Ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) is a clinical

phenomenon encountered in conditions such as myocardial infarction,

stroke, organ transplantation and surgical intervention. In these

contexts, tissues or organs undergo ischemia due to compromised

blood supply, followed by irreversible damage following reperfusion

(1). The pathophysiology of IRI

typically unfolds in several key stages: i) During ischemia, tissue

is deprived of oxygen, leading to hypoxia and the accumulation of

metabolites; this results in a notable decline in intracellular ATP

levels, impairing cellular function and culminating in cell death;

ii) in the reperfusion phase, restoration of blood flow

re-establishes oxygenation but the sudden influx of oxygen may

initiate a cascade of detrimental reactions, including oxidative

stress and release of inflammatory mediators. These responses

exacerbate cell injury, intensifying tissue necrosis and functional

deterioration (2). Studies on the

role of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH)2 in IRI are summarized in

Table I (3–25).

Ferroptosis is a more recently identified form of

regulated cell death (RCD), characterized by intracellular iron

accumulation and subsequent oxidative stress, which induces both

apoptosis and necrosis (32). IRI

triggers release and accumulation of intracellular iron, amplifying

cellular damage through oxidative stress and promoting inflammatory

responses (32). While the

mechanisms of ferroptosis in IRI are complex, its key role in the

injury cascade has been well-established (32,33).

As such, targeting ferroptosis regulation has emerged as a

promising strategy for mitigating IRI (33).

IRI is a multifaceted process that involves a range

of cellular and molecular alterations. Despite application of

certain therapeutic interventions in clinical practice, such as

antioxidants (vitamin E, vitamin C and N-acetylcysteine),

anti-inflammatory (corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs), Calcium Channel Blockers (verapamil, dantrolene) effective

treatment for IRI remains challenging. Thus, the identification of

novel therapeutic targets and strategies is essential. Recent

research underscores the importance of RCD pathways, particularly

ferroptosis, in the pathogenesis of IRI (2,34).

However, the mechanisms that regulate ferroptosis during IRI remain

poorly understood. The present review aimed to summarize the roles

of ALDH2 and ferroptosis in the context of IRI. ALDH2 has been

proposed as a key regulator of ferroptosis. By detoxifying reactive

aldehydes and preventing lipid peroxidation (LPO), ALDH2 may

influence ferroptosis, thereby modulating severity of IRI (35,36).

Additionally, ALDH2 regulates other forms of programmed cell death

(20,37). The present aimed to review

summarize these pathways to identify potential commonalities in

ALDH2 regulation of ferroptosis and the mechanisms underlying

cellular damage and inflammation to provide insight into their

potential therapeutic applications. Through a comprehensive

examination of ALDH2 and ferroptosis, the present review aims to

provide a theoretical framework for development of innovative

treatments and pharmacotherapies to improve clinical outcomes.

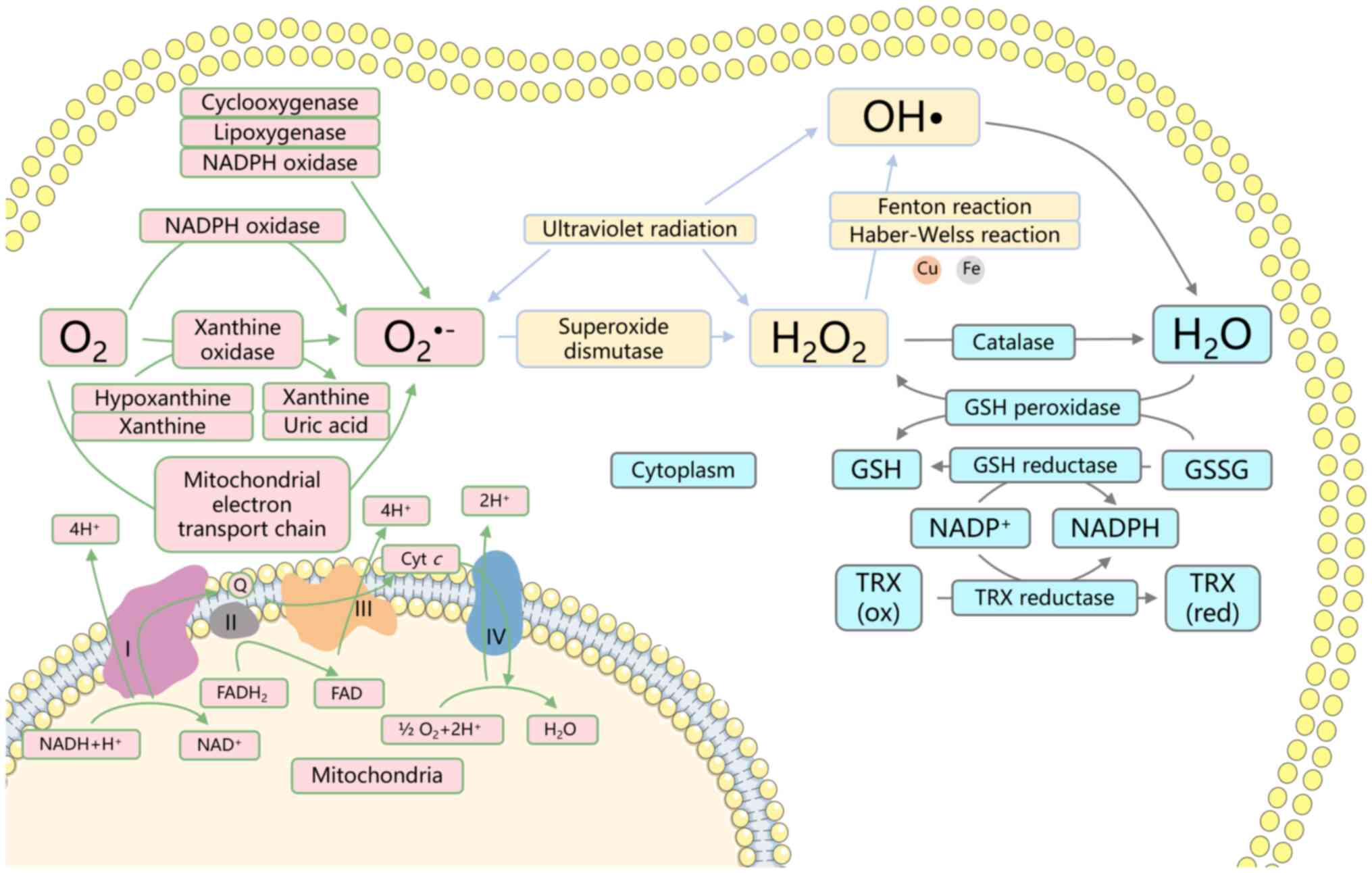

ROS are highly reactive molecules, such as

superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

and hydroxyl radicals (OH•), produced as byproducts of normal cell

metabolism (38) (Fig. 1). However, excessive ROS

accumulation can lead to oxidative stress and damage to proteins,

lipids and DNA, which results in cellular injury and potentially

cell death. ALDH2 functions as a potent scavenger of ROS (26). By degrading toxic aldehydes, ALDH2

decreases intracellular aldehyde levels, mitigating their harmful

effects on cellular integrity (39). Aldehydes, with strong oxidative

potential, bind and oxidize cellular macromolecules, including

proteins and DNA, thereby inducing cell damage. Additionally,

during the conversion of acetaldehyde to acetic acid, ALDH2

catalyzes the reduction of NAD+ to NADH (40). NADH serves as a substrate for

mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I, promoting oxidative

phosphorylation and enhancing the efficiency of redox reactions,

which limits ROS production. Furthermore, elevated ROS levels can

influence ALDH2 activity and stability (41,42),

establishing a feedback loop that modulates ALDH2 function.

In IRI, evidence highlights the role of ALDH2 in

mitigating ROS production and protecting tissues and organs

(18,20). In rat diabetic myocardial IRI and

H9C2 cardiomyocyte hypoxia-reoxygenation models, Tan et al

(18) observed that ALDH2

upregulation decreases mitochondrial ROS levels. This facilitates

maintenance of mitochondrial dynamics, preserving the balance

between fusion and fission and stabilizing mitochondrial

morphology. Xu et al (20)

revealed that ALDH2 activation promotes autophagy by increasing the

phosphorylation of Beclin-1 at Ser90. This autophagy activation

maintains cellular and tissue homeostasis by reducing ROS levels

and clearing damaged organelles. These findings underscore the

multifaceted protective mechanisms mediated by ALDH2 in IRI, from

ROS reduction to preservation of mitochondrial dynamics and

promotion of autophagy. These insights contribute to understanding

of the complex interactions between ALDH2 and IRI, offering a

foundation for development of targeted therapeutic interventions

aimed at reducing tissue damage and improving clinical

outcomes.

LPO is a key feature of IRI. Elevated ROS levels

within cells directly target lipids, with unchecked oxidative

stress disrupting the balance between ROS production and clearance,

leading to accumulation of endogenous ROS (43). Of ROS species involved in LPO,

hydroxyl and hydroperoxyl radicals are primary contributors. These

radicals attack the carbon-carbon double bonds of polyunsaturated

phospholipids in membranes, triggering a cascade of oxidation that

compromises membrane integrity and impairs membrane functionality

(44–46).

Membrane lipids, primarily composed of polar

glycerophospholipids, are susceptible to oxidative damage. Cell

membranes contain notable amounts of polyunsaturated lipids, which

are vulnerable during IR, a phase in which mitochondria become the

principal site of ROS generation (47). ROS interact with polyunsaturated

phospholipids in mitochondrial membranes, forming lipid

hydroperoxides. Secondary reactions produce >200 types of highly

reactive lipid-derived aldehydes (LDAs), such as 4-HNE, MDA,

4-oxononenal, acrolein, crotonaldehyde and methylglyoxal (47). These LDAs not only serve as ROS

byproducts but also further stimulate ROS production in

mitochondria, intensifying tissue damage through a positive

feedback loop. Consequently, excess aldehydes and ROS diffuse from

mitochondria to other cell compartments, precipitating protein

dysfunction, DNA damage and gene mutations, contributing to a range

of diseases, including cardiovascular conditions, cancer, diabetes,

osteoporosis and neurodegenerative disorder (48).

As markers of oxidative stress, 4-HNE and MDA are

among the most potent reactive aldehydes (49). ALDH2 serves a key role in their

detoxification by metabolizing MDA to malonic acid or acetaldehyde

and converting 4-HNE to 4-hydroxy-2-nonenic acid. By reducing the

accumulation of these toxic aldehydes, ALDH2 contributes to

mitigating oxidative stress (49).

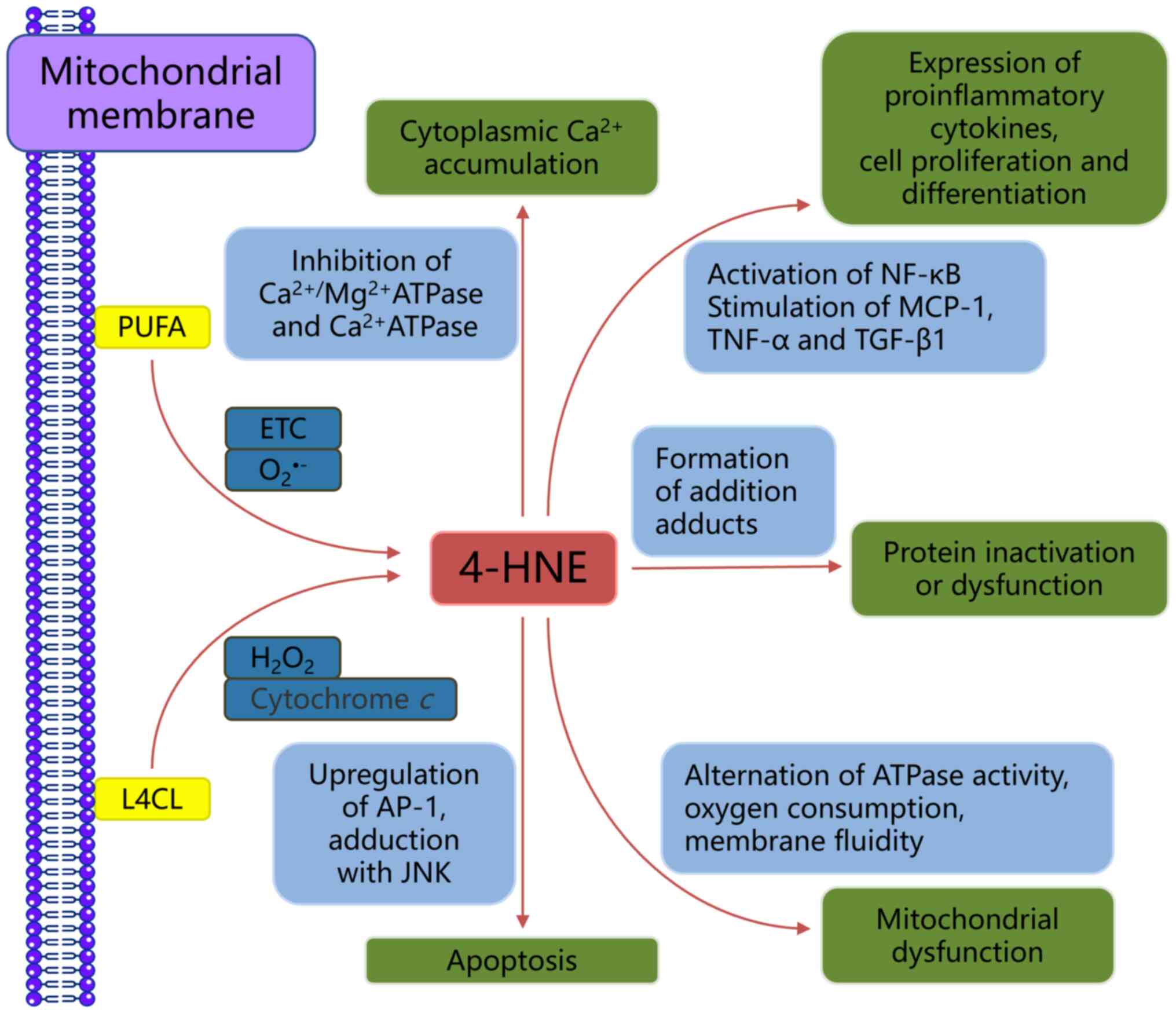

As aforementioned, 4-HNE results from LPO, with ω-6

polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) such as linoleic, γ-linolenic

and arachidonic acid (AA) serving as precursors under oxidative

stress mediated by ROS (50)

(Fig. 2). 4-HNE primarily targets

reduction-associated signaling molecules and upstream regulatory

proteins, including thioredoxin (an intracellular ROS scavenger)

and glutathione (GSH) (51).

Additionally, 4-HNE affects protein post-translational

modifications and gene expression: It upregulates the expression of

transcription factors such as NF-κB and activating protein-1, which

regulate genes involved in cell proliferation and differentiation

(52). Moreover, 4-HNE activates

transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

(Nrf2), which transactivates antioxidant response elements and

enhances the expression of genes that are key for cell antioxidant

defense and modulation of oxidative stress. Notable genes regulated

by Nrf2 include hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1), ALDH, glutathione

S-transferase, multidrug resistance protein, aldo-keto reductase,

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate: quinone oxidoreductase

(NQO1) and glutamate-cysteine ligase (53).

4-HNE is implicated in a range of oxidative

stress-associated diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders,

macular degeneration, cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis,

metabolic syndrome and cancer. In these pathological conditions,

4-HNE transcends its role as an oxidative stress marker to become a

key pathogenic factor (54).

Accumulation of 4-HNE has been detected in various types of tissue

during IRI such as heart, brain and intestine. ALDH2 has a key role

in neutralizing 4-HNE; loss of ALDH2 function exacerbates

myocardial cell ferroptosis induced by iron overload, whereas ALDH2

activation mitigates ferroptosis (35). Furthermore, compounds such as

isorhapontigenin have shown efficacy in decreasing oxidative damage

in brain IRI through the PKCε/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, markedly lowering

ROS generation and 4-HNE and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine levels

(55). Similar protective effects

have been observed in intestinal IRI, where administration of

corilagin, an IRI protectant, reduces 4-HNE levels and ferroptosis

(56). 4-HNE can react with

various cellular components, forming adducts that contribute to

tissue damage. Numerous studies have revealed the protective role

of ALDH2 in IRI by effectively removing 4-HNE (18,57).

Transgenic mice with impaired ALDH2 2*2 activity show elevated

4-HNE and GSH levels, along with decreased resistance to acute

oxidative stress induced by IR (57). Additionally, recent evidence has

highlighted the ability of ALDH2 to improve cardiac hemodynamic

parameters and reduce myocardial injury by lowering 4-HNE levels

and inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening

(18). In liver IRI,

supplementation of ALDH2 activator Alda-1 reduces 4-HNE

accumulation, reverses mitochondrial damage and decreases

hepatocyte apoptosis (11). These

findings underscore the key role of ALDH2 in mitigating harmful

effects of 4-HNE accumulation in IRI in various tissues and

organs.

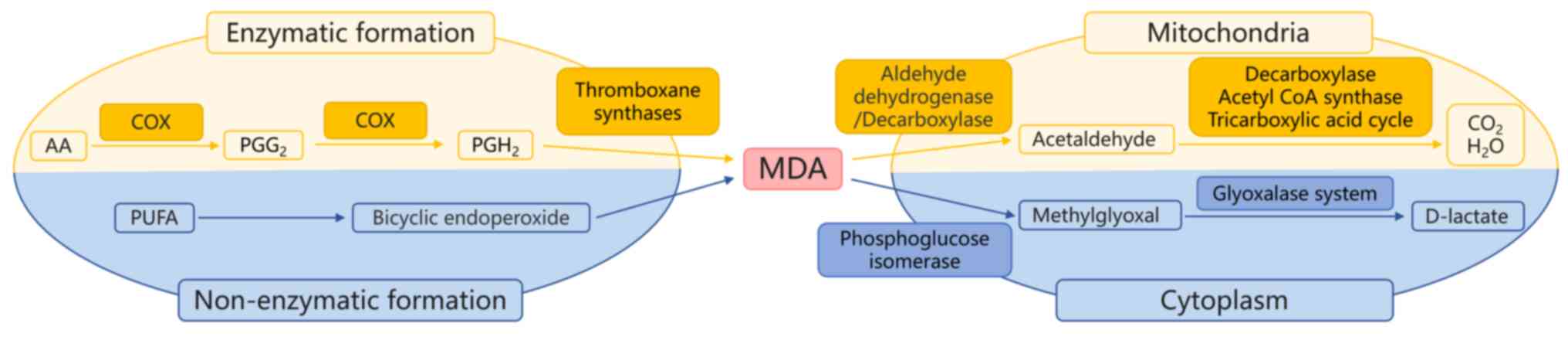

PUFAs, including AA and docosahexaenoic acid, serve

as precursors for MDA generation. PUFAs with ≥2

methylene-interrupted double bonds are susceptible to oxidative

degradation, resulting in MDA production (58) (Fig.

3). Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) assay, initially developed by

food chemists to assess the rancidity of Ω-3 and −6 fatty acids, is

commonly used for the colorimetric or fluorometric determination of

MDA and MDA-like substances (59).

However, TBA reacting substances test lacks specificity. Treatment

of biological samples with TBA may generate complexes with similar

colors to the TBA-MDA complex, potentially confounding

quantification of MDA. Furthermore, MDA or MDA-like substances are

derived from various precursors produced during LPO, including

oxidized lipids, 2-alkenals and 2,4-alkadienals (58).

While MDA is the primary aldehyde generated during

LPO, production of 4-HNE constitutes only 10% of MDA (60). Despite this, the role of MDA as a

signaling molecule and gene expression regulator remains is

understudied compared with 4-HNE. MDA, however, has gained

attention as a biomarker in various types of disease, including

cancer, cardiovascular diseases and neurodegenerative disorders,

with its levels in blood, urine and exhaled breath condensate used

for disease detection (61,62).

