1. Introduction

Biofilm-associated infections in otorhinolaryngology

(ORL) pose a significant clinical challenge due to their inherent

resistance to antimicrobial therapy and immune defenses. These

infections contribute to chronic and recurrent conditions, such as

chronic rhinosinusitis, otitis media and tonsillitis, leading to

prolonged patient morbidity and a growing healthcare burden

(1-5).

Biofilms also frequently develop on tracheostomy and airway stents,

often forming within 1 week postoperatively, regardless of material

type. This can facilitate biofilm spread to the lower airways,

increasing the risk of pneumonia and sepsis (1-5).

Despite conventional treatment approaches, biofilm persistence in

ORL structures hinders disease resolution, necessitating

alternative therapeutic strategies (6-9).

Consequently, biofilm-associated infections pose significant

challenges, highlighting the urgent need for innovative

pharmacological strategies to disrupt biofilm formation.

The mechanisms underlying biofilm formation are

complex, involving changes in phenotypic traits, antibiotic

resistance and gene expression (1-3).

Pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P.

aeruginosa) and Staphylococcus aureus (S.

aureus), are frequently implicated, exhibiting strong biofilm

formation in the sinuses and middle ears (1,4-6).

The intricate anatomy of ORL structures, including the narrow sinus

ostia, middle ear cavity and deep tonsillar crypts, fosters

bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. These niches shield

bacteria from immune defenses and antibiotic penetration,

contributing to recurrent infections and treatment failures

(3,6).

Effectively managing biofilm-associated infections

requires innovative pharmacological approaches beyond conventional

antibiotics. Recent research highlights promising strategies, such

as quorum sensing inhibitors (QSIs), that disrupt bacterial

communication essential for biofilm formation (7-9).

Antibiofilm peptides, such as natural and synthetic cationic

peptides, effectively hinder biofilm growth and enhance

antimicrobial efficacy by disrupting bacterial membranes or

modulating gene expression (10,11).

Additionally, repurposing non-antibiotic drugs, such as statins and

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), has emerged as a

potential for targeting biofilm pathogens while complementing

existing therapies (12-14).

Biofilm formation plays a crucial role in the

persistence of ORL infections, necessitating the development of

innovative therapeutic strategies. Advancing our understanding of

biofilm development mechanisms and exploring alternative approaches

(such as QSIs, antibiofilm peptides and drug repurposing) presents

promising opportunities to improve treatment outcomes. The present

review examines current drug mechanisms targeting biofilm formation

and highlights the need for further research into biofilms in ORL

infections.

2. Biofilm formation in ORL infections

Mechanisms of biofilm formation

ORL bacterial infections can arise from either

planktonic (free-floating) or biofilm-associated bacteria.

Planktonic bacteria are typically more susceptible to antibiotics

and immune defenses. Conversely, biofilm-associated bacteria form

structured communities encased in an extracellular polymeric

matrix, which offers increased resistance to antimicrobial agents

and immune system clearance (15,16).

This difference is crucial, as biofilm-associated infections are

often persistent and recurrent, playing a significant role in

chronic disease progression (15,16).

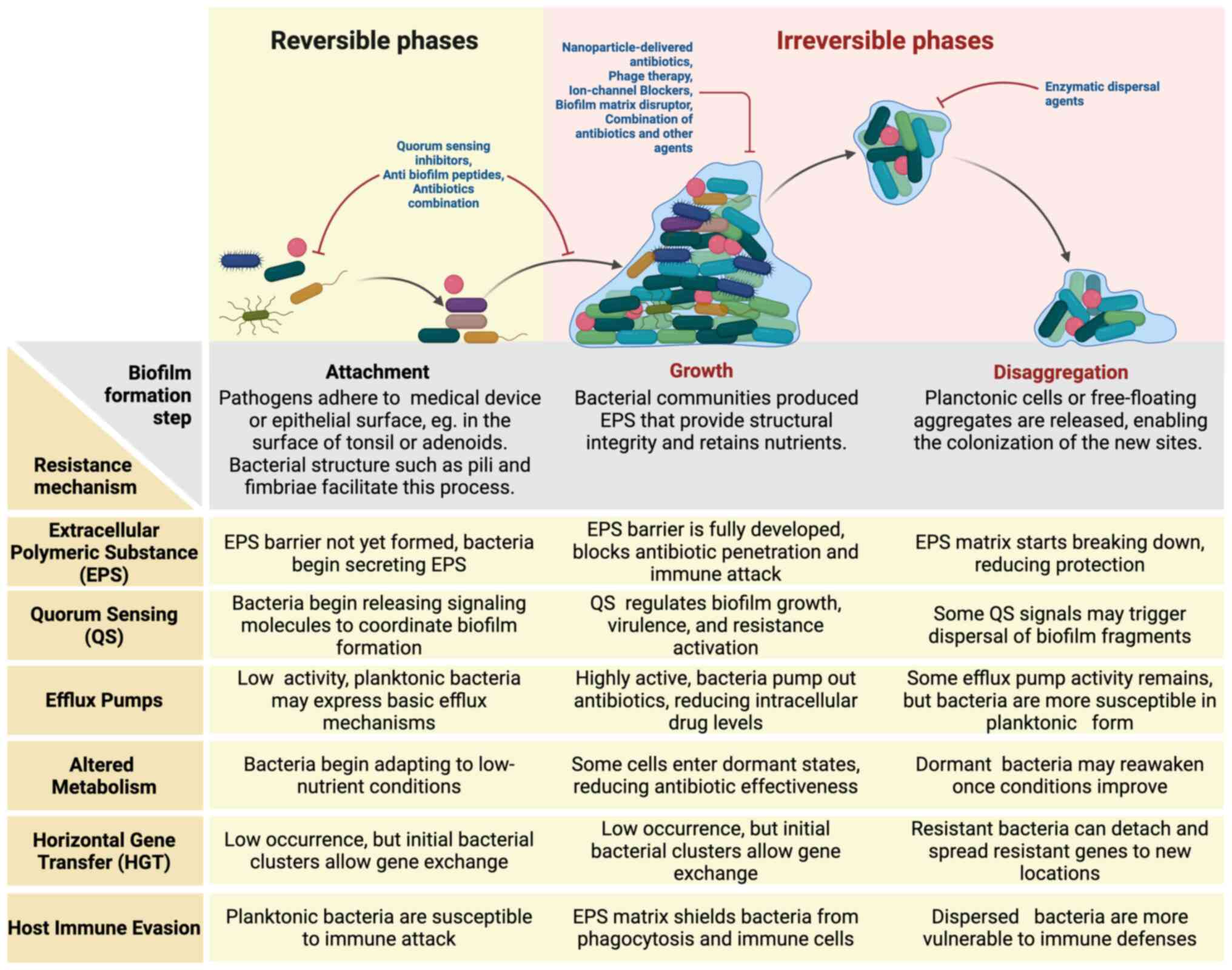

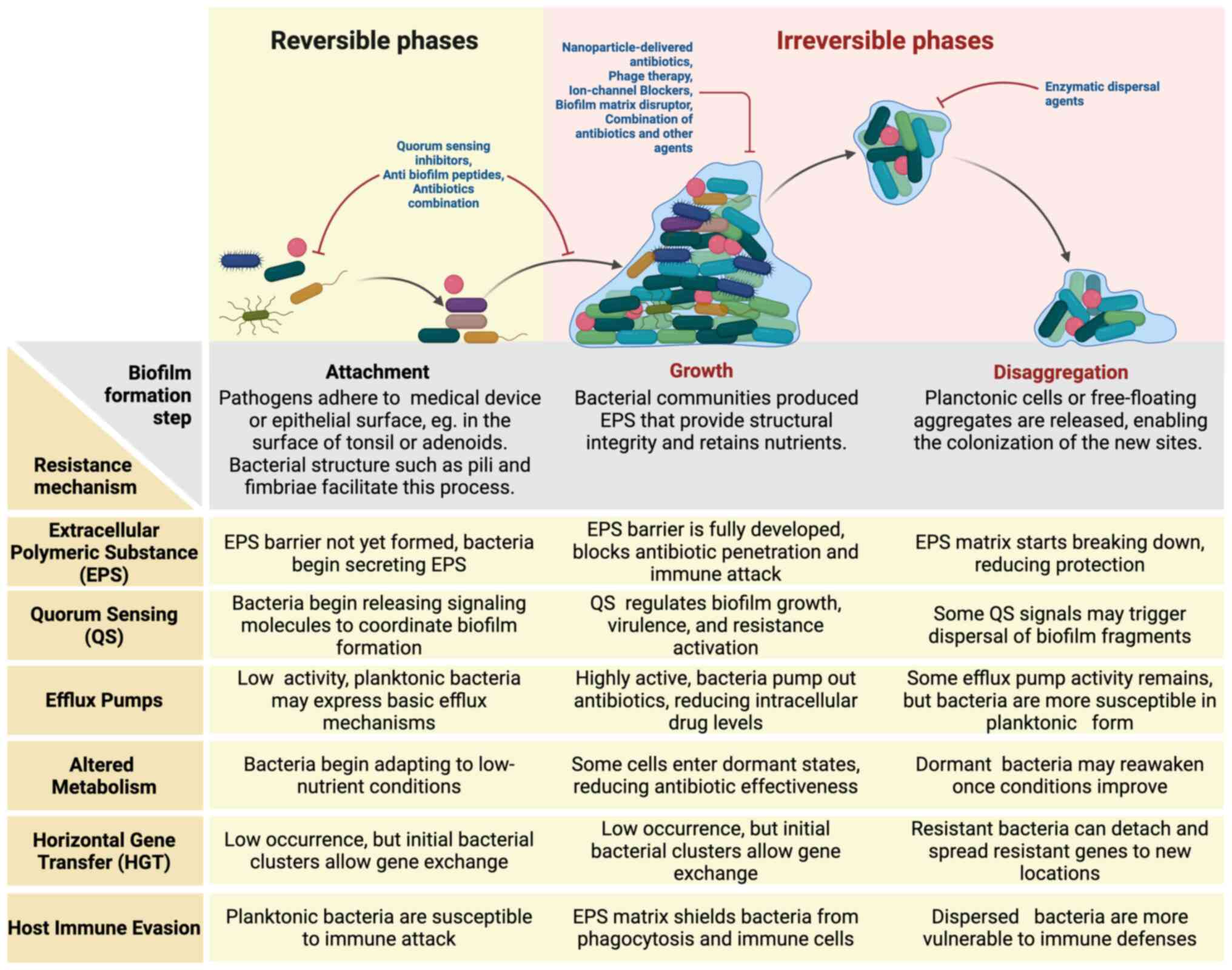

The mechanisms of biofilm formation in ORL involve

dynamic processes that manifest either as surface-attached

structures or free-floating aggregates, reflecting the broader

framework of biofilm formation. These processes are divided into

three key phases (attachment, growth and disaggregation) each

playing a critical role in biofilm persistence and enhancing

bacterial resistance to treatment (Fig.

1) (15,16).

| Figure 1Biofilm formation, resistance

mechanisms and therapeutic strategies in ORL infections. There are

three key phases of biofilm development in otorhinolaryngologic

infections: Attachment, growth and disaggregation. During the

growth phase, bacteria produce extracellular polymeric substances,

enabling resistance through quorum sensing, efflux pumps, altered

metabolism, horizontal gene transfer and immune evasion. Various

antibiofilm strategies have been shown, targeting different stages,

including quorum sensing inhibitors, nanoparticle-based

antibiotics, phage therapy, and enzymatic dispersal agents. This

schematic highlights the persistence of biofilm infections and the

need for targeted therapies. |

The attachment phase represents the initial step in

biofilm formation, during which pathogens adhere to epithelial

surfaces or medical devices. Surface structures, such as pili and

fimbriae, play a key role in this process by enabling bacteria to

anchor firmly to surfaces (15,16).

In ORL, biofilms have been identified on the mucosal surfaces of

the tonsils and adenoids, as well as in the middle ear, where

pathogens, such as S. aureus and Haemophilus

influenzae can colonize (5,6,17,18).

The presence of biofilms in these regions is closely linked to

chronic conditions, such as chronic tonsillitis and otitis media,

highlighting the significance of the attachment phase in the

development and persistence of these infections (5,6,17,18).

In the growth phase, bacterial communities

proