Introduction

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are the most common

tumors of infancy and childhood, with an incidence of 2–3% in the

neonate, 10% in the baby after 1 year and up to 23% in premature

infants, with a slight female predominance (1). Hemangiomas are characterized

pathologically by endothelial cell hyperproliferation and may be

divided into the following three types, according to the depth of

their locations: Superficial hemangioma located in the papillary

dermis, deep hemangioma located in the reticular dermis and

subcutaneous tissue, and mixed hemangioma, which is a mixture of

superficial and deep components (2).

Deep hemangiomas present as blue or colorless masses, whereas

superficial hemangiomas often present as bright red lesions

(2). Blood flow in hemangiomas can be

observed by ultrasonography. The disease is self-limiting, which

often occurs in the neonatal period, and then enters the

proliferative phase, stops development around the age of 1 and

begins to regress (3,4). Parotid hemangioma is the most common

type of salivary gland hemangioma in children. Complications of

this condition may include ulceration, life-threatening airway

obstruction and the risk of delayed language acquisition due to ear

involvement. Patients should therefore be treated as soon a

possible (5). A number of clinical

studies have shown that propranolol is usually highly effective for

deep hemangiomas and that timolol maleate is usually highly

effective for superficial lesions (6). The present study reports the application

of topical timolol maleate combined with oral propranolol for

parotid IHs in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

(Hospital of Stomatology, China Medical University, Shenyang,

Liaoning, China), resulting in a clear curative effect.

Patients and methods

Patients

In total, 22 patients with mixed-type parotid gland

proliferating hemangioma were treated with topical timolol maleate

combined with oral propranolol between October 2012 and April 2014

at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in the Hospital

of Stomatology (Table I). The group

consisted of 9 boys and 13 girls, with a mean age of 4.7 months

(range, 2–9 months). The volume of these tumors varied between

3.5×4×0.5 and 7×8×3 cm, as measured by Doppler ultrasonography

(Philips iU22 Cart F 4D ultrasound system; Philips Electronics

Japan, Ltd., Tokyo Japan). The diagnosis of hemangioma was made

based on the medical history (age of onset), clinical presentations

and Doppler ultrasonography: A mixture of superficial and deep

components were observed and blood flow in the hemangiomas was

identified by ultrasonography. Data was collected from patient

files, including clinical characteristics, efficacy of treatment

and adverse reactions. The inclusion criteria for this study were

as follows: i) No infants were administered any treatment prior to

propranolol and timolol maleate.; ii) any other vascular

malformations were excluded, according to the classification and

nomenclature of vascular anomalies proposed by Waner and Suen

(7); and iii) normal chest X-ray,

electrocardiogram, blood coagulation, liver function, renal

function and blood routine examination results. The Ethical Review

Board of China Medical University approved the study and the

parents of all infants provided written informed consent for

publication.

| Table I.Summary of treatment of IHs with

topical timolol maleate combined with oral propranolol. |

Table I.

Summary of treatment of IHs with

topical timolol maleate combined with oral propranolol.

| Patient no. | Gender | Age at treatment

onset, months | Treatment duration,

weeks | Size of IH prior to

treatment, cma | Size of IH after

treatment, cma | Side effects | Follow-up,

months | Response |

|---|

| 1 | F | 3 | 20 | 2.5/2/0.5 | 0/0/0 | None | 6 | Excellent |

| 2 | M | 3 | 24 | 8/7/3 | 0/0/0 | None | 6 | Excellent |

| 3 | M | 2 | 24 | 4/3.5/1 | 0/0/0 | None | 10 | Excellent |

| 4 | F | 3 | 16 | 3.5/3/0.5 | 1/1.5/0 | None | 9 | Good |

| 5 | M | 7 | 16 | 3/4/1.5 | 1/0.5/0 | Diarrhea | 8 | Good |

| 6 | F | 6 | 28 | 7/6.5/2 | 0/0/0.5 | None | 10 | Excellent |

| 7 | F | 2.5 | 12 | 1.5/1/0.5 | 0.5/0/0 | None | 12 | Excellent |

| 8 | F | 8 | 20 | 3.5/2/1 | 2/1/0.5 | None | 6 | Good |

| 9 | M | 5 | 24 | 4.5/3.5/1.5 | 3/2/0.5 | None | 10 | Moderate |

| 10 | F | 6 | 16 | 5/3.5/2.5 | 1/1.5/1 | None | 8 | Excellent |

| 11 | F | 2.5 | 32 | 8/7/3 | 2/1.5/1 | None | 10 | Excellent |

| 12 | M | 3 | 12 | 2/3/0.5 | 1/0.5/0 | None | 9 | Excellent |

| 13 | M | 2 | 32 | 7/6.5/2 | 0/0/0 | None | 8 | Excellent |

| 14 | F | 4 | 28 | 5/4/1 | 1/0.5/0.5 | None | 6 | Excellent |

| 15 | M | 6 | 20 | 3/3/0.5 | 1/1.5/0 | None | 6 | Good |

| 16 | F | 9 | 24 | 4/4/2 | 1/0.5/1 | None | 8 | Excellent |

| 17 | F | 7 | 24 | 5/5/2 | 2/2/0.5 | None | 12 | Good |

| 18 | M | 5 | 12 | 2.5/2.5/0.5 | 1/0.5/0 | None | 12 | Excellent |

| 19 | M | 3 | 16 | 2/2/0.5 | 0/0/0 | None | 9 | Excellent |

| 20 | F | 4.5 | 20 | 2.5/1.5/1 | 0/0/0 | None | 8 | Excellent |

| 21 | F | 3.5 | 16 | 2/1.5/0.5 | 0.5/0.5/0 | None | 6 | Good |

| 22 | F | 9 | 28 | 4/4.5/2 | 2/2/0.5 | None | 7 | Moderate |

Treatment protocol

All patients were admitted to the hospital when the

hemangiomas were in the rapidly proliferating phase. Propranolol

(10 mg/tablet; Tianjin Lisheng Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tianjin,

China) was prepared from a tablet into a suitable solution at a

single oral dose of 1.0–1.5 mg/kg/day (1.0 mg/kg for patients <3

months old and 1.5 mg/kg for patients >3 months old). A small

amount of 0.5% timolol maleate eye drop solution (25 mg/5 ml; Wuhan

Five King Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei, China) was also

topically applied with medical cotton swabs to the area of the

lesion twice a day, every 12 h. For the first 3–5 days of

management, heart rate, blood pressure and blood glucose levels

were monitored in the inpatient ward. The patients who experienced

no adverse reactions were topically administered the drug by their

parents or guardians following discharge from the hospital. Close

observation was paid to the heart rate, blood pressure and other

vital signs during the treatment, and the parents were informed to

look for local redness and symptoms such as a loss of appetite,

nausea, vomiting, wheezing, shortness of breath or lethargy. Once

any symptom appeared, the drugs were stopped immediately and the

patient observed carefully. The patients were reexamined

periodically in order to observe the size and color of the

hemangiomas for assessment of the curative effect. The dose of the

drug was altered according to the change in the weight of the

patient and the degree of adverse reaction at the period of

follow-up. Treatment was continued until 1 year old, unless

complete resolution occurred (8). The

follow-up timeline ranged from 1–10 months (median, 6.4

months).

Evaluation of efficacy

The therapeutic outcome was evaluated by Doppler

ultrasonography. The results were measured by the hemisphere

measurement and visual changes on photography (9). The clinical effect of treatment was

graded on a 4-point scale proposed by Achauer et al

(10), based on improvements in tumor

volume, color and texture after treatment, as follows: I (poor),

tumor volume decreased by <25%; II (moderate), tumor volume

decreased by 26–50%; III (good), tumor volume decreased by 51–75%;

and IV (excellent), tumor volume decreased by 76–100%.

With regard to safety, heart rate, systolic blood

pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and blood glucose

level were close monitored in the course of the 3-day

hospitalization period and were recorded 1 h after each dose. Local

side effects, including rashes, red spots, erosion and ulceration,

were also closely observed.

Statistical analysis

All data was entered into a database and processed

using SPSS software (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the differences in the

average heart rate, SBP and DBP prior to and following drug

administration. P<0.05 was used to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