MDA-modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles serve a key

role in atherosclerosis pathogenesis (63). These modified LDL particles are

efficiently recognized and internalized by vascular wall

macrophages by scavenger receptors, leading to accumulation in

lipid vesicles. The subsequent engulfment of MDA-modified LDLs by

macrophages results in foam cell formation, initiating lipid

deposition in the vascular wall, which represents early

atherosclerotic lesions (63).

Moreover, MDA conjugates with autologous biomolecules to generate

neo-self epitopes, which interact with the innate immune system.

Effects of various MDA epitopes are mediated via protein kinase C

pathways, including PI3K, Src kinase, phospholipase C/inositol

trisphosphate (IP3), Erk 1/2, spleen tyrosine kinase and NF-κB

(64). These findings underscore

the multifaceted role of MDA in disease pathogenesis and immune

modulation, positioning it as a potential therapeutic target in

various pathological conditions.

MDA undergoes enzymatic metabolism, with the ALDH

family in mitochondria serving a central role in its degradation.

Initially, MDA is oxidized to acetaldehyde by ALDH, which is

further oxidized to acetate. Acetate is then converted to carbon

dioxide and water. Alternatively, MDA metabolism occurs via

GSH-mediated pathways, where phosphoglucose isomerase uses GSH as a

cofactor to convert MDA to methylglyoxal (MG) in the cytoplasm. MG

is metabolized to D-lactate by the glyoxalase system enzymes

(65) (Fig. 3). In the context of IRI, elevated

oxidative stress in cells triggers considerable MDA production,

contributing to tissue and organ dysfunction. Modulating up- and

downstream molecular pathways to attenuate MDA production can

markedly alleviate IRI severity (66,67).

In cerebral IRI, reducing MDA production and inflammatory mediators

alleviates brain tissue damage by inhibiting phosphorylation and

nuclear translocation of NF-κB (66). Similarly, in the liver, the

Nrf2/solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11)-HO-1 axis

regulates MDA production and inhibits ferroptosis (67). The role of MDA in cardiac IRI has

been extensively studied, revealing that inhibiting ROS production

and MDA levels and enhancing superoxide dismutase activity

mitigates oxidative stress in vitro (5,68).

These interventions also inhibit ferroptosis and reduce apoptotic

protein levels (68). The cell MDA

levels are associated with ALDH2 activity, with animal models of

acute lung injury (69), cardiac

reperfusion (5) and liver IR

(11) demonstrating a negative

regulatory association between ALDH2 activity and MDA levels.

4-HNE and MDA are among the most potent and

extensively studied aldehydes in IRI (18,57,60,66,67).

ALDH2 exhibits varying sensitivity to LPO-derived aldehydes, with

the highest efficacy in oxidizing 4-HNE, acrolein and MDA (70). To the best of our knowledge,

however, research on ALDH2 and toxic aldehydes predominantly

focuses on the heart (5,18,35,68),

with limited studies on other organs such as the brain, intestine,

kidney and liver. Although the pathophysiological mechanisms of IRI

are largely similar across different types of tissue, structural

and functional differences in various organs result in distinct

responses to oxidative stress. While several studies document

decreased ALDH2 activity during oxidative stress (1,26,31),

ALDH2 activity remains stable (71). Thus, investigating ALDH2

alterations in different tissues to enable the development of

targeted therapeutic strategies is key. By exploring the

differential responses of ALDH2 to oxidative stress in different

types of tissues, valuable insights can be gained into

tissue-specific vulnerability, leading to tailored interventions

aimed at mitigating IRI. This underscores the need for continued

research to unravel the complex interactions between ALDH2 and

oxidative stress in diverse physiological contexts.

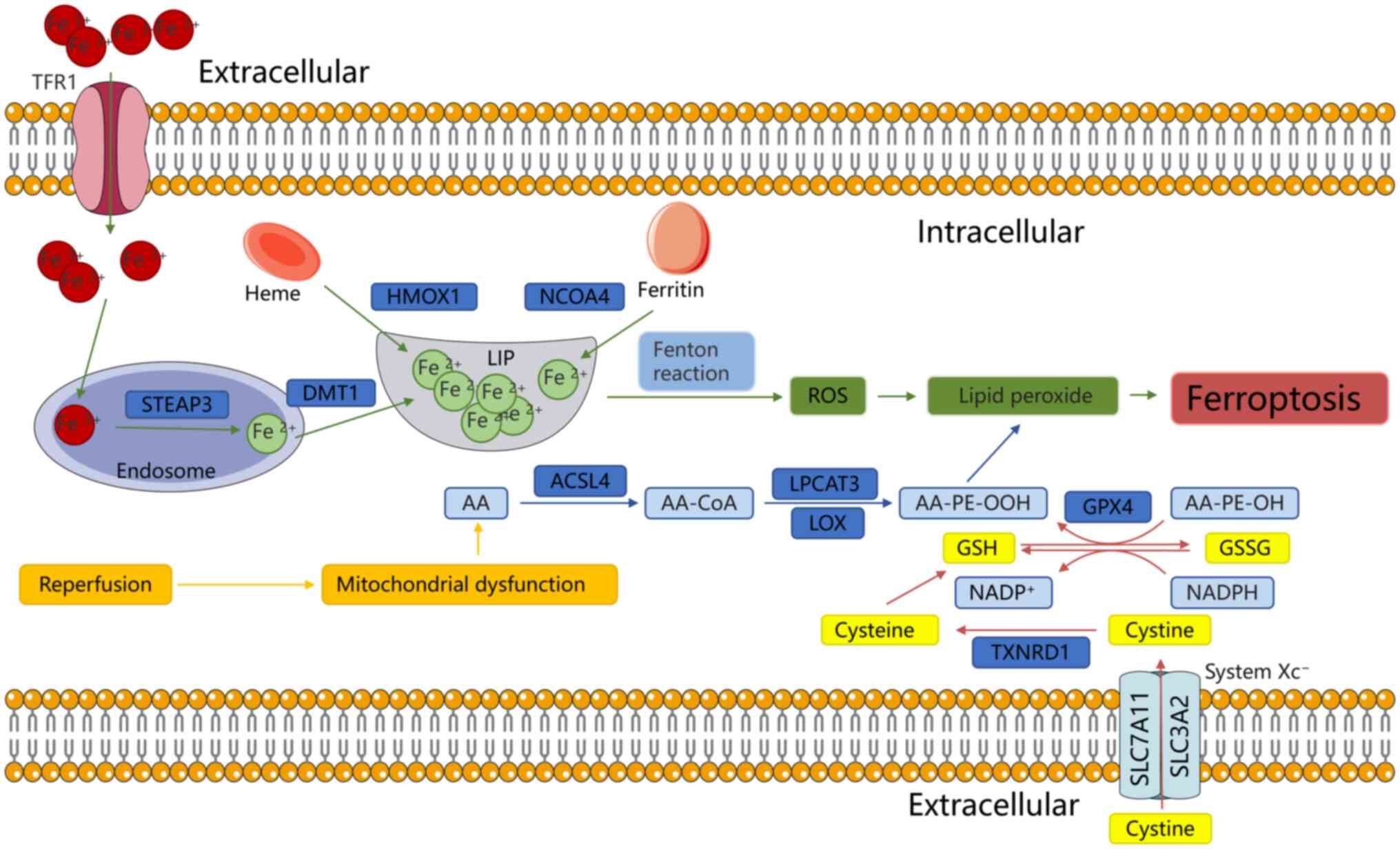

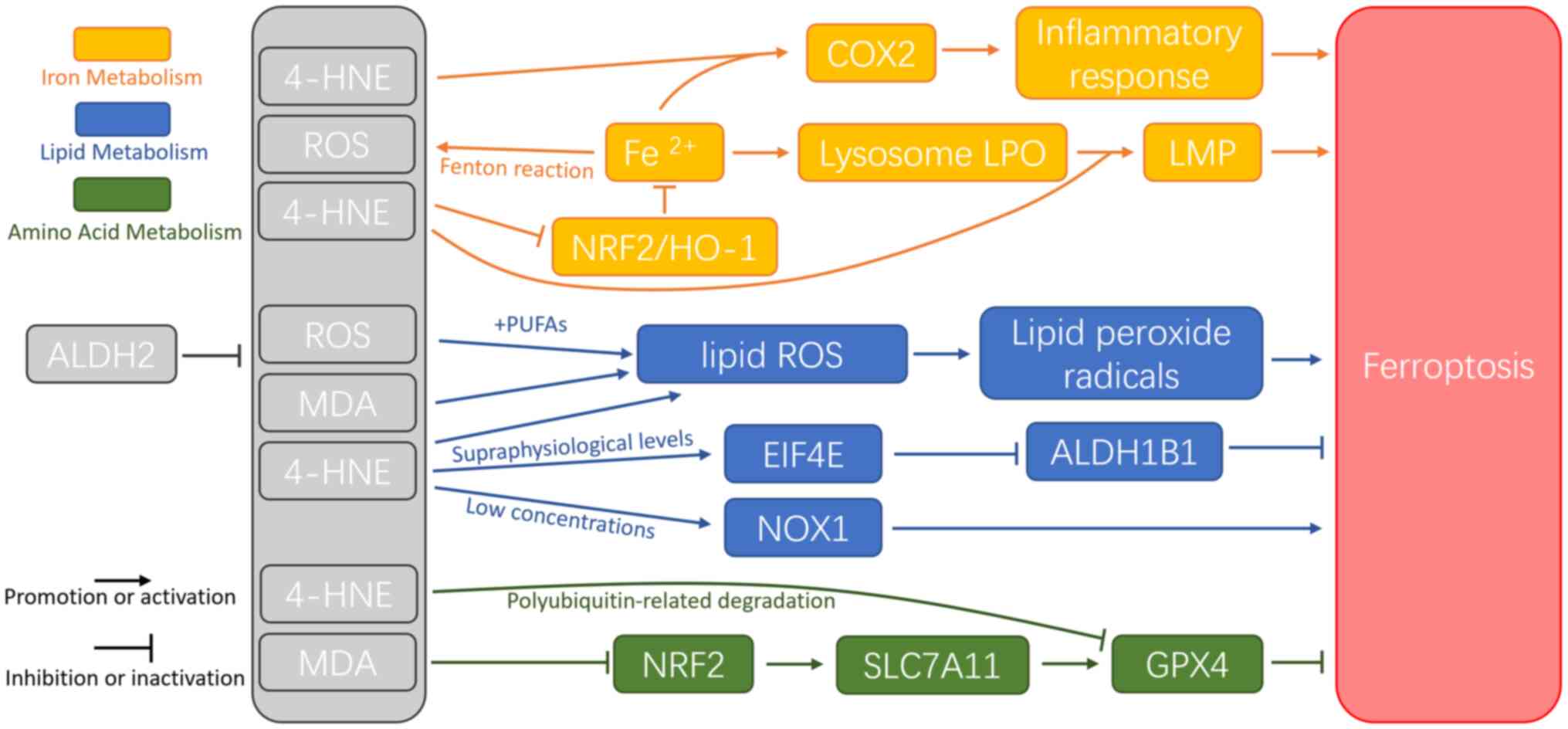

Ferroptosis is a more recently identified

iron-dependent form of RCD, characterized by excessive ROS

accumulation and LPO (32). During

IRI, ferroptosis predominantly occurs during the reperfusion phase

rather than the ischemic phase (72), marked by GSH depletion and

inactivation of GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4) (32). Ferroptosis is the primary form of

cell death during IR in various organs, including the brain, kidney

and heart (73). The mechanisms

underlying ferroptosis involve numerous interconnected pathways,

including lipid, iron and amino acid metabolism (74) (Fig.

4).

Lipid metabolism serves a key role in ferroptosis

during IRI. LPO is initiated by the oxidation of PUFAs,

particularly AA-containing phosphatidylethanolamine (AA-PE)

(75). ROS generated by the Fenton

reaction contribute to LPO (76).

PUFAs exhibit a high affinity for ROS, such as OH• and

H2O2, which remove hydrogen atoms from PUFAs,

generating lipid ROS. These lipid radicals are further oxidized to

lipid peroxide radicals (LOO−) or AA-OOH-PE (77). When the reduction system fails to

neutralize excess of LOO•, ferroptosis is triggered (78,79).

In mice, ischemia induces arachidonic acid 15-lipoxygenase to

oxidize AA-PE into oxidized phosphatidylethanolamines, which,

following reperfusion, initiate LPO and promote ferroptosis

(72). Lipoxygenases (LOXs)

catalyze generation of ROS (34)

and oxidation of AA-PE to AA-OOH-PE (80); while LOXs are considered to be

iron-dependent enzymes (81),

another study has reported iron-oxidizing phospholipids independent

of LOXs (82). In IRI, expression

of LOX increases with extended reperfusion, reaching a peak at 5 h

post-reperfusion (83). The

accumulation of toxic aldehydes, such as 4-HNE and MDA, also serve

a key role in ferroptosis (35).

Biomarkers such as MDA levels, the glutathione disulfide (GSSG)

ratio and Fe2+ and ROS levels are used to assess

ferroptosis in cells (84,85). Additionally, 4-HNE impedes the

accumulation of ALDH1 family member B1 by activating eukaryotic

initiation factor 4E and induces ferroptosis by activating NADPH

oxidase 1 (86).

Iron serves a dual role in ferroptosis: It promotes

ROS accumulation via the Fenton reaction and serves as a key

element in enzymes such as LOXs. The Fenton reaction accelerates

production of OH•; excessive OH• exacerbates LPO, yielding 4-HNE

and activating cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2). COX2, a pro-inflammatory

enzyme, triggers cellular inflammation and may be released into the

extracellular space by vesicles (87,88).

Furthermore, 4-HNE induces mitochondrial dysfunction by binding to

mitochondrial proteins, leading to electron leakage and increased

ROS production. This activates NRF2-mediated antioxidant responses

(88).

Iron overload serves a key role in ferroptosis

through several mechanisms. i) HO-1 catalyzes release of

Fe2+ from hemoglobin, contributing to iron overload

(89); ii) nuclear receptor

coactivator 4 (NCOA4) mediates ferritin degradation by autophagy

(ferritinophagy), releasing free iron (90) iii) transferrin receptor protein 1

(TFR1) induces ferroptosis during IRI, with p53 promoting TFR1

upregulation through deubiquitination of ubiquitin-specific

protease 7 (91). Both

ferritinophagy and TFR1 are considered key regulators of iron

accumulation (92). This iron is

released into the labile iron pool in the cytoplasm. During IR,

ferritinophagy induces intracellular iron overload, leading to

ferroptosis. Targeting ferritinophagy with inhibitors notably

decreases organ damage (93,94).

Furthermore, ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of TFR1

counteract abnormal iron accumulation and ferroptosis, mitigating

acute liver injury (95). During

ferroptosis, endocytosis of extracellular ferritin increases

Fe2+ levels in lysosomes. The release of free

Fe2+ from lysosomes accelerates ROS formation and

accumulation of lysosomal LPO. This generates 4-HNE and HNE

adducts, leading to lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Detection

of HNE adducts in the cytoplasm suggests that LPO diffuses from the

lysosome into the cytosol (96).

Numerous studies have highlighted the involvement of

cell death modalities in IRI, including apoptosis, necrosis,

necroptosis, autophagy, pyroptosis and ferroptosis (14–16,85,86).

A central focus of research is potential interactions between cell

death pathways and the identification of common upstream regulatory

mechanisms (101). Cells proceed

through different death pathways at distinct stages of IR. For

example, in cerebral ischemic stroke, brain tissue exhibits varying

patterns of cell death based on ischemic duration, oxygenation

levels and residual blood flow (96,97).

Moderate injury may activate autophagy as a protective mechanism to

preserve cell viability and facilitate recovery. By contrast,

severe injury typically leads to irreversible necrosis, apoptosis

and ferroptosis (102,103). ALDH2 is a key regulator of

cellular autophagy, apoptosis, necroptosis and ferroptosis during

IRI (7,20,37).

A growing body of evidence underscores the dynamic nature of cell

death processes in IRI and highlights the multifaceted role of

ALDH2 in regulating cell fate in various pathological contexts

(15,101–103). Further investigation into the

interplay between cell death pathways and ALDH2-mediated regulation

may unveil novel therapeutic strategies for mitigating IRI.

Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, is

characterized by morphological changes and is energy-dependent. In

the early stages, apoptosis is marked by cell shrinkage, chromatin

pyknosis (condensation), a reduction in cell volume and an increase

in cytoplasmic density, along with more compact organelles

(101,104). Pyknosis of chromatin, or the

condensation of nuclear material, is a hallmark of apoptosis.

Biochemically, apoptosis typically progresses through a

caspase-dependent cascade (101,104). Historically, apoptosis has been

considered to occur through two main pathways, the extrinsic (death

receptor-mediated) and the intrinsic (mitochondria-mediated)

pathway. Both pathways activate caspases, which initiate the

apoptotic process (101,105). The extrinsic pathway involves

interaction of cell surface death receptors [for example, Fas/CD95;

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-receptor (TRAIL-R);

TNF-receptor1 (TNFR1)] with their respective ligands, triggering

recruitment of proteins that activate caspases (101,105). By contrast, the intrinsic pathway

is driven by mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and loss

of mitochondrial integrity, a process regulated by the Bcl-2 family

of proteins. This pathway is characterized by balance between

pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax and anti-apoptotic proteins such

as Bcl-2. Following mitochondrial permeabilization, pro-apoptotic

factors, including cytochrome c, are released into cytosol,

leading to the formation of a caspase-activating complex (101,105). These apoptotic pathways have been

implicated in IRI, as studies have shown their involvement in organ

damage during ischemia and reperfusion (106,107). ALDH2 is a key regulator of

apoptosis in IRI in different organs. In a myocardial IRI model,

ALDH2 activation was shown to reduce the production of toxic

aldehydes such as 4-HNE and MDA, protecting the myocardium via the

ERK/p38 signaling pathway (3). In

a renal IRI model, ALDH2 activation attenuates inflammation and

decreases kidney injury by modulating the IκBα/NF-κB/IL-17C pathway

(4). Similarly, in the liver,

ALDH2 activation by Alda-1 induces autophagy via the AKT/mTOR and

AMPK pathways, thereby protecting the liver from IRI-induced

hepatocyte apoptosis (11).

Furthermore, the role of ALDH2 in apoptosis regulation extends to

the nervous system (15). In the

intrinsic apoptotic pathway, the AKT signaling pathway regulates

balance between pro-apoptotic Bax and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins

(108). In a pig heart IR model,

upregulation of ALDH2 increases Bcl-2/Bax ratio and decreases

activation of caspase-3 (109).

In humans, ALDH2 activation enhances mitochondrial membrane

potential via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, thereby decreasing ROS

production and inhibiting IR-induced apoptosis of cardiomyocytes

(18).

Cell death is typically classified into two

categories: RCD and accidental cell death (ACD). Apoptosis

represents RCD, while necrosis, driven by non-physiological stimuli

such as physical, mechanical or chemical stressors, typifies ACD

(110). Necrosis is characterized

by cell swelling, membrane rupture and release of cytoplasmic

contents. Necroptosis, a form of programmed necrosis, is primarily

regulated by post-translational modification of

receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIPK) 1, RIPK3 and mixed

lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) (111). The TNF signaling pathway is key

for necroptosis. Following TNF binding to TNFR1, a cascade leads to

the formation of complex I, which includes TNF-receptor-associated

death domain protein, TNF-receptor-associated factor 2, cellular

inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 or 2 and the linear ubiquitin

chain assembly complex. This complex facilitates linear

ubiquitination of receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein

kinase 1 at the K63 site, enabling recruitment of downstream

proteins (112). If complex I

formation is disrupted, TNF signaling activates complex IIa or IIb,

which comprise Fas-associated protein with death domain and

caspase-8, proteins that have key roles in apoptosis execution

(113). Other stimuli, including

death receptors such as Fas [CD95 or apoptosis-related protein

(Apo)-1], death receptor 3 (DR3) (Apo-3), DR4 (Apo-2 or TRAIL-R1),

DR5 (TRAIL-R2) and DR6, initiate necroptosis via RIPK3.

Additionally, pattern recognition receptors, including toll-like

receptor (TLR) 3 and TLR4, mediate necroptosis through the

formation of necroptotic bodies via toll/interleukin-receptor

(TRIF), IFN-β, RIPK3 and MLKL, especially in the presence of

caspase inhibitors (113).

The inhibition of ROS clearance and calcium overload

triggers necroptosis through inflammatory factors such as TNF-α.

RIP3, a key factor in necroptosis, can also drive inflammation and

ROS production (114,115). Necroptosis generally occurs

during the late reperfusion phase and can persist for an extended

period (34). In the early

reperfusion phase (within 10 min), inhibiting RIP3 does not

mitigate cardiac injury, suggesting that during the initial phase

of IRI, RIP3 primarily mediates damage through the regulation of

oxidative stress and mitochondrial function, rather than

necroptosis (116). Studies have

revealed that the necroptosis inhibitor necrostatin-1 provides

notable protection in the late stages of infarction, improving IR

organ function over time, however, its efficacy is limited when

administered early during infarction (117,118).

ALDH2 inhibits necroptosis primarily by eliminating

superoxide and reactive aldehydes, thereby maintaining

intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and stabilizing

mitochondrial function (119).

The protective effects of ALDH2 are mediated by several mechanisms:

ALDH2 downregulation activates caspase-associated pathways, which

subsequently promote necroptosis induction (120). Oxidative stress upregulates the

RIP1/RIP3/MLKL signaling cascade, leading to enhanced necroptosis.

In a glutamate-induced retinal excitotoxic model of glaucoma,

reduced ALDH2 expression is associated with increased expression of

RIP1/RIP3/MLKL signaling proteins, indicating elevated necroptosis

(121). In alcohol-induced

cardiac injury, decreased ALDH2 activity activates the caspase

pathway and necroptosis through RIP1/RIP3/MLKL signaling (122). Inhibition of ALDH2 activity leads

to the accumulation of 4-HNE, which promotes myocardial cell

necroptosis by inhibiting RIP1 ubiquitination and proteasomal

degradation. In mice, perfusion with 4-HNE exacerbates necroptosis

in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (123). Similarly, in high-glucose-induced

rats and cell necroptosis models, decreased ALDH2 expression is

associated with increased ROS production and upregulation of RIP1,

RIP3 and MLKL, resulting in enhanced necroptosis (7,124).

These findings highlight the key role of ALDH2 in mitigating

necroptosis via antioxidative and aldehyde detoxification

activities.

ALDH2 exhibits potent anti-inflammatory, anti-free

radical and anti-LPO activity, which intersect with ferroptosis

during IRI (39,98) (Fig.

5). ALDH2 serves a key role in mitigating ferroptosis by

metabolizing LPO products such as 4-HNE and MDA, thereby decreasing

oxidative stress-induced cellular damage. Additionally, ALDH2

enhances antioxidant defenses by activating SLC7A11, which promotes

intracellular GSH synthesis and decreases free iron

(Fe2+) levels, alleviating ferroptosis-mediated cell

injury (125). For example, in a

calcium oxalate kidney stone model, ALDH2 activation considerably

reduces renal crystal deposition and ferroptosis (125). In acute lung injury, ALDH2

provides protection by suppressing both pyroptosis and ferroptosis

(69). During post-cardiopulmonary

resuscitation organ damage, ALDH2 protects renal, intestinal and

pulmonary function by mitigating LPO and ferroptosis. Furthermore,

ALDH2 regulates the Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway to increase

cellular antioxidant capacity and diminish ferroptosis-associated

inflammatory damage. In periodontitis, ALDH2 activation alleviates

inflammation and promotes osteogenic differentiation of periodontal

ligament stem cells by inhibiting ferroptosis via Nrf2 activation

(126). Similarly, in gastric

ulcers, ALDH2 activation decreases inflammation and oxidative

stress while suppressing ferroptosis-associated damage via

inhibition of the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat

and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 inflammasome (127). Notably, ALDH2 deficiency or

decreased activity increases cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis

inducers or chemotherapeutic agents (128). In lung adenocarcinoma, decreased

ALDH2 expression increases sensitivity to platinum-based

chemotherapies by promoting ferroptosis (128).

Ferroptosis is driven by iron overload, free radical

generation, LPO and activation of cell death effectors, culminating

in membrane rupture. ALDH2 intervenes in multiple facets of ROS

clearance, inhibition of LPO and maintenance of mitochondrial

homeostasis during IR, all of which are associated with

ferroptosis. In IRI following cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ALDH2

effectively protects organ function by alleviating LPO and

ferroptosis in the kidney, intestine and lung (19,22).

ACSL4, a key enzyme in LPO associated with ferroptosis, is

regulated by ALDH2. In a murine model of Alzheimer's disease, ALDH2

suppresses special protein 1/ACSL4-mediated LPO and ferroptosis by

modulating downregulation of GPX4 and SLC7A11, while upregulating

NCOA4, thereby rescuing cardiac abnormality induced by amyloid

precursor protein/presenilin-1 mutations (129). During IR, LPO products such as

4-HNE and MDA serve as markers for ferroptosis. Specifically, 4-HNE

carbonylates cysteine residues at C93 of GPX4 and C247 of OTUD5,

hindering their interaction and aggravating K48-linked

polyubiquitin-related degradation of GPX4. ALDH2 activation

mitigates this effect, preserving GPX4 function and inhibiting

ferroptosis (35). ALDH2 also

stabilizes mitochondrial morphology and function, protecting

against cardiac dysfunction by activating the Nrf1-FUN14

domain-containing protein 1 (FUNDC1) cascade (130). Further mechanistic research

reveals that FUNDC1 interacts with GPX4 to facilitate its

recruitment into mitochondria via the translocase of the outer

membrane/translocase of the inner membrane (TIM) complex, enhancing

mitochondrial protection by ALDH2 (36). Regarding iron metabolism,

intracellular and extracellular ALDH2 decreases 4-HNE, activates

the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway to decrease intracellular iron accumulation

and mitigates hepatic cell ferroptosis through Parkin-mediated

mitochondrial autophagy (131).

Additionally, ALDH2 is associated with serum ferritin levels; ALDH2

mutant genotypes are associated with lower serum ferritin levels in

human males (132). These

findings underscore the multifaceted role of ALDH2 in modulating

ferroptosis and highlight its potential as a therapeutic target for

IRI.

Therapies targeting ALDH2 date from the late 1940s

with the introduction of disulfiram for the treatment of alcohol

addiction (30). Disulfiram

functions as a non-selective ALDH2 inhibitor, causing acetaldehyde

accumulation following alcohol consumption, which induces symptoms

such as nausea, vomiting and facial flushing (31). Despite early adoption of ALDH2

inhibitors such as disulfiram, to the best of our knowledge, no

clinically approved ALDH2 agonists exist for the treatment of IRI.

In IRI, ALDH2 expression is often decreased and its enzymatic

activity is impaired, leading to exacerbated tissue damage.

However, development of ALDH2 agonists offers promising potential

for the prevention and treatment of IRI. These agonists may restore

ALDH2 activity, mitigate oxidative stress and alleviate IR-induced

tissue injury (133–135). Research into ALDH2 agonists as

therapeutic agents for IRI is essential for identifying viable

treatment options in clinical practice. Determining the mechanisms

underlying ALDH2 activation and its protective effects against IRI

may facilitate development of novel compounds that target ALDH2

activation, paving the way for clinically applicable therapy.

The decreased activity of the ALDH2 2*2 variant

stems from a single amino acid substitution, where lysine replaces

glutamate, resulting in a 200-fold increase in the KM

(which represents the affinity of an enzyme for its substrate) for

NAD+ binding. Research has shown that Alda-1 does not

bind near the site of the ALDH2 2*2 mutation but rather closer to

the exit of the substrate-binding tunnel (135). Its binding site overlaps with

that of daidzin and extends toward the active site, leaving key

residues such as Cys302 and Glu268 unmodified, enabling them to

perform catalytic functions (135). The E487K substitution in ALDH2

2*2, where glutamate is replaced by lysine at position 487, leads

to decreased electron density near key residues, particularly those

involved in forming helix αG (residues 245–262) and the active-site

loop (residues 466–478). While Alda-1 does not interact directly

with these residues, it facilitates restoration of the α helix and

loop structures, bringing them closer to their native conformation

(135). By restricting substrate

diffusion within the substrate-to-coenzyme tunnel, Alda-1 increases

the effective concentration of reactive groups at the active site,

thereby enhancing dehydrogenase activity (135). This mechanism illustrates how

Alda-1 can restore enzymatic function in the ALDH2 2*2 variant,

presenting therapeutic potential for conditions associated with

ALDH2 dysfunction, such as IRI.

4-HNE serves as both a substrate for ALDH2 and an

inhibitor of its activity. ALDH2 contains a reactive Cys

nucleophile in its active site, which is modified by 4-HNE. This

lipid aldehyde forms covalent adducts by modifying protein thiols

and amines. At low micromolar concentrations, inhibition of ALDH2

by 4-HNE is reversible, but at higher concentrations, when the

active site thiols are covalently modified, inhibition becomes

irreversible (136). Alda-1 has

been shown to preserve ALDH2 catalytic activity in the presence of

high concentrations of 4-HNE, protecting the enzyme from

4-HNE-induced inactivation (26).

This protective effect is likely due to the ability of Alda-1 to

decrease interaction of 4-HNE with key residues such as Cys302,

Cys301 and Cys303, thereby preventing formation of aldehyde adducts

(26). This mechanism reveals how

Alda-1 maintains activity in structurally intact ALDH2,

distinguishing it from its effect on the ALDH2 2*2 variant.

GTN is used in clinical practice to treat

conditions such as angina pectoris, myocardial infarction and heart

failure (138). Its therapeutic

effects are primarily mediated by bioactivation of GTN in vascular

smooth muscle cells and platelets, leading to vasodilation of large

veins and arteries, inhibition of platelet aggregation and

increased levels of nitric oxide (NO) or S-nitrosothiol, as well as

elevated cyclic guanosine monophosphate levels (139). However, prolonged use of organic

nitrates such as GTN can result in development of nitrate

tolerance, characterized by increased oxidative stress, endothelial

dysfunction and sympathetic nerve activation (139,140). ALDH2 is the primary enzyme

responsible for bioactivating organic nitrates, catalyzing the

conversion of GTN to NO (141).

