Introduction

Neuropathic pain is a common complication of cancer,

diabetes mellitus, degenerative spine disease, infection with the

human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

and various other infectious diseases; it has a profound effect on

an individual's quality of life and health care expenditures

(1). Up to 7–8% of the European

population is affected, and 5% of individuals may experience severe

neuropathic pain (2). Neuropathic

pain may result from disorders of the peripheral nervous system or

the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). Notably,

neuropathic pain can be particularly difficult to treat with only

40–60% of sufferers achieving partial relief (3). Favored treatments include certain

antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressant and

serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), anticonvulsants

(pregabalin and gabapentin), and topical lidocaine (4). Opioid analgesics are recognized as

useful agents but are not recommended as first line treatments. The

efficacy and safety of pregabalin has been extensively

characterized in previous studies, and the findings have been

positive (3,5). Therefore, pregabalin is currently one

of the recommended first-line treatments for neuropathic pain

(3,5). In particular, its efficacy has been

demonstrated in a number of randomized controlled trials in

patients with neuropathic pain caused by various different events

and diseases (6–9).

The present study compared combination therapy with

pregabalin and morphine with each drug used as a single agent in

320 patients with chronic neuropathic pain.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 320 patients (males:females, 1.1:1) with

chronic neuropathic pain, who were at least 18 years old (range,

18–89 years), were enrolled in the present study between November

2009 and October 2010. Pain intensity varied from moderate to

severe. Patients with cancer pain and those who were unsuccessfully

treated with pregabalin were excluded from the present analysis.

The protocol for the present study was approved by the Research

Ethics Board of Shenyang Medical College (Shenyang, China). Written

informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to their

enrollment on the study. All study protocols were in accordance

with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Agents

Patients received oral morphine (MS CONTIN;

Mundipharma International, Ltd., Cambridge, UK) monotherapy, oral

pregabalin (Lyrica; Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY, USA) monotherapy,

or a combination of morphine plus pregabalin for 90 days. These

pharmacological agents were used in line with the manufacturers'

prescribing information and as required by the patient, according

to their condition. The initial mean daily dose of morphine was

36.4 mg in the monotherapy group, and 25.5 mg for the combination

therapy group. The initial mean daily dose of pregabalin was 86.2

mg in the monotherapy group and 106.3 mg in the combination therapy

group. Treatment dosages were altered based on the pain intensity

recorded at visits and telephone interviews on the days of 7, 14,

21, 28, 35, 56, 75 and 90 in order to achieve optimal efficacy and

tolerability based on their response and adverse events. If

necessary, immediate release morphine (oral morphine 5 or 10 mg per

day) was used for breakthrough pain.

Study design

In our single center, an open-label, prospective

comparison of three treatments (morphine, pregabalin and these

drugs in combination) was conducted. Patients receiving pregabalin

who had partial pain control were assigned to the pregabalin

monotherapy group for 90 days (n=102); patients feeling pain which

was not controlled by other drugs were randomized into the morphine

group (n=90) or the morphine and pregabalin combination group for

90 days (n=128). The patient number was not consistent between the

three treatment groups as some patients refused to take morphine in

the combination of morphine plus pregabalin group. Patients in the

morphine groups who refused to take morphine were exempted from the

study.

Efficacy and tolerability were the primary endpoints

evaluated. Pain relief was the primary measure of efficacy and pain

intensity was continually assessed for the eight follow-up visits

(days 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 56, 75 and 90). Patients were asked to

rate pain during the past 24 h on a numerical rating scale (NRS),

where 0 indicated no pain and 10 was the worst pain imaginable. A

2-point reduction was described as clinically meaningful by Farrar

et al (10) and Rowbotham

(11). Secondary endpoints included

comparisons of daily dosages for monotherapy vs. combination

therapy at the end of treatment, impact on quality of life (QoL),

and patient assessments of treatment efficacy. The interference of

pain with QoL was compared for each of the three treatment

regimens. A Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) questionnaire was utilized

to evaluate how the patient's everyday life was influenced by pain

during the study (12,13). The BPI questionnaire evaluates pain

intensity using an NRS (0, no pain; 10, worst pain imaginable) and

the impact of pain on QoL, by rating how pain interferences with

the following seven domains: General activity, mood, walking,

normal work, sleep, social relations and life enjoyment, using an

NRS (0, does not interfere; 10, completely interferes). In order to

investigate the tolerability of each treatment, adverse events were

recorded at each of the eight follow-up visits. Furthermore,

patients were asked to assess the effectiveness of the treatment by

giving one of the following ratings: Not effective, slightly

effective, effective or very effective.

