Introduction

Plastics are widely used in modern society; every

year ~320 tons of plastics are manufactured globally (1). Plastics are used in a wide range of

applications, including packaging materials, construction,

automotive parts, electronics, medical devices, textiles and

consumer goods, due to their versatility, durability and

cost-effectiveness. These plastic products are usually resistant to

high temperature, acid, alkali and corrosion and have the benefit

of convenience due to their lightweight nature, ease of

manufacturing, versatility and cost-effectiveness in various

applications. However, there is no efficient and feasible method

for plastic degradation, which results in notable environmental

issues. The most common plastic pollutants in the environment

include polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride, polypropylene,

polyethylene terephthalate and polystyrene (2). In the natural environment, these

plastics are rarely completely degraded by microbiological

activity, radiation and mechanical stress, leading to

disintegration and fragmentation of larger plastic items into

smaller particles; transfer and diffusion are more likely to occur,

resulting in microplastic (MP) pollution of the environment.

Plastic particles are divided into MPs with diameter

<5 mm and nano-plastics (NPs) with diameter <1 µm. MPs are

found in a range of environmental domains, including air, fresh

water, soil and oceans (3). MPs

are released in numerous ways, for example as microfibers from

textiles during washing and from synthetic textiles, personal care

products, synthetic rubber tire erosion and industrial production.

After a series of environmental processes such as decomposition and

migration, they enter animals and plants, and enter the human body

via inhalation, ingestion and skin contact (4). Ingestion of MPs or plastic

derivatives such as chemical additives can cause a variety of

toxicological effects, including growth inhibition, metabolic

disorder, inflammatory response, reproductive problems and

mortality (5,6).

Studies have found MPs and NPs are present in human

blood, placenta and feces (7–9). The

ingestion of MPs is a prevalent route of exposure, with MPs being

detected in food and beverages such as seafood, drinking water and

beer (4). Exposure models in mice

have shown that MPs and NPs accumulate in the stomach, intestine,

liver and other organs (10,11).

Due to the high corrosion resistance of MPs and NPs entering into

the digestive tract, digestive fluid changes the surface roughness

and particle size of MPs and NPs, making them more stable in the

lining of the digestive tract and more prone to adsorption of toxic

substances (12). The barriers

within the tissues do not prevent invasion of MPs and NPs. After

MPs and NPs enter the body, small plastic particles can cross the

epithelial barrier of the digestive system (13–15)

and enter the lymphatic and blood circulation. For example, NPs

with a size of 0.1–10 µm cross the blood-brain barrier and the

placenta (16–18). Ingested MPs and NPs with a particle

size >150 µm pass through the intestinal epithelial cells with

difficulty, resulting in ~90% of MPs being excreted through feces,

with the rest having a localized effect outside the intestinal

epithelial cell membranes. When nanosized plastic particles with

diameter <150 µm come into contact with the villi of the small

intestine, they pass through the small intestinal epithelial cells

(19), enter the lymphatic system

(20) and bloodstream (21), and reach the portal vein through

the capillaries and are spread throughout the body (22–24).

NPs with diameter <150 and >10 µm reach other organs and cell

membranes (17), while those with

a size of <5 µm are absorbed by lymphocytes (19). Smaller nanoparticles diffuse into

the bloodstream via bypass of intercellular tight junctions

(25). Mucus secreted by the

intestinal epithelial cup cells promotes bypass diffusion of the

nanoparticles (19). Larger

nanoparticles (diameter, 50–200 nm) tend to cross intestinal

epithelial cells by endocytosis; 40 nm diameter may be the optimal

size for non-phagocytic uptake (26), while 200 nm may be the optimal size

for crossing the blood-brain barrier (27). In vivo studies have found

that intestinal cells internalize nanoscale particulate matter

using different endocytosis mechanisms; additionally phagocytes can

internalize them through phagocytosis (28), whereas non-phagocytes internalize

smaller nanoparticles with the help of lattice proteins or

cell-membrane-invasion-mediated endocytosis (25), in which actin serves an important

role (29). In addition,

energy-dependent pathways serve a key role in the mechanisms of

endocytosis in intestinal epithelial cells (29). NPs smaller than 3 µm can be

internalized into non-phagocytic cells via non-specific endocytosis

(29), while the maximum particle

size available for endocytosis increases to 5 µm (19), facilitated by the abundant M cells

in the intestinal Peyer's patches (21) and aided by the intestinal mucosal

membranes (30,31). The strong electrostatic interaction

between positively charged particles and the plasma membrane

increases surface tension, which subsequently reduces the

membrane's elasticity (32),

facilitating NPs internalization and their entry into the

bloodstream. In addition to NPs absorbed by the digestive tract,

inhaled MPs and NPs remain in the lungs or enter the circulatory

system through capillaries; particles with a size of <2.5 µm

enter the circulation or penetrate the alveoli (33). NPs that enter the circulation

(diameter, ~100 nm) are surrounded by serum albumin (34), forming a multilayered serum albumin

crown, which may help the NPs evade immune surveillance, increase

their time in the circulatory system and help the particles reach

secondary organs and accumulate in the liver, kidneys and

intestines (34). The binding of

serum albumin to NPs leads to changes in the secondary structure of

the protein (35), which increases

cytotoxicity of the plastic particles.

Although only a small percentage of NPs penetrate

the epithelial barrier of alveolar and gastrointestinal tracts, and

transfer into secondary tissues and organs (9), this low rate of internalization may

have considerable consequences due to long-term exposure of humans

to plastic particles and the potential of accumulation; harmful

effects include oxidative stress, local inflammation, cellular

apoptosis and alteration of intestinal flora (36–39).

An in vivo study showed that following MP ingestion by mice,

interaction between Helicobacter pylori and MPs in the

stomach promoted the rapid colonization of H. pylori in the

epithelial cells of the gastric mucosa (10); proliferation of this pathogenic

bacterium leads to stomach inflammation in the mice. In several

in vivo studies, MPs were found to cause intestinal flora

disorders in mice, with an increase in number of conditionally

pathogenic bacteria, accompanied by intestinal inflammation

(40–42). The effects of NPs on the liver

mainly include disruption of glycolipid metabolism, with an

increase in glucose and diabetes mellitus in NP-exposed mice

(43) and a decrease in hepatic

fat, triglycerides and total cholesterol (44). An in vitro study has found

that NPs enter cells and lead to injury effects (45). Co-culture of human gastric mucosal

epithelial cells with NPs results in decreased proliferation and

increased apoptosis (46). NPs

cause oxidative stress in human intestinal cells (47).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies

investigating whether MPs and NPs pass through the food chain to

the human body; however, in vitro and ex vivo studies

reveal the adverse effects of MPs and NPs in the human body

(4,8,9).

Investigating the mechanism of injury effects of MPs and NPs is key

for understanding the impact of MPs and NPs on health, as well as

for prevention and treatment of MP- and NP-induced health

problems.

The present review discusses the mechanisms by which

MPs and NPs damage the human gastrointestinal tract and liver and

limitations of existing research and suggests future research

directions to provide a scientific foundation for investigation of

the effects and mechanisms of MPs and NPs on the human body.

Literature search

A comprehensive online search using PubMed

(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/),

Embase (https://www.embase.com/), the Cochrane

Library (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/) and the

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) was performed from their

inception to January 2024 with the following MeSH and EMTREE

keywords: ‘Micro-plastics’, ‘nano-plastics’, ‘gastrointestinal

disease’, ‘liver/hepatic metabolism’, ‘MPs’, ‘NPs’ and ‘digestive

diseases’. All published studies associated with MPs and/or NPs,

gastrointestinal disease or liver metabolism were included. Studies

were excluded if they did not focus on MPs and/or NPs in the

context of gastrointestinal diseases or liver metabolism, or if

they were not published in peer-reviewed journals. Two independent

investigators conducted the literature searches and eligibility

assessment, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus and

consultation with a third reviewer.

