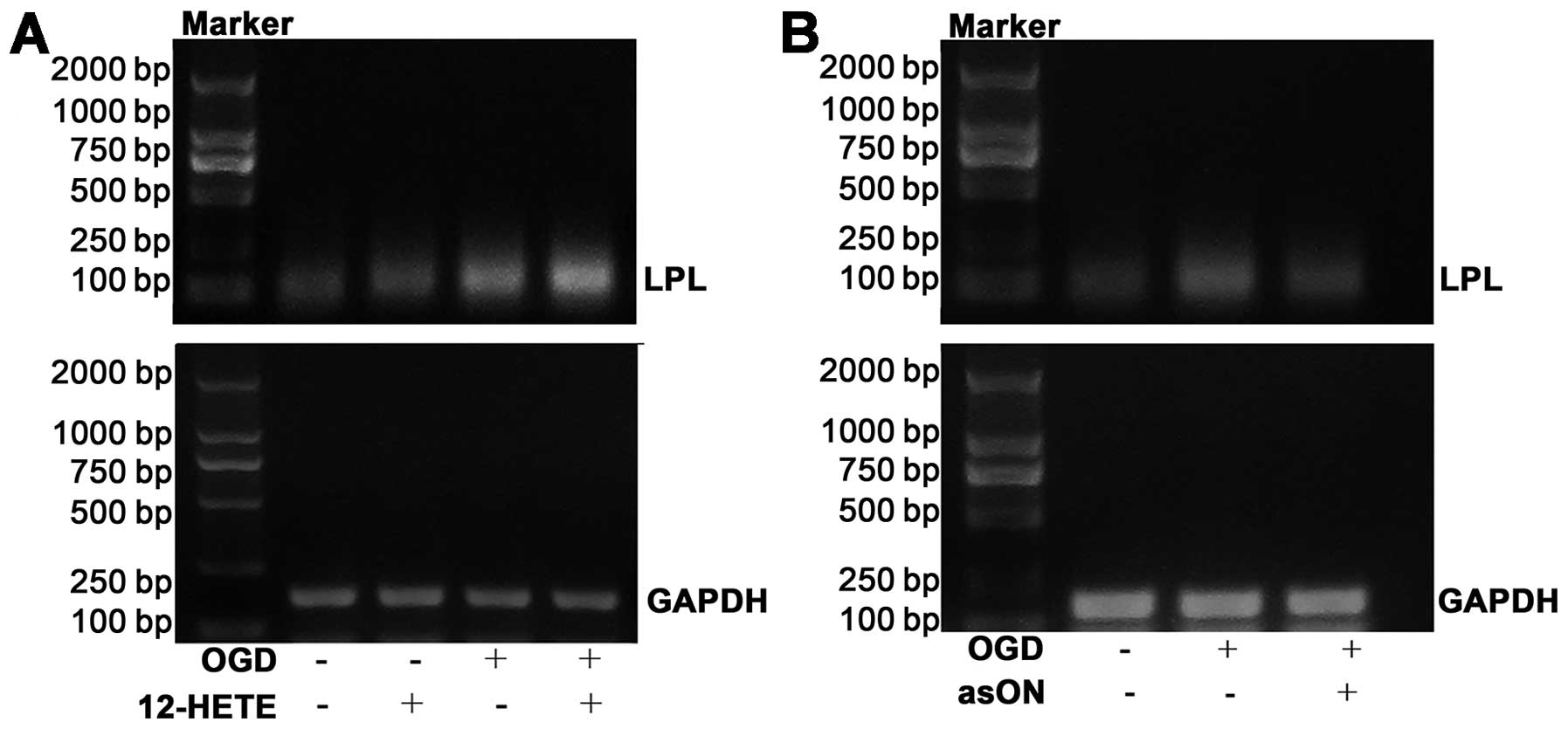

RT-PCR was employed to analyze the expression of

LPL, a PPARγ target gene, in OGD-treated neurons and to

explore the impact of 12-HETE intervention on its expression. The

results showed that 12-HETE intervention markedly increased the

expression of LPL mRNA compared to OGD-treated neurons

(Fig. 8A). However, treatment

with asON-12/15-LOX clearly inhibited the expression of LPL

in OGD-treated neurons (Fig.

8B).

Enhancement of PPARγ binding ability to

DNA by 12-HETE treatment

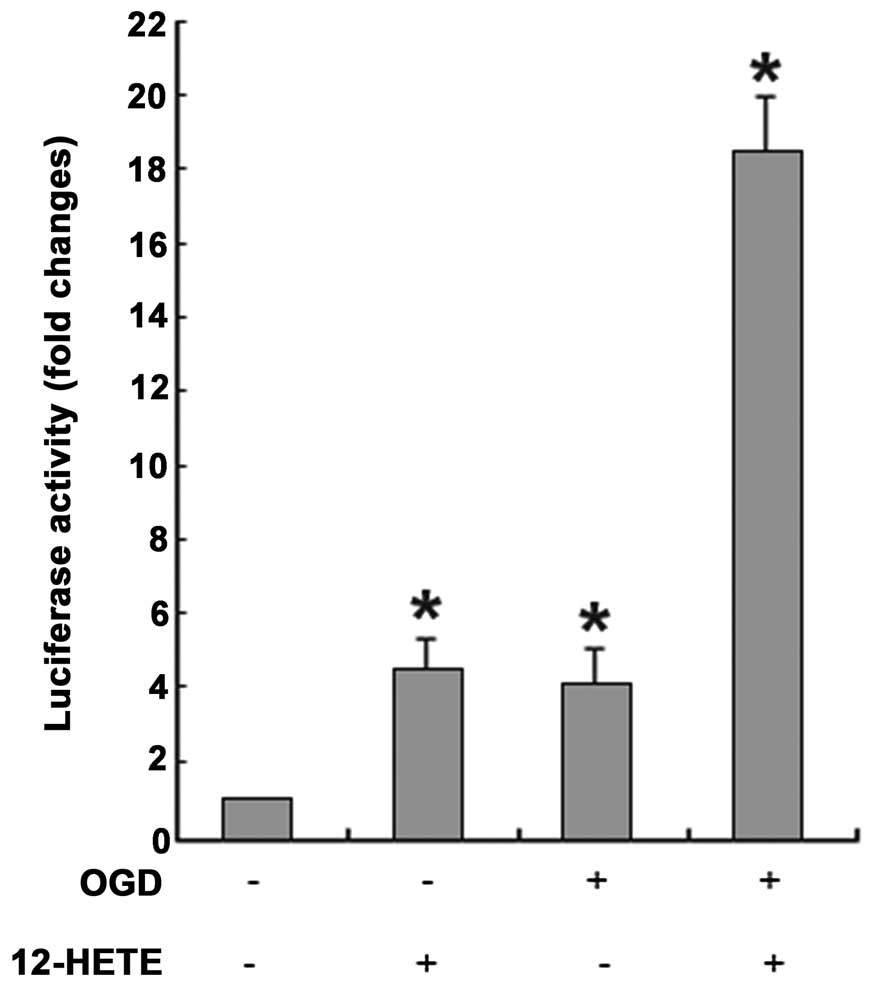

Normal cultured cortical neurons were transfected

with pGL3-PPRE and were subsequently treated with 12-HETE, OGD or

OGD plus 12-HETE. After 24 h, luciferase activities in the treated

neurons clearly increased compared to control neurons treated with

DMSO (t=−10.753, −9.679 and −21.978, respectively,

P<0.05). Luciferase activity increased similarly in 12-HETE- and

OGD-treated neurons with 4-fold changes, but luciferase activity

increased by 18-fold in neurons treated with OGD plus 12-HETE

(Fig. 9). Furthermore, relative

survival rates of neurons were measured with the MTT assay and the

possibility that luciferase activity was enhanced by cell survival

changes derived from 12-HETE or OGD treatment was excluded (data

not shown). Only minor luciferase activity was detected in

12-HETE-treated neurons transfected with pGL3-Basic, whereas

luciferase activity could not be detected in neurons transfected

with mixtures without any plasmids or in neuron lysates.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the

