Introduction

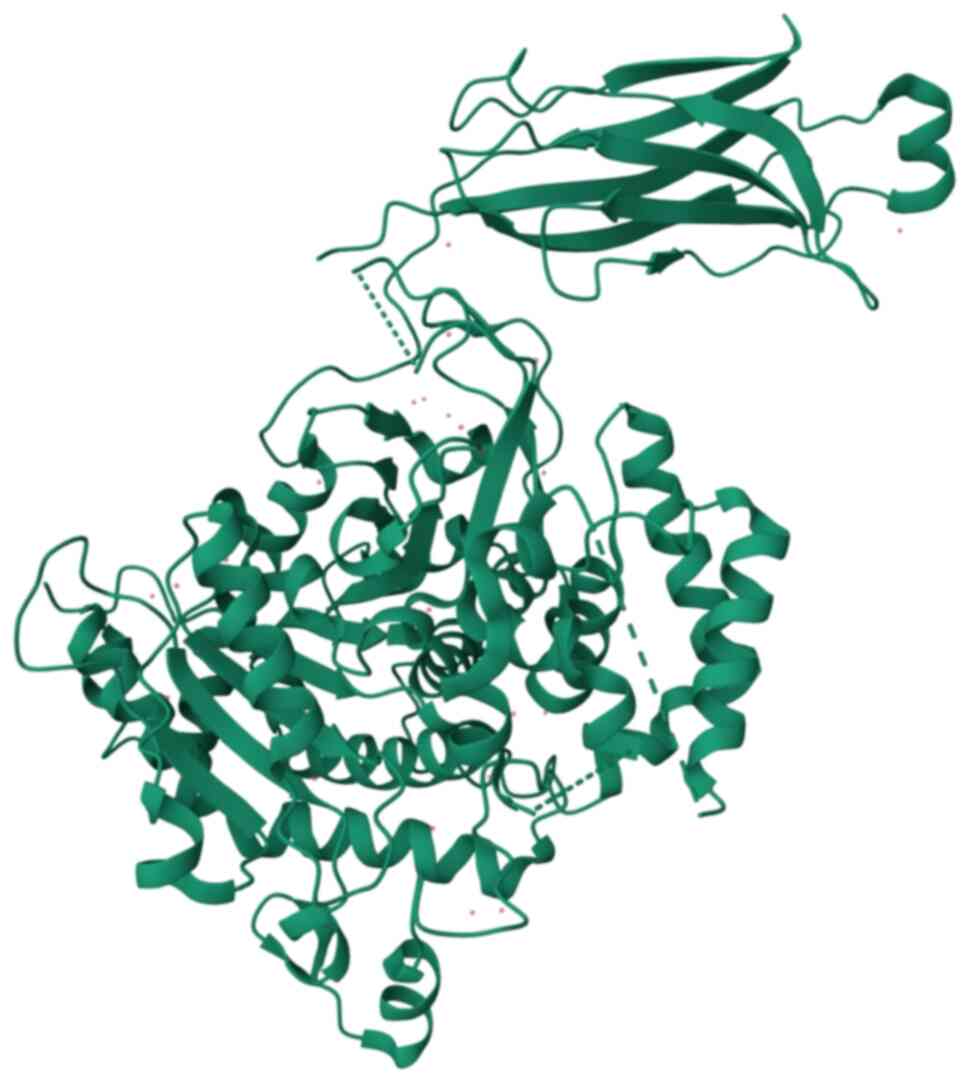

Cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2; Fig. 1) belongs to the lipolytic enzyme

family and hydrolyzes the ester bond at the sn-2 position of

phospholipids, generating free fatty acids and lysophospholipids.

Members of the PLA2 family are classified into six subfamilies

based on their location in the body, substrate specificity and

physiological functions: Secretory PLA2s (sPLA2s), cPLA2s,

Ca2+-independent PLA2s (iPLA2s), platelet-activating

factor acetylhydrolase PLA2s (PAF-AH PLA2s), lysosomal PLA2s

(LPLA2s) and adipose tissue-specific PLA2s (AdPLA2s). Among these,

cPLA2s play a crucial role in inflammatory diseases, cerebral

ischemia-reperfusion injury, hypertension and autoimmune diseases

(1–4).

cPLA2, a member of the PLA2 family, is a

single-subunit protein composed of 749 amino acids with two

functional domains: the Ca2+-dependent lipid-binding

(CaLB) domain, also known as the C2 domain and the catalytic active

region (CAT), connected by flexible hinges. cPLA2 primarily acts on

the phospholipid bilayer of cell membranes to catalyze the release

of free arachidonic acid (AA) (5).

cPLA2 is activated through two primary pathways: The

Ca2+-dependent pathway, when intracellular

Ca2+ levels rise, Ca2+ binds to the C2 domain

of cPLA2, facilitating its translocation from the cytoplasm to the

membrane's phospholipid matrix; the phosphorylation pathway, when

phosphorylation of amino acid residues in the hinge region between

the C2 domain and the catalytic domain enhances the binding

affinity and catalytic efficiency of cPLA2. This phosphorylation

induces conformational changes, bringing the catalytic domain

closer to the substrate. Ultimately, cPLA2 on the phospholipid

membrane catalyzes phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis, promoting AA

release (6,7). AA, an essential fatty acid, can be

metabolized into various bioactive substances, including

prostaglandins, platelet-activating factors and leukotrienes, which

regulate pathophysiological processes such as inflammation, cell

proliferation, apoptosis and platelet aggregation (8,9).

cPLA2 has been shown to participate in essential cellular

processes, including phospholipid metabolism, signal transduction

and membrane remodeling under physiological conditions (1,10,11).

However, increased cPLA2 activity and excessive AA release, along

with pro-inflammatory mediators, can compromise lysosomal membrane

integrity, exacerbating inflammation and oxidative stress under

pathological conditions (12).

Numerous studies have confirmed the involvement of cPLA2 in the

pathogenesis of various diseases. However, systematic summaries of

its role in cardiovascular diseases and underlying mechanisms

remain limited. Existing evidence indicates that cPLA2 plays a

pivotal role in the development of cardiovascular conditions,

including atherosclerosis, myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury

and hypertension (3,4,13)

(Table I). This review highlighted

the functional significance and potential mechanisms of cPLA2 in

cardiovascular diseases, offering novel insights into their

diagnosis and treatment.

| Table I.Roles and mechanisms of cPLA2 in

various cardiovascular diseases. |

Table I.

Roles and mechanisms of cPLA2 in

various cardiovascular diseases.

| Cardiovascular

diseases | cPLA2-related

pathogenic mechanisms | (Refs.) |

|---|

|

Atherosclerosis | Inflammatory

responses and oxidative stress lead to increased vascular

permeability, while the proliferation and migration of smooth

muscle cells contribute to plaque formation and vascular

remodeling. Excessive cell apoptosis results in endothelial cell

damage, accompanied by a blockade of autophagy flux, which causes

the accumulation of harmful substances and damaged organelles. | (13,28,29,32–35,56–60) |

| Coronary artery

disease | Inflammatory

responses provoke plaque instability and rupture, coupled with

platelet activation that causes platelet aggregation and thrombus

formation. | (28,60) |

| Myocardial

infarction | Inflammatory

responses and oxidative stress inflict damage on myocardial cells.