Mechanism of oxidative stress, inflammation

and apoptosis in the gastrointestinal tract

MPs and NPs enter cells through endocytosis

mechanisms or become adsorbed and accumulate on the surface of

gastrointestinal tissue, causing oxidative stress, inflammation and

apoptosis (Tables I and II). Therefore, it is important to

investigate the mechanism underlying injury effects of MPs and NPs

on the gastrointestinal tract to provide a scientific basis for

prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal diseases caused by MPs

and NPs.

| Table I.Injury effects and mechanism of

microplastics and nano-plastics in vivo in mice. |

Table I.

Injury effects and mechanism of

microplastics and nano-plastics in vivo in mice.

|

|

| Microplastic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Organ | Mouse strain | Type | Size, µm | Exposure route | Dosage | Biomarker | Effect | Mechanism | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Stomach | Balb/c | PE | 10-150 | Intragastric

administration (3 times, 1 week) | 100 µg/ml | IL6, MPO and

TNF-α | Rapid colonization

of Helicobacter pylori in gastric mucosal epithelial cells,

gastric injury and inflammation | Increased

expression of myeloperoxidase, IL-6 and TNF-α | (10) |

| Liver, colon, ileum

and cecum | ICR | PS | 5 | Water consumption

for ~6 weeks | 100, 1,000

µg/l | TG, PYR, TCH, GLU,

HDL-C, LDL-C, CPT1, CPT2 | Disorder of lipid

metabolism, intestinal shielding dysfunction | Changes in

intestinal flora | (11) |

| Colon and

duodenum | C57BL/6 | PE | 10-150 | Consumption of

MP-enriched feed for 5 weeks | 6, 60, 600

µg/day | IL-1α, G-CSF, IL-2,

IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IP-10 and RANTES | Intestinal

inflammation | Upregulation of

IL-1α, TLR4, AP-1 and IRF5, changes in intestinal

flora, immune imbalance | (40) |

| Colon | C57BL/6 | PS | 5 | Water consumption

for 28 days | 500 µg/day | TNF-α, IL-1β and

IL-6 | Impaired intestinal

barrier and intestinal inflammation, increased intestinal

pathogenic bacteria, interference with intestinal microbial

metabolism | Immune imbalance,

changes in intestinal flora, upregulation of inflammatory factors

(TNF-α, IL-1β and IFN-γ) | (41) |

| Intestines and

cecum | CD-1 | PE | 45-53 | Oral gavage daily

for 30 days | 5.24×104

particles/day | DAO, D-Lac | Increased

intestinal permeability, intestinal inflammation, metabolic

disorder | Changes in

composition of intestinal flora, decreased abundance of bacteria

associated with energy metabolism and immune function;

downregulation of genes associated with oxidative stress, immune

response and lipid metabolism | (42) |

| Liver and

intestine | ICR | PS | 1 | Water consumption

for 1–2 weeks | 55 µg/d | CAT, SOD,

GSH-Px | Insulin resistance,

diabetes mellitus | Metabolic crosstalk

of gut-liver axis | (43) |

| Liver, colon,

ileum | ICR | PS | 5 | Water consumption

for 6 weeks | 100, 1,000

µg/l | TG, TCH, PYR, TBA,

CFTR and NKCC1 | Decreased secretion

of intestinal mucus, damage to intestinal barrier function,

dysbiosis of the gut microbiome and metabolic disorder | NR | (44) |

| Liver and

cecum | ICR | PS | 0.5 and 50 | Water consumption

for 5 weeks | 100, 1,000

µg/l | TG, TCH, GLU,

TBA | Decreased liver

weight, secretion of intestinal mucus, TG and TCH levels and

hepatic lipid disorder | Changes in

intestinal flora, decreased mRNA levels of genes involved in the

synthesis of fats and TG in the liver | (63) |

| Liver | C57BL/6J | PS | 0.5 | Water consumption

for 28 days | 0.5 mg/day | AST, ALB, ALT,

TBIL | Affect the liver

immune microenvironment, hepatic inflammation | Increased immune

infiltration of NK cells and macrophages and decreased immune

infiltration of B cells, increased expression of ALT and aspartate

aminotransferase, activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway | (85) |

| Intestine and

colon | C57/B6 | PS | 5 | Water consumption

for 28 days | 0.2 mg/kg | ZO-1,

claudin-1-3 | Intestinal barrier

dysfunction, increased opportunistic pathogens and decreased tight

junction promoting functional microorganisms | Downregulation of

tight junction protein expression, changes in intestinal flora | (86) |

| Table II.Injury effects and mechanism of

microplastics and nano-plastics in human cells. |

Table II.

Injury effects and mechanism of

microplastics and nano-plastics in human cells.

|

| Microplastic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

| Dosage, Cell | Duration of

Type |

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Size | µg/ml | exposure | Biomarkers | Effects | Mechanism | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Human colon

adenocarcinoma Caco-2, HT29-MTX | PS | 25 and 100 nm | 0-200;

0.01–100 | 4 h | LDH, ROS | Decreased cell

viability, oxidative stress, inflammation, mitochondrial

apoptosis | Upregulation of

HSP70, HO1 and IL- 1β, increased mitochondrial membrane

potential | (15,52) |

| Liver organoids H1

ES | PS | 1 µm | 0.25–25 | 48 h | LDH, ATP, CYP3A4

activity, COL1A1, IL-6, ALT, AST, TG, GSH, GST, SOD | Disrupted function

of metabolic enzymes, increased lipid accumulation, ROS production,

oxidative stress and inflammatory response, hepatotoxicity | Increased release

of ASL and ALT, gene expression associated with disrupt liver

function, expression of HNF4A, CYP2EI, IL-6 and

COL1AI | (39) |

| Human gastric

mucosal epithelial GES-1 | PS | NR | 100 | 24 h | RhoA, Rac1,

F-actin, Rab5, RAB7, LAMP1, LC3B II | Decreased cell

proliferation rate, increased apoptosis | NR | (46) |

| Human colon

adenocarcinoma Caco-2 | PS | 50 nm | 100 | 24 h; 8 weeks | ROS, HO1, GSTP1,

HSP70, SOD2 | Oxidative

stress | HO1 and

SOD 2 transcript levels were significantly increased | (47) |

| Human gastric

adenocarcinoma CRL1739 | PS | 100, | 0.1–100 44 nm | 1 h | c-Myc, ERK-1, Ki67,

CCNE1, CCND1, p38, p53, IL8, IL6, IL-1β, TGF-β1, NF-κB1, HPTR1 | Decreased cell

viability and morphology and inflammation | Upregulation of

IL-6 and IL-8 | (58) |

| Human gastric

carcinoma AGS | PS | 60 and 500 nm | 0.1–100 | 24 h | ROS, apoptotic

protein | Decreased cell

viability; increased apoptosis or necrosis | Disruption of cell

membrane integrity, upregulation of Bax, increased

expression of Caspase-3 and Caspase-8 | (60) |

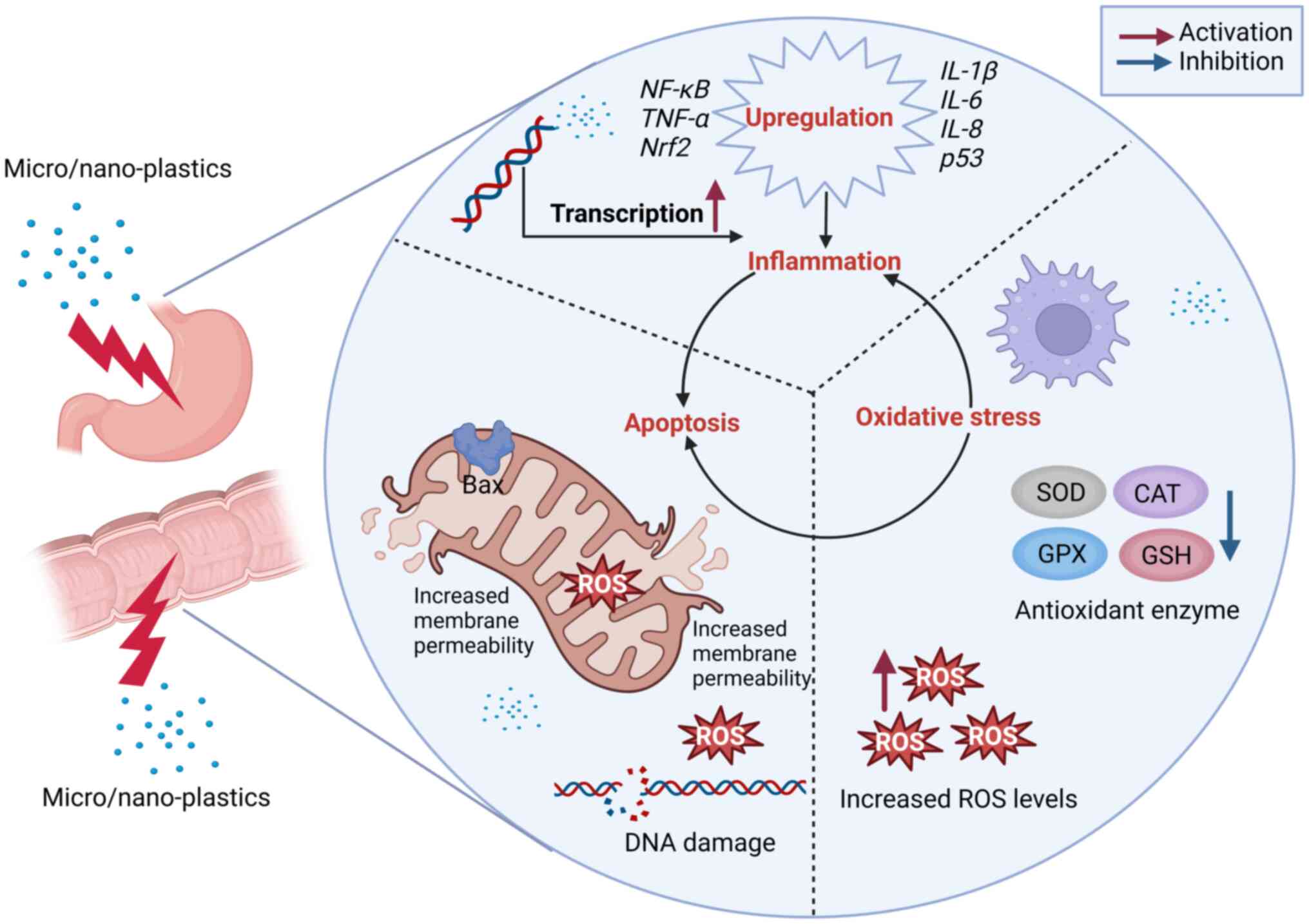

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells

induce generation of oxidative stress

Cells possess an antioxidant defense system that

maintains intracellular ROS levels and protects biomolecules from

free radical damage (48,49). Increased ROS and oxidative stress

in cells are associated with antioxidant system imbalance and

disease (50). In vitro and

in vivo studies have shown that MPs and NPs increase

intracellular ROS levels (16,31).

The direct stimulatory effect of exogenous particles increases

intracellular ROS production (51). However, MPs and NPs inhibit

production of antioxidant enzyme transcription factors or decrease

activity of antioxidant enzymes, which in turn inhibits ROS

metabolism and increases mitochondrial membrane potential resulting

in an increase in mitochondrial permeability and ROS production,

thus increasing mitochondrial ROS production; this increases

transfer of ROS produced in mitochondria to the cytoplasm (52). Superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase

(CAT) and glutathione (GSH) are key biomarkers for measuring the

degree of oxidative stress. Polystyrene NPs can lead to increased

levels of peroxidative biomarkers and markedly decreased SOD, CAT

activity and GSH in the duodenum of mice (53,54);

in vitro experiment using human normal colonic mucosal

epithelial cells has revealed that ROS levels in NP-treated cells

are increased compared with those in untreated cells (53). Therefore, MPs and NPs directly

promote ROS production or indirectly inhibit ROS metabolism by

inhibiting antioxidant enzyme activity and GSH production, leading

to an increase in ROS (Fig. 1). As

MPs and NPs interact with the cellular microenvironment, increased

ROS settle on the surface of MPs and NPs, leading to oxidative

stress in the cell, which induces localized inflammation in the gut

if MPs and NPs are unable to cross the cellular membrane (55); if the particles are small enough to

cross the intestinal epithelium, ROS toxicity on the surface of

particles is enhanced, mediating a stress response in cells

(56).

Underlying mechanisms of

inflammation

Following ingestion, MPs and NPs accumulate in the

gastrointestinal tract. Mechanical damage or stimulation induced by

MPs and NPs causes inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract

(10,40) due to release of proinflammatory

cytokines (10) or imbalance of

intestinal flora, causing an increase in conditionally pathogenic

bacteria and resulting in immune imbalance and an increase in

lipopolysaccharide content (42,57).

MPs and NPs induce proinflammatory cytokine release

via direct stimulation of proinflammatory cytokine production. An

in vivo study revealed that elevated IL-6 and TNF-α promote

gastric injury and inflammation (10). In vitro studies reveal that

expression of proinflammatory genes such as IL-1β, −6 and −8 is

increased in MP- and NP-treated gastric and small intestinal

epithelial cells, resulting in increased release of proinflammatory

cytokines (15,58). Another mechanism involves oxidative

stress promoting inflammation by activating transcription factors

such as NF-κB, p53, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

(PPAR)-γ and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (59), which regulate the expression of

inflammatory cytokines and thus increase release of proinflammatory

cytokines (Fig. 1).

In vivo studies have shown that MPs and NPs

lead to gastrointestinal tract injury in mice (9,15–17).

MPs and NPs promote rapid colonization of H. pylori on the

epithelial cell surface of the gastric mucosa, increase the

efficiency with which NPs enter tissues and promote inflammation

(10). MPs and NPs cause

intestinal dysbiosis, a marked decrease in abundance of immune

function-associated bacteria (42), an increase in the number of

pathogenic bacterial colonies and a decrease in the number of

CD4+ T helper 17 and regulatory T cells, leading to an

immune imbalance, as well as an increase in plasma

lipopolysaccharides (57), which

stimulate intestinal inflammation (41).

Potential mechanisms of apoptosis

Both endogenous and exogenous factors contribute to

DNA damage, and NPs can cross the nuclear membrane, directly

inducing DNA damage (52). In

addition, oxidative stress caused by increased intracellular ROS

levels due to MPs and NPs can lead to DNA damage. If DNA damage is

not repaired rapidly, apoptosis is induced (59). Apoptosis induced by oxidative

stress is observed in in vitro studies (15,60),

accompanied by an increase in mitochondrial membrane potential

(Fig. 1). A study using HaCaT

cells found that under conditions simulating oxidative stress in

vitro, an increase in intracellular expression of inverted

formin-2 leads to ROS overload in mitochondria, which disrupts

cellular redox balance, alters mitochondrial membrane potential,

causes mitochondrial stress and inhibits the hypoxia inducible

factor-1 signaling pathway to mediate apoptosis (61). Bax, a member of the Bcl-2 family,

regulates the release of apoptosis-inducing factors and the

permeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane, with its

overexpression potentially triggering apoptosis (60). Increased expression of Bax

increases permeability of the mitochondrial membrane, leading to

the release of apoptosis-inducing factors from the mitochondria

into the cytoplasm, activating cysteoaspartic enzymes and leading

to apoptosis. N-terminal acetylation of Bax is involved in its

mitochondrial targeting; increase in expression of the Bax

gene leads to an increase in permeability of the mitochondrial

membrane, which results in the release of ROS from the

mitochondria; this leads to ROS accumulation in cells, triggering

apoptosis (Fig. 1). In addition,

the inflammatory response caused by MPs and NPs triggers

apoptosis.