Statistical analysis

Baseline disease characteristics were compared among

the three different treatment groups. The results were presented as

the mean ± standard deviation or the percentage of patients.

χ2 tests were used to analyze categorical data.

P<0.01 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0

software for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

The patient protocol is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 128 patients were

assigned to the combination group of morphine plus pregabalin;

however, 24 were excluded from the study due to adverse events.

Similarly, the number of patients in the morphine monotherapy group

and the pregabalin monotherapy group were reduced from 90 to 15 and

from 102 to 16, respectively, due to adverse events. Adverse events

included blurred vision, abnormal coordination, memory impairment,

dry mouth and constipation, abnormal walking, asthenia and

dysarthria. Details of withdrawal are shown in Fig. 1. Four patients in the morphine

monotherapy group, four patients in the pregabalin monotherapy

group and 13 patients receiving combination therapy were lost to

follow-up.

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table I. There were numerous causes of

neuropathic pain in the present study, including: Failed back

surgery syndrome, post-herpetic neuralgia, radiculopathy, painful

diabetic neuropathy and stenosis of the spinal medullary canal.

Concerning patients with post-herpetic neuropathy, there were fewer

patients in the morphine group compared with the other two

treatment groups, and other diseases were of a similar incidence

among the three groups. Also, the mean score of pain was similar

between the groups receiving monotherapy and those exposed to

morphine and pregabalin combination therapy, both of which were

higher than the mean score in the pregabalin monotherapy group.

| Table I.Patient characteristics. |

Table I.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Morphine | Pregabalin | Morphine +