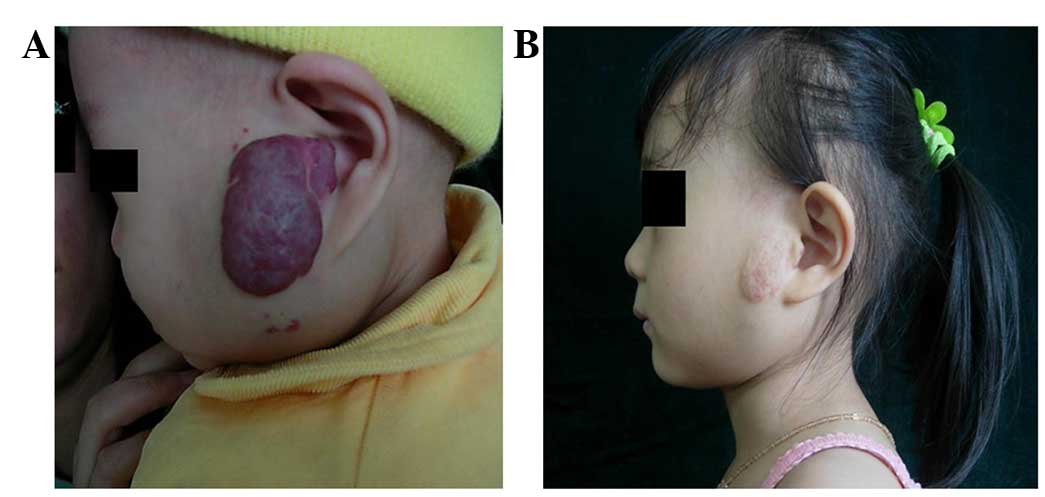

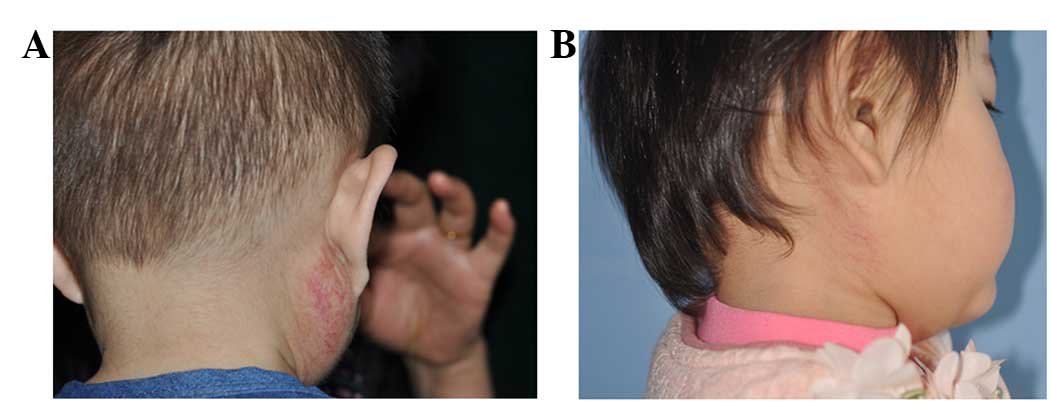

All the hemangiomas decreased in size following

treatment and in the majority of cases, the tumor color changed

from bright red to dull red. Efficacy scores was evaluated as

follows: IV (excellent), 14 cases (64%); III (good), 6 cases (27%);

II (moderate), 2 cases (9%); and I (poor), 0 cases (0%). The

parents were quite satisfied with the results. At 24 h

post-medication, the tension of the tumor surface of the majority

of children decreased and the texture became softer. In total, the

drug was administered for 12 weeks in 3 patients, for 16 weeks in 5

patients, for 20 weeks in 4 patients, for 24 weeks in 5 patients,

for 28 weeks in 3 patients and for 32 weeks in 2 patients, with a

mean time of 21.1 weeks. The tumor of 1 patient regressed

completely following 16 weeks of treatment. However, the tumor had

relapsed when the infant was followed up 6 weeks later and the

proliferation was subsequently effectively controlled by the

continuation of medication for ~10 weeks after treatment, until it

decreased in size. Typical cases are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

No infants were withdrawn from the treatment study

due to side effects. In total, 22 infants exhibited a decreased

heart rate, blood pressure and rate of breathing after starting the

treatment. However, all these signs returned to normal after

propranolol had been administered for >12 h (P>0.05; Table II), and no patients required

additional treatment. No severe gastrointestinal adverse reactions

occurred.

| Table II.Heart rate and blood pressure at

baseline and during the propranolol and timolol maleate treatment

initiation period (mean ± standard deviation). |

Table II.

Heart rate and blood pressure at

baseline and during the propranolol and timolol maleate treatment

initiation period (mean ± standard deviation).

| Parameter | Baseline | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|

| Heart rate (beats

per min) | 127.1±11.5 | 124.0±15.6 | 124.3±13.4 | 125.3±14.8 |

| SBP (mmHg) |

85.4±13.3 |

84.6±17.1 |

85.5±16.6 |

85.0±18.2 |

| DBP (mmHg) |

57.5±10.2 |

58.3±12.6 |

57.1±11.2 | 56.9±9.7 |

Discussion

Infantile parotid proliferating hemangiomas, which

are the most common parotid tumors, occurred around 1 year after

birth, accounting for >50% parotid gland tumors in infants

(11). Hemorrhage, ulceration,

infection and external auditory canal compression are the main

complications of the tumor. Facial hemangiomas can cause serious

psychological issues in the affected patients. Positive

intervention rather than observation should be therefore be

adopted, and appropriate treatment should be provided according to

the different growth phases of the hemangiomas (12).

At present, the treatment methods for IH are

conservative rather than surgical, and include as drug and laser

therapies. Common drugs for the treatment of hemangioma are

corticosteroids, and anticancer drugs, such as interferon and

imiquimod (13–18), but these methods lead to different

degrees of side effects. The only suitable treatment for early

superficial hemangiomas is laser therapy (19). With regard to the surgical treatment

of parotid region hemangiomas, there have been various proposals

and the optimal surgical duration is uncertain. The surgical

treatment must be selected carefully due to complications such as

temporary paralysis, recurrence, salivary fistula, hematoma,

auriculotemporal nerve syndrome, facial nerve injury and scarring

(20).

Hemangiomas can be divided into three types

according to the depth of their locations: Superficial hemangioma

located in the papillary dermis, deep hemangioma located in the

reticular dermis and subcutaneous tissue, and mixed hemangioma,

which is a mixture of superficial and deep components (21). In the Department of Oral and

Maxillofacial Surgery in the Hospital of Stomatology, personalized

treatment options are used based on the hemangioma site, size and

depth, among other factors, in order to obtain the best treatment

effect (22). Currently, drug

treatment is the preferred treatment of IHs. In 2008,

Léauté-Labrèze et al first reported the use propranolol for

the treatment of IH, and achieved good results (22). This study soon attracted the attention

of scholars from all over the world, which triggered a series of

associated studies on propranolol in the treatment of IH (8,11,22,23).

Propranolol is a non-selective β-adrenergic antagonist, whose

treatment effect on IH is verified. Compared with the traditional

corticosteroid therapy, it has better tolerability, less adverse

reactions and greater efficiency (23–25).

Timolol maleate is a non-selective potent β-adrenergic antagonist

(β1 and β2) that has been mainly used for the clinical treatment of

hypertension, angina pectoris, tachycardia and glaucoma (26). The predominant adverse effects include

hypotension, hypoglycemia, bronchospasm and local pruritus. Timolol

was first used for glaucoma in the United States in 1978. It is

safe for the treatment of the pediatric population, and has been

used for glaucoma as a first-line medicine by pediatric

ophthalmologists for >30 years (27). Timolol, as a type of ophthalmic drug,

causes little irritation to local tissues, and its effect can only

be observed in certain regions, with little systemic reaction, so

the application of timolol maleate as a topical medication is

extremely safe (28). Numerous

clinical studies have demonstrated that treatment with propranolol

is effective for both deep and superficial hemangiomas. In

addition, the treatment response to oral propranolol is better for

deep IHs than superficial IHs. Generally, timolol meleate is a

highly effective treatment for superficial lesions. Therefore,

combined treatment with oral propranolol and topical timolol

maleate has been developed for mixed and superficial lesions, and

oral propranolol is used to treat deep lesions (29).

No uniform safe dosage standard exists for the

treatment of hemangioma using propranolol, however, according to

domestic studies (30–33) and our considerable clinical

experience, we believe that 1.0 mg/kg propranolol for patients

<3 months old and 1.5 mg/kg propranolol for patients >3

months old is a safe dosage. An infant should, however, undergo a

detailed general examination prior to this prescription.

Furthermore, all infants should be hospitalized as an inpatient

under observation for 3–5 days after the initial treatment, and the

blood pressure, heart rate and adverse reactions should be closely

monitored.