In summary, increased ROS production or decreased

ROS metabolism leads to accumulation of intracellular ROS resulting

in DNA damage and oxidative stress. Immune imbalance caused by

gastrointestinal flora dysbiosis and increased expression of

inflammation-associated cytokines lead to inflammation. Oxidative

stress and inflammation lead to apoptosis. MPs and NPs overexpress

pro-apoptosis-related genes, directly leading to apoptosis

(Fig. 1).

Mechanism of liver glucose and lipid

metabolism disorder

The liver is a key detoxification organ in the human

body. MPs and NPs accumulate on the surface of epithelial cells in

the gastrointestinal tract following ingestion. NPs are absorbed by

epithelial cells and they then enter the lymphatic and blood

circulation, arriving at the liver through the portal vein

(62). Study has also found that

NPs disturb the glucose-lipid metabolism of liver tissues (63), and similar toxic effects have been

detected in an in vitro study of human liver-like organs.

Toxic effects of NPs were also found in in vitro human

liver-like organs (6). Previous

biochemical and transcriptomics studies have investigated the

injury mechanism of NPs causing disruption of glycolipid metabolism

in liver tissue (11,43,57)

and found that NPs affect glycolipid metabolism at both biochemical

and transcriptional levels. NPs cause injury due to effects on

intermediate glycolipid metabolism at the biochemical level and

production of key rate-limiting enzymes in glycolipid metabolism at

the transcriptional level.

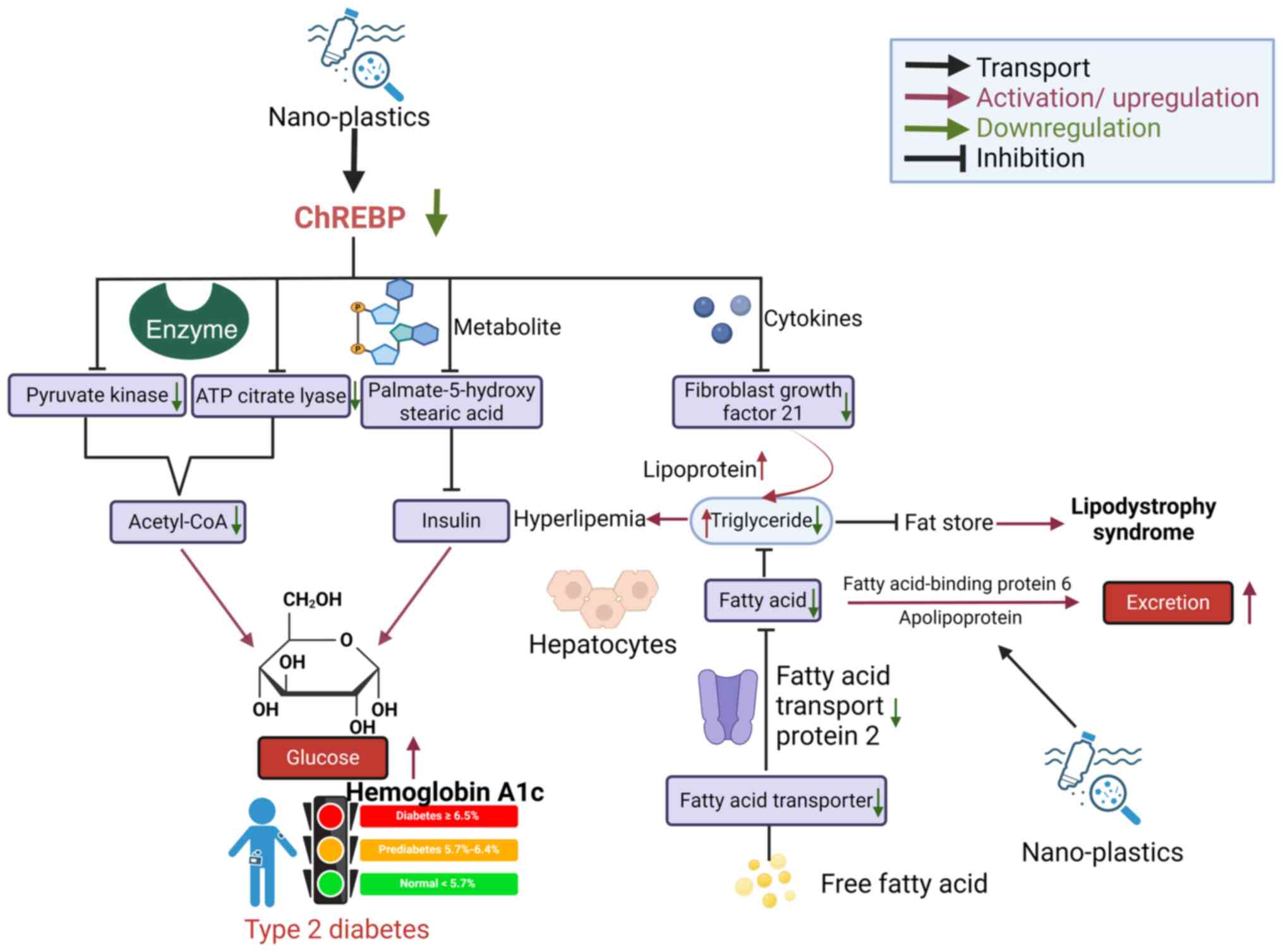

Effect of NPs on production of

intermediate metabolites for glycolipid metabolism

NPs affect glycolipid metabolism by influencing the

production of intermediate metabolites. Pyruvate is a key

intermediate metabolite in the glycolytic pathway and creates a

notable association between glucose and lipid metabolism (64). Its increased production may be due

to elevated levels of pyruvate kinase (PK) and phosphoenolpyruvate

carboxykinase (64,65), which may promote the conversion of

glucose to lipid metabolism and lead to increased production of

fatty acids. Elevated levels of glucose and cholesterol in the

liver may increase risk of type II diabetes, hyperlipidemia and

fatty liver disease (64). A study

revealed that biochemical levels of important factors and catalytic

enzymes (Aldh9a1a, Aldh2b, Ehhadh and Echs1) involved in regulation

of glucose metabolism in liver tissues are altered after the

ingestion of NPs (65). The

expression of carbohydrate regulatory element-binding protein

(ChREBP) (63), which prevents the

conversion of glucose to acetyl coenzyme A by inhibiting production

of PK and ATP-citrate lyase (ACL) in the liver cells of mice

following ingestion of NPs, is considerably reduced, resulting in a

marked decrease in glucose metabolism. By inhibiting production of

PK and ACL, ChREBP prevents conversion of glucose to acetyl

coenzyme A, leading to the accumulation of glycogen in the liver

and increasing the risk of type II diabetes (66). In addition, decrease in ChREBP

synthesis also leads to a decrease in the synthesis of

palmitic-5-hydroxystearic acid, which has been shown to increase

insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue (67) and insulin secretion through

activation of G protein-coupled receptor 40 (68); decrease in the expression of ChREBP

as a direct result of NPs indirectly inhibits insulin sensitivity

and secretion. Therefore, NPs indirectly inhibit insulin

sensitivity and secretion and hinder the glycolysis pathway leading

to glucose metabolism disorders (69). NPs can increase the activities of

lactate dehydrogenase and citrate synthase (CS), the key enzymes

participating in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis (69). This leads to glucose metabolism

disorder (Fig. 2), but the

specific mechanism of the influence of NPs on enzyme activities is

unclear (70).