This is exacerbated by excessive cell apoptosis during reperfusion

injury and platelet activation, which together promote plaque and

thrombus formation. The process is further complicated by a

blockade of autophagy flux, leading to the accumulation of harmful

substances and damaged organelles. | (28,29,32–35,56–60) |

| Heart failure | The damage to

myocardial cells from inflammatory responses and oxidative stress

necessitates myocardial remodeling, involving cell apoptosis,

myocardial fibrosis and hypertrophy. This scenario is compounded by

the blockade of autophagy flux, resulting in the accumulation of

harmful substances and damaged organelles. | (32–35,56–60) |

| Hypertension | Inflammatory

responses and oxidative stress cause endothelial dysfunction

through inflammatory mediators, with subsequent vasoconstriction

regulated by sodium and calcium channels. This leads to

arteriosclerosis, which narrows blood vessels and is regulated

further by the renin-angiotensin system. | (13,67,74) |

| Cardiac valve

disease | Inflammatory

responses and oxidative stress lead to the destruction and

proliferation of valve tissue. This promotes valve cell

proliferation and migration, resulting in the thickening,

calcification and fibrosis of the valves. | (1,32–34,75) |

cPLA2 exacerbates inflammation

cPLA2 promotes the production and

release of inflammatory mediators

Tissue damage and oxidative stress can activate

cPLA2, which hydrolyzes the sn-2 site of membrane phospholipids to

produce metabolites, primarily AA and lysophospholipids. These

metabolites, in turn, generate downstream molecules such as

leukotrienes, prostaglandins, lipoxin A, thromboxane, sphingomyelin

and lysophosphatidic acid via cyclooxygenase (COX) and

lysophospholipase activity. These molecules trigger inflammatory

responses and oxidative stress, resulting in a robust inflammatory

cascade (14).

cPLA2 activates the inflammatory

signal conduction pathway

Key signaling pathways such as NF-κB and MAPKs play

critical roles in cell signal transmission, regulating processes

such as inflammation, immune responses, cell proliferation and

apoptosis. Studies have confirmed that cPLA2 activates these

inflammatory signaling pathways (1,15–18)

(Fig. 2).

NF-κB signaling pathway

NF-κB is a classical transcription factor that

regulates the expression of multiple genes by translocating from

the cytoplasm to the nucleus. It serves as a key regulator of

inflammatory responses, influencing both the progression and

resolution of inflammation. AA released by activated cPLA2 acts as

a second messenger, participating in downstream signaling

activation. AA is catalyzed by COX into prostaglandin H2 (PGH2),

which is subsequently converted into prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2

activates G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) on cell membranes,

triggering downstream signaling events such as the phosphorylation

and degradation of IκB (inhibitor of NF-κB). The degradation of IκB

releases active NF-κB, promoting its nuclear translocation and

binding to specific DNA sequences to initiate the transcription of

downstream genes. Excessive activation of cPLA2 can prolong NF-κB

activity, leading to sustained inflammatory responses and tissue

damage (15–17).

MAPKs signaling pathway

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) represent

a highly conserved cell signal transduction pathway that conveys

extracellular and intracellular signals to regulatory networks

through phosphorylation of key protein targets. The primary

components include ERK1/2, JNK and p38 MAPK (18). The MAPKs pathway can be activated

by various exogenous stimuli, such as growth factors, stress and

inflammatory factors, or endogenous stimuli, such as cellular

stress and DNA damage. Stimulation leads to the activation of

receptors, such as receptor tyrosine kinases and GPCRs, which

subsequently activate MAP3K through a series of downstream kinase

cascades. MAP3K phosphorylates MAP2K, which, in turn, activates

MAPK. This process triggers the activation of nuclear transcription

factors, ultimately regulating cellular physiological functions

(19). cPLA2 activates the MAPKs

signaling pathway through several mechanisms. Diacylglycerol,

generated by cPLA2-catalyzed phosphatidylinositol 2 (PIP2),

directly activates protein kinase C, which then stimulates the

MAPKs pathway (20). Additionally,

AA, a product of cPLA2 catalysis, plays a crucial role in the MAPKs

network. AA activates ERK, JNK and p38 MAPK, influencing processes

such as cell proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation. Among

these, p38 MAPK primarily mediates inflammatory responses and

cellular stress (18,21). In summary, cPLA2 serves as a key

upstream molecule in the activation of MAPKs signaling

pathways.

The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway

cPLA2, as a phosphatidylinositol-specific

phosphoesterase, activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway through

multiple mechanisms. It promotes this pathway by inducing the

production and release of growth factors. For instance, cPLA2

facilitates the secretion of TNF-α, which activates the PI3K/Akt

pathway (21). Moreover, cPLA2

enhances PI3K activity by regulating phosphatidylinositol content

in cell membranes, thereby increasing the affinity of PI3K

(22–24). Additionally, cPLA2 directly

activates Akt by promoting its phosphorylation and enhancing its

activity, which further drives the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway

(25).

cPLA2 participates in platelet

activation

A number of studies have demonstrated that cPLA2

plays a pivotal role in platelet activation. Platelet activation,

typically induced by external stimuli such as cytokines or vascular

damage, triggers intracellular signaling pathways that activate

cPLA2, leading to the release of AA. In platelets, AA is primarily

metabolized by COX-1 into PGH2, which is subsequently converted

into thromboxane A2 (TXA2) (26).

TXA2 promotes platelet activation and vasoconstriction (27). Upon activation, platelets release

bioactive substances such as platelet factor 4, platelet-derived

growth factor and ADP. These substances stimulate neighboring

platelets, enhancing adhesion and aggregation. Additionally,

activated platelets expose receptors, including GPIIb/IIIa and

GPIb/IX, on the endothelial surface. These receptors bind to

molecules such as fibronectin and von Willebrand factors, exposed

during vascular injury, further facilitating platelet aggregation

and the formation of platelet thrombi (28,29).

PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways are the two major signaling pathways

involved in platelet activation and aggregation. The PI3K/Akt

pathway is activated by various platelet agonists, including

thrombin, collagen and ADP, promoting platelet activation, granule

release and integrin activation. Similarly, the MAPK pathway is

activated by platelet agonists and regulates genes involved in

platelet functions, such as integrin and TXA production, thereby

enhancing platelet activation and aggregation (30,31).

In summary, cPLA2 is a critical regulator of platelet activation,

functioning through its involvement in the PI3K/Akt and MAPK

signaling pathways.

cPLA2 regulates myocardial cell

apoptosis

In the study of cell death, several mechanisms have

been recognized, including apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis and

ferroptosis. These mechanisms play critical roles in both

physiological and pathological cellular processes (32). cPLA2 plays a pivotal regulatory

role in cell death by catalyzing the hydrolysis of cell membrane

phospholipids to generate arachidonic acid and its metabolic

products (33). In necroptosis,

cPLA2 facilitates membrane remodeling and the release of necrotic

signals by regulating lipid metabolism and altering cell membrane

structure (34). In pyroptosis,

cPLA2 activates the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such

as IL-1β and IL-18, by releasing AA, which further promotes

inflammasome formation and triggers the pyroptotic response

(35). Additionally, during

ferroptosis, cPLA2 modulates membrane lipid peroxidation,

influencing oxidative damage to membrane lipids and the metabolism

of intracellular iron, thereby indirectly regulating ferroptosis

(36). The present review focused

on the critical role of cPLA2 in apoptosis, specifically its

regulation of the multiple signaling pathways involved in this

process.

Apoptosis is the most well-studied and classical

form of programmed cell death, crucial for maintaining normal

tissue structure and function. Excessive apoptosis of myocardial

cells results in significant cell loss, leading to myocardial

tissue depletion and impaired blood supply to the affected area

(37,38). This process triggers cardiac

fibrosis, where healthy myocardium is replaced by fibrous

connective tissue. Fibrosis renders the heart stiff, reduces its

elasticity and causes ventricular dilation. These changes

exacerbate cardiac remodeling, further impairing cardiac function

and leading to alterations in the overall structure of the heart

(39). Excessive apoptosis has

been implicated in myocardial ischemia, ischemia/reperfusion

injury, post-ischemic cardiac remodeling and the progression of

cardiovascular conditions such as coronary atherosclerosis,

myocardial infarction, hypertension and heart failure (40–44).

The following paragraphs elaborate on these processes (Fig. 2).

MAPKs signaling

cPLA2 and MAPK signaling pathways are closely linked

in the regulation of cell apoptosis. cPLA2 participates in the

metabolism of PIP2 on the cell membrane, converting it into

phosphatidylinositol triphosphate (PIP3) (2). PIP3 plays a crucial role in the

apoptotic process. cPLA2 activates PI3K through PIP3, which

subsequently activates MAPKKK, further stimulating the MAPK

signaling pathway (41). The MAPK

signaling pathway promotes apoptosis in various cell types,

including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, macrophages and tumor

cells, through different subtypes (such as JNK, p38 MAPK and ERK).

Activated JNK and p38 MAPK enhance the expression of

apoptosis-related transcription factors (such as p53) and increase

pro-apoptotic genes (such as Bax), while simultaneously

downregulating anti-apoptotic factors such as Bcl-2) (42,45).

In cardiomyocyte apoptosis, distinct MAPK members may have varying

roles (46). JNK activation

regulates cell apoptosis by either stimulating apoptotic factor

expression or inhibiting anti-apoptotic mechanisms. For instance,

JNK activates the transcription factor c-Jun, promoting the

expression of apoptosis-related genes, including apoptotic proteins

and mitochondrial regulatory factors, ultimately leading to cell

apoptosis in cardiomyocytes (47).

However, JNK activation may act as an anti-apoptotic factor in

cardiomyocytes derived from embryonic stem cells (48). Under pathological conditions such

as ischemia-reperfusion, inflammation and oxidative stress, p38

activation increases mitochondrial membrane permeability and

caspase enzyme activation, thereby promoting myocardial cell

apoptosis (49). ERK, through a

series of cascade reactions, plays a protective role in myocardial

cell apoptosis. ERK activation inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis by

upregulating the Bcl-2/Bax ratio through downregulation of Bax

expression, thereby maintaining mitochondrial stability (50). In summary, cPLA2 regulates

myocardial cell apoptosis by activating different members of the

MAPK signaling pathway.

PI3K/Akt signaling

The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway plays a crucial role

in regulating cell survival and apoptosis, primarily through its

control of anti-apoptotic mechanisms. Dysregulation of this pathway

is closely associated with the onset and progression of various

diseases, particularly cancer, neurodegenerative disorders and

cardiovascular diseases (51,52).

Akt is the primary effector kinase, regulating cell survival and

apoptosis by phosphorylating a series of downstream target

proteins. Akt reduces the pro-apoptotic effects of factors such as

Bad and Bax by phosphorylating and inhibiting them. It also

phosphorylates and activates anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2

and Bcl-xL, thereby enhancing cell survival (53). The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is

essential for the normal physiological functions of cardiomyocytes

and is closely related to cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Dysregulation of

this pathway can lead to cardiomyocyte apoptosis, contributing to

cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction and heart

failure (52). Activation of the

PI3K/Akt pathway promotes myocardial cell survival and inhibits

apoptosis (49). The PI3K/Akt

pathway regulates the release of AA and associated apoptosis

processes by inhibiting cPLA2 activity. Activated Akt directly

phosphorylates and inhibits cPLA2, reducing AA production (43). Additionally, Akt can regulate cPLA2

activity by preventing its translocation to the cell membrane, a

critical step in AA release. Akt signaling disrupts this process,

thereby decreasing AA production. However, under certain

pathological conditions, such as myocardial ischemia, injury, or

hypertrophy, the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is inhibited. This

inhibition weakens the effect of Akt on cPLA2, potentially leading

to cPLA2 activation, increased AA release and enhanced cell

apoptosis (54).

NF-κB signaling

As aforementioned, cPLA2 activates the NF-κB

signaling pathway by producing AA and its metabolites. This pathway

promotes cell apoptosis by regulating the expression of apoptotic

factors. NF-κB induces FasL expression, initiating apoptotic

signaling and promoting cell apoptosis. It may also increase the

production of TNF-α, which activates downstream apoptotic signals,

including Caspase-8, to initiate apoptosis (44). Additionally, NF-κB accelerates cell

apoptosis by regulating p53, further exacerbating cardiac damage

(55). These mechanisms play a

significant role in various cardiovascular diseases, including

heart failure and coronary artery disease (56). For example, NF-κB mediates

atherosclerosis through several key mechanisms: First, it promotes

endothelial cells to express pro-inflammatory molecules, recruiting

and activating inflammatory cells to enhance local inflammation.

Second, NF-κB affects the proliferation and migration of smooth

muscle cells, contributing to plaque formation. It also increases

oxidative stress, leads to endothelial injury and promotes the

formation of foam cells through the accumulation of cholesterol and

lipids. These processes collectively promote the development of

atherosclerosis (13,56).

cPLA2 participates in the autophagy

flux

Autophagy is a process of cellular self-degradation

that maintains cellular homeostasis by degrading and recycling

harmful or aging components, allowing cells to adapt to

environmental changes (57). This

process involves three main stages: Activation, transportation and

degradation. Specifically, it includes the formation of

phagophores, the development of autophagosomes, the fusion of

autophagosomes and lysosomes to form autolysosomes and the

subsequent degradation of substrates within them (58). This entire process is referred to

as autophagic flux. Studies have shown that autophagy plays a

crucial role in various cardiovascular diseases. The heart is a

highly metabolically active organ with significant demands for

oxygen and energy. Under conditions such as ischemia, reperfusion

injury, or other pathological states, autophagy can be activated to

meet energy needs, reduce oxidative stress, inhibit cell apoptosis

and maintain cellular homeostasis, thereby protecting the heart

from damage (59,60). In heart diseases such as myocardial

infarction and heart failure, autophagic flux is often inhibited or

impaired. This abnormal autophagic activity leads to the

accumulation of harmful substances and damaged organelles within

myocardial cells, further exacerbating cell damage (61,62).

Additionally, studies using acute hemodynamic stress models have

shown that excessive autophagy can result in increased myocardial

cell hypertrophy, impaired cardiac performance and the activation

of cardiac stromal cells (such as fibroblasts), promoting fibrosis.

These mechanisms suggest that excessive autophagy can have

pathological consequences, potentially contributing to cardiac

hypertrophy and heart failure (63,64).

Furthermore, autophagic flux dysfunction can reduce endothelial

cell tolerance to oxidative stress and inflammatory responses,

leading to the accumulation of oxidized LDL (low-density

lipoprotein) and promoting the formation and progression of

atherosclerosis. Excessive autophagy may also increase cell

apoptosis within plaques, compromising their structural stability

and making them more prone to rupture, thereby triggering

cardiovascular events (65).

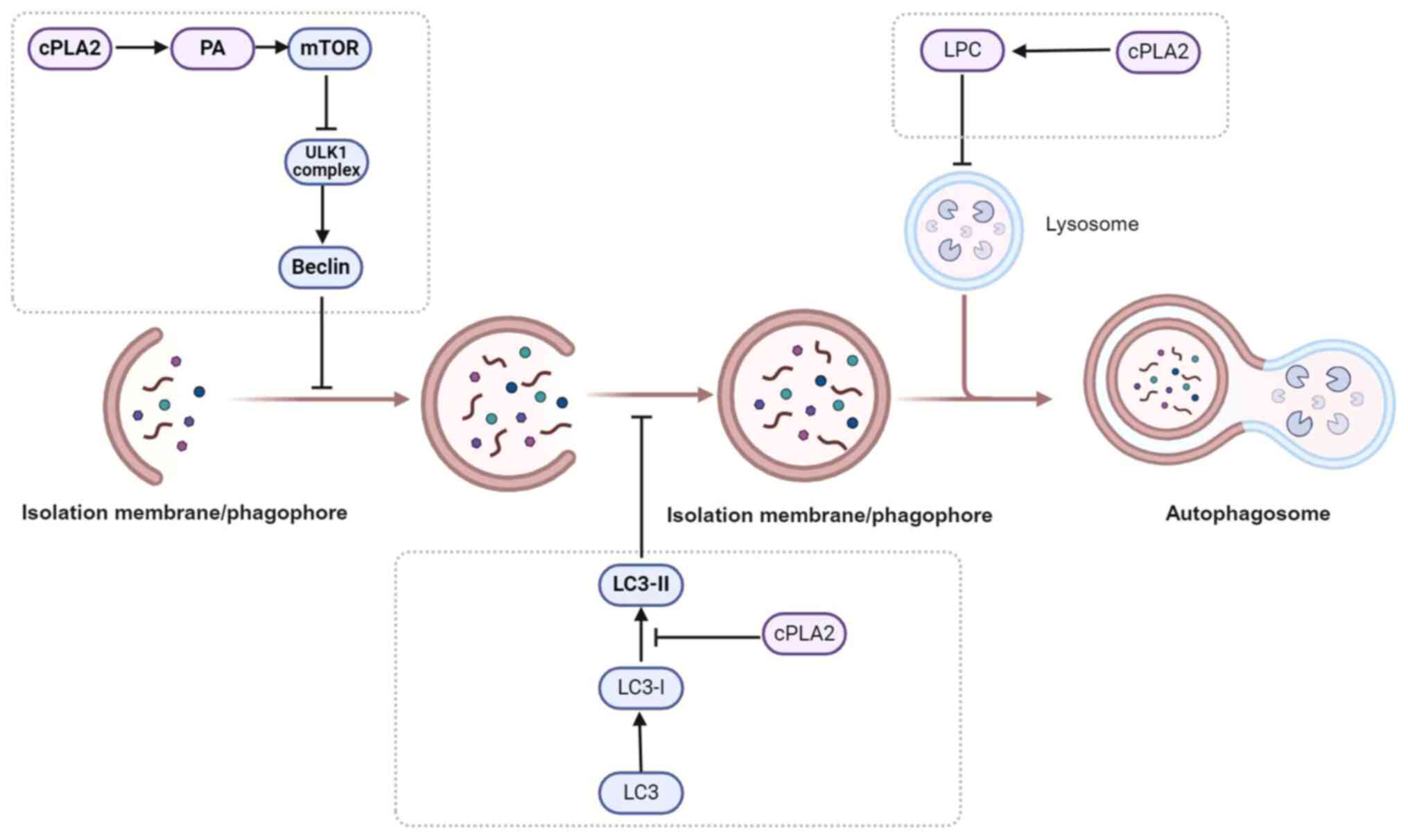

Studies have demonstrated that cPLA2 can regulate autophagic flux

through multiple pathways, contributing to various cardiovascular

diseases (49,66–75)

(Fig. 3).

cPLA2 inhibits the expression and

activity of autophagy-related proteins

In the early stages, when cells are exposed to

stress, nutrient deprivation and insufficient oxygen supply,

autophagy is activated (66).

These signals include the inhibition of mTOR complex 1 (C1),

activation of AMPK and an increase in intracellular calcium ion

concentration (67,68). The Unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1)

complex, which consists of proteins such as ULK1, focal adhesion

kinase family interacting protein of 200 kDa, autophagy-related 13,

autophagy-related 101, as well as the Beclin-1-VPS34 complex

(including Beclin-1, VPS34 and other auxiliary proteins), are

activated (46,69). These complexes interact to regulate

downstream autophagic processes. cPLA2 hydrolyzes

phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine to produce free

fatty acids, which promote the accumulation of intracellular

phosphatidic acid (PA). The accumulation of PA can activate mTORC1,

which inhibits the activity of the ULK1 complex and reduces the

formation of the Beclin-1-VPS34 complex, ultimately inhibiting

autophagy. Additionally, cPLA2 can reduce the expression of

Beclin-1 by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, further

suppressing autophagy (67–71).

cPLA2 reduces the formation of

autophagosome

After the initiation phase, autophagic vesicles

begin to form. These vesicles consist of a double membrane that

engulfs cellular components to be degraded. This process involves

multiple autophagy-related proteins, such as ATG9, ATG16L1 and the

ATG5-ATG12 complex (66,71). These proteins promote the formation

and expansion of autophagic vesicles through interactions and

phosphorylation. The vesicles close in a single step to form

autophagosomes. This process involves the lipidation of LC3,

wherein LC3-I is converted to LC3-II, which binds to the inner

membrane of the autophagic vesicle, promoting the formation and

closure of the autophagosome. The activation of cPLA2 can influence

the composition of membrane phospholipids, thereby affecting the

lipidation of LC3 proteins and their binding to the autophagosome

membrane. A study showed that inhibiting cPLA2 can promote the

accumulation of LC3-II (the phosphorylated form of LC3), thereby

increasing autophagosome formation (49).

cPLA2 blocks autophagy by destroying

the integrity of lysosomal membranes

After the formation of the autophagosome, it fuses

with lysosomes to form autophagic lysosomes (autolysosomes). The

components and organelles within the autophagosome are degraded by

hydrolytic enzymes in the autolysosome, facilitating the recovery

and reuse of intracellular components to meet the energy needs of

the cell and synthesize new biomolecules (57). cPLA2 is primarily responsible for

the sn-2 hydrolysis of membrane phospholipids on the cell membrane,

generating inflammatory mediators such as lysophospholipids and AA.

