Introduction

Gastric cancer is a prevalent malignant tumor and

>1,000,000 new cases were diagnosed in 2020. Notably, gastric

cancer ranks as the fifth most common cancer in terms of incidence

and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide

(1). Despite advancements in

treatment modalities, the overall prognosis remains poor,

highlighting the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies

(1,2). This type of cancer originates from

the gastric mucosa, and exhibits diverse epidemiological patterns,

risk factor profiles and molecular subtypes influenced by

geographical variability (3–5).

Current therapeutic options, including surgical resection,

chemotherapy, targeted agents and immunotherapy, have demonstrated

limited success in improving the outcome of patients, especially in

cases of metastatic gastric cancer (6–9). The

emergence of chemoresistance, particularly to platinum-based

compounds such as cisplatin (DDP), severely restricts the

effectiveness of standard treatments (10). Consequently, there is a need for

in-depth research into the underlying mechanisms of resistance and

the development of innovative therapeutic strategies. Such

advancements are key for enhancing treatment response, and

tailoring more efficacious and individualized interventions for

patients with gastric cancer.

In the contemporary landscape of oncology, where

targeted therapy and immunotherapy have become the basis of cancer

treatment, research into immune cells within the tumor

microenvironment (TME) is increasingly pivotal (11–13).

Macrophages, as key immune effector cells, have a dual role in the

TME, both influencing and being influenced by tumor dynamics

(14). Macrophages are broadly

classified into two phenotypes: Classically activated macrophages

(M1), which enhance cytokine production and exert antitumor

effects, and alternatively activated macrophages (M2), which are

associated with tumor promotion and immunosuppression (15). In most solid tumors, including

gastric cancer, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are

predominantly skewed towards the M2 phenotype (16). The density and polarization state

of TAMs are intricately associated with essential oncogenic

processes, such as metastasis, invasion and chemoresistance

(16,17).

Exosomes, a subset of extracellular vesicles, have a

key role in intercellular communication by transporting bioactive

molecules, including microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs), lipids and proteins

(18). Previous studies have

suggested that stromal cells in the TME, particularly TAMs, can

modulate tumor cell behavior and facilitate oncogenesis through

exosome secretion (19,20). miRNAs, as a significant component

of exosomes, are encapsulated within a bilipid layer that protects

them from enzymatic degradation, ensuring their stability during

transport to recipient cells (20). Upon delivery, these miRNAs can

regulate gene expression by binding to target mRNAs, resulting in

mRNA degradation or translational repression (19,21,22).

The present study aimed to investigate the role and

underlying mechanisms of exosomes derived from M2-polarized

macrophages in modulating DDP resistance in gastric cancer cells,

using a well-established model of M2-polarized macrophages to mimic

TAM functions in the TME (23,24).

Targeting exosomal miR-3681-3p derived from M2-polarized

macrophages may present a promising therapeutic strategy to

overcome DDP resistance in gastric cancer, offering a potential

pathway for increasing treatment efficacy.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

AGS gastric cancer cells (cat. no. CRL-1739;

American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in DMEM (cat. no.

11965092, Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with

10% FBS (cat. no. 16140071; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5%

CO2. Primary mouse bone marrow cells (MBMCs; cat. no.

CP-M131; Wuhan Pricella Life Technology Co. Ltd.), were maintained

in DMEM/F-12 (cat. no. 11330032; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) enriched with 10% FBS and macrophage colony-stimulating

factor (cat. no. HY-P7085A; MedChemExpress) at 37°C and 5%

CO2. For M2 polarization, MBMCs were treated with

interleukin (IL)-4 (30 ng/ml; cat. no. 214-14-1MG) and IL-13 (30

ng/ml; cat. no. 210-13-1MG) (both from Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 48 h at 37°C. Co-culture assays were

conducted using a Transwell system, wherein 5×104

M2-polarized macrophages were seeded into 12-well plate inserts

(upper chamber), and 1.5×105 AGS cells were grown in the

lower compartment at 37°C for 3 days.

Immunofluorescence

A total of 2×104 M2-polarized macrophages

were cultured in 35-mm confocal dishes for 48 h, followed by

fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature.

After fixation, the cells were washed three times for 5 min with

PBS and were then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for

10 min at room temperature (RT). Blocking was achieved by

incubating the cells with 3% BSA (cat. no. 23225; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) in PBS for 1 h at RT. Subsequently, the cells

were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies targeting

CD206 (1:200 dilution; cat. no ab64693; Abcam), CD163 (1:50

dilution; cat. no ab316218; Abcam), CD80 (1:200 dilution; cat. no

ab315832; Abcam) and CD86 (1:100 dilution; cat. no ab239075;

Abcam). This was followed by incubation with fluorophore-conjugated

secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution; cat. no A27039; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 2 h at room temperature. After three

additional washes with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1%

Tween-20, the nuclei were stained with DAPI (cat. no. D1306; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 10 min at 37°C to facilitate nuclear

visualization. Imaging was carried out using a Carl Zeiss LSM 510

META confocal microscope (Zeiss GmbH) equipped with a Plan

Apochromat 63× oil immersion objective featuring a numerical

aperture of 1.4 and differential interference contrast

capability.

Detection of inflammatory factors

Pro-inflammatory cytokine concentrations in the

culture supernatants of M2-polarized macrophages were

quantitatively evaluated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA). A total of 1×104 M2 macrophages were plated in

24-well plates and cultured for 48 h. Subsequently, the

supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Levels of IL-2 (cat. no. JM-02981M1), IL-10 (cat. no. JM-02459M2),

IL-6 (cat. no. JM-02446M1) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α; cat.

no. JM-02415M2) were determined using specific ELISA kits (Jiangsu

Jingmei Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). All procedures were carried out

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell proliferation and viability

assay

AGS cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a

concentration of 1×103 cells/well overnight, followed by

incubation with 1 µg/ml DDP for 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 days at 37°C. At

the end of each timepoint, 10 µl Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

solution (cat. no. C0039; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was

added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h

to allow the reaction to occur. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured

using an Eppendorf BioPhotometer® D30 (Eppendorf SE).

Cell proliferation was quantitatively determined based on the

absorbance readings collected over a 5-day period.

In addition, AGS cells were cultured in 96-well

plates at a concentration of 1×103 cells/well overnight,

and were then incubated with 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 µM DDP for 48 h

at 37°C. Then, 10 µl CCK-8 solution was added to each well, and the

plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h to allow the reaction to

occur. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using an Eppendorf

BioPhotometer D30. IC50 values were calculated using

non-linear regression in GraphPad Prism (version 8.0;

Dotmatics).

Flow cytometry

The apoptosis of AGS cells was quantified using the

Annexin V-FITC and PI staining kit (cat. no. G1511; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Analysis was carried out using a Beckman DXI800 flow

cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). The identification and

quantification of apoptotic cells, indicated by PI positivity, were

conducted with FlowJo software (version 10.8; BD Biosciences). The

apoptotic rate was calculated by summing the percentages of cells

in both early and late stages of apoptosis.

Isolation of exosomes and electron

microscopy

M2-polarized macrophage supernatants were collected

and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Following

centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-µm

syringe filter (cat. no. SLGVR13SL; MilliporeSigma) and subjected

to ultracentrifugation at 120,000 × g overnight at 4°C using an

Optima XPN-100 ultracentrifuge (cat. no. CP100MX; Hitachi, Ltd.) to

precipitate exosomes. The exosomes were then resuspended in cold

PBS (pH 7.4) and further purified by ultracentrifugation at 120,000

× g for 90 min at 4°C. The purified exosomes were suspended in cold

PBS or SDS loading buffer (cat. no. P0015F; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology; containing 4% SDS and 100 mM Tris-HCl; pH 7.6) and

stored at −80°C for further studies. For the in vitro

experiments, exosomes were used to treat cells at a concentration

of 50 µg protein/105 cells at 37°C for 48 h.

For transmission electron microscopy, freshly

isolated exosome suspensions were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for

1 h at 4°C. Subsequently, 20 µl exosome solution was placed onto a

copper grid, excess fluid was removed, and the sample was stained

with 2% phosphotungstic acid for 40 sec at room temperature to

enhance contrast. Visualization of the exosomes was caried out

using a transmission electron microscope (model HT-7700; Hitachi,

Ltd.). In addition, the exosome supernatant was denatured with 5X

SDS buffer and analyzed by western blotting. Protein samples (50

µg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel

and were probed with rabbit antibodies targeting calnexin (1:1,000

cat. no. ab133615; Abcam), tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101;

1:1,000; cat. no. 102286-T38; Beijing Sino Technology Co. Ltd.) and

CD9 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab92726; Abcam). The detailed western

blotting procedures are described in the western blotting

subsection.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis

(NTA)

M2-polarized macrophage-extracted exosomes were

diluted to a total volume of 1 ml using Tris-phosphate-modified

saline for subsequent analysis. To assess the size distribution of

the exosomes, NTA was carried out using a NanoSight (model, N30E;

NanoFCM, Inc.) instrument. This analysis adhered to the established

standard operating procedure for NTA (25), enabling precise measurement of

vesicle size based on the Brownian motion of individual

particles.

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted from AGS cells using

radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (cat. no. HY-K1001;

MedChemExpress), and their concentration was measured using the BCA

Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. 23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

For SDS-PAGE, 10 µg each protein lysate was combined with 5X SDS

sample buffer and separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

Post-electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. To minimize non-specific

interactions, the membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 2 h

at RT. The membrane was then probed overnight at 4°C with the

following primary antibodies: Rabbit anti-MLH1 (1:2,000; cat. no.

ab92312; Abcam) and mouse anti-GAPDH (1:5,000; cat. no. ab8245;

Abcam). After incubation with primary antibodies, the membrane was

rinsed and exposed to HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies

(1:10,000; cat. nos. ab6721 and ab205719; Abcam) for 2 h at RT.

Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence

western blot detection reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

ImageJ software (version 1.53a; National Institutes of Health) was

used for semi-quantification of western blot analysis.

miR-3681-3p mimic and MLH1 small

interfering (si)RNA transfections

The miR-3681-3p mimic (sense:

5′-ACACAGUGCUUCAUCCACUACU-3′; antisense:

5′-AGUAGUGGAUGAAGCACUGUGU-3′) and its negative control (NC: sense:

5′-UUUGUACUACACAAAAGUACUG-3′; antisense:

5′-CAGUACUUUUGUGUAGUACAAA-3′) were synthesized by Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd. Transfection of AGS cells with the miR-3681-3p

mimic was carried out using Oligofectamine™ reagent

(cat. no. 12252-011; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. This involved 24-h

serum-free pre-treatment of AGS cells, followed by transfection

with a final concentration of 50 nM miR-3681-3p mimic or NC for 48

h. Transfection efficiency was subsequently assessed using reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR).

The MLH1 siRNA (sense: 5′-CAGCUAAUGCUAUCAAAGAGA-3′;

antisense: 5′-UCUCUUUGAUAGCAUUAGCUG-3′) and its scrambled NC siRNA

(sense: 5′-UUCUCCGAACGAGUCACGUTT-3′; antisense:

5′-ACGUGACUCGUUCGGAGAA-3′) were also synthesized by Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd. The transfection procedure for MLH1 siRNA

followed the protocol used for the miR-3681-3p mimic.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from exosomes derived from

M2 macrophages or AGS cells using the RNAiso Plus reagent (cat. no.

9109; Takara Bio, Inc.). The isolated RNA was then

reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the Bestar™ qPCR RT

kit (cat. no. DBI-2220; DBI Bioscience). RT followed a defined

thermal profile: 5 min at 25°C, 30 min at 42°C and a final step at

85°C for 5 min. qPCR was conducted to assess the expression levels

of target genes using Bestar qPCR MasterMix (cat. no. DBI-2043; DBI

Bioscience) on the Agilent Mx3000P system (cat. no. Mxpro-Mx3000P;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The qPCR amplification used a two-step

protocol: 30 sec at 95°C for initial denaturation, followed by 40

cycles of 10 sec at 95°C and 30 sec at 60°C. Relative expression

levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (26), with normalization of miR-3681-3p

expression to U6 snRNA levels. The specific primer sequences used

for amplification were as follows: miR-3681-3p forward,

5′-CGCGACACAGTGCTTCATCC-3′, reverse, 5′-AGTAGTGGATGAAGCACTGT-3′;

and U6 snRNA forward, 5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3′ and reverse,

5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′.

Target identification and

dual-luciferase reporter assay

RNAhybrid v2.2 online software (https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid)

was used for miR-3681-3p target prediction (27). Wild-type and mutant MLH1 gene

3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) were cloned into the pmirGLO

dual-luciferase reporter vector (cat. no. E1910; Promega

Corporation). Briefly, 3×105 293T cells (cat. no.

CL-0005; Wuhan Pricella Life Technology Co. Ltd.) underwent

co-transfection with these vectors alongside either the miR-3681-3p

mimic or NC mimic using the HB-TRLF-1000 LipoFiter transfection kit

(cat. no. HB-TRLF-1000; Hanbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Following

a 48-h incubation period at 37°C, cell lysates were collected, and

luciferase activity was measured according to the instructions of

the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (cat. no. E1910; Promega

Corporation). Luminescence was quantified using a Lux-T020

microplate reader. The activation of the reporter gene was

evaluated by calculating the normalized luminescence data,

expressed as the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase

activities.

Vector construction and lentiviral

transduction

A lentiviral vector engineered for MLH1

overexpression was created using human MLH1 genetic sequences

obtained from the NCBI GenBank (Gene Bank ID: FJ940753.1,

accessible at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/FJ940753.1) by

Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. The coding sequence of MLH1 was

inserted into the GV358 vector to yield the MLH1 overexpression

vector. An empty GV358 vector was used in the NC group.

AGS cells were cultured in 6-well plates at 37°C for

36 h. Once they had reached ~70% confluence, each well was

uniformly exposed to equivalent volumes (100 µl) of

MLH1-overexpressing lentiviral particles or NC (empty vector)

lentiviral particles at a multiplicity of infection of 10 for 48 h

at 37°C. After 48 h, the AGS cells were harvested for western

blotting and the CCK-8 assay.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data from the experiments were analyzed

using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0; Dotmatics). All

experimental protocols were carried out in triplicate to ensure

reproducibility and accuracy. Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using the

unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test for comparisons between two

distinct groups. For multiple group comparisons, one-way ANOVA was

applied, followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test for post hoc

analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Co-culturing gastric cancer cells with

M2-polarized macrophages increases resistance to DDP

To investigate how M2-polarized macrophages affect

the resistance of gastric cancer cells to DDP, MBMCs were treated

with IL-13 and IL-4 to promote M2 polarization. These M2

macrophages were characterized by the presence of specific M2

markers, such as CD206 and CD163, and the lack of M1 markers, such

as CD80 and CD86, verified through immunophenotyping (Fig. 1A). Additionally, an increase in

M2-associated cytokines, including IL-2, IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α was

observed in these cells compared with in resting macrophages

(Fig. 1B). In subsequent

experiments, DDP treatment significantly reduced the proliferation

and increased the apoptosis of AGS gastric cancer cells when

compared with the untreated control. However, co-culture with

M2-polarized macrophages attenuated the cytotoxic effects of DDP,

suggesting that M2 macrophages may confer resistance to DDP in AGS

cells (Fig. 1C and D).

M2-polarized macrophage-derived

exosomes contribute to DDP resistance in gastric cancer cells

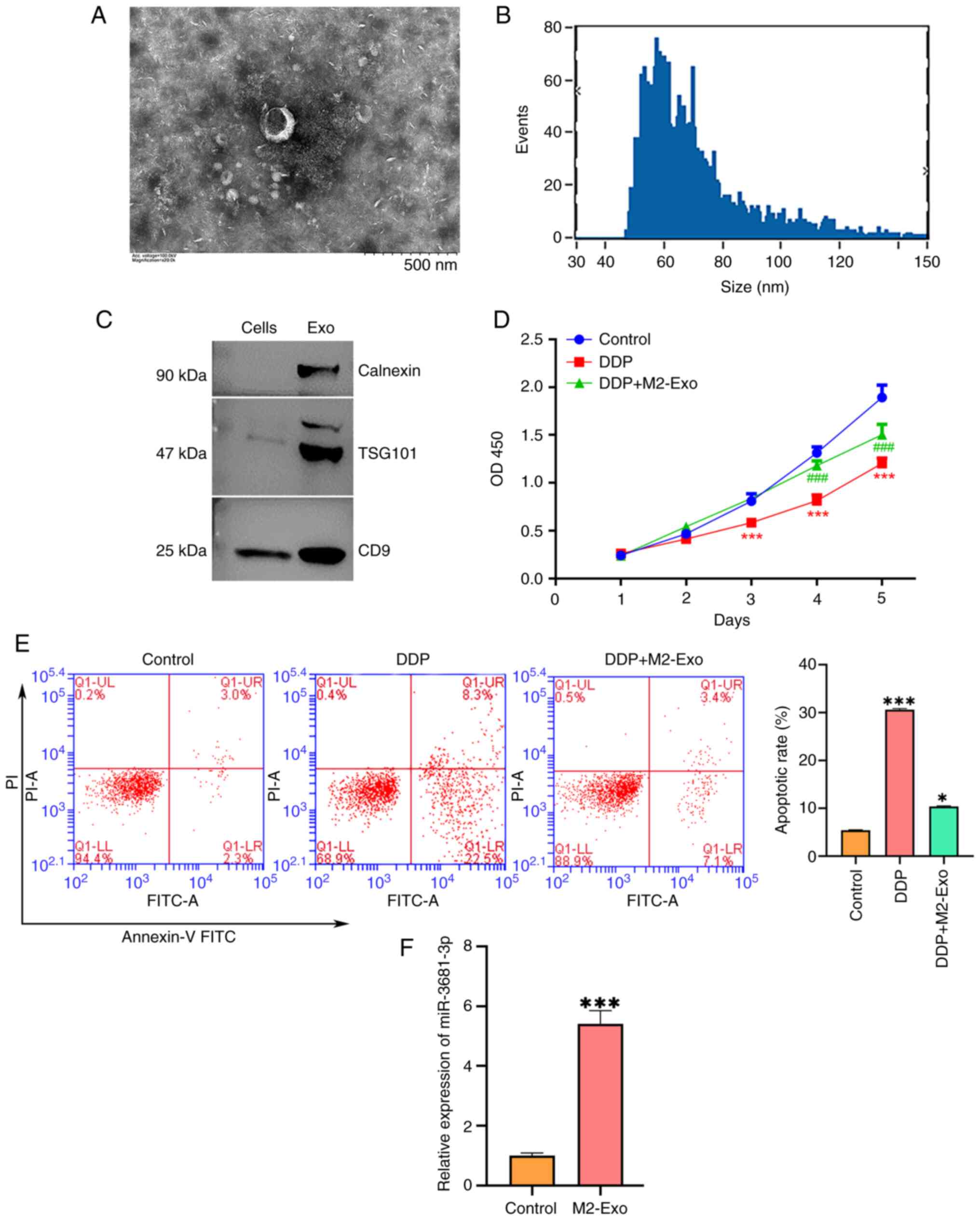

Electron microscopy analysis of the M2-polarized

macrophage-derived supernatant revealed the presence of small

vesicles consistent with exosomes, characterized by a 50–100 nm

diameter (Fig. 2A and B). The

exosome fraction was enriched with established markers, including

the endoplasmic reticulum protein calnexin, TSG101 and CD9, as

confirmed by western blotting (Fig.

2C). Notably, exosomes derived from M2 macrophages

significantly promoted the proliferation and inhibited the

apoptosis of DDP-treated AGS cells (Fig. 2D and E). Additionally, the

expression levels of miR-3681-3p were markedly higher in exosomes

from M2 macrophages than those from resting macrophages (Fig. 2F). These findings suggested that

M2-polarized macrophages may mitigate the cytotoxic effects of DDP

on AGS cells through the release of exosomes enriched with

miR-3681-3p.

miR-3681-3p increases the DDP

resistance of gastric cancer cells by downregulating MLH1

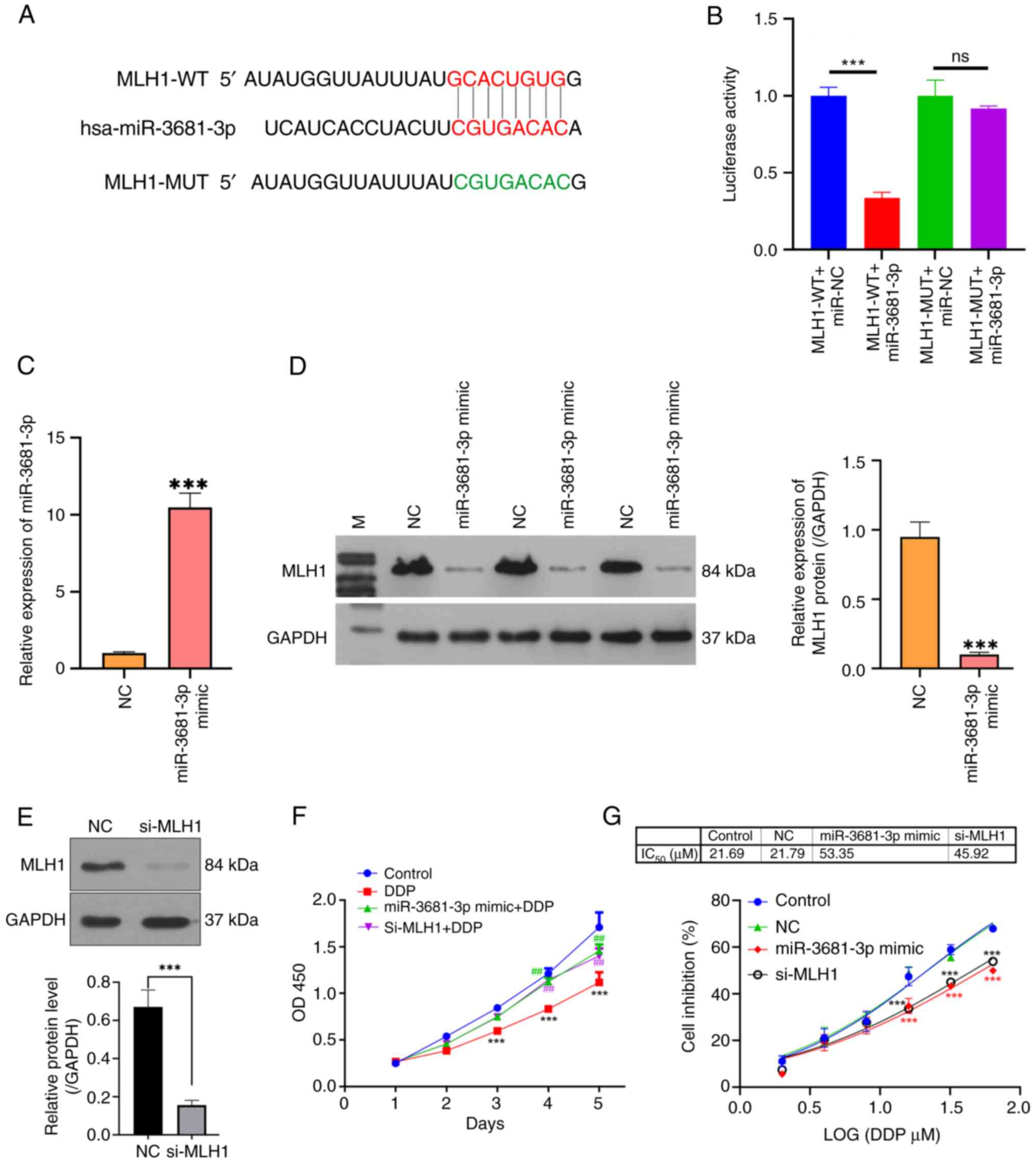

Potential target genes of miR-3681-3p were

identified using the RNAhybrid v2.2 online software. Analysis

indicated that miR-3681-3p may target the gene encoding MLH1

(Fig. 3A). To validate this

interaction, luciferase reporter vectors were constructed

containing either wild-type or mutant forms of the MLH1 3′-UTR.

Transfection with the miR-3681-3p mimic resulted in a significant

reduction in luciferase activity associated with the wild-type MLH1

3′-UTR compared with the miR-NC. This suppressive effect was absent

in the mutated MLH1 3′-UTR construct, confirming the specificity of

the interaction (Fig. 3B). To

further validate whether miR-3681-3p targets and regulates the

expression of MLH1, the expression of miR-3681-3p was increased in

AGS cells by transfection with a miR-3681-3p mimic (Fig. 3C). Moreover, miR-3681-3p mimic

transfection substantially decreased the expression levels of MLH1

protein (Fig. 3D). Additionally,

knockdown of MLH1 protein expression was achieved by siRNA

transfection (Fig. 3E). Functional

assays demonstrated that both miR-3681-3p mimic transfection and

MLH1 silencing by siRNA rescued the DDP-induced suppression of AGS

cell proliferation (Fig. 3F).

Moreover, both miR-3681-3p mimic transfection and MLH1 silencing

contributed to the drug resistance of AGS cells to DDP, as

evidenced by an increase in the IC50 value from 21.69 to

53.35 and 45.92 µM, respectively (Fig.