influence of 12/15-LOX on the activity of PPARγ in ischemia

reperfusion. This was of interest as this information may assist

with future treatment of brain ischemic injury. PPARγ is a member

of the nuclear receptor superfamily and a ligand-dependent

transcriptional factor. PPARγ activation leads to its nuclear

translocation in order to regulate the transcription of target

genes. Numerous studies have reported that PPARγ expression and

activity in brain tissues were induced by I/R injury (7–10),

and that PPARγ activation reduced infarct volume and inhibition of

inflammation mediators including intercellular adhesion molecule 1,

interleukin-β, cyclooxygenase-2 and iNOS (3,4,11,12). Therefore, it has been proposed

that induction of PPARγ expression and activation by brain ischemia

is a protective response to damage. This protective response may be

attributed to PPARγ activation induced by endogenous agonists

following ischemia, but the detailed mechanisms remain elusive.

12/15-LOX, a member of lipoxygenase family, is a

lipid peroxidase encoded by the ALOX15 gene that can oxidize

free polyunsaturated fatty acids and phospholipids in biological

membranes to generate oxidative products. 12-HETE is the oxidative

derivative of arachidonic acid catalyzed by 12/15-LOX. In brain

tissues, 12/15-LOX is mainly expressed in neurons or certain

astrocytes in the cerebral hemisphere, basal ganglia and

hippocampus. 12-HETE is the major product of 12/15-LOX in the

central nervous system (3).

Previous studies revealed that in brain tissues, 12/15-LOX may

exert its physiological functions through oxidative modifications

of membrane structures and generation of mediators or signaling

molecules with biological activities involved in synaptic

transmission (13,14). In vitro studies confirmed

that 12/15-LOX products, such as 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid

(13-HODE), 12-HETE and 15--HETE served as endogenous PPARγ

agonists. Furthermore, higher expression levels of 12/15-LOX

enhanced the transcriptional activation effect of PPARγ in specific

cell types. For example, in monocytes, 12/15-LOX products

interacted with PPARγ directly to stimulate the expression of

cluster of differentiation 36 and upregulate PPARγ expression

simultaneously (15). The

induction of PPARγ and its target genes by IL4 in macrophages

through the 12/15-LOX pathway has already been shown. Similarly,

13-HODE and 15-HETE PPARγ and increase the expression of

PPARγ mRNA in human vascular smooth muscle cells (16) and colon tumor cell line (17). Furthermore, in vivo

experiments have confirmed the regulatory effect of 12/15-LOX on

PPARγ and in the mouse uterus, PPARγ activation can occur through

the 12/15-LOX pathway to mediate the impact of 12/15-LOX on the

pregnant uterus (5). These

results indicate that elevation of PPARγ expression and activation

could be induced by 12/15-LOX in multiple tissues and cells.

Therefore, we speculate that 12/15-LOX has similar roles in the

central nervous system.

In the present study, I/R injury has been

demonstrated to induce the expression of 12/15-LOX and its product

12-HETE. A previous study implicated the upregulation of 12-HETE

level with oxidative stress caused by I/R injury in brain tissues

(18). However, other studies

have shown that 12-HETE is involved in synaptic transmission as a

second messenger in the central nervous system and that it also

participates in a variety of physiological activities, including

learning and memory (19,20). Notably, 12-HETE served as an

endogenous agonist of PPARγ to modulate its activity (5).

PPARγ is a nuclear transcription factor and

following activation it transports into the cell nucleus from the

cytoplasm to regulate the expression of target genes. Therefore,

the expression of PPARγ protein in the nucleus is associated with

its activity status. Regulation of target gene expression by PPARγ

is through PPARγ binding to a specific DNA element in the promoters

of the target genes (peroxisome proliferator responsive element,

termed PPRE) to promote target gene expression (21–23).

The present study revealed that 12-HETE intervention

in rats with I/R injury elevated the expression of PPARγ total

protein. Furthermore, treatment of OGD-damaged rat cortical neurons

with 12-HETE induced the expression of PPARγ, enhanced its binding

ability to DNA and promoted the expression of target genes,

suggesting the stimulatory effect of 12-HETE on PPARγ activity.