Lysophospholipids are a class of phosphatidylinositol metabolites

and important cell signaling molecules, including

lysophosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylethanolamine and

lysophosphatidylserine, among others (72). These lysophospholipids can increase

lysosomal membrane permeability by disrupting the integrity of the

autolysosome or regulating ion channels, which further disrupts the

fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, leading to a blockade of

autophagic flux (49,73,74).

Fusion disorders between the autophagosome and lysosome result in

impaired degradation of cellular components, promote the

transcription of inflammatory factors and exacerbate cell apoptosis

(75).

The effective role of cPLA2 in

cardiovascular diseases

The preceding section detailed the potential

mechanisms of cPLA2. Below, these mechanisms are associated with

clinical significance in cardiovascular diseases, summarizing the

research progress of cPLA2 in these conditions.

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is the underlying pathology of

cardiovascular diseases (76) and

cPLA2 plays a significant role in this process.

Amplifying inflammatory response

The formation of atherosclerosis is closely

associated with chronic low-grade inflammation (77) and cPLA2 promotes the synthesis of

inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes.

These inflammatory mediators activate endothelial cells, induce the

recruitment of leukocytes and macrophages and initiate local

inflammatory responses. Persistent inflammation promotes lipid

accumulation in the arterial wall and accelerates plaque formation

(56).

Promoting smooth muscle cell

proliferation and migration

cPLA2 also promotes the proliferation and migration

of smooth muscle cells by regulating the release of cytokines. This

plays a critical role in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques

and vascular wall remodeling (13,56).

Blocking autophagic flux

When autophagic flux is impaired, vascular cells

(such as endothelial cells, macrophages and smooth muscle cells)

are unable to effectively clear accumulated harmful substances

(such as oxidized low-density lipoprotein and lipid droplets),

leading to enhanced inflammation, lipid deposition and plaque

formation. This further accelerates the progression of

atherosclerosis (65).

Coronary artery disease

Amplifying inflammatory response

cPLA2 can amplify the inflammatory response within

plaques by promoting the production of inflammatory mediators,

leading to plaque instability and rupture. Following plaque

rupture, thrombosis can be triggered, resulting in acute coronary

syndromes (such as myocardial infarction) (65).

Prothrombotic effect

AA derivatives produced by cPLA2 (such as

thromboxane A2) have a strong prothrombotic effect, promoting

platelet aggregation and thrombosis formation. This creates

favorable conditions for the onset of coronary heart disease

(28).

Myocardial infarction

Exacerbating inflammatory response

After myocardial infarction, the activation of cPLA2

leads to the release of AA, which further synthesizes inflammatory

mediators, such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes. These mediators

promote the infiltration of inflammatory cells (such as macrophages

and leukocytes), aggravating myocardial damage and necrosis, while

delaying myocardial repair (65).

Promoting excessive myocardial cell

apoptosis

During reperfusion therapy following acute

myocardial infarction, excessive activation of cPLA2 may lead to

excessive apoptosis of myocardial cells, exacerbating reperfusion

injury (that is, reperfusion damage), which causes further

myocardial cell death and functional loss (40).

Blocking autophagic flux

cPLA2 inhibits autophagic activity, preventing

myocardial cells from effectively clearing damaged organelles. This

leads to increased cell death, further exacerbating the damage

caused by myocardial infarction (61,62).

Heart failure

Promoting inflammatory response and cell

apoptosis

In heart failure, cPLA2 promotes myocardial cell

apoptosis and fibrosis by activating downstream inflammatory and

fibrosis pathways, leading to the deterioration of cardiac

structure and function. cPLA2 may regulate the activity of

fibroblasts, promoting collagen deposition and increasing the

stiffness of the heart, thereby worsening heart failure (37–39).

Hypertension

Endothelial injury

Increased activity of cPLA2 leads to the breakdown

of phospholipids in endothelial cell membranes, which in turn

affects the vasomotor function of blood vessels (76). Endothelial damage is a key feature

of hypertension and by altering endothelial cell function, cPLA2

may exacerbate endothelial permeability and vascular stiffness

(13), further worsening

hypertension.

Regulation of the renin-angiotensin

system

Studies suggest that cPLA2 may be involved in

regulating the action of angiotensin II (Ang II), a significant

trigger of hypertension (3,78).

By affecting this system, cPLA2 may indirectly contribute to the

elevation of blood pressure.

Valvular heart disease

Triggering inflammatory response and oxidative

stress

In valvular heart diseases (such as rheumatic heart

disease and degenerative valve disease), chronic inflammation over

time leads to the destruction and proliferation of valve tissue

(79) and the activation of cPLA2

exacerbates this process. Increased activity of cPLA2 may intensify

the generation of free radicals, thereby aggravating the

pathological damage in valve disease (1).

Affecting the function of valve

cells

Activation of cPLA2 alters the function of valve

cells (such as fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells), promoting the

proliferation, migration and collagen synthesis of these cells

(37–39). This may lead to pathological

changes such as thickening, calcification and fibrosis of the

valve, thus worsening the progression of valvular heart

disease.

Conclusion and prospects

cPLA2 plays a critical role in the onset and

progression of cardiovascular diseases, particularly in processes

such as inflammatory response, platelet activation, myocardial cell

apoptosis and autophagy. By catalyzing the hydrolysis of

phospholipids to release arachidonic acid, cPLA2 triggers a cascade

of biological reactions that promote inflammation and thrombosis,

thereby exacerbating the progression of atherosclerosis, myocardial

infarction, heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases.

Additionally, cPLA2 holds significant potential as a biomarker,

with its activity guiding early diagnosis (25), risk assessment and prognosis

evaluation in cardiovascular diseases (80,81).

Several studies have shown that inhibiting cPLA2 activity (for

example by using inhibitors such as AACOCF3) can effectively

alleviate inflammation, thrombosis, myocardial damage and other

issues associated with cardiovascular diseases (82–84).

However, its clinical application faces challenges, including lack

of specificity, unstandardized detection methods, limited

large-scale validation and the influence of various external

factors. Moreover, the development of cPLA2 inhibitors shows

promise for clinical treatment, but challenges remain in terms of

selectivity, pharmacokinetics and safety. Preclinical and clinical

trial results (for example LY3159200, developed by Eli Lilly and

Company) have demonstrated promising efficacy in experimental

settings, but further exploration is needed regarding their safety,

long-term effects and side effects (85).

In conclusion, cPLA2 inhibitors represent a novel

therapeutic approach for cardiovascular diseases. Their future

development depends on more precise drug design, comprehensive

clinical validation and thorough evaluation of long-term efficacy.

By addressing existing technological and clinical challenges,

cPLA2-targeted therapies have the potential to offer new treatment

options for cardiovascular disease patients, improve quality of

life and reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present review was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (NSFC) under grant nos. 82300294 and 82202750;

Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant no.

ZR2021QH178); Science and Technology Support Plan for Youth

Innovation of Colleges and Universities of Shandong Province of

China under grant number (grant no. 2023KJ187).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

GS was involved in the conception of the study, and

the formulation and evolution of overarching study goals and aims.

XC was responsible for project administration and article revision.

WL was involved in manuscript preparation, presentation of the

information and figures, and writing the initial draft (including

substantive translation). SW contributed by preparing the

manuscript, specifically its critical review, commentary and

revision at pre-publication stages. RL performed study revisions

and improvements. DZ and XQ drew the table and diagrams and

performed revisions. JZ, ZL and MM were involved in the analysis of

the information. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wang S, Li B, Solomon V, Fonteh A,

Rapoport SI, Bennett DA, Arvanitakis Z, Chui HC, Sullivan PM and

Yassine HN: Calcium-dependent cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation

is implicated in neuroinflammation and oxidative stress associated

with ApoE4. Mol Neurodegener. 17:422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jin W, Zhao J, Yang E, Wang Y, Wang Q, Wu

Y, Tong F, Tan Y, Zhou J and Kang C: Neuronal STAT3/HIF-1α/PTRF

axis-mediated bioenergetic disturbance exacerbates cerebral

ischemia-reperfusion injury via PLA2G4A. Theranostics.

12:3196–3216. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Song CY, Singh P, Motiwala M, Shin JS, Lew

J, Dutta SR, Gonzalez FJ, Bonventre JV and Malik KU:

2-methoxyestradiol ameliorates angiotensin II-induced hypertension

by inhibiting cytosolic phospholipase A2α activity in female mice.

Hypertension. 78:1368–1381. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Jing H, Reed A, Ulanovskaya OA, Grigoleit

JS, Herbst DM, Henry CL, Li H, Barbas S, Germain J, Masuda K and

Cravatt BF: Phospholipase Cγ2 regulates endocannabinoid and

eicosanoid networks in innate immune cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

118:e21129711182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sun GY, Geng X, Teng T, Yang B, Appenteng

MK, Greenlief CM and Lee JC: Dynamic role of phospholipases A2 in

health and diseases in the central nervous system. Cells.

10:29632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dabral D and van den Bogaart G: The roles

of phospholipase A2 in phagocytes. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9:6735022021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang HJ, Chen YT, Hu XL, Cai WT, Wang XY,

Ni WF and Zhou KL: Functions and mechanisms of cytosolic

phospholipase A2 in central nervous system trauma. Neural Regen

Res. 18:258–266. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Li Y, Jones JW, Choi HMC, Sarkar C, Kane

MA, Koh EY, Lipinski MM and Wu J: cPLA2 activation contributes to

lysosomal defects leading to impairment of autophagy after spinal

cord injury. Cell Death Dis. 10:5312019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sarkar C, Jones JW, Hegdekar N, Thayer JA,

Kumar A, Faden AI, Kane MA and Lipinski MM: PLA2G4A/cPLA2-mediated

lysosomal membrane damage leads to inhibition of autophagy and

neurodegeneration after brain trauma. Autophagy. 16:466–485. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hayashi D, Mouchlis VD and Dennis EA: Each

phospholipase A2 type exhibits distinct selectivity toward sn-1

ester, alkyl ether, and vinyl ether phospholipids. Biochim Biophys

Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 1867:1590672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kita Y, Shindou H and Shimizu T: Cytosolic

phospholipase A2 and lysophospholipid acyltransferases. Biochim

Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 1864:838–845. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhang H, Chen Y, Li F, Wu C, Cai W, Ye H,

Su H, He M, Yang L, Wang X, et al: Elamipretide alleviates

pyroptosis in traumatically injured spinal cord by inhibiting

cPLA2-induced lysosomal membrane permeabilization. J

Neuroinflammation. 20:62023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Frąk W, Wojtasińska A, Lisińska W,

Młynarska E, Franczyk B and Rysz J: Pathophysiology of

cardiovascular diseases: New insights into molecular mechanisms of

atherosclerosis, arterial hypertension, and coronary artery

disease. Biomedicines. 10:19382022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hasan S, Ghani N, Zhao X, Good J, Huang A,

Wrona HL, Liu J and Liu CJ: Dietary pyruvate targets cytosolic

phospholipase A2 to mitigate inflammation and obesity in mice.

Protein Cell. 15:661–685. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Huwiler A, Feuerherm AJ, Sakem B,

Pastukhov O, Filipenko I, Nguyen T and Johansen B: The

ω3-polyunsaturated fatty acid derivatives AVX001 and AVX002

directly inhibit cytosolic phospholipase A(2) and suppress PGE(2)

formation in mesangial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 167:1691–1701. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bacher S, Meier-Soelch J, Kracht M and

Schmitz ML: Regulation of transcription factor NF-κB in its natural

habitat: The nucleus. Cells. 10:7532021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Aslani M, Mortazavi-Jahromi SS and

Mirshafiey A: Cytokine storm in the pathophysiology of COVID-19:

Possible functional disturbances of miRNAs. Int Immunopharmacol.

101:1081722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Donohoe F, Wilkinson M, Baxter E and

Brennan DJ: Mitogen-Activated protein kinase (MAPK) and

obesity-related cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 21:12412020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sahana TG and Zhang K: Mitogen-activated

protein kinase pathway in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Biomedicines. 9:9692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ye J, Zhai L, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Chen L, Hu

L, Zhang S and Ding Z: DL-3-n-butylphthalide inhibits platelet

activation via inhibition of cPLA2-mediated TXA2 synthesis and

phosphodiesterase. Platelets. 26:736–744. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu H, Li X, Xie J, Lv C, Lian F, Zhang S,

Duan Y, Zeng Y and Piao X: Gypenoside L and Gypenoside LI Inhibit

proliferation in renal cell carcinoma via regulation of the MAPK

and arachidonic acid metabolism pathways. Front Pharmacol.

13:8206392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lou J, Wang X, Zhang H, Yu G, Ding J, Zhu

X, Li Y, Wu Y, Xu H, Xu H, et al: Inhibition of PLA2G4E/cPLA2

promotes survival of random skin flaps by alleviating lysosomal

membrane permeabilization-induced necroptosis. Autophagy.