Pregabalin |

|---|

| Patients | 90 | 102 | 128 |

| Male | 42 | 59 | 60 |

|

Female | 48 | 43 | 68 |

| Disease (%) |

|

|

|

| Stenosis

MSC | 20.8 | 19.1 | 21.3 |

| FBSS | 23.1 | 20.2 | 19.8 |

| PHN | 15.5 | 22.2 | 23.6 |

| DPN | 16.3 | 17.8 | 16.7 |

|

Radiculopathy | 24.3 | 20.7 | 18.6 |

| NRS (mean

score) | 7.5 | 5.6 | 7.2 |

Pain intensity

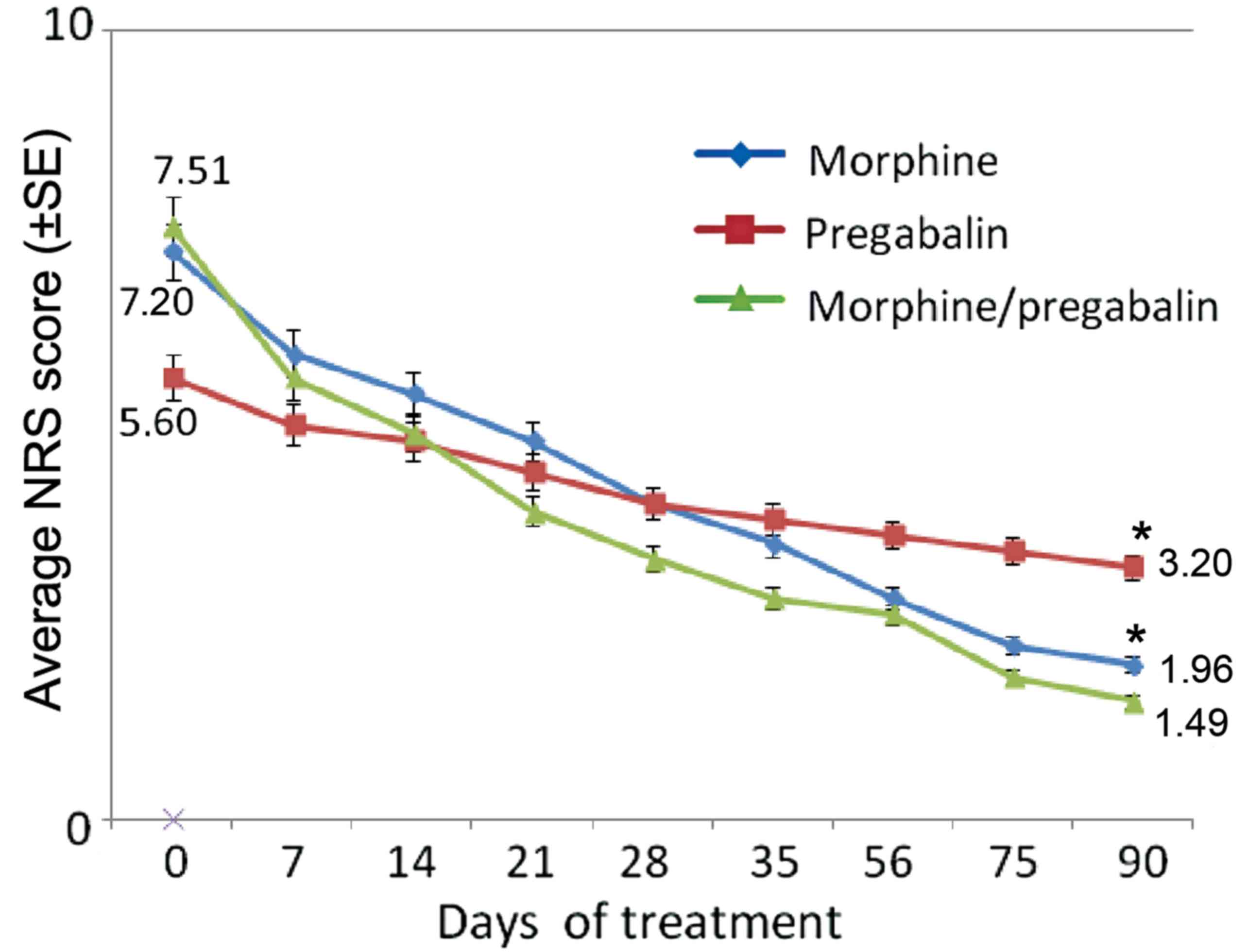

Morphine plus pregabalin combination therapy and

morphine monotherapy resulted in much faster pain relief than

pregabalin monotherapy (Fig. 2).

After 90 days, compared with the baseline, the mean NRS score of

the combination therapy group had decreased by 80.2%. This value

decrease was significantly greater than that of the two monotherapy

groups. The mean NRS score of the pregabalin monotherapy group had

only decreased by 42.9% (P<0.01 vs. combination therapy);

whereas that score in the morphine monotherapy group had decreased

by 72.8% (P<0.01 vs. combination therapy).

Daily pain crises

At baseline, the three groups had a similar mean

number of breakthrough pain events per day (morphine plus

pregabalin, 3.63; morphine, 3.15; pregabalin, 3.05). At the end of

the study, patients that had received morphine plus pregabalin

combination therapy and those taking morphine monotherapy showed a

significant decrease in the mean number of breakthrough pain events

per day compared with the pregabalin monotherapy group (P<0.01;

Fig. 3).