In terms of lipid metabolism, NPs decrease

expression of ChREBP, leading to a decrease in fibroblast growth

factor 21 (FGF21) synthesis in hepatocytes, which inhibits the role

of FGF21 in decreasing plasma triglycerides by increasing

catabolism of lipoproteins in adipose tissue. Thus, plasma

triglycerides build up, leading to an increased risk of

hyperlipidemia in humans (71,72).

Free fatty acids from the blood enter hepatocytes to synthesize

fatty acids in liver tissues. However, a study revealed that

synthesis of fatty acid transporter (FAT) protein 2 and FAT was

reduced after NP treatment of hepatocytes (63), preventing transport of fatty acids

from the blood to the liver, indirectly impeding synthesis of fatty

acids in the liver. Another study revealed that the synthesis of

ApoE and fatty acid-binding protein 6 was decreased after treatment

of hepatocytes with NPs (73), and

the synthesis of fatty acids in the liver is indirectly impeded.

Therefore, the decreased levels of fatty acids in the liver leads

to insufficient synthesis of triglycerides, which indirectly

affects storage of fat. The lack of fat storage may lead to

lipodystrophy syndrome (73).

Lipodystrophy syndrome is a metabolic disorder that leads to

metabolic complications similar to those observed in obese

patients, such as those with insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus,

hepatic steatosis and dyslipidemia (74).

In summary, in glucose metabolism, NPs inhibit

synthesis of ChREBP, impede the conversion of glucose to

acetyl-coenzyme A and inhibit the sensitivity and secretion of

insulin. Taken together, these lead to the accumulation of glucose

causing disorders of glucose metabolism. In lipid metabolism, NPs

inhibit the production of fatty acids and simultaneously facilitate

the transport of fatty acids out of the cell, indirectly leading to

a decrease in triglyceride content and fat storage (Fig. 2).

NPs affect production of intermediate

metabolites for glycolipid metabolism at the transcription

level

Studies have revealed that NPs can affect key

rate-limiting enzymes involved in glucose metabolism, including

hexokinase 1 (HK1), PK and CS. In a study, zebrafish were given

polystyrene MPs and the liver tissue was extracted for

transcriptome analysis; transcript levels of PK were markedly

decreased in the experimental compared with those in the control

group, while the transcript levels of PK1 markedly increased in the

experimental group (65). HK1 is a

member of the hexokinase family that catalyzes the conversion of

glucose to fructose; increase of the HK1 transcript levels results

in an increase in the synthesis of HK1 protein, which increases

glucose conversion to fructose (74). Decreased levels of PK inhibit the

conversion of fructose to pyruvate, leading to the accumulation of

fructose; the accumulated fructose reaches the intestinal tract

through the blood circulation and accumulates in the intestine,

where it is used by the intestinal flora to produce acetate

(74). The acetate reaches the

liver through the portal vein and is converted into acetyl coenzyme

A, which is used as a substrate for lipogenesis, resulting in an

increase of adipogenesis (75). CS

is a key enzyme in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, converting

oxaloacetic to citric acid. Transcriptome analysis has revealed

that MPs lead to a decrease in the transcription of CS, leading to

a decrease in the synthesis of oleanic and α-ketoglutaric acid

(76), which affects the

tricarboxylic acid cycle and leads to disorders of glucose and

lipid metabolism.

Influencing fatty acid synthesis and β-oxidation at

the transcriptional level is another mechanism by which NPs affect

lipid metabolism. Fatty acid synthesis and β-oxidation are key

components of glycolipid metabolism (76). When studying the effects of NPs on

hepatic lipid metabolism, key enzymes involved in fatty acid

synthesis and β-oxidation, such as SLC27A, ACS and CPT1A, serve as

important biomarkers (77). The

transcript levels of the relevant genes are examined to investigate

the effects of NPs on glycolipid metabolism pathways and the

signaling pathways involved (78,79).

Studies have shown that NPs promote fatty acid synthesis by

promoting transcription of mRNAs for acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase

1, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1α and fatty acid

synthase (77). NPs inhibit fatty

acid β-oxidation by suppressing the transcription of mRNAs for

acetyl coenzyme A oxidase and cotinine palmitoyl transferase 1

oxidation of fatty acids (78).

PPAR-α and -γ are ligand-activated receptors in the nuclear hormone

receptor family that serve as transcriptional activator proteins to

regulate expression of oxidative enzymes in peroxisomes, which

contain a variety of oxidative enzymes involved in various types of

metabolism, including β-oxidation of fatty acids, bile acids and

cholesterol metabolism (80). NPs

affect the PPAR signaling pathway by increasing the transcript

levels of PPAR-α and -γ. Elevation of the transcript levels of

PPAR-α leads to an increase in the amount of oxidative enzymes in

peroxisomes, which promotes β-oxidation of fatty acids, bile acid

and cholesterol metabolism (77).

A marked increase in size and number of peroxisomes in the liver

can lead to hepatic hypertrophy, hyperplasia and hepatocellular

carcinoma (77). PPAR-γ is

involved in the differentiation and maturation of adipocytes

(81); increases of its

transcriptional level promotes the synthesis of fats, contributing

to disorders of lipid metabolism. Diacylglycerol acyltransferase

(DGAT) is a key enzyme in the synthesis of triglycerides and lipid

droplets in adipocytes; DDGAT serves an important role in the

regulation of lipid metabolism (82). NPs inhibit mRNA transcription of

DGAT, resulting in the reduction of the expression of DGAT,

inhibition of the formation of lipid droplets and fatty acids and

the reduction of lipid storage. DGAT2-deficient mice died soon

after birth due to the severe reduction in energy metabolism

substrates and impaired skin permeability barrier function

(83). Therefore, inhibition of

DGAT mRNA transcription by NPs not only affects lipid metabolism,

but also causes damage to the skin permeability barrier function,

which is harmful to human health.

In summary, after MPs and NPs enter the human body

by ingestion, NPs reach the liver through the circulatory system

and cause disorders in glucose and lipid metabolism of the liver

including enlargement, hyperplasia, type II diabetes,

hyperlipidemia and lipodystrophy syndrome and may contribute to

occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Discussion

As MPs and NPs are widely located in the biosphere,

their impact on human health is of concern. Studies have

demonstrated that humans are continuously exposed to MPs and NPs by

inhalation or ingestion (4–6).

When MPs and NPs enter the human body, larger particles are

eliminated in feces, while smaller particles are processed by

gastric juices and intestinal mucus, accumulating in the

gastrointestinal tract (84) where

they are absorbed into the cells (16). Current research suggests that a

small proportion of particles cross the lung and intestinal

barriers and accumulate in tissues and organs. Particles with

diameter <150 µm are able to travel from the intestinal lumen to

the lymphatic and circulatory system, accumulating in tissues

throughout the body, including the liver, kidney and brain,

producing various toxic effects (62). MPs and NPs induce oxidative stress

in cells by two methods: Direct stimulation of intracellular ROS

production and inhibition of antioxidant enzymes and GSH synthesis,

resulting in ROS metabolism (50).

The inflammatory response in the gastrointestinal tract is

primarily induced by direct stimulation of phagocytosis to secrete

proinflammatory cytokines and disruption of intestinal bacterial

flora, which leads to an increase in the number of conditionally

pathogenic bacteria (41).