18:1841–1863. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Peng Z, Chang Y, Fan J, Ji W and Su C:

Phospholipase A2 superfamily in cancer. Cancer Lett. 497:165–177.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chen Y, Zhang H, Jiang L, Cai W, Kuang J,

Geng Y, Xu H, Li Y, Yang L, Cai Y, et al: DADLE promotes motor

function recovery by inhibiting cytosolic phospholipase

A2 mediated lysosomal membrane permeabilization after

spinal cord injury. Br J Pharmacol. 181:712–734. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chang Y, Hsia CW, Chiou KR, Yen TL,

Jayakumar T, Sheu JR and Huang WC: Eugenol: A potential modulator

of human platelet activation and mouse mesenteric vascular

thrombosis via an innovative cPLA2-NF-κB signaling axis.

Biomedicines. 12:16892024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Khan SA and Ilies MA: The phospholipase A2

superfamily: Structure, isozymes, catalysis, physiologic and

pathologic roles. Int J Mol Sci. 24:13532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Elinder LS, Dumitrescu A, Larsson P, Hedin

U, Frostegård J and Claesson HE: Expression of phospholipase A2

isoforms in human normal and atherosclerotic arterial wall.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 17:2257–2263. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Badimon L, Vilahur G, Rocca B and Patrono

C: The key contribution of platelet and vascular arachidonic acid

metabolism to the pathophysiology of atherothrombosis. Cardiovasc

Res. 117:2001–2015. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Szczuko M, Kozioł I, Kotlęga D, Brodowski

J and Drozd A: The role of thromboxane in the course and treatment

of ischemic stroke: Review. Int J Mol Sci. 22:116442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hong HJ, Nam GS and Nam KS: Daidzein

inhibits human platelet activation by downregulating thromboxane

A2 production and granule release, regardless of COX-1

activity. Int J Mol Sci. 24:119852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Liu G, Yuan Z, Tian X, Xiong X, Guo F, Lin

Z and Qin Z: Pimpinellin inhibits collagen-induced platelet

aggregation and activation through inhibiting granule secretion and

PI3K/Akt pathway. Front Pharmacol. 12:7063632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bertheloot D, Latz E and Franklin BS:

Necroptosis, pyroptosis and apoptosis: An intricate game of cell

death. Cell Mol Immunol. 18:1106–1121. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Rodríguez JP, Leiguez E, Guijas C, Lomonte

B, Gutiérrez JM, Teixeira C, Balboa MA and Balsinde J: A lipidomic

perspective of the action of group IIA secreted phospholipase A2 on

human monocytes: LIPID droplet biogenesis and activation of

cytosolic phospholipase A2α. Biomolecules. 10:8912020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Paloschi MV, Lopes JA, Boeno CN, Silva

MDS, Evangelista JR, Pontes AS, da Silva Setúbal S, Rego CMA, Néry

NM, Ferreira AA, et al: Cytosolic phospholipase A2-α participates

in lipid body formation and PGE2 release in human neutrophils

stimulated with an l-amino acid oxidase from calloselasma

rhodostoma venom. Sci Rep. 10:109762020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Boi R, Ebefors K, Henricsson M, Johansson

A, Borén J and Nyström J: MO614: Modified lipid metabolism and

cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation in mesangial cells under

pro-inflammatory conditions. Nephrol Dial Transplant. May

3–2022.(Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfac076.007, 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Bayır H, Anthonymuthu TS, Tyurina YY,

Patel SJ, Amoscato AA, Lamade AM, Yang Q, Vladimirov GK, Philpott

CC and Kagan VE: Achieving life through death: Redox biology of

lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis. Cell Chem Biol. 27:387–408.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Li D, Chen A, Lan T, Zou Y, Zhao L, Yang

P, Qu H, Wei L, Varghese Z, Moorhead JF, et al: SCAP knockdown in

vascular smooth muscle cells alleviates atherosclerosis plaque

formation via up-regulating autophagy in ApoE-/- mice. FASEB J.

33:3437–3450. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Canty JM Jr: Myocardial injury, troponin

release, and cardiomyocyte death in brief ischemia, failure, and

ventricular remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.

323:H1–H15. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Pesce M, Duda GN, Forte G, Girao H, Raya

A, Roca-Cusachs P, Sluijter JPG, Tschöpe C and Van Linthout S:

Cardiac fibroblasts and mechanosensation in heart development,

health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 20:309–324. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Dong Y, Chen H, Gao J, Liu Y, Li J and

Wang J: Molecular machinery and interplay of apoptosis and

autophagy in coronary heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 136:27–41.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Naik MU, Patel P, Derstine R, Turaga R,

Chen X, Golla K, Neeves KB, Ichijo H and Naik UP: Ask1 regulates

murine platelet granule secretion, thromboxane A2 generation, and

thrombus formation. Blood. 129:1197–1209. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yue J and López JM: Understanding MAPK

signaling pathways in apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 21:23462020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Xuan C, Jin C, Jin Z and Chi Y: The

protective effects of glutamine against bronchopulmonary dysplasia

are associated with MKP-1/MAPK/cPLA2 signalingmediated NF-kappaB

pathway. Gen Physiol Biophys. 42:229–239. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Davidovich P, Higgins CA, Najda Z, Longley

DB and Martin SJ: cFLIPL acts as a suppressor of TRAIL- and

Fas-initiated inflammation by inhibiting assembly of

caspase-8/FADD/RIPK1 NF-κB-activating complexes. Cell Rep.

42:1134762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Mustafa M, Ahmad R, Tantry IQ, Ahmad W,

Siddiqui S, Alam M, Abbas K, Moinuddin, Hassan MI, Habib S and

Islam S: Apoptosis: A comprehensive overview of signaling pathways,

morphological changes, and physiological significance and

therapeutic implications. Cells. 13:18382024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Whitaker RH and Cook JG: Stress relief

techniques: p38 MAPK determines the balance of cell cycle and

apoptosis pathways. Biomolecules. 11:14442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang A, Jiang H, Liu Y, Chen J, Zhou X,

Zhao C, Chen X and Lin M: Rhein induces liver cancer cells

apoptosis via activating ROS-dependent JNK/Jun/caspase-3 signaling

pathway. J Cancer. 11:500–507. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ke Z, Lu J, Zhu J, Yang Z, Jin Z and Yuan

L: Down-regulation of lincRNA-EPS regulates apoptosis and autophagy

in BCG-infected RAW264.7 macrophages via JNK/MAPK signaling

pathway. Infect Genet Evol. 77:1040772020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zheng N, Li H, Wang X, Zhao Z and Shan D:

Oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis is associated with

dysregulated Akt/p53 signaling pathway. J Recept Signal Transduct

Res. 40:599–604. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zou H and Liu G: Inhibition of endoplasmic

reticulum stress through activation of MAPK/ERK signaling pathway

attenuates hypoxia-mediated cardiomyocyte damage. J Recept Signal

Transduct Res. 41:532–537. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Xu F, Na L, Li Y and Chen L: Roles of the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathways in neurodegenerative diseases and

tumours. Cell Biosci. 11:1572020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Qin W, Cao L and Massey IY: Role of

PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in cardiac fibrosis. Mol Cell Biochem.