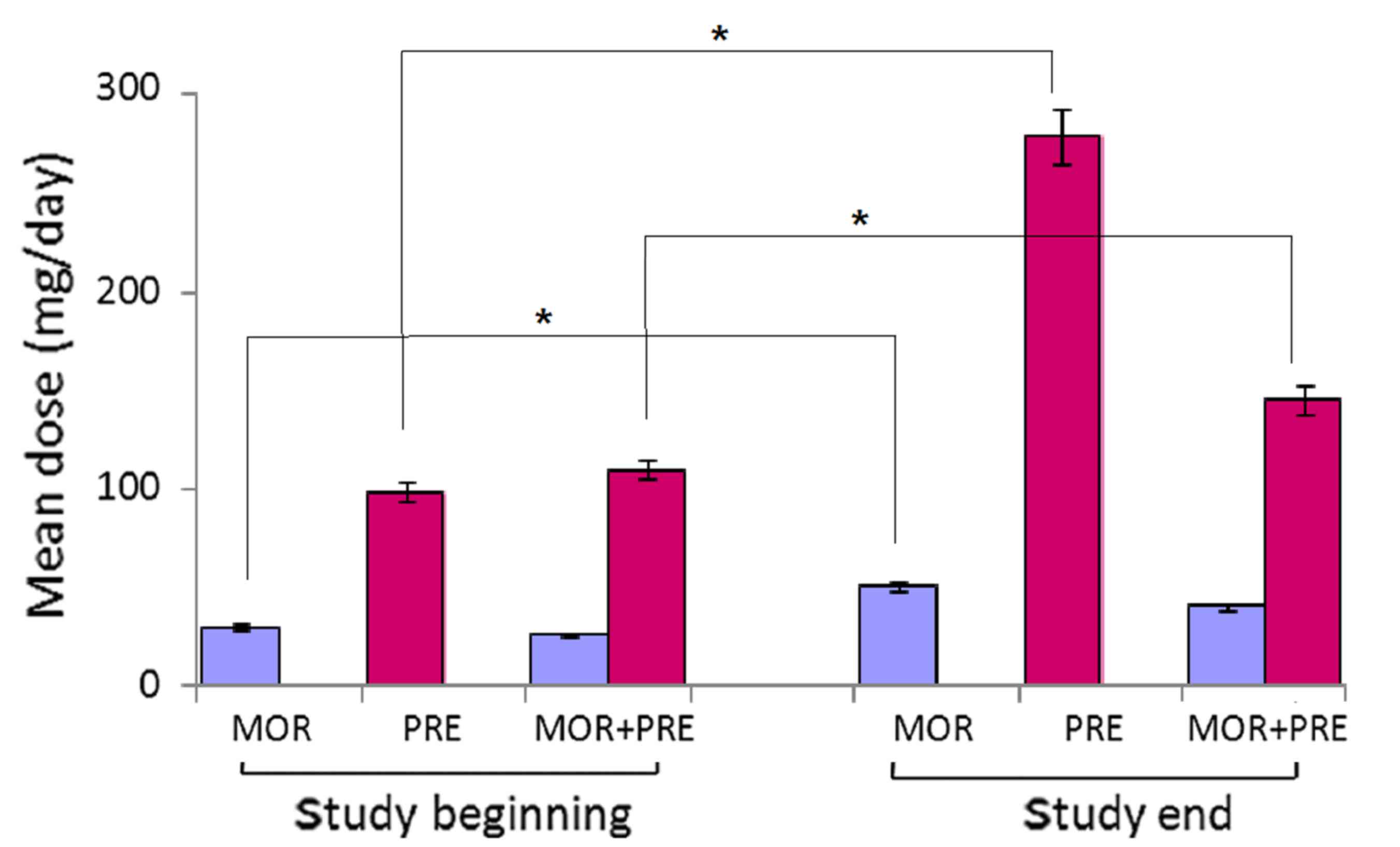

Mean daily medication doses

Combination treatment was effective at lower mean

doses of morphine and pregabalin compared with either morphine or

pregabalin monotherapy, respectively (Fig. 4). In the morphine monotherapy group,

the mean daily doses were 31.2 and 52.8 mg at the beginning and the

end of the study, respectively. In the combination group of

morphine plus pregabalin, the mean daily doses were 26.4 and 110.3

mg at the beginning, respectively, and 41.8 and 142.5 mg at the

end, respectively,. In the pregabalin monotherapy group, the mean

daily doses were 99.6 and 286.3 mg at the beginning and the end of

the study, respectively.

Quality of life

The interference of pain with activities of daily

life was substantially reduced after 90 days treatment in patients

taking morphine plus pregabalin compared with the monotherapy

groups. After 90 days of treatment, patients receiving combination

therapy also exhibit improvements in other OoL terms, including

walking, normal work and social relations. Furthermore, combination

therapy exhibited lower scores than the other two monotherapy

groups, respectively. (Table

II).

| Table II.Impact of three different therapies on

quality of life. |

Table II.

Impact of three different therapies on

quality of life.

|

| Pregabalin | Morphine | Pregabalin +

Morphine |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | Begin | End | Begin | End | Begin | End |

|---|

| General activity | 6.31 | 3.24 | 7.54 | 2.75 | 7.58 | 2.34 |

| Mood | 5.16 | 2.81 | 6.77 | 2.30 | 6.21 | 1.67 |

| Walking | 6.21 | 3.45 | 8.11 | 3.13 | 7.64 | 2.33 |

| Normal work | 6.09 | 3.59 | 7.14 | 2.44 | 7.98 | 2.09 |

| Social relations | 4.65 | 2.24 | 6.05 | 3.11 | 6.97 | 2.41 |

| Sleep | 4.12 | 2.32 | 6.87 | 2.57 | 6.64 | 2.44 |

| Life enjoyment | 4.20 | 2.42 | 6.22 | 2.73 | 6.81 | 2.05 |

The overall decrease in BPI scores at the end of

study compared with the baseline was 72.1% for combination

treatment (P<0.01 vs. either monotherapy), 61.8% for morphine

monotherapy, and 39.8% for pregabalin monotherapy (Fig. 5).

Patient evaluation of efficacy

After 90 days of treatment, 92.2% of patients taking

combination therapy and 93.9% of patients receiving morphine

described the therapy as ‘effective’ or ‘very effective’. In

contrast, in the group taking pregabalin monotherapy, just 18.8% of

patients found the therapy to be ‘effective’ or ‘very effective’

(Fig. 6).