Inflammation, oxidative stress and DNA damage caused by NPs

entering cells activate the apoptotic signaling pathway, leading to

cell death. At the biochemical level, NPs mainly affect the

production and metabolism of glucose, triglycerides and fatty

acids, while at the transcriptional level, NPs primarily affect

production of rate-limiting enzymes of glycolipid metabolism,

leading to disorders of glycolipid metabolism. The gastrointestinal

toxicity effects of MPs and NPs and effects on hepatic glucose

metabolism increase the risk of gastroenteritis, hyperglycemia,

diabetes mellitus, hepatic hypertrophy, hyperlipidemia and

lipodystrophy, posing a threat to human health (79).

Studies on toxic effects and mechanisms of MPs and

NPs on the gastrointestinal tract and liver are based on human

cells, rodents and aquatic species (43,59).

Although the aforementioned studies have provided evidence of the

possible toxic effects of MPs and NPs on the gastrointestinal tract

and liver in humans, there is lack of knowledge regarding the

absorption, metabolism and excretion of MPs and NPs in the human

body. Additionally, the ability of MPs and NPs to cross the human

tissue barrier is unclear; further studies are needed to

investigate the mechanisms by which MPs and NPs cross the

gastrointestinal barrier and the mechanisms underlying the toxic

effects caused by MPs and NPs. Studies have found that MPs and NPs

impair intestinal barrier function by decreasing intestinal mucus

secretion, inhibiting synthesis of tight junction proteins,

increasing intestinal permeability and causing disruption of

intestinal flora (38,41,47).

To the best of our knowledge, however, there is still a lack of

research on the specific mechanisms by which MPs and NPs impair the

gastrointestinal barrier.

In vitro studies investigating the toxic

effects of MPs and NPs on the gastrointestinal tract and liver use

concentrations of MPs and NPs that are higher than the actual

concentrations humans are exposed to in real life (15,20,30).

Therefore, there is a need to understand the toxic metabolism

kinetics of MPs and NPs within the context of the actual

concentrations to which humans are exposed. Furthermore, there are

differences in the immunological capacity and immune status between

individuals that should be considered when assessing toxicological

effects in humans.

An increasing number of studies have found that MPs

and NPs affect the immune system, as evidenced by the induction of

intestinal flora dysbiosis by MPs and NPs, leading to immune

imbalance and uptake of NPs by lymphocytes (40,57,85).

However, studies of toxic effects of MPs and NPs on immune cells

are limited, and there is lack of studies investigating the toxic

effects of MPs and NPs on the immune system as a whole (59). The gut microbiota, which is not

only an important component of immune and metabolic health but also

affects the central nervous system, has been shown to communicate

through several pathways of the ‘brain-gut axis,’ as identified

using animal models (44,63,86).

Therefore, the toxic effects and mechanisms of MPs and NPs on the

brain-gut axis following gut flora disruption should be further

investigated.

The gastrointestinal tract and liver are key organs

for absorption, metabolism and detoxification. The harmful effects

of MPs and NPs involve the intestinal-hepatic axis, causing

oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis and disorders of hepatic

glucose and lipid metabolism in the gastrointestinal tract,

resulting in gastroenteritis, hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia

(43). MPs and NPs also indirectly

affect the brain-gut axis through the intestinal flora. Therefore,

the toxic effects of MPs and NPs on the gastrointestinal tract and

liver and their mechanisms should be investigated further.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

LZ and YXH conceived the study. LZ and LDR performed

the literature review and data analysis. LZ, YFH and YXH

contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. LZ, LDR,

YFH and YXH wrote the manuscript and coordinated the revisions.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ragusa A, Svelato A, Santacroce C,

Catalano P, Notarstefano V, Carnevali O, Papa F, Rongioletti MCA,

Baiocco F, Draghi S, et al: Plasticenta: First evidence of

microplastics in human placenta. Environ Int. 146:1062742021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rochman CM, Hoh E, Hentschel BT and Kaye

S: Long-term field measurement of sorption of organic contaminants

to five types of plastic pellets: Implications for plastic marine

debris. Environ Sci Technol. 47:1646–1654. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang W, Ge J, Yu X and Li H: Environmental

fate and impacts of microplastics in soil ecosystems: Progress and

perspective. Sci Total Environ. 708:1348412020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Prata JC, da Costa JP, Lopes I, Duarte AC

and Rocha-Santos T: Environmental exposure to microplastics: An

overview on possible human health effects. Sci Total Environ.

702:1344552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pironti C, Ricciardi M, Motta O, Miele Y,

Proto A and Montano L: Microplastics in the environment: intake

through the food web, human exposure and toxicological effects.

Toxics. 9:2242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Thomas PJ, Perono G, Tommasi F, Pagano G,

Oral R, Burić P, Kovačić I, Toscanesi M, Trifuoggi M and Lyons DM:

Resolving the effects of environmental micro- and nanoplastics

exposure in biota: A knowledge gap analysis. Sci Total Environ.

780:1465342021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Amereh F, Amjadi N, Mohseni-Bandpei A,

Isazadeh S, Mehrabi Y, Eslami A, Naeiji Z and Rafiee M: Placental

plastics in young women from general population correlate with

reduced foetal growth in IUGR pregnancies. Environ Pollut.

314:1201742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Leslie HA, van Velzen MJM, Brandsma SH,

Vethaak AD, Garcia-Vallejo JJ and Lamoree MH: Discovery and

quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood.

Environ Int. 163:1071992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Schwabl P, Köppel S, Königshofer P,

Bucsics T, Trauner M, Reiberger T and Liebmann B: Detection of

various microplastics in human stool: A prospective case series.

Ann Intern Med. 171:453–457. 2019. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tong X, Li B, Li J, Li L, Zhang R, Du Y

and Zhang Y: Polyethylene microplastics cooperate with Helicobacter

pylori to promote gastric injury and inflammation in mice.

Chemosphere. 288((Pt 2)): 1325792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Luo T, Wang C, Pan Z, Jin C, Fu Z and Jin

Y: Maternal polystyrene microplastic exposure during gestation and

lactation altered metabolic homeostasis in the dams and their F1

and F2 offspring. Environ Sci Technol. 53:10978–10992. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang L, Wang Y, Xu M, Ma J, Zhang S, Liu

S, Wang K, Tian H and Cui J: Enhanced hepatic cytotoxicity of

chemically transformed polystyrene microplastics by simulated

gastric fluid. J Hazard Mater. 410:1245362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yee MS, Hii LW, Looi CK, Lim WM, Wong SF,

Kok YY, Tan BK, Wong CY and Leong CO: Impact of microplastics and

nanoplastics on human health. Nanomaterials (Basel). 11:4962021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hesler M, Aengenheister L, Ellinger B,

Drexel R, Straskraba S, Jost C, Wagner S, Meier F, von Briesen H,

Büchel C, et al: Multi-endpoint toxicological assessment of

polystyrene nano- and microparticles in different biological models

in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 61:1046102019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cortés C, Domenech J, Salazar M, Pastor S,

Marcos R and Hernández A: Nanoplastics as a potential environmental

health factor: Effects of polystyrene nanoparticles on human

intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells. Environ Sci Nano. 7:272–285.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Dong X, Liu X, Hou Q and Wang Z: From

natural environment to animal tissues: A review of

microplastics(nanoplastics) translocation and hazards studies. Sci

Total Environ. 855:1586862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Campanale C, Massarelli C, Savino I,

Locaputo V and Uricchio VF: A detailed review study on potential

effects of microplastics and additives of concern on human health.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17:12122020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Barboza LGA, Dick Vethaak A, Lavorante

BRBO, Lundebye AK and Guilhermino L: Marine microplastic debris: An

emerging issue for food security, food safety and human health. Mar

Pollut Bull. 133:336–348. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bouwmeester H, Hollman PC and Peters RJ:

Potential health impact of environmentally released micro- and

nanoplastics in the human food production chain: Experiences from

nanotoxicology. Environ Sci Technol. 49:8932–8947. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Domenech J, Hernández A, Rubio L, Marcos R

and Cortés C: Interactions of polystyrene nanoplastics with in

vitro models of the human intestinal barrier. Arch Toxicol.