476:4045–4059. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Peng Y, Wang Y, Zhou C, Mei W and Zeng C:

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and its role in cancer therapeutics: Are we

making headway? Front Oncol. 12:8191282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Chen J, Tang H, Hay N, Xu J and Ye RD: Akt

isoforms differentially regulate neutrophil functions. Blood.

115:4237–4246. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Lin WC, Chuang YC, Chang YS, Lai MD, Teng

YN, Su IJ, Wang CC, Lee KH and Hung JH: Endoplasmic reticulum

stress stimulates p53 expression through NF-κB activation. PLoS

One. 7:e391202012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Cheng W, Cui C, Liu G, Ye C, Shao F,

Bagchi AK, Mehta JL and Wang X: NF-κB, A potential therapeutic

target in cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther.

37:571–584. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Liu S, Yao S, Yang H, Liu S and Wang Y:

Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 14:6482023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhang XW, Lv XX, Zhou JC, Jin CC, Qiao LY

and Hu ZW: Autophagic flux detection: Significance and methods

involved. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1208:131–173. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Mi S, Huang F, Jiao M, Qian Z, Han M, Miao

Z and Zhan H: Inhibition of MEG3 ameliorates cardiomyocyte

apoptosis and autophagy by regulating the expression of

miRNA-129-5p in a mouse model of heart failure. Redox Rep.

28:22246072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Wu X, Liu Z, Yu XY, Xu S and Luo J:

Autophagy and cardiac diseases: Therapeutic potential of natural

products. Med Res Rev. 41:314–341. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Che Y, Wang Z, Yuan Y, Zhou H, Wu H, Wang

S and Tang Q: By restoring autophagic flux and improving

mitochondrial function, corosolic acid protects against Dox-induced

cardiotoxicity. Cell Biol Toxicol. 38:451–467. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wang Q, Su H and Liu J: Protective effect

of natural medicinal plants on cardiomyocyte injury in heart

failure: Targeting the dysregulation of mitochondrial homeostasis

and mitophagy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022:36170862022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Gao J, Chen X, Shan C, Wang Y, Li P and

Shao K: Autophagy in cardiovascular diseases: Role of noncoding

RNAs. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 23:101–118. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Wang L, Wang J, Cretoiu D, Li G and Xiao

J: Exercise-mediated regulation of autophagy in the cardiovascular

system. J Sport Health Sci. 9:203–210. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Miao J, Zang X, Cui X and Zhang J:

Autophagy, hyperlipidemia, and atherosclerosis. Adv Exp Med Biol.

1207:237–264. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Yun HR, Jo YH, Kim J, Shin Y, Kim SS and

Choi TG: Roles of autophagy in oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci.

21:32892020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Frias MA, Hatipoglu A and Foster DA:

Regulation of mTOR by phosphatidic acid. Trends Endocrinol Metab.

34:170–180. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Sukumaran P, Da Conceicao VN, Sun Y,

Ahamad N, Saraiva LR, Selvaraj S and Singh BB: Calcium signaling

regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cells. 10:21252021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Liu Y, Yang Q, Chen S, Li Z and Fu L:

Targeting VPS34 in autophagy: An update on pharmacological

small-molecule compounds. Eur J Med Chem. 256:1154672023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Foster KG and Fingar DC: Mammalian target

of rapamycin (mTOR): Conducting the cellular signaling symphony. J

Biol Chem. 285:14071–14077. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Gao G, Chen W, Yan M, Liu J, Luo H, Wang C

and Yang P: Rapamycin regulates the balance between cardiomyocyte

apoptosis and autophagy in chronic heart failure by inhibiting mTOR

signaling. Int J Mol Med. 45:195–209. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Jiang S, Yang H and Li M: Emerging roles

of lysophosphatidic acid in macrophages and inflammatory diseases.

Int J Mol Sci. 24:125242023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Wang ML, Zhang YJ, He DL, Li T, Zhao MM

and Zhao LM: Inhibition of PLA2G4A attenuated valproic acid-induced

lysosomal membrane permeabilization and restored impaired

autophagic flux: Implications for hepatotoxicity. Biochem

Pharmacol. 227:1164382024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Yang HL, Lai ZZ, Shi JW, Zhou WJ, Mei J,

Ye JF, Zhang T, Wang J, Zhao JY, Li DJ and Li MQ: A defective

lysophosphatidic acid-autophagy axis increases miscarriage risk by

restricting decidual macrophage residence. Autophagy. 18:2459–2480.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Ballabio A and Bonifacino JS: Lysosomes as

dynamic regulators of cell and organismal homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 21:101–118. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Kotlyarov S: Immune function of

endothelial cells: Evolutionary aspects, molecular biology and role

in atherogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 23:97702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Gusev E and Sarapultsev A: Atherosclerosis

and inflammation: Insights from the theory of general pathological

processes. Int J Mol Sci. 24:79102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Singh P, Song CY, Dutta SR, Pingili A,

Shin JS, Gonzalez FJ, Bonventre JV and Malik KU:

6β-Hydroxytestosterone promotes angiotensin II-induced hypertension

via enhanced cytosolic phospholipase A2α activity. Hypertension.

78:1053–1066. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Passos LSA, Nunes MCP and Aikawa E:

Rheumatic heart valve disease pathophysiology and underlying

mechanisms. Front Cardiovasc Med. 7:6127162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Zhang H, Gao Y, Wu D and Zhang D: The

relationship of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 activity

with the seriousness of coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc

Disord. 20:2952020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Verdoia M, Rolla R, Gioscia R, Rognoni A

and De Luca G; Novara Atherosclerosis Study Group (NAS), :

Lipoprotein associated- phospholipase A2 in STEMI vs. NSTE-ACS

patients: A marker of cardiovascular atherosclerotic risk rather

than thrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 56:37–44. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Yigit E, Deger O, Korkmaz K, Yigit MH,

Uydu HA, Mercantepe T and Demir S: Propolis reduces inflammation

and dyslipidemia caused by high-cholesterol diet in mice by

lowering ADAM10/17 activities. Nutrients. 16:18612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Ashcroft FJ, Mahammad N, Flatekvål HM,

Feuerherm AJ and Johansen B: cPLA2α enzyme inhibition attenuates

inflammation and keratinocyte proliferation. Biomolecules.

10:14022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Schanstra JP, Luong TTD, Makridakis M, Van

Linthout S, Lygirou V, Latosinska A, Alesutan I, Boehme B, Schelski

N, Von Lewinski D, et al: Systems biology identifies cytosolic PLA2

as a target in vascular calcification treatment. JCI Insight.

4:e1256382019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Huang JP, Cheng ML, Wang CH, Huang SS,

Hsieh PS, Chang CC, Kuo CY, Chen KH and Hung LM: Therapeutic

potential of cPLA2 inhibitor to counteract dilated-cardiomyopathy

in cholesterol-treated H9C2 cardiomyocyte and MUNO rat. Pharmacol

Res. 160:1052012020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|