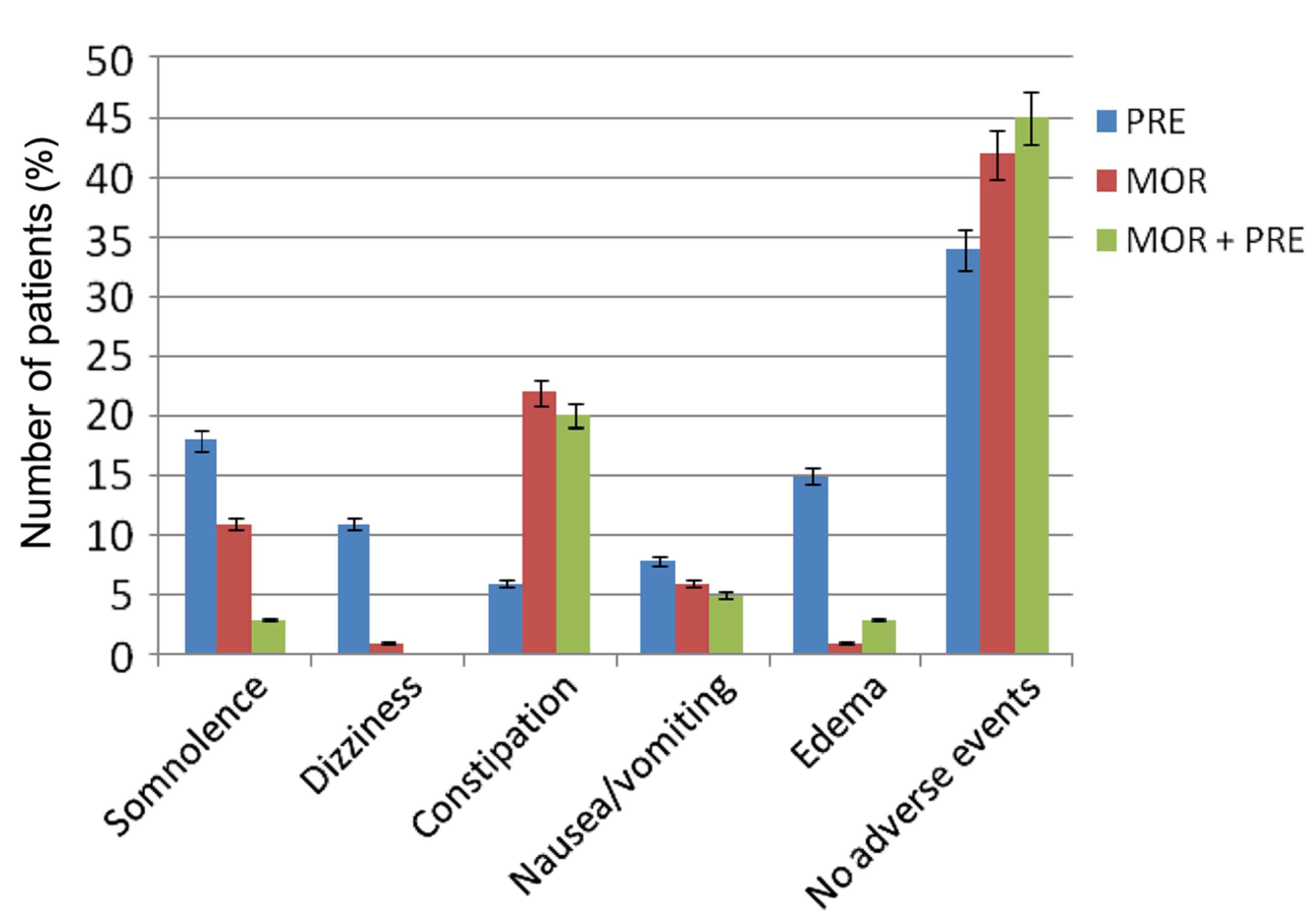

Safety analysis

In sum, patients receiving combination therapy had a

better safety profile than patients receiving either morphine or

pregabalin monotherapy. The most frequent adverse events were

somnolence and peripheral edema with pregabalin, and constipation

with morphine (Fig. 7). Constipation

was most associated with combination therapy. Notably, the

frequency of adverse events tended to decrease with the duration of

the study. After 90 days of therapy, 57.3% of patients receiving

combination therapy, 51.8% of patients receiving morphine and 36.9%

of patients receiving pregabalin monotherapy exhibited no adverse

events.

Combination therapy markedly reduced adverse events

compared with the two monotherapy groups (Fig. 7). The incidence of peripheral edema

was significantly improved in the combination therapy group

compared with the pregabalin monotherapy group (P<0.01). Nausea

and vomiting were also improved in the combination treatment

compared with other two monotherapy groups.

Discussion

The present results suggest that treatment of

neuropathic pain with pregabalin and morphine combination therapy

results in less pain than treatment with either pregabalin or

morphine as a single agent, as indicated by patients' pain

intensity and responses to pain questionnaire in the present

study.

In terms of pain relief, the efficacy of combined

morphine and pregabalin was significantly better than that of

morphine monotherapy, and was similar to pregabalin monotherapy.

The pain intensities exhibited by patients in the combination group

and the morphine monotherapy group were markedly decreased compared

with pregabalin monotherapy (80.2 and 72.8 vs. 42.9%). In the two

groups, this finding was considered to be clinically relevant

because the decrease in pain scores from baseline to the end of the

study was >2 points (10,11). Our study is in agreement with the

substantial opioid responsiveness for neuropathic pain reported by

another study, which focused on opioid based therapies (14). Other aspects of pain relief were also

improved by combination treatment with morphine plus pregabalin and

morphine monotherapy compared with pregabalin treatment. The number

of breakthrough pain events per day was decreased in the

combination and morphine therapy groups, compared with the

pregabalin group.

Compared with monotherapy, combination therapy

required lower mean dosages of morphine and pregabalin to induce

pain relief. This is particularly relevant to the management of

chronic conditions that require long-term treatment, due to the

potential for adverse events and addiction with opiod analgesics

(15).

QoL is a useful measure of the influence of chronic

conditions on the daily activities of patients. In the present

study, patients' total scores for the intensity of pain were

significantly lower in the combination therapy group, as compared

with the two monotherapy groups. Furthermore, combination treatment

was accompanied with less interference of pain with activity, mood,

walking, normal work, social relations, sleep and enjoyment of

life.

The present study showed that morphine-based therapy

may greatly improve treatment compliance. This is based on evidence

that patients receiving morphine-based treatment were more

satisfied with their condition, when compared with pregabalin

monotherapy. At the end of the study, >90% of patients who

received morphine monotherapy or combination therapy gave positive

ratings (‘effective’ and ‘very effective’), whereas <20% of

patients receiving pregabalin reported that treatment was

effective.

According to published data, adverse events in line

with opioid treatment were more common and persistent, particularly

constipation. In the present study, compared with patients who

received monotherapy, only a small proportion of patients had their

daily lives interrupted because of adverse events. Nevertheless, in

the combination therapy group, adverse events tended to decline in

frequency as the study duration increased.

The results of the present study indicate the

excellent efficacy of therapy combination with pregabalin and

morphine in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Given the potential

benefits and drawbacks of drug combinations, a randomized

controlled study is required to investigate whether dosages could

be further reduced to improve safety, and how the combination of

the two drugs may be optimized to achieve long-term pain relief. In

conclusion, combination treatment with morphine and pregabalin is

effective and may be adopted as a therapeutic option for the

treatment of patients suffering from neuropathic pain.

References

|

1

|

Schmader KE: Epidemiology and impacton

quality of life of postherpetic neuralgiaand painful diabetic

neuropathy. Clin J Pain. 18:350–354. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bouhassira D, Lantéri-Minet M, Attal N,

Laurent B and Touboul C: Prevalence of chronic pain with

neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain.

136:380–387. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Backonja M,

Farrar JT, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, Kalso EA, Loeser JD, Miaskowski

C, Nurmikko TJ, et al: Phgroupacologic management of neuropathic

pain: Evidence based recommendations. Pain. 132:237–251. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Audette J, Baron

R, Gourlay GK, Haanpää ML, Kent JL, Krane EJ, Lebel AA, Levy RM, et

al: Recommendations for the pharmacological management of

neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin

Proc. 85:(Suppl 3). S3–14. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Attal N, Cruccu G, Haanpää M, Hansson P,

Jensen TS, Nurmikko T, Sampaio C, Sindrup S and Wiffen P: EFNS Task

Force: EFNS guidelineson phgroupacological treatment of neuropathic

pain. Eur J Neurol. 13:1153–1189. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rosenstock J, Tuchman M, LaMoreaux L and

Shgroupa U: Pregabalin for the treatment of painful diabetic

peripheral neuropathy: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Pain. 110:628–638. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lesser H, Shgroupa U, LaMoreaux L and

Poole RM: Pregabalin relieves symptoms of painful diabetic

neuropathy: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 63:2104–2110.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Richter RW, Portenoy R, Shgroupa U,

Lamoreaux L, Bockbrader H and Knapp LE: Relief of painful diabetic

peripheral neuropathy with pregabalin: A randomized,

placebo-controlled trial. J Pain. 6:253–260. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Freynhagen R, Strojek K, Griesing T,

Whalen E and Balkenohl M: Efficacy of pregabalin inneuropathic pain

evaluated in a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre,

placebo-controlled trial of flexible- and fixed-dose regimens.

Pain. 115:254–263. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth

JL and Poole RM: Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain

intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale.

Pain. 94:149–158. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rowbotham MC: What is a ‘clinically

meaningful’ reduction in pain? Pain. 94:131–132. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Cleeland CS and Ryan KM: Pain assessment:

Global use of the Brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore.

23:129–138. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bonezzi C, Nava A, Barbieri M, Bettaglio

R, Demartini L, Miotti D and Paulin L: Validazione della versione

italiana del Brief Pain inventory nei pazienti con dolore cronico.

Minerva Anestesiol. 68:607–611. 2002.(In Italian). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Watson CP, Moulin D, Watt-Watson J, Gordon

A and Eisenhoffer J: Controlled-release oxycodone relieves

neuropathic pain: A randomized controlled trial in painful diabetic

neuropathy. Pain. 105:71–78. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Eisenberg E, McNicol ED and Carr DB:

Efficacy and safety of opioid agonists in the treatment of

neuropathic pain of nonmalignant origin: Systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 293:3043–3052.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|