94:2997–3012. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hussain N, Jaitley V and Florence AT:

Recent advances in the understanding of uptake of microparticulates

across the gastrointestinal lymphatics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev.

50:107–142. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Eldridge JH, Meulbroek JA, Staas JK, Tice

TR and Gilley RM: Vaccine-containing biodegradable microspheres

specifically enter the gut-associated lymphoid tissue following

oral administration and induce a disseminated mucosal immune

response. Adv Exp Med Biol. 251:191–202. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jani PU, McCarthy DE and Florence AT:

Nanosphere and microsphere uptake via Peyer's patches: Observation

of the rate of uptake in the rat after a single oral dose. Int J

Pharm. 86:239–246. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Volkheimer G: Hematogenous dissemination

of ingested polyvinyl chloride particles. Ann N Y Acad Sci.

246:164–171. 1975. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Banerjee A and Shelver WL: Micro- and

nanoplastic induced cellular toxicity in mammals: A review. Sci

Total Environ. 755((Pt 2)): 1425182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Varela JA, Bexiga MG, Åberg C, Simpson JC

and Dawson KA: Quantifying size-dependent interactions between

fluorescently labeled polystyrene nanoparticles and mammalian

cells. J Nanobiotechnology. 10:392012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nowak M, Brown TD, Graham A, Helgeson ME

and Mitragotri S: Size, shape, and flexibility influence

nanoparticle transport across brain endothelium under flow. Bioeng

Transl Med. 5:e101532020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Firdessa R, Oelschlaeger TA and Moll H:

Identification of multiple cellular uptake pathways of polystyrene

nanoparticles and factors affecting the uptake: Relevance for drug

delivery systems. Eur J Cell Biol. 93:323–337. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gratton SE, Ropp PA, Pohlhaus PD, Luft JC,

Madden VJ, Napier ME and DeSimone JM: The effect of particle design

on cellular internalization pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

105:11613–11618. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Carr KE, Smyth SH, McCullough MT, Morris

JF and Moyes SM: Morphological aspects of interactions between

microparticles and mammalian cells: Intestinal uptake and onward

movement. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 46:185–252. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Schmidt C, Lautenschlaeger C, Collnot EM,

Schumann M, Bojarski C, Schulzke JD, Lehr CM and Stallmach A: Nano-

and microscaled particles for drug targeting to inflamed intestinal

mucosa: A first in vivo study in human patients. J Control Release.

165:139–145. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li S and Malmstadt N: Deformation and

poration of lipid bilayer membranes by cationic nanoparticles. Soft

Matter. 9:4969–4976. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Xie W, You J, Zhi C and Li L: The toxicity

of ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) to vascular endothelial

cells. J Appl Toxicol. 41:713–723. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Gopinath PM, Saranya V, Vijayakumar S,

Mythili Meera M, Ruprekha S, Kunal R, Pranay A, Thomas J, Mukherjee

A and Chandrasekaran N: Assessment on interactive prospectives of

nanoplastics with plasma proteins and the toxicological impacts of

virgin, coronated and environmentally released-nanoplastics. Sci

Rep. 9:88602019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hollóczki O and Gehrke S: Nanoplastics can

change the secondary structure of proteins. Sci Rep. 9:160132019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Goodman KE, Hare JT, Khamis ZI, Hua T and

Sang QA: Exposure of human lung cells to polystyrene microplastics

significantly retards cell proliferation and triggers morphological

changes. Chem Res Toxicol. 34:1069–1081. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Xu M, Halimu G, Zhang Q, Song Y, Fu X, Li

Y, Li Y and Zhang H: Internalization and toxicity: A preliminary

study of effects of nanoplastic particles on human lung epithelial

cell. Sci Total Environ. 694:1337942019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hirt N and Body-Malapel M: Immunotoxicity

and intestinal effects of nano- and microplastics: A review of the

literature. Part Fibre Toxicol. 17:572020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Cheng W, Li X, Zhou Y, Yu H, Xie Y, Guo H,

Wang H, Li Y, Feng Y and Wang Y: Polystyrene microplastics induce

hepatotoxicity and disrupt lipid metabolism in the liver organoids.

Sci Total Environ. 806((Pt 1)): 1503282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li B, Ding Y, Cheng X, Sheng D, Xu Z, Rong

Q, Wu Y, Zhao H, Ji X and Zhang Y: Polyethylene microplastics

affect the distribution of gut microbiota and inflammation

development in mice. Chemosphere. 244:1254922020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu S, Li H, Wang J, Wu B and Guo X:

Polystyrene microplastics aggravate inflammatory damage in mice

with intestinal immune imbalance. Sci Total Environ.

833:1551982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Deng Y, Yan Z, Shen R, Wang M, Huang Y,

Ren H, Zhang Y and Lemos B: Microplastics release phthalate esters

and cause aggravated adverse effects in the mouse gut. Environ Int.

143:1059162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Shi C, Han X, Guo W, Wu Q, Yang X, Wang Y,

Tang G, Wang S, Wang Z, Liu Y, et al: Disturbed Gut-liver axis

indicating oral exposure to polystyrene microplastic potentially

increases the risk of insulin resistance. Environ Int.

164:1072732022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Jin Y, Lu L, Tu W, Luo T and Fu Z: Impacts

of polystyrene microplastic on the gut barrier, microbiota and

metabolism of mice. Sci Total Environ. 649:308–317. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Hwang J, Choi D, Han S, Choi J and Hong J:

An assessment of the toxicity of polypropylene microplastics in

human derived cells. Sci Total Environ. 684:657–669. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ding Y, Zhang R, Li B, Du Y, Li J, Tong X,

Wu Y, Ji X and Zhang Y: Tissue distribution of polystyrene

nanoplastics in mice and their entry, transport, and cytotoxicity

to GES-1 cells. Environ Pollut. 280:1169742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Domenech J, de Britto M, Velázquez A,

Pastor S, Hernández A, Marcos R and Cortés C: Long-term effects of

polystyrene nanoplastics in human intestinal caco-2 cells.

Biomolecules. 11:14422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Eleutherio ECA, Silva Magalhães RS, de

Araújo Brasil A, Monteiro Neto JR and de Holanda Paranhos L: SOD1,

more than just an antioxidant. Arch Biochem Biophys.

697:1087012021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Johnson P: Antioxidant enzyme expression

in health and disease: Effects of exercise and hypertension. Comp

Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 133:493–505. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Jakubczyk K, Dec K, Kałduńska J, Kawczuga

D, Kochman J and Janda K: Reactive oxygen species-sources,

functions, oxidative damage. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 48:124–127.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wang X, Zheng H, Zhao J, Luo X, Wang Z and

Xing B: Photodegradation elevated the toxicity of polystyrene

microplastics to grouper (Epinephelus moara) through disrupting

hepatic lipid homeostasis. Environ Sci Technol. 54:6202–6212. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

DeLoid GM, Cao X, Bitounis D, Singh D,

Llopis PM, Buckley B and Demokritou P: Toxicity, uptake, and

nuclear translocation of ingested micro-nanoplastics in an in vitro

model of the small intestinal epithelium. Food Chem Toxicol.