Several associated studies have reported an inhibitory effect of

PPARγ on inflammation following ischemia. For instance, PPARγ

agonists, including pioglitazone, rosiglitazone and troglitazone,

reduced infarct volume, improved neuron functions, suppressed the

expression of variant inflammatory mediators, reduced neutrophil

infiltration, and inhibited the activation of microglias,

macrophages and the inflammation-associated NF-κB pathway (4,10–12). Furthermore, other studies have

reported that the neuroprotective effect of PPARγ is partially

achieved through suppression of iNOS expression and activation

(24–27). In accordance with these results,

it was observed that elevated expression of iNOS in brain tissues

with I/R injury was inhibited by 12-HETE intervention and PPARγ

activity was stimulated simultaneously, indicating that

12-HETE-induced PPARγ activation inhibited inflammation responses,

to achieve a neuroprotective effect.

Antisense oligonucleotides were also used to inhibit

the expression of 12/15-LOX and revealed that PPARγ nuclear

expression was negatively regulated by asON-12/15-LOX, confirming

the regulatory effect of 12/15-LOX on PPARγ. Cell transfection

reagents are often used to promote the delivery of antisense

oligonucleotides into cells to enhance the inhibitory effect.

However, cell transfection reagents often damage cells. As primary

cultured neurons in vitro are vulnerable and prone to

injury, the oligonucleotides were dissolved into the culture medium

directly to treat neurons. This method inhibited the expression of

12/15-LOX significantly, indicating its feasibility. Previous

studies have also proved the efficiency of such methods in sensory

neuron treatment (6,28).

The present study has certain limitations. Rat-based

models of oxygen-glucose deprivation and ischemia reperfusion were

used, however, it would be noteworthy to observe if the role of

12/15-LOX can also be followed in human derived cells. A number of

details of the mechanism of PPARγ protection remain to be revealed

and therefore, further work is required prior to considering these

results in terms of clinical therapy.

In conclusion, the level of the 12/15-LOX-derived

product 12-HETE was significantly elevated in OGD-treated cortical

neurons and confirmed the agonistic effect of 12-HETE on PPARγ. The

expression of PPARγ nuclear expression could be blocked with

12/15-LOX inhibition in OGD-treated neurons. These results revealed

that PPARγ is activated by the 12/15-LOX pathway in OGD-treated

neurons and that PPARγ activation has a neuroprotective effect,

indicating that it is a neuronal self-protective response to damage

and injury.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81401023).

References

|

1

|

Boyle PJ: Diabetes mellitus and

macrovascular disease: mechanisms and mediators. Am J Med. 120(9

Suppl): S12–S17. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Xu YW, Sun L, Liang H, Sun GM and Cheng Y:

12/15-lipoxygenase inhibitor baicalein suppresses PPAR gamma

expression and nuclear translocation induced by cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion. Brain Res. 1307:149–157. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Collino M, Aragno M, Mastrocola R, et al:

Modulation of the oxidative stress and inflammatory response by

PPAR-gamma agonists in the hippocampus of rats exposed to cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion. Eur J Pharmacol. 530:70–80. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhao Y, Patzer A, Herdegen T, Gohlke P and

Culman J: Activation of cerebral peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptors gamma promotes neuroprotection by attenuation of neuronal

cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression after focal cerebral ischemia in

rats. FASEB J. 20:1162–1175. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li Q, Cheon YP, Kannan A, Shanker S,

Bagchi IC and Bagchi MK: A novel pathway involving progesterone

receptor, 12/15-lipoxygenase-derived eicosanoids and peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor gamma regulates implantation in

mice. J Biol Chem. 279:11570–11581. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lebeau A, Terro F, Rostene W and Pelaprat

D: Blockade of 12-lipoxygenase expression protects cortical neurons

from apoptosis induced by beta-amyloid peptide. Cell Death Differ.

11:875–884. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ou Z, Zhao X, Labiche LA, et al: Neuronal

expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma

(PPARgamma) and 15d-prostaglandin J2-mediated protection of brain

after experimental cerebral ischemia in rat. Brain Res.

1096:196–203. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sundararajan S, Gamboa JL, Victor NA,

Wanderi EW, Lust WD and Landreth GE: Peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligands reduce inflammation

and infarction size in transient focal ischemia. Neuroscience.

130:685–696. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Pereira MP, Hurtado O, Cárdenas A, et al:

Rosiglitazone and 15-deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 cause potent

neuroprotection after experimental stroke through noncompletely

overlapping mechanisms. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 26:218–229. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chu K, Lee ST, Koo JS, et al: Peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-agonist, rosiglitazone,

promotes angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res.

1093:208–218. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tureyen K, Kapadia R, Bowen KK, et al:

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists induce

neuroprotection following transient focal ischemia in normotensive,

normoglycemic as well as hypertensive and type-2 diabetic rodents.

J Neurochem. 101:41–56. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhao X, Strong R, Zhang J, et al: Neuronal

PPARgamma deficiency increases susceptibility to brain damage after

cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 29:6186–6195. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Czapski GA, Czubowicz K and Strosznajder

RP: Evaluation of the antioxidative properties of lipoxygenase

inhibitors. Pharmacol Rep. 64:1179–1188. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Giannopoulos PF, Joshi YB, Chu J and

Praticò D: The 12–15-lipoxygenase is a modulator of

Alzheimer’s-related tau pathology in vivo. Aging Cell.

12:1082–1090. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Praticò D, Zhukareva V, Yao Y, et al:

12/15-lipoxygenase is increased in Alzheimer’s disease: possible

involvement in brain oxidative stress. Am J Pathol. 164:1655–1662.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Limor R, Sharon O, Knoll E, Many A,

Weisinger G and Stern N: Lipoxygenase-derived metabolites are

regulators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-2

expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Hypertens.

21:219–223. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bull AW, Steffensen KR, Leers J and Rafter

JJ: Activation of PPAR gamma in colon tumor cell lines by oxidized

metabolites of linoleic acid, endogenous ligands for PPAR gamma.

Carcinogenesis. 24:1717–1722. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yao Y, Clark CM, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM

and Pratico D: Elevation of 12/15 lipoxygenase products in AD and

mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 58:623–626. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Palluy O, Bendani M, Vallat JM and Rigaud

M: 12-lipoxygenase mRNA expression by cultured neurons. C R Acad

Sci III. 317:813–818. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Pekcec A, Yigitkanli K, Jung JE, Pallast

S, Xing C, Antipenko A, Minchenko M, Nikolov DB, Holman TR, Lo EH

and van Leyen K: Following experimental stroke, the recovering

brain is vulnerable to lipoxygenase-dependent semaphorin signaling.

FASEB J. 27:437–445. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

21

|

Marcus SL, Miyata KS, Zhang B, Subramani

S, Rachubinski RA and Capone JP: Diverse peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptors bind to the peroxisome

proliferator-responsive elements of the rat hydratase/dehydrogenase

and fatty acyl-CoA oxidase genes but differentially induce

expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 90:5723–5727. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Okuno Y, Matsuda M, Miyata Y, et al: Human

catalase gene is regulated by peroxisome proliferator activated

receptor-gamma through a response element distinct from that of

mouse. Endocr J. 57:303–309. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Venkatachalam G, Kumar AP, Yue LS, Pervaiz

S, Clement MV and Sakharkar MK: Computational identification and

experimental validation of PPRE motifs in NHE1 and MnSOD genes of

human. BMC Genomics. 10(Suppl 3): S52009. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

24

|

Gresa-Arribas N, Viéitez C, Dentesano G,

Serratosa J, Saura J and Solà C: Modelling neuroinflammation in

vitro: a tool to test the potential neuroprotective effect of

anti-inflammatory agents. PLoS One. 7:e452272012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kapinya KJ, Löwl D, Fütterer C, et al:

Tolerance against ischemic neuronal injury can be induced by

volatile anesthetics and is inducible no synthase dependent.

Stroke. 33:1889–1898. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Choi SH, Lee DY, Kim SU and Jin BK:

Thrombin-induced oxidative stress contributes to the death of

hippocampal neurons in vivo: role of microglial NADPH oxidase. J

Neurosci. 25:4082–4090. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Xing B, Xin T, Hunter RL and Bing G:

Pioglitazone inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide

synthase is associated with altered activity of p38 MAP kinase and

PI3K/Akt. J Neuroinflammation. 5:42008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mulderry PK and Dobson SP: Regulation of

VIP and other neuropeptides by c-Jun in sensory neurons:

implications for the neuropeptide response to axotomy. Eur J

Neurosci. 8:2479–2491. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|