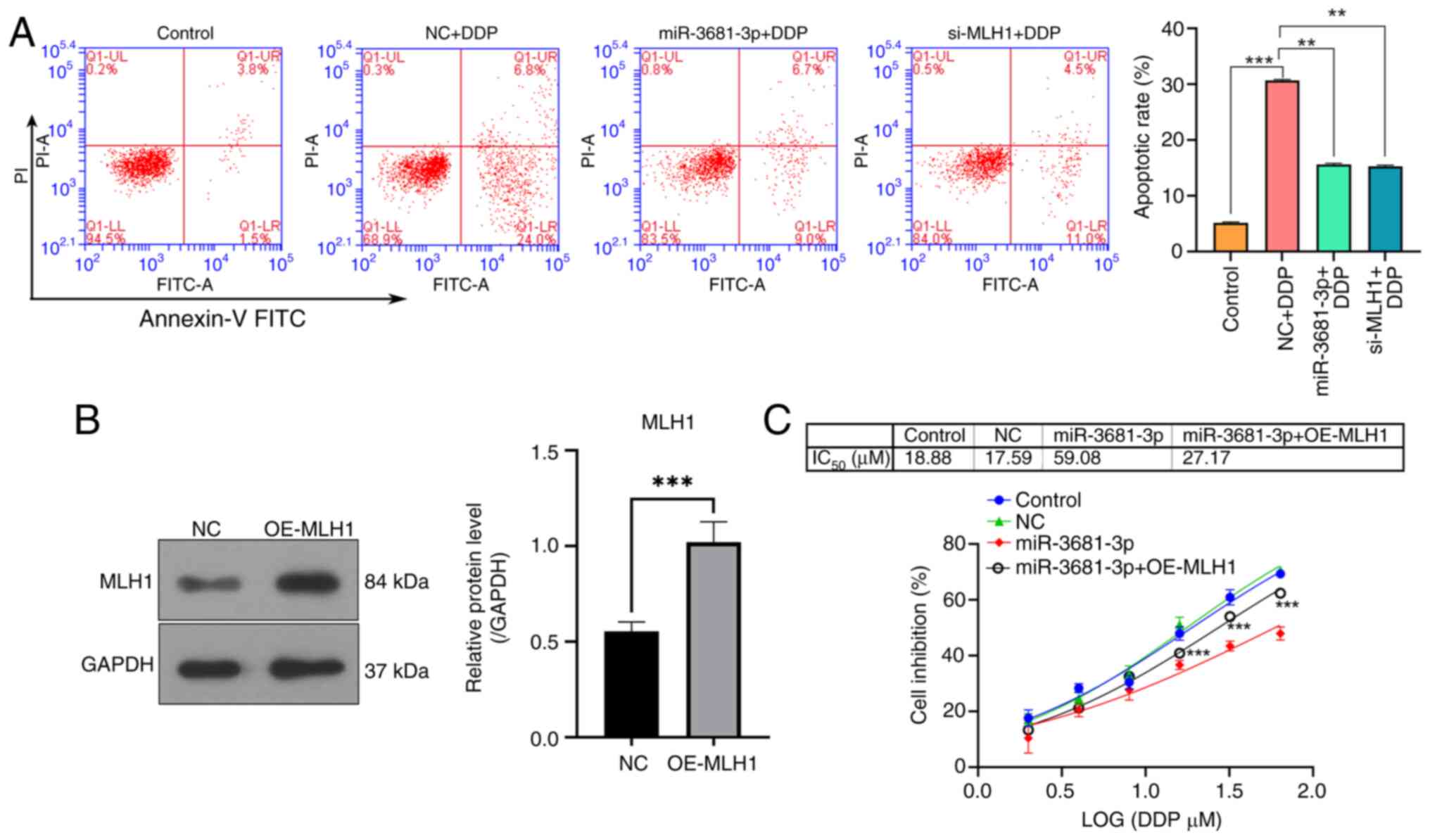

3G). Additionally, both miR-3681-3p overexpression and MLH1

knockdown significantly reduced the apoptotic rate of AGS cells

exposed to DDP treatment (Fig.

4A). By contrast, the overexpression of MLH1 significantly

reversed the drug resistance of AGS cells to DDP caused by

miR-3681-3p mimic treatment, as evidenced by a decrease in the

IC50 value from 59.08 to 27.17 µM (Fig. 4B and C).

| Figure 3.miR-3681-3p increases DDP resistance

in gastric cancer cells by downregulating MLH1. (A) Bioinformatics

analysis was utilized to predict the binding site of miR-3681-3p to

MLH1. (B) Results of the dual-luciferase reporter assay assessing

the interaction between miR-3681-3p and MLH1. ***P<0.001. (C)

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR was used to measure the

expression levels of miR-3681-3p in AGS cells after miR-3681-3p

mimic transfection. (D) Western blot analysis was carried out to

determine the protein levels of MLH1 in AGS cells transfected with

the miR-3681-3p mimic. (E) Protein levels of MLH1 were detected by

western blotting after si-MLH1 transfection. Grayscale analysis was

conducted using ImageJ software. ***P<0.001 vs. NC group. (F)

Cell proliferation of miR-3681-3p mimic-transfected and

si-MLH1-transfected AGS cells was assessed by CCK-8 assay. (G) The

IC50 value was calculated using GraphPad software based

on CCK-8 assay results. Quantitative data are presented as the mean

± SD (n=3). ***P<0.001 vs. control group; ##P<0.01

vs. DDP group. CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; DDP, cisplatin; miR,

microRNA; MLH1, MutL protein homolog 1; MUT, mutant; NC, negative

control; ns, not significant; OD, optical density; si, small

interfering; WT, wild-type. |

Discussion

Gastric cancer, characterized by unchecked

proliferation of neoplastic cells in the gastric mucosa, is a

leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (2,9). Its

high mortality rate is largely attributed to late-stage diagnosis

and high metastatic potential (7,9).

DDP, the first platinum analog approved for clinical use in 1971,

is extensively used as a first-line treatment for gastric cancer,

either alone or in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents

(28–30). However, DDP-based therapies face

notable limitations in certain patients, primarily due to adverse

effects, such as nephrotoxicity, insufficient therapeutic efficacy

and the development of tumor resistance (31,32).

In gastric cancer, considerable knowledge gaps exist

regarding DDP resistance, particularly in understanding the

specific mechanisms underlying this resistance in gastric cancer

cells. Factors such as genetic mutations, epigenetic alterations

and the role of extracellular vesicles remain inadequately

investigated (33–35). Additionally, there is a notable

absence of reliable biomarkers to predict which patients may

develop resistance to DDP, impacting the implementation of

personalized therapy (36). While

some new drugs and treatments are under investigation, effective

options for managing drug-resistant gastric cancer are limited

(37). Researchers are actively

working to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of DDP resistance

using advanced technologies, including genomics, transcriptomics

and proteomics (38,39). Clinical trials are being conducted

to assess new treatment combinations and alternative therapies

aimed at overcoming DDP resistance (40,41).

The identification of biomarkers of resistance through genomic

analysis is key for developing personalized treatment plans and

advancing precision medicine (42,43).

In the near future, a wealth of new research findings is

anticipated that will enhance the understanding of DDP resistance

mechanisms, thereby laying the groundwork for innovative

therapeutic strategies (44,45).

Ongoing research holds promise for identifying effective biomarkers

that can aid in selecting suitable patients for DDP therapy

(46). Additionally, novel drugs

and treatment combinations are likely to emerge in clinical

practice, potentially improving outcomes for patients with

DDP-resistant gastric cancer (47). Researchers are expected to

strengthen interdisciplinary collaboration, merging basic and

clinical research efforts to expedite the development and

application of new therapies (48,49).

Through these collective efforts, the aim is to effectively tackle

the challenges posed by DDP resistance, and enhance treatment

efficacy and survival rates for patients with gastric cancer.

Investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying

DDP resistance is key for enhancing therapeutic efficacy. In the

present study, the role of exosomal miR-3681-3p, derived from

M2-polarized macrophages, in fostering DDP resistance in gastric

cancer cells was elucidated. This was achieved through the

downregulation of MLH1 expression levels, providing novel

mechanistic insights into the modulation of chemoresistance. The

role of the miR-3681-3p/MLH1 axis indicates a promising therapeutic

approach to overcome DDP resistance in gastric cancer.

M2 macrophages, which are involved in tissue repair

and immunoregulation, significantly influence tumor progression by

creating a supportive environment for cancer growth, angiogenesis

and metastasis (50–52). These macrophages undergo metabolic

reprogramming in the TME, supporting their survival and enhancing

their immunosuppressive functions (24,53).

M2 macrophages have been shown to mediate tumor resistance to

various chemotherapeutic agents. For instance, M2 macrophages

activate signaling pathways such as CXCR2, promoting resistance to

sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma (54). In glioblastoma, hypoxia-driven M2

polarization facilitates cancer aggressiveness and resistance to

temozolomide (55). Additionally,

M2 macrophages modulate cholesterol homeostasis, suppress

ferroptosis and support their own polarization, exacerbating

hepatocellular carcinoma progression and contributing to drug

resistance (56). In gastric

adenocarcinoma, M2 macrophages have been reported to mediate

resistance to 5-fluorouracil through the regulation of integrin β3,

focal adhesion kinase and cofilin expression (57). In the present study, M2

polarization of MBMCs was induced through the administration of

IL-13 and IL-4. This induction resulted in the expression of

M2-specific markers (CD206 and CD163) and the upregulation of

associated cytokines (IL-2, IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α). Notably, the

results of the present study indicated that co-culturing gastric

cancer cells with M2-polarized macrophages increased resistance to

DDP, suggesting an association between M2 polarization and DDP

resistance.

M2 macrophages affect tumor cells either directly or

by secreting exosomes containing specific miRNAs that modulate

tumor behavior and immune responses (58–60).

For example, exosomal miR-23a-3p from M2 macrophages has been shown

to promote oral squamous cell carcinoma progression by inhibiting

PTEN (58). Similarly, exosomes

carrying miR-660-5p from M2 macrophages facilitate hepatocellular

carcinoma development by downregulating KLF3 (59). Notably, exosomal miR-588 from

M2-polarized macrophages has been implicated in DDP resistance in

gastric cancer cells (60). These

findings highlight the complex roles of M2 macrophages and their

miRNA contents in driving tumor drug resistance, emphasizing the

potential for therapeutic strategies targeting these mechanisms to

enhance cancer treatment efficacy.

Previous studies have reported that miR-3681-3p is

downregulated in lung adenocarcinoma and is associated with

aggressive behaviors (61,62). However, the role and mechanism of

miR-3681-3p in gastric cancer remain poorly understood. The present

study revealed that exosomes derived from M2-polarized macrophages

contributed to DDP resistance in gastric cancer cells, with a

significant elevation of miR-3681-3p in these exosomes.

Furthermore, miR-3681-3p mimic transfection significantly reduced

the sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to DDP, resulting in an

increased IC50 value. These findings offer new insights

into the key role of exosomes from M2-polarized macrophages in

regulating cancer progression and highlight the novel function of

miR-3681-3p in gastric cancer. The association between exosomal

miR-3681-3p from M2 macrophages and its role in mediating drug

resistance is an important scientific question that warrants

further investigation. Understanding the mechanisms by which

elevated miR-3681-3p contributes to DDP resistance in gastric

cancer cells is essential for developing effective therapeutic

interventions.

The MLH1 gene has a key role in maintaining genomic

integrity through the mismatch repair mechanism, correcting errors

during DNA replication (63).

Deficiency or loss of MLH1 is associated with the initiation and

progression of various types of cancer (64–66).

Specifically, in colorectal carcinoma, MLH1-proficient cells were

revealed to be less sensitive to 5-FU-induced cytotoxic effects

(64). Moreover, MLH1 deficiency

is associated with cetuximab resistance in colon cancer due to

activation of the Her-2/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (65). Notably, negative MLH1 expression

was previously detected in 9.8% (28/285) of patients with gastric

cancer, and was associated with chemoresistance and resulted in no

improvement in survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (67). The present study revealed that

miR-3681-3p directly targets MLH1. MLH1 downregulation

significantly diminished the sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to

DDP, as evidenced by an increased IC50 value. By

contrast, the overexpression of MLH1 effectively reversed the DDP

resistance of AGS cells caused by miR-3681-3p mimic treatment, as

indicated by the decrease in the IC50 value. These

results confirmed that miR-3681-3p may directly target MLH1.

Mechanistically, high levels of miR-3681-3p in exosomes from

M2-polarized macrophages may promote DDP resistance by

downregulating MLH1 expression. However, MLH1 is likely one of

multiple targets of miR-3681-3p, suggesting the need for further

investigation into additional regulatory factors involved in this

pathway.

While the findings of the present study provided

insights into the miR-3681-3p/MLH1 axis as a potential therapeutic

target in gastric cancer, this study has some limitations. The

interactions between miR-3681-3p and MLH1 require further

validation through additional experiments. Moreover, the findings

were derived exclusively from the AGS cell line, necessitating

corroboration across diverse cancer cell lines to enhance their

applicability. Future studies should also include animal models to

comprehensively elucidate the role of the miR-3681-3p/MLH1 axis in

gastric cancer treatment.

In conclusion, exosomal miR-3681-3p from M2

macrophages may contribute to DDP resistance in gastric cancer

cells by suppressing MLH1 expression. The miR-3681-3p/MLH1 axis

could be a promising molecular target for developing new

therapeutic strategies for gastric cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Scientific Research

Project of High-Level Talents of Affiliated Hospital of Youjiang

Medical University for Nationalities (grant no. R202011710), the

Scientific Research Project of Young and Middle-Aged Key Talents of

Affiliated Hospital of Youjiang Medical University for

Nationalities (grant no. Y20212603), the Project of Open Subject of

Guangxi Key Laboratory of Molecular Pathology of Hepatobiliary

Diseases of Affiliated Hospital of Youjiang Medical University for

Nationalities (grant no. GXZDSYS-009), the Project of Scientific

Research and Technology Development Plan of Baise City (grant nos.

Encyclopedia 20213301, Encyclopedia 20213242, Encyclopedia

20232080), Self-Funded Scientific Research Projects of Guangxi

Health and Health Commission (grant nos. Z20211114 and Z20190202),

Self-Funded Scientific Research Projects of the Administration of

Traditional Chinese Medicine of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous

Region (grant no. GXZYL20220304) and Scientific Research Basic

Ability Enhancement Project for Young and Middle-Aged Teachers of

Guangxi Colleges And Universities (grant no. 2021KY0538).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WJW and ZYC conceptualized and designed the study.

WJW, JXL, CL and RTH engaged in the acquisition, analysis and

interpretation of the data. JJH, QJ and JZW contributed to the

interpretation of the data, along with manuscript drafting and

finalization. QL and GDX performed the formal analysis. ZYC secured

funding. WJW and ZYC confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The protocol of the present study was approved by

the Medical Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Youjiang

Medical University for Nationalities (approval no.

YYFY-LL-2024-283).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ricci AD, Rizzo A and Brandi G: DNA damage

response alterations in gastric cancer: Knocking down a new wall.

Future Oncol. 17:865–868. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

López MJ, Carbajal J, Alfaro AL, Saravia

LG, Zanabria D, Araujo JM, Quispe L, Zevallos A, Buleje JL, Cho CE,

et al: Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 181:1038412023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Guggenheim DE and Shah MA: Gastric cancer

epidemiology and risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 107:230–236. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yang K, Lu L, Liu H, Wang X, Gao Y, Yang

L, Li Y, Su M, Jin M and Khan S: A comprehensive update on early

gastric cancer: Defining terms, etiology, and alarming risk

factors. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 15:255–273. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van

Grieken NC and Lordick F: Gastric cancer. Lancet. 396:635–648.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Song Z, Wu Y, Yang J, Yang D and Fang X:

Progress in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Tumour Biol.

39:10104283177146262017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Patel TH and Cecchini M: Targeted

therapies in advanced gastric cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol.

21:702020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ricci AD, Rizzo A, Rojas Llimpe FLR, Di

Fabio F, De Biase D and Rihawi K: Novel HER2-directed treatments in

advanced gastric carcinoma: AnotHER paradigm shift? Cancers

(Basel). 13:16642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rao X, Zhang C, Luo H, Zhang J, Zhuang Z,

Liang Z and Wu X: Targeting gastric cancer stem cells to enhance

treatment response. Cells. 11:28282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bilotta MT, Antignani A and Fitzgerald DJ:

Managing the TME to improve the efficacy of cancer therapy. Front

Immunol. 13:9549922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Bejarano L, Jordāo MJC and Joyce JA:

Therapeutic targeting of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov.

11:933–959. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rizzo A, Santoni M, Mollica V, Logullo F,

Rosellini M, Marchetti A, Faloppi L, Battelli N and Massari F:

Peripheral neuropathy and headache in cancer patients treated with

immunotherapy and immuno-oncology combinations: The MOUSEION-02

study. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 17:1455–1466. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xia Y, Rao L, Yao H, Wang Z, Ning P and

Chen X: Engineering macrophages for cancer immunotherapy and drug

delivery. Adv Mater. 32:e20020542020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena

P and Sica A: Macrophage polarization: Tumor-associated macrophages

as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends

Immunol. 23:549–555. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hu X, Ma Z, Xu B, Li S, Yao Z, Liang B,

Wang J, Liao W, Lin L, Wang C, et al: Glutamine metabolic

microenvironment drives M2 macrophage polarization to mediate

trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive gastric cancer. Cancer

Commun (Lond). 43:909–937. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shi Q, Shen Q, Liu Y, Shi Y, Huang W, Wang

X, Li Z, Chai Y, Wang H, Hu X, et al: Increased glucose metabolism

in TAMs fuels O-GlcNAcylation of lysosomal Cathepsin B to promote

cancer metastasis and chemoresistance. Cancer Cell.

40:1207–1222.e10. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kalluri R and LeBleu VS: The biology,

function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science.

367:eaau69772020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yang Y, Guo Z, Chen W, Wang X, Cao M, Han

X, Zhang K, Teng B, Cao J, Wu W, et al: M2 macrophage-derived

exosomes promote angiogenesis and growth of pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma by targeting E2F2. Mol Ther. 29:1226–1238. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Xu M, Zhou C, Weng J, Chen Z, Zhou Q, Gao

J, Shi G, Ke A, Ren N, Sun H and Shen Y: Tumor associated

macrophages-derived exosomes facilitate hepatocellular carcinoma

malignance by transferring lncMMPA to tumor cells and activating

glycolysis pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 41:2532022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

O'Brien K, Breyne K, Ughetto S, Laurent LC

and Breakefield XO: RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in

mammalian cells and its applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

21:585–606. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhao S, Mi Y, Guan B, Zheng B, Wei P, Gu

Y, Zhang Z, Cai S, Xu Y, Li X, et al: Tumor-derived exosomal

miR-934 induces macrophage M2 polarization to promote liver

metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 13:1562020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Han S, Bao X, Zou Y, Wang L, Li Y, Yang L,

Liao A, Zhang X, Jiang X, Liang D, et al: d-lactate modulates M2

tumor-associated macrophages and remodels immunosuppressive tumor

microenvironment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Adv.

9:eadg26972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gao J, Liang Y and Wang L: Shaping

polarization of tumor-associated macrophages in cancer

immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 13:8887132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hu Q, Yao J, Wu X, Li J, Li G, Tang W, Liu

J and Wan M: Emodin attenuates severe acute pancreatitis-associated

acute lung injury by suppressing pancreatic exosome-mediated

alveolar macrophage activation. Acta Pharm Sin B. 12:3986–4003.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Rehmsmeier M, Steffen P, Hochsmann M and

Giegerich R: Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target

duplexes. RNA. 10:1507–1517. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu C, Li S and Tang Y: Mechanism of

cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer and associated microRNAs.

Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 92:329–340. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang Q, Huang C, Wang D, Tao Z, Zhang H,

Zhao Y, Wang M, Zhou C, Xu J, Shen B and Zhu W: Gastric cancer

derived mesenchymal stem cells promoted DNA repair and cisplatin

resistance through up-regulating PD-L1/Rad51 in gastric cancer.

Cell Signal. 106:1106392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hou G, Bai Y, Jia A, Ren Y, Wang Y, Lu J,

Wang P, Zhang J and Lu Z: Inhibition of autophagy improves

resistance and enhances sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to

cisplatin. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 98:449–458. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Peng L, Sang H, Wei S, Li Y, Jin D, Zhu X,

Li X, Dang Y and Zhang G: circCUL2 regulates gastric cancer

malignant transformation and cisplatin resistance by modulating

autophagy activation via miR-142-3p/ROCK2. Mol Cancer. 19:1562020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Baba H, Takeuchi H, Inutsuka S, Yamamoto

M, Endo K, Ohno S, Maehara Y and Sugimachi K: Clinical value of SDI

test for predicting effect of postoperative chemotherapy for

patients with gastric cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 10:140–144. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chen SH and Chang JY: New insights into

mechanisms of cisplatin resistance: From tumor cell to

microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 20:41362019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yan XY, Qu XZ, Xu L, Yu SH, Tian R, Zhong

XR, Sun LK and Su J: Insight into the role of p62 in the cisplatin

resistant mechanisms of ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell Int.

20:1282020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang S, Li MY, Liu Y, Vlantis AC, Chan JY,

Xue L, Hu BG, Yang S, Chen MX, Zhou S, et al: The role of microRNA

in cisplatin resistance or sensitivity. Expert Opin Ther Targets.