158:1126092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

He Y, Li Z, Xu T, Luo D, Chi Q, Zhang Y

and Li S: Polystyrene nanoplastics deteriorate LPS-modulated

duodenal permeability and inflammation in mice via ROS

drived-NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway. Chemosphere. 307((Pt 1)): 1356622022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Deng Y, Zhang Y, Lemos B and Ren H: Tissue

accumulation of microplastics in mice and biomarker responses

suggest widespread health risks of exposure. Sci Rep. 7:466872017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Rubio L, Marcos R and Hernández A:

Potential adverse health effects of ingested micro- and

nanoplastics on humans. Lessons learned from in vivo and in vitro

mammalian models. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 23:51–68.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Powell JJ, Thoree V and Pele LC: Dietary

microparticles and their impact on tolerance and immune

responsiveness of the gastrointestinal tract. Br J Nutr. 98 (Suppl

1):S59–S63. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Huang D, Zhang Y, Long J, Yang X, Bao L,

Yang Z, Wu B, Si R, Zhao W, Peng C, et al: Polystyrene microplastic

exposure induces insulin resistance in mice via dysbacteriosis and

pro-inflammation. Sci Total Environ. 838((Pt 1)): 1559372022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Forte M, Iachetta G, Tussellino M,

Carotenuto R, Prisco M, De Falco M, Laforgia V and Valiante S:

Polystyrene nanoparticles internalization in human gastric

adenocarcinoma cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 31:126–136. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM and

Aggarwal BB: Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: How are

they linked? Free Radic Biol Med. 49:1603–1616. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Yan X, Zhang Y, Lu Y, He L, Qu J, Zhou C,

Hong P, Sun S, Zhao H, Liang Y, et al: The complex toxicity of

tetracycline with polystyrene spheres on gastric cancer cells. Int

J Environ Res Public Health. 17:28082020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Chen Z, Wang C, Yu N, Si L, Zhu L, Zeng A,

Liu Z and Wang X: INF2 regulates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis

in epidermal HaCaT cells by modulating the HIF1 signaling pathway.

Biomed Pharmacother. 111:151–161. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Vethaak AD and Legler J: Microplastics and

human health. Science. 371:672–674. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Lu L, Wan Z, Luo T, Fu Z and Jin Y:

Polystyrene microplastics induce gut microbiota dysbiosis and

hepatic lipid metabolism disorder in mice. Sci Total Environ.

631-632:449–458. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Wan Z, Wang C, Zhou J, Shen M, Wang X, Fu

Z and Jin Y: Effects of polystyrene microplastics on the

composition of the microbiome and metabolism in larval zebrafish.

Chemosphere. 217:646–658. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhao Y, Bao Z, Wan Z, Fu Z and Jin Y:

Polystyrene microplastic exposure disturbs hepatic glycolipid

metabolism at the physiological, biochemical, and transcriptomic

levels in adult zebrafish. Sci Total Environ. 710:1362792020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Shi L and Tu BP: Acetyl-CoA and the

regulation of metabolism: mechanisms and consequences. Curr Opin

Cell Biol. 33:125–131. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Zhou P, Santoro A, Peroni OD, Nelson AT,

Saghatelian A, Siegel D and Kahn BB: PAHSAs enhance hepatic and

systemic insulin sensitivity through direct and indirect

mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 129:4138–4150. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Syed I, Lee J, Moraes-Vieira PM, Donaldson

CJ, Sontheimer A, Aryal P, Wellenstein K, Kolar MJ, Nelson AT,

Siegel D, et al: Palmitic acid hydroxystearic acids activate GPR40,

which is involved in their beneficial effects on glucose

homeostasis. Cell Metab. 27:419–427.e4. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Vijayakumar A, Aryal P, Wen J, Syed I,

Vazirani RP, Moraes-Vieira PM, Camporez JP, Gallop MR, Perry RJ,

Peroni OD, et al: Absence of carbohydrate response element binding

protein in adipocytes causes systemic insulin resistance and

impairs glucose transport. Cell Rep. 21:1021–1035. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wen B, Zhang N, Jin SR, Chen ZZ, Gao JZ,

Liu Y, Liu HP and Xu Z: Microplastics have a more profound impact

than elevated temperatures on the predatory performance, digestion

and energy metabolism of an Amazonian cichlid. Aquat Toxicol.

195:67–76. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Schlein C, Talukdar S, Heine M, Fischer

AW, Krott LM, Nilsson SK, Brenner MB, Heeren J and Scheja L: FGF21

lowers plasma triglycerides by accelerating lipoprotein catabolism

in white and brown adipose tissues. Cell Metab. 23:441–453. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Iizuka K, Takeda J and Horikawa Y: Glucose

induces FGF21 mRNA expression through ChREBP activation in rat

hepatocytes. FEBS Lett. 583:2882–2886. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Bi Y, Chang Y, Liu Q, Mao Y, Zhai K, Zhou

Y, Jiao R and Ji G: ERp44/CG9911 promotes fat storage in Drosophila

adipocytes by regulating ER Ca(2+) homeostasis. Aging (Albany NY).

13:15013–15031. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Simha V and Garg A: Lipodystrophy: Lessons

in lipid and energy metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 17:162–169.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Iizuka K, Takao K and Yabe D:

ChREBP-mediated regulation of lipid metabolism: Involvement of the

gut microbiota, liver, and adipose tissue. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 11:5871892020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Nunes-Nesi A, Araújo WL, Obata T and

Fernie AR: Regulation of the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid

cycle. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 16:335–343. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Bougarne N, Weyers B, Desmet SJ, Deckers

J, Ray DW, Staels B and De Bosscher K: Molecular actions of

PPARalpha in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Endocr Rev.

39:760–802. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Wang Q, Wu Y, Zhang W, Shen T, Li H, Wu J,

Zhang L, Qin L, Chen R, Gu W, et al: Lipidomics and transcriptomics

insight into impacts of microplastics exposure on hepatic lipid

metabolism in mice. Chemosphere. 308((Pt 3)): 1365912022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Fan X, Wei X, Hu H, Zhang B, Yang D, Du H,

Zhu R, Sun X, Oh Y and Gu N: Effects of oral administration of

polystyrene nanoplastics on plasma glucose metabolism in mice.

Chemosphere. 288((Pt 3)): 1326072022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Islinger M, Cardoso MJ and Schrader M: Be

different-the diversity of peroxisomes in the animal kingdom.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1803:881–897. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Marion-Letellier R, Savoye G and Ghosh S:

Fatty acids, eicosanoids and PPAR gamma. Eur J Pharmacol.

785:44–49. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Bhatt-Wessel B, Jordan TW, Miller JH and

Peng L: Role of DGAT enzymes in triacylglycerol metabolism. Arch

Biochem Biophys. 655:1–11. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Stone SJ, Myers HM, Watkins SM, Brown BE,

Feingold KR, Elias PM and Farese RV Jr: Lipopenia and skin barrier

abnormalities in DGAT2-deficient mice. J Biol Chem.

279:11767–11776. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Stock V, Fahrenson C, Thuenemann A, Dönmez

MH, Voss L, Böhmert L, Braeuning A, Lampen A and Sieg H: Impact of

artificial digestion on the sizes and shapes of microplastic

particles. Food Chem Toxicol. 135:1110102020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Zhao L, Shi W, Hu F, Song X, Cheng Z and

Zhou J: Prolonged oral ingestion of microplastics induced

inflammation in the liver tissues of C57BL/6J mice through

polarization of macrophages and increased infiltration of natural

killer cells. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 227:1128822021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Qiao J, Chen R, Wang M, Bai R, Cui X, Liu

Y, Wu C and Chen C: Perturbation of gut microbiota plays an

important role in micro/nanoplastics-induced gut barrier

dysfunction. Nanoscale. 13:8806–8816. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|