In 2010, Guo and Ni (34) described the case of a 4-month-old

infant with superficial capillary hemangioma of the eyelid, and

became the first study to report a successful outcome subsequent to

the use of timolol solution; this success was subsequently

reinforced by a series of other studies. In 2011, Pope and

Chakkittakandiyil reported 6 cases of IHs treated with timolol in

which the symptoms improved significantly (35). Li et al reported 25 cases of

children with hemangiomas who were administered 0.5% topical

timolol maleate, resulting in a clear positive effect. According to

the related literature, the pharmacological effects of timolol are

8 times higher than propranolol (36). Therefore, the oral dose of propranolol

can be reduced while topically using timolol maleate, therefore

ensuring drug safety and reducing complications.

Despite the strong effects of propranolol and

timolol maleate for the treatment of IH, the mechanism of action

remains unknown (37).

Vasoconstriction may be responsible for the early effects on the

color of the hemangioma due to the decreased release of nitric

oxide. Growth arrest is attributable to the blocking of

proangiogenic signals, including vascular endothelial growth

factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, matrix metalloproteinases

and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (38).

In the present study, attention was focused on the

use of topical timolol maleate combined with oral propranolol for

the treatment of parotid IHs. Good results were achieved using this

combined treatment, which resulted in clear curative effects, with

reduced complications. On the whole, as a quicker, safe and

effective treatment, combined treatment with topical timolol

maleate and oral propranolol for the treatment of parotid IHs

should become the preferred therapeutic option.

References

|

1

|

Phung TL, Hochman M and Mihm MC: Current

knowledge of the pathogenesis of infantile hemangiomas. Arch Facial

Plast Surg. 7:319–321. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yuan WL, Jin ZL, Wei JJ, Liu ZY, Xue L and

Wang XK: Propranolol given orally for proliferating infantile

haemangiomas: Analysis of efficacy and serological changes in

vascular endothelial growth factor and endothelial nitric oxide

synthase in 35 patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 51:656–661.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Mulliken JB and Glowacki J: Hemangiomas

and vascular malformations in infants and children: A

classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 69:412–422. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Buckmiller LM, Richter GT and Suen JY:

Diagnosis and management of hemangiomas and vascular malformations

of the head and neck. Oral Dis. 16:405–418. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Enjolras O and Gelbert F: Superficial

hemangiomas: Associations and management. Pediatr Dermatol.

14:173–179. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu X, Tai M, Qin Z, Li K and Ge C:

Clinical analysis for treatment of 1,080 cases of infantile

hemangiomas with oral propranolol. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi.

94:1878–1881. 2014.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Waner M and Suen JY: Management of

congenital vascular lesions of the head and neck. Oncology

(Williston Park). 9:989–994, 997; discussion 998 passim.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Malik MA, Menon P, Rao KL and Samujh R:

Effect of propranolol vs prednisolone vs. propranolol with

prednisolone in the management of infantile hemangioma: A

randomized controlled study. J Pediatr Surg. 48:2453–2459. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E,

Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, Horii KA, Lucky AW, Mancini AJ, Metry DW,

Newell B, et al: Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas:

Clinical characteristics predicting complications and treatment.

Pediatrics. 118:882–887. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Achauer BM, Chang CJ and Vander Kam VM:

Management of hemangioma of infancy: Review of 245 patients. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 99:1301–1308. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mantadakis E, Tsouvala E, Deftereos S,

Danielides V and Chatzimichael A: Involution of a large parotid

hemangioma with oral propranolol: An illustrative report and review

of the literature. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012:3538122012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zheng JW: Infantile hemangiomas: Seldom

wait and see. China Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.

10:163–164. 2012.(In Chinese).

|

|

13

|

Bennett ML, Fleischer AB Jr, Chamlin SL

and Frieden IJ: Oral corticosteroid use is effective for cutaneous

hemangiomas: An evidence-based evaluation. Arch Dermatol.

137:1208–1213. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gangopadhyay AN, Sharma SP, Gopal SC,

Gupta DK, Panjawani K and Sinha JK: Local steroid therapy in

cutaneous hemangiomas. Indian Pediatr. 33:31–33. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Muir T, Kirsten M, Fourie P, Dippenaar N

and Ionescu GO: Intralesional bleomycin injection (IBI) treatment

for haemangiomas and congenital vascular malformations. Pediatr

Surg Int. 19:766–773. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Omidvari S, Nezakatgoo N, Ahmadloo N,

Mohammadianpanah M and Mosalaei A: Role of intralesional bleomycin

in the treatment of complicated hemangiomas: Prospective clinical

study. Dermatol Surg. 31:499–501. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Enjolras O, Brevière GM, Roger G, Tovi M,

Pellegrino B, Varotti E, Soupre V, Picard A and Leverger G:

Vincristine treatment for function- and life-threatening infantile

hemangioma. Arch Pediatr. 11:99–107. 2004.(In French). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ezekowitz RA, Mulliken JB and Folkman J:

Interferon alfa-2a therapy for life-threatening hemangiomas of

infancy. N Engl J Med. 326:1456–1463. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hochman A and Mascareno A: Management of

nasal hemangiomas. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 7:295–300. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hamou C, Diner PA, Dalmonte P, Vercellino

N, Soupre V, Enjolras O, Vazquez MP and Picard A: Nasal tip

haemangiomas: Guidelines for an early surgical approach. J Plast

Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 63:934–939. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zheng JW, Zhou GY, Wang YA and Zhang ZY:

Management of head and neck hemangiomas in China. Chin Med J

(Engl). 121:1037–1042. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E,

Hubiche T, Boralevi F, Thambo JB and Taïeb A: Propranolol for

severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 358:2649–2651. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Price CJ, Lattouf C, Baum B, McLeod M,

Schachner LA, Duarte AM and Connelly EA: Propranlol vs

corticosteroids for infantile hemangiomas: A multicenter

retrospective analysis. Arch Dermatol. 147:1371–1376. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Storch CH and Hoeger PH: Propranolol for

infantile haemangiomas: Insights into the molecular mechanisms of

action. Br J Dermatol. 163:269–274. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ribatti D: The crucial role of vascular

permeability factor/vascular endothelial factor in angiogenesis: A

historical review. Br J Haematol. 128:303–309. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ye XX, Jin YB, Lin XX, Ma G, Chen XD, Qiu

YJ, Chen H and Hu XJ: Topical timolol in the treatment of

periocular superficial infantile hemangiomas: A prospective study.

Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 28:161–164. 2012.(In Chinese).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Coppens G, Stalmans I, Zeyen T and

Casteels I: The safety andefficacy of glaucoma medication in the

pediatric population. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 46:12–18.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Guo S and Ni N: Topical treatment for

capillary hemangioma of the eyelid using beta-blocker solution.

Arch Ophthalmol. 128:255–256. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Prey S, Voisard JJ, Delarue A, Lebbe G,

Taïeb A, Leaute-Labreze C and Ezzedine K: Safety of propranolol

therapy for severe infantile hemangioma. JAMA. 315:413–415. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Pope E and Chakkittakandiyil A: Topical

timolol gel for infantile hemangiomas: A pilot study. Arch

Dermatol. 146:564–565. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xu Y, Xue L, Wei J, Lei B, Liu Z and Wang

X: Oral propranolol treatment for infants with proliferating

hemangiomas: Clinical analysis of 35 cases. Zhongguo Kouqiang He

Mian Waike Zazhi. 10:159–162. 2012.(In Chinese).

|

|

32

|

Zheng JW, Zhou Q, Yang XJ, Wang YA, Fan

XD, Zhou GY, Zhang ZY and Suen JY: Treatment guideline for

hemangiomas and vascular malformations of the head and neck. Head

Neck. 32:1088–1098. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zheng JW: Comment on efficacy and safety

of propranolol in the treatment of parotid hemangioma. Cutan Ocul

Toxicol. 30:333–334. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Xu DP, Cao RY and Tong S: Topical timolol

maleate for superficial infantile hemangiomas: an observational

study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 73:1089–1094. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chan H, Mckay C, Adam S and Wargon O: RCT

of timolol maleate gel for superficial infantile hemangiomas in

5-to 24-week-olds. Pediatrics. 131:e1739–e1747. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li G, Xu DP, Tong S, Xue L, Sun NN and

Wang XK: Oral Propranolol With Topical Timolol Maleate Therapy for

Mixed Infantile Hemangiomas in Oral and Maxillofacial Regions. J

Craniofac Surg. 27:56–60. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Storch CH and Hoeger PH: Propranolol for

infantile hemangiomas: Insights into the molecular mechanisms of

action. Br J Dermatol. 163:269–274. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Itinteang T, Brasch HD, Tan ST and Day DJ:

Expression of components of the renin-angiotensin system in

proliferating infantile hemangioma may account for the

propranolol-induced accelerated involution. J Plast Reconstr

Aesthet. 64:759–765. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|