24:885–897. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Bellmunt J, Pons F and Orsola A: Molecular

determinants of response to cisplatin-based neoadjuvant

chemotherapy. Curr Opin Urol. 23:466–471. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Misumi T, Tanabe K, Fujikuni N and Ohdan

H: Stimulation of natural killer cells with rhCD137 ligand enhances

tumor-targeting antibody efficacy in gastric cancer. PLoS One.

13:e02048802018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Olsen LC and Færgeman NJ: Chemical

genomics and emerging DNA technologies in the identification of

drug mechanisms and drug targets. Curr Top Med Chem. 12:1331–1345.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lill JR, Mathews WR, Rose CM and Schirle

M: Proteomics in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry: A

look to the next decade. Expert Rev Proteomics. 18:503–526. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Dinić J, Efferth T, Garcia-Sosa AT,

Grahovac J, Padrón JM, Pajeva I, Rizzolio F, Saponara S, Spengler G

and Tsakovska I: Repurposing old drugs to fight multidrug resistant

cancers. Drug Resist Updat. 52:1007132020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Brewer JR, Chang E, Agrawal S, Singh H,

Suzman DL, Xu J, Weinstock C, Fernandes LL, Cheng J, Zhang L, et

al: Regulatory considerations for contribution of effect of drugs

used in combination regimens: Renal cell cancer case studies. Clin

Cancer Res. 26:6406–6411. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Biankin AV, Piantadosi S and Hollingsworth

SJ: Patient-centric trials for therapeutic development in precision

oncology. Nature. 526:361–370. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Mahomed S, Padayatchi N, Singh J and

Naidoo K: Precision medicine in resistant Tuberculosis: Treat the

correct patient, at the correct time, with the correct drug. J

Infect. 78:261–268. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Yang C, Deng X, Tang Y, Tang H and Xia C:

Natural products reverse cisplatin resistance in the hypoxic tumor

microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 598:2171162024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Otvos L: The latest trends in peptide drug

discovery and future challenges. Expert Opin Drug Discov.

19:869–872. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Asaoka Y, Ikenoue T and Koike K: New

targeted therapies for gastric cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs.

20:595–604. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liu L, Wu N and Li J: Novel targeted

agents for gastric cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 5:312012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Portilla LM, Evans G, Eng B and Fadem TJ:

Advancing translational research collaborations. Sci Transl Med.

2:63cm302010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Munoz-Sanjuan I and Bates GP: The

importance of integrating basic and clinical research toward the

development of new therapies for Huntington disease. J Clin Invest.

121:476–483. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Li M, Yang Y, Xiong L, Jiang P, Wang J and

Li C: Metabolism, metabolites, and macrophages in cancer. J Hematol

Oncol. 16:802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Chen S, Saeed AFUH, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Xu H,

Xiao GG, Rao L and Duo Y: Macrophages in immunoregulation and

therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:2072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Locati M, Curtale G and Mantovani A:

Diversity, mechanisms, and significance of macrophage plasticity.

Annu Rev Pathol. 15:123–147. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wang S, Liu R, Yu Q, Dong L, Bi Y and Liu

G: Metabolic reprogramming of macrophages during infections and

cancer. Cancer Lett. 452:14–22. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wang HC, Haung LY, Wang CJ, Chao YJ, Hou

YC, Yen CJ and Shan YS: Tumor-associated macrophages promote

resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells against sorafenib by

activating CXCR2 signaling. J Biomed Sci. 29:992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhang G, Tao X, Ji B and Gong J:

Hypoxia-driven M2-polarized macrophages facilitate cancer

aggressiveness and temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma. Oxid

Med Cell Longev. 2022:16143362022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Huang J, Pan H, Sun J, Wu J, Xuan Q, Wang

J, Ke S, Lu S, Li Z, Feng Z, et al: TMEM147 aggravates the

progression of HCC by modulating cholesterol homeostasis,

suppressing ferroptosis, and promoting the M2 polarization of

tumor-associated macrophages. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:2862023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ngabire D, Niyonizigiye I, Patil MP, Seong

YA, Seo YB and Kim GD: M2 macrophages mediate the resistance of

gastric adenocarcinoma cells to 5-fluorouracil through the

expression of integrin β 3, focal adhesion kinase, and cofilin. J

Immunol Res. 2020:17314572020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Li J, Bao Y, Peng S, Jiang C, Zhu L, Zou

S, Xu J and Li Y: M2 macrophages-derived exosomal miRNA-23a-3p

promotes the progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma by

targeting PTEN. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 45:4936–4947. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Tian B, Zhou L, Wang J and Yang P:

miR-660-5p-loaded M2 macrophages-derived exosomes augment

hepatocellular carcinoma development through regulating KLF3. Int

Immunopharmacol. 101:1081572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Cui HY, Rong JS, Chen J, Guo J, Zhu JQ,

Ruan M, Zuo RR, Zhang SS, Qi JM and Zhang BH: Exosomal microRNA-588

from M2 polarized macrophages contributes to cisplatin resistance

of gastric cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 27:6079–6092. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang B, Cai Y, Li X, Kong Y, Fu H and Zhou

J: ETV4 mediated lncRNA C2CD4D-AS1 overexpression contributes to

the malignant phenotype of lung adenocarcinoma cells via

miR-3681-3p/NEK2 axis. Cell Cycle. 20:2607–2618. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zhu MC, Zhang YH, Xiong P, Fan XW, Li GL

and Zhu M: Circ-GSK3B up-regulates GSK3B to suppress the

progression of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 29:1761–1772.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

DuPrie ML, Palacio T, Calil FA, Kolodner

RD and Putnam CD: Mlh1 interacts with both Msh2 and Msh6 for

recruitment during mismatch repair. DNA Repair (Amst).

119:1034052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Manzoor S, Saber-Ayad M, Maghazachi AA,

Hamid Q and Muhammad JS: MLH1 mediates cytoprotective nucleophagy

to resist 5-fluorouracil-induced cell death in colorectal

carcinoma. Neoplasia. 24:76–85. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Han Y, Peng Y, Fu Y, Cai C, Guo C, Liu S,

Li Y, Chen Y, Shen E, Long K, et al: MLH1 deficiency induces

cetuximab resistance in colon cancer via her-2/PI3K/AKT signaling.

Adv Sci (Weinh). 7:20001122020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Scarpa M, Ruffolo C, Kotsafti A, Canal F,

Erroi F, Basato S, DallAgnese L, Fiorot A, Pozza A, Brun P, et al:

MLH1 deficiency down-regulates TLR4 expression in sporadic

colorectal cancer. Front Mol Biosci. 8:6248732021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Hashimoto T, Kurokawa Y, Takahashi T,

Miyazaki Y, Tanaka K, Makino T, Yamasaki M, Nakajima K, Ikeda JI,

Mori M and Doki Y: Predictive value of MLH1 and PD-L1 expression

for prognosis and response to preoperative chemotherapy in gastric

cancer. Gastric Cancer. 22:785–792. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|