In human individuals with ALDH2-inactivating genotypes (ALDH2 1*2

and ALDH2 2*2) exhibit decreased bioactivation of GTN, which leads

to reduced vasodilatory effects (142). A clinical trial indicated that

ALDH2 gene polymorphisms affect the pharmacokinetics and

hemodynamics of GTN in human participants (143). In cardiovascular IRI, the

accumulation of free radicals exacerbates NO reactions with

superoxide, leading to the formation of peroxynitrite, which causes

nitration of ALDH2. This nitration impairs ALDH2 catalytic activity

and contributes to nitrate tolerance (144). Nitrates, including GTN, can

inhibit ALDH2 activity (139,140). In vitro, GTN rapidly and

effectively inactivates ALDH2 (145). Additionally, in vivo a

study in nitrate-tolerant rats revealed an association between

nitrate tolerance, ROS accumulation and loss of ALDH2 activity

(146). Therefore, when targeting

ALDH2 therapeutically, it is important to consider potential

antagonistic or competitive interactions with clinically used

drugs, such as nitrates. Strategies aimed at modulating ALDH2

activity should be evaluated to avoid unintended consequences, as

interventions that appear beneficial in one context may have

adverse effects in another.

ISO is a commonly used volatile anesthetic with a

well-established safety profile that exerts protective effects in

IRI across various types of organs. ISO therapy can mitigate

infarction volume and intracranial hemorrhage in tissue-type

plasminogen activator-exaggerated brain injury at low

concentrations (147). ISO may be

associated with a lower rate of postoperative myocardial infarction

and hemodynamic complications in patients undergoing coronary

artery bypass grafting (148).

Protective effects of ISO have also been observed in the heart

(149), kidney (150) and liver (151). The mechanism underlying

protective effects of ISO in IRI may involve the activation of

ALDH2. ISO pretreatment decreases mitochondrial translocation of

PKCδ and enhances ALDH2 phosphorylation (152). This leads to decreased release of

myocardial injury markers such as lactate dehydrogenase and

creatine kinase-myocardial band. Conversely, activation of PKCε

facilitates the protective effects of ISO (152). These findings suggest that ISO

exerts its protective effects in IRI through ALDH2 activation and

modulation of PKC signaling pathways, offering insight into

potential therapeutic strategies for mitigating tissue damage in

IRI.

IPC refers to the phenomenon where brief episodes

of ischemia before prolonged ischemic events confer cell protection

against subsequent IRI (39). To

the best of our knowledge, there are no effective clinical

interventions for established IRI; however, IPC has been studied as

a potential therapeutic strategy to mitigate tissue damage

associated with IRI (140–145).

In 1997, a clinical trial showed that IPC exerts functional

protection against simulated IRI (153); numerous trials have confirmed its

effectiveness in alleviating IRI in the heart, kidney, intestine

and liver (154–156). Genetic or pharmacological

inhibition of ALDH2 impairs the cardioprotective effects of IPC,

highlighting the role of ALDH2 activation in mediating protection

against IRI (157). The

protective mechanism of ALDH2 in IPC involves sequential activation

of PKCε and ALDH2 (158). PKCε

translocates into the mitochondria, where it interacts with ALDH2,

increasing its enzyme activity (159). This interaction is essential for

the protective effects of IPC against IRI. Overall, these findings

underscore the central role of ALDH2 activation in IPC-mediated

protection against IRI and offer insights into the mechanisms

involved. Further research into ALDH2 activation may facilitate

development of novel therapeutic strategies to prevent and treat

IRI.

Ethanol and acetaldehyde exposure are

pharmacological interventions that mimic the cardioprotective

effects of IPC, although the effects are limited at lower doses.

For example, brief exposure to ethanol (10–50 mM) before ischemia

has been shown to reduce myocardial damage caused by prolonged

ischemia (160). Cardioprotective

effects of ethanol are mediated by activation of ALDH2 (161). Similarly, pretreatment with 50 µM

acetaldehyde enhances ALDH2 activity and decreases myocardial

damage in wild-type mouse hearts, without considerably altering

cardiac acetaldehyde levels (157). However, in ALDH2 2*2 mice,

acetaldehyde pretreatment leads to a three-fold increase in cardiac

acetaldehyde levels, exacerbating IRI (157). The underlying mechanism of ALDH2

activation by ethanol and acetaldehyde involves activation of PKCε

in cardiomyocytes (157,160).

In addition to ethanol and acetaldehyde, other

compounds activate ALDH2, although the exact mechanisms remain

incompletely understood. Estrogen (162), heat shock factor 1 (163) and melatonin (164) have been proposed to increase

ALDH2 activity by promoting mitochondrial import of PKCε.

Antioxidants such as lipoic acid (130), resveratrol (165) and vitamins D (166), C (167) and E (168) activate ALDH2 through various

signaling pathways. Notably, flurbiprofen, a non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drug, activates ALDH2 in the context of its

anti-obesity effects (169). In

summary, pharmacological activation of ALDH2 offers potential

therapeutic avenues for IRI; further investigation into specific

drugs targeting ALDH2 activation is essential for minimizing side

effects and improving clinical outcomes.

ALDH activity is notably elevated in certain stem

or progenitor cells, designated ALDHbr cells. These cells have been

identified and isolated from numerous types of normal tissue,

including human cord blood, bone marrow, mobilized peripheral

blood, skeletal muscle and breast tissue, as well as rodent brain,

pancreas and prostate tissue, using flow cytometry techniques

(141,170). In a preclinical ischemic disease

model ALDHbr cell administration has considerable efficacy in

promoting tissue repair and local neovascularization and may have

clinical application (170). In

patients with ischemic heart failure, ALDHbr cell therapy is

considered safe, potentially enhancing perfusion and functional

recovery (171). Additionally,

clinical trials investigating intermittent claudication have

reported therapeutic effects consistent with ALDH2 isozyme

functions, such as improved ischemic tolerance, angiogenesis and

mitochondrial metabolism (172,173). However, the specific ALDH isozyme

targeted by these therapies is unclear. PCR array has demonstrated

a marked increase in ALDH2 expression in ALDHbr cells following

ischemic injury (174). By

contrast, a clinical trial involving patients with claudication and

infrainguinal peripheral artery disease, who received ten

injections of ALDHbr in the thigh and calf, showed no improvement

in peripheral artery disease outcomes, potentially due to sample

size limitations (173). While

ALDHbr cell therapy offers promising therapeutic potential, its

widespread application is constrained by its high cost and

complexity (173), with modest

effects on clinical outcome.

Targeting ferroptosis is a promising strategy for

mitigating IRI. Several small-molecule compounds designed to

intervene at various stages of the ferroptotic cascade have been

developed. Deferoxamine, a widely studied iron chelator, has

demonstrated considerable efficacy in inhibiting ferroptosis

(175–177). Deferoxamine decreases lactate

dehydrogenase release, highlighting its therapeutic potential in

alleviating tissue damage caused by IR in isolated wild-type mouse

hearts (175). In a randomized

controlled trial, deferoxamine effectively limited generation of

ROS by chelating redox−active iron, thereby alleviating

oxidative stress without reducing infarct size (176). Dexrazoxane, the only US Food and

Drug Administration-approved drug for doxorubicin-induced

cardiotoxicity, also serves as an iron chelator. In a murine model

of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy and IR, dexrazoxane decreases

non-heme iron levels in the heart and mitigates doxorubicin-induced

liver iron accumulation (177).

Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) has been identified as a potent inhibitor of

LPO (178). Li et al

(178) reported that Fer-1

decreases levels of pro-ferroptotic AA-PE, thereby preventing

cardiomyocyte death. Additionally, by inhibiting the TLR4/TRIF/type

I IFN signaling pathway associated with ferroptosis, Fer-1 impedes

neutrophil adhesion to coronary endothelial cells, thereby

mitigating inflammation (178).

Liproxstatin-1 is another selective ferroptosis inhibitor.

Administering Liproxstatin-1 1 h before ischemia in a mouse model

of intestinal IRI induces expression of GPX4 and decreases COX2

expression, as well as levels of 12- and 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic

acid, LPO products and serum markers such as lactate dehydrogenase,

TNF-α and IL-6 (179). Several

drugs target multiple stages of ferroptosis simultaneously. For

example, puerarin, used clinically for heart failure, exerts a

multifaceted protective effect against IRI. Liu et al

(180) showed that puerarin

decreases erastin-induced ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes by

downregulating NADPH oxidase 4 expression, upregulating GPX4 and

inhibiting both iron overload and LPO. In Alzheimer's disease, the

beneficial effects of puerarin are associated with changes in

expression of iron metabolism-associated proteins in neuronal

cells, including divalent metal ion transporter 1 and TFR1. By

mitigating iron metabolism-related damage, puerarin improves

cognitive function and memory in neurodegenerative disease

(181). Despite these advances,

no specific drug targeting ferroptosis has been developed for

treatment of IRI. Further research into the specific regulatory

mechanisms and targets of ferroptosis in IRI is essential for

identifying potential therapeutic strategies. Additionally,

upstream signaling pathways that regulate ferroptosis remain

unclear and the interaction between ALDH2 and ferroptosis, along

with the precise mechanisms involved, have yet to be fully

elucidated. Given the dynamic nature of pathological changes in

IRI, temporal progression of ferroptosis during IRI should be

further investigated. Potential therapies targeting ferroptosis are

summarized in Table II.

IRI is a complex complication in clinical practice,

where damage initiated during ischemia can persist and worsen upon

reperfusion. The mechanisms underlying IRI involve a number of

cellular injury processes, including autophagy, necrosis,

apoptosis, necroptosis and ferroptosis (101). Among the key factors in this

cascade, ALDH2 is a cellular oxidoreductase responsible for

acetaldehyde metabolism, which is associated with antioxidant

defense (28). The present review

highlights the key role of ALDH2 in IRI, particularly in scavenging

ROS and limiting LPO accumulation. Additionally, ALDH2 regulates

cell death pathways under oxidative stress conditions (7,20).

The interaction between ALDH2 and ferroptosis suggests these as

potential therapeutic targets for mitigating IRI. The present

review summarizes the role of ALDH2 in regulation of ferroptosis

and other cell death pathways, aiming to uncover intersections with

ferroptosis and enhance understanding of its role in IRI. However,

the mechanisms by which activators of ALDH2 and ferroptosis

inhibitors mitigate IRI remain incompletely understood. To the best

of our knowledge, clinical studies on the role of ALDH2 and

ferroptosis in IRI are scarce. Moreover, the aforementioned studies

research on these compounds has primarily been conducted in rodent

models of IR, highlighting the need for clinical trials to evaluate

their safety and efficacy. Future research should investigate the

detailed mechanisms through which ALDH2 and ferroptosis inhibitors

protect against IRI to develop more effective treatment strategies

and improve management and prevention of IRI in clinical

practice.

The authors would like to thank Dr Foquan Luo and

Dr Xiaomin Wu [Center for Rehabilitation Medicine, Department of

Anesthesiology, Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital (Affiliated

People's Hospital, Hangzhou Medical College)] for their assistance

in data collection.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

LH constructed figures and wrote the manuscript. WZ

conceived and designed the study and edited the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable. Both authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Panisello-Rosello A, Lopez A, Folch-Puy E,

Carbonell T, Rolo A, Palmeira C, Adam R, Net M and Roselló-Catafau

J: Role of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 in ischemia reperfusion injury:

An update. World J Gastroenterol. 24:2984–2994. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhang M, Liu Q, Meng H, Duan H, Liu X, Wu

J, Gao F, Wang S, Tan R and Yuan J: Ischemia-reperfusion injury:

Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 9:122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bai X, Zhang J, Yang H, Linghu K and Xu M:

SNHG3/miR-330-5p/HSD11B1 alleviates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion

injury by regulating the ERK/p38 signaling pathway. Protein Pept

Lett. 30:699–708. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chen Y, Xiong Y, Luo J, Hu Q, Lan J, Zou

Y, Ma Q, Yao H, Liu Z, Zhong Z, et al: Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2

protects the kidney from Ischemia-reperfusion injury by suppressing

the I κ B α/NF-κ B/IL-17C pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2023:22640302023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Diao M, Xu J, Wang J, Zhang M, Wu C, Hu X,

Zhu Y, Zhang M and Hu W: Alda-1, an activator of ALDH2, improves

postresuscitation cardiac and neurological outcomes by inhibiting

pyroptosis in swine. Neurochem Res. 47:1097–1099. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gao R, Lv C, Qu Y, Yang H, Hao C, Sun X,

Hu X, Yang Y and Tang Y: Remote ischemic conditioning mediates

cardio-protection after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by

reducing 4-HNE levels and regulating autophagy via the

ALDH2/SIRT3/HIF1alpha signaling pathway. J Cardiovasc Transl Res.

17:169–182. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kang P, Wang J, Fang D, Fang T, Yu Y,

Zhang W, Shen L, Li Z, Wang H, Ye H and Gao Q: Activation of ALDH2

attenuates high glucose induced rat cardiomyocyte fibrosis and

necroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 146:198–210. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Li M, Xu M, Li J, Chen L, Xu D, Tong Y,

Zhang J, Wu H, Kong X and Xia Q: Alda-1 ameliorates liver

Ischemia-Reperfusion injury by activating aldehyde dehydrogenase 2

and enhancing autophagy in mice. J Immunol Res. 2018:98071392018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lin D, Xiang T, Qiu Q, Leung J, Xu J, Zhou

W, Hu Q, Lan J, Liu Z, Zhong Z, et al: Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2

regulates autophagy via the Akt-mTOR pathway to mitigate renal

ischemia-reperfusion injury in hypothermic machine perfusion. Life

Sci. 253:1177052020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lin L, Tao JP, Li M, Peng J, Zhou C,

Ouyang J and Si YY: Mechanism of ALDH2 improves the neuronal damage

caused by hypoxia/reoxygenation. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

26:2712–2720. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Liu Z, Ye S, Zhong X, Wang W, Lai CH, Yang

W, Yue P, Luo J, Huang X, Zhong Z, et al: Pretreatment with the

ALDH2 activator Alda-1 protects rat livers from

ischemia/reperfusion injury by inducing autophagy. Mol Med Rep.

22:2373–2385. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ma LL, Ding ZW, Yin PP, Wu J, Hu K, Sun

AJ, Zou YZ and Ge JB: Hypertrophic preconditioning cardioprotection

after myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury involves

ALDH2-dependent metabolism modulation. Redox Biol. 43:1019602021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Pan G, Roy B and Palaniyandi SS: Diabetic

aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 Mutant (ALDH2*2) mice are more susceptible

to cardiac Ischemic-Reperfusion injury due to 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal

induced coronary endothelial cell damage. J Am Heart Assoc.

10:e0211402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Papatheodorou I, Galatou E, Panagiotidis

GD, Ravingerova T and Lazou A: Cardioprotective effects of

PPARbeta/delta activation against ischemia/reperfusion injury in

rat heart are associated with ALDH2 upregulation, amelioration of

oxidative stress and preservation of mitochondrial energy

production. Int J Mol Sci. 22:e0211402021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Qu Y, Liu Y and Zhang H: ALDH2 activation

attenuates oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation-induced cell

apoptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis and autophagy. Clin Transl

Oncol. 25:3203–1326. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sidramagowda Patil S, Hernandez-Cuervo H,

Fukumoto J, Krishnamurthy S, Lin M, Alleyn M, Breitzig M, Narala

VR, Soundararajan R, Lockey RF, et al: Alda-1 attenuates

hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury in mice. Front Pharmacol.

11:5979422020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sun X, Gao R, Li W, Zhao Y, Yang H, Chen

H, Jiang H, Dong Z, Hu J, Liu J, et al: Alda-1 treatment promotes

the therapeutic effect of mitochondrial transplantation for

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Bioact Mater. 6:2058–2069.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tan X, Chen YF, Zou SY, Wang WJ, Zhang NN,

Sun ZY, Xian W, Li XR, Tang B, Wang HJ, et al: ALDH2 attenuates

ischemia and reperfusion injury through regulation of mitochondrial

fusion and fission by PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in diabetic

cardiomyopathy. Free Radic Biol Med. 195:219–230. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wu H, Xu S, Diao M, Wang J, Zhang G and Xu

J: Alda-1 treatment alleviates lung injury after cardiac arrest and

resuscitation in swine. Shock. 58:464–469. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Xu T, Guo J, Wei M, Wang J, Yang K, Pan C,

Pang J, Xue L, Yuan Q, Xue M, et al: Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2

protects against acute kidney injury by regulating autophagy via

the Beclin-1 pathway. JCI Insight. 6:e1381832021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yoval-Sanchez B, Calleja LF, de la Luz

Hernandez-Esquivel M and Rodriguez-Zavala JS: Piperlonguminine a

new mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase activator protects the

heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen

Subj. 1864:1296842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yu Q, Gao J, Shao X, Lu W, Chen L and Jin

L: The Effects of Alda-1 treatment on renal and intestinal injuries

after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in pigs. Front Med (Lausanne).

9:8924722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang R, Xue MY, Liu BS, Wang WJ, Fan XH,

Zheng BY, Yuan QH, Xu F, Wang JL and Chen YG: Aldehyde

dehydrogenase 2 preserves mitochondrial morphology and attenuates

hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocyte injury. World J Emerg

Med. 11:246–254. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang ZX, Li H, He JS, Chu HJ, Zhang XT

and Yin L: Remote ischemic postconditioning alleviates myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury by up-regulating ALDH2. Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 22:6475–6484. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhou T, Wang X, Wang K, Lin Y, Meng Z, Lan

Q, Jiang Z, Chen J, Lin Y, Liu X, et al: Activation of aldehyde

dehydrogenase-2 improves ischemic random skin flap survival in

rats. Front Immunol. 14:11276102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen CH, Ferreira JC, Gross ER and

Mochly-Rosen D: Targeting aldehyde dehydrogenase 2: New therapeutic

opportunities. Physiol Rev. 94:1–34. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lamb RJ, Griffiths K, Lip GYH, Sorokin V,

Frenneaux MP, Feelisch M and Madhani M: ALDH2 polymorphism and

myocardial infarction: From alcohol metabolism to redox regulation.

Pharmacol Ther. 259:1086662024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yoshida A, Hsu LC and Yasunami M: Genetics

of human alcohol-metabolizing enzymes. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol

Biol. 40:255–287. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mali VR and Palaniyandi SS: Regulation and

therapeutic strategies of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal metabolism in heart

disease. Free Radic Res. 48:251–263. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Schneider C, Porter NA and Brash AR:

Routes to 4-hydroxynonenal: Fundamental issues in the mechanisms of

lipid peroxidation. J Biol Chem. 283:15539–15543. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kimura M, Yokoyama A and Higuchi S:

Aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 as a therapeutic target. Expert Opin Ther

Targets. 23:955–966. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ke K, Li L, Lu C, Zhu Q, Wang Y, Mou Y,

Wang H and Jin W: The crosstalk effect between ferrous and other

ions metabolism in ferroptosis for therapy of cancer. Front Oncol.

12:9160822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fang X, Ardehali H, Min J and Wang F: The

molecular and metabolic landscape of iron and ferroptosis in

cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 20:7–23. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Xiang Q, Yi X, Zhu XH, Wei X and Jiang DS:

Regulated cell death in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Trends Endocrinol Metab. 35:219–234. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu L, Pang J, Qin D, Li R, Zou D, Chi K,

Wu W, Rui H, Yu H, Zhu W, et al: Deubiquitinase OTUD5 as a novel

protector against 4-HNE-triggered ferroptosis in myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e23018522023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Bi Y, Liu S, Qin X, Abudureyimu M, Wang L,

Zou R, Ajoolabady A, Zhang W, Peng H, Ren J and Zhang Y: FUNDC1

interacts with GPx4 to govern hepatic ferroptosis and fibrotic

injury through a mitophagy-dependent manner. J Adv Res. 55:45–60.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhu W, Feng D, Shi X, Wei Q and Yang L:

The potential role of mitochondrial acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 in

urological cancers from the perspective of ferroptosis and cellular

senescence. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:8501452022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Droge W: Free radicals in the

physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 82:47–95.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chen CH, Sun L and Mochly-Rosen D:

Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase and cardiac diseases.

Cardiovasc Res. 88:51–57. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wilson DF and Matschinsky FM: Ethanol

metabolism: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Med Hypotheses.

140:1096382020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Hink U, Daiber A, Kayhan N, Trischler J,

Kraatz C, Oelze M, Mollnau H, Wenzel P, Vahl CF, Ho KK, et al:

Oxidative inhibition of the mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase

promotes nitroglycerin tolerance in human blood vessels. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 50:2226–2232. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Xu Y, Yuan Q, Cao S, Cui S, Xue L, Song X,

Li Z, Xu R, Yuan Q and Li R: Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 inhibited

oxidized LDL-induced NLRP3 inflammasome priming and activation via

attenuating oxidative stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

529:998–1004. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Moldovan L and Moldovan NI: Oxygen free

radicals and redox biology of organelles. Histochem Cell Biol.

122:395–412. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Bielski BH, Arudi RL and Sutherland MW: A

study of the reactivity of HO2/O2-with unsaturated fatty acids. J

Biol Chem. 258:4759–4761. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Browne RW and Armstrong D: HPLC analysis

of lipid-derived polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation products

in oxidatively modified human plasma. Clin Chem. 46:829–836. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Schneider C, Boeglin WE, Yin H, Porter NA

and Brash AR: Intermolecular peroxyl radical reactions during

autoxidation of hydroxy and hydroperoxy arachidonic acids generate

a novel series of epoxidized products. Chem Res Toxicol.

21:895–903. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Singh S, Brocker C, Koppaka V, Chen Y,

Jackson BC, Matsumoto A, Thompson DC and Vasiliou V: Aldehyde

dehydrogenases in cellular responses to oxidative/electrophilic

stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 56:89–101. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Gao J, Hao Y, Piao X and Gu X: Aldehyde

dehydrogenase 2 as a therapeutic target in oxidative stress-related

diseases: Post-translational modifications deserve more attention.

Int J Mol Sci. 23:26822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Breitzig M, Bhimineni C, Lockey R and

Kolliputi N: 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal: A critical target in oxidative

stress? Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 311:C537–C543. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Schaur RJ, Siems W, Bresgen N and Eckl PM:

4-Hydroxy-nonenal-a bioactive lipid peroxidation product.

Biomolecules. 5:2247–337. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Forman HJ: Reactive oxygen species and

alpha, beta-unsaturated aldehydes as second messengers in signal

transduction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1203:35–44. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Shoeb M, Ansari NH, Srivastava SK and

Ramana KV: 4-Hydroxynonenal in the pathogenesis and progression of

human diseases. Curr Med Chem. 21:230–237. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhang H and Forman HJ: Signaling pathways

involved in phase II gene induction by alpha, beta-unsaturated

aldehydes. Toxicol Ind Health. 25:269–278. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Dalleau S, Baradat M, Gueraud F and Huc L:

Cell death and diseases related to oxidative stress:

4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) in the balance. Cell Death Differ.

20:1615–1630. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Xue Z, Zhao K, Sun Z, Wu C, Yu B, Kong D

and Xu B: Isorhapontigenin ameliorates cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion injury via modulating Kinase

Cepsilon/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Brain Behav. 11:e021432021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wang Y, Li B, Liu G, Han Q, Diao Y and Liu

J: Corilagin attenuates intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in

mice by inhibiting ferritinophagy-mediated ferroptosis through

disrupting NCOA4-ferritin interaction. Life Sci. 334:1221762023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Endo J, Sano M, Katayama T, Hishiki T,

Shinmura K, Morizane S, Matsuhashi T, Katsumata Y, Zhang Y, Ito H,

et al: Metabolic remodeling induced by mitochondrial aldehyde

stress stimulates tolerance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circ

Res. 105:1118–1127. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ and Zollner H:

Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and

related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 11:81–128. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Giera M, Lingeman H and Niessen WM: Recent

advancements in the LC- and GC-Based analysis of malondialdehyde

(MDA): A brief overview. Chromatographia. 75:433–440. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Esterbauer H and Zollner H: Methods for

determination of aldehydic lipid peroxidation products. Free Radic

Biol Med. 7:197–203. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Shen Z, Zhang Y, Bu G and Fang L: Renal

denervation improves mitochondrial oxidative stress and cardiac

hypertrophy through inactivating SP1/BACH1-PACS2 signaling. Int

Immunopharmacol. 141:1127782024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Tsikas D: Assessment of lipid peroxidation

by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological

samples: Analytical and biological challenges. Anal Biochem.

524:13–30. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Lankin VZ, Tikhaze AK and Melkumyants AM:

Malondialdehyde as an important key factor of molecular mechanisms

of vascular wall damage under heart diseases development. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:1282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Busch CJ and Binder CJ: Malondialdehyde

epitopes as mediators of sterile inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta

Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 1862:398–406. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Agadjanyan ZS, Dmitriev LF and Dugin SF: A

new role of phosphoglucose isomerase. Involvement of the glycolytic

enzyme in aldehyde metabolism. Biochemistry (Mosc). 70:1251–1255.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Liu H, Wu X, Luo J, Wang X, Guo H, Feng D,

Zhao L, Bai H, Song M, Liu X, et al: Pterostilbene attenuates

astrocytic inflammation and neuronal oxidative injury after

Ischemia-reperfusion by inhibiting NF-κB phosphorylation. Front

Immunol. 10:24082019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Qi D, Chen P, Bao H, Zhang L, Sun K, Song

S and Li T: Dimethyl fumarate protects against hepatic

ischemia-reperfusion injury by alleviating ferroptosis via the

NRF2/SLC7A11/HO-1 axis. Cell Cycle. 22:818–828. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Wang IC, Lin JH, Lee WS, Liu CH, Lin TY

and Yang KT: Baicalein and luteolin inhibit

ischemia/reperfusion-induced ferroptosis in rat cardiomyocytes. Int

J Cardiol. 375:74–86. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Cao Z, Qin H, Huang Y, Zhao Y, Chen Z, Hu

J and Gao Q: Crosstalk of pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and

mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2-related mechanisms in

sepsis-induced lung injury in a mouse model. Bioengineered.

13:4810–4820. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Yoval-Sanchez B and Rodriguez-Zavala JS:

Differences in susceptibility to inactivation of human aldehyde

dehydrogenases by lipid peroxidation byproducts. Chem Res Toxicol.

25:722–729. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zhang T, Zhao Q, Ye F, Huang CY, Chen WM

and Huang WQ: Alda-1, an ALDH2 activator, protects against hepatic

ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats via inhibition of oxidative

stress. Free Radic Res. 52:629–638. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Ma XH, Liu JH, Liu CY, Sun WY, Duan WJ,

Wang G, Kurihara H, He RR, Li YF, Chen Y, et al: ALOX15-launched

PUFA-phospholipids peroxidation increases the susceptibility of

ferroptosis in ischemia-induced myocardial damage. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7:2882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Yan HF, Tuo QZ, Yin QZ and Lei P: The

pathological role of ferroptosis in ischemia/reperfusion-related

injury. Zool Res. 41:220–230. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Wu X, Li Y, Zhang S and Zhou X:

Ferroptosis as a novel therapeutic target for cardiovascular

disease. Theranostics. 11:3052–3059. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S,

Croix CS, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyurin VA, Ritov VB, et al: Oxidized

arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem

Biol. 13:81–90. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Liu J, Kang R and Tang D: Signaling

pathways and defense mechanisms of ferroptosis. FEBS J.

289:7038–7050. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Liu C, Li Z, Li B, Liu W, Zhang S, Qiu K

and Zhu W: Relationship between ferroptosis and mitophagy in

cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury: A mini-review. PeerJ.

11:e149522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Liang C, Zhang X, Yang M and Dong X:

Recent progress in ferroptosis inducers for cancer therapy. Adv

Mater. 31:e19041972019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M,

Shchepinov MS and Stockwell BR: Peroxidation of polyunsaturated

fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 113:E4966–E49675. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Haeggstrom JZ and Funk CD: Lipoxygenase

and leukotriene pathways: Biochemistry, biology, and roles in

disease. Chem Rev. 111:5866–5898. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Braughler JM, Duncan LA and Chase RL: The

involvement of iron in lipid peroxidation. Importance of ferric to

ferrous ratios in initiation. J Biol Chem. 261:10282–10289. 1986.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Matsuyama M, Nakatani T, Hase T, Kawahito

Y, Sano H, Kawamura M and Yoshimura R: The expression of

cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases in renal ischemia-reperfusion

injury. Transplant Proc. 36:1939–1942. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Jiang M, Jike Y, Liu K, Gan F, Zhang K,

Xie M, Zhang J, Chen C, Zou X, Jiang X, et al: Exosome-mediated

miR-144-3p promotes ferroptosis to inhibit osteosarcoma

proliferation, migration, and invasion through regulating ZEB1. Mol

Cancer. 22:1132023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Yang R, Gao W, Wang Z, Jian H, Peng L, Yu

X, Xue P, Peng W, Li K and Zeng P: Polyphyllin I induced

ferroptosis to suppress the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma

through activation of the mitochondrial dysfunction via

Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 axis. Phytomedicine. 122:1551352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Chen X, Huang J, Yu C, Liu J, Gao W, Li J,

Song X, Zhou Z, Li C, Xie Y, et al: A noncanonical function of

EIF4E limits ALDH1B1 activity and increases susceptibility to

ferroptosis. Nat Commun. 13:63182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Jang EJ, Jeong HO, Park D, Kim DH, Choi

YJ, Chung KW, Park MH, Yu BP and Chung HY: Src Tyrosine kinase

activation by 4-hydroxynonenal upregulates p38, ERK/AP-1 signaling

and COX-2 expression in YPEN-1 Cells. PLoS One. 10:e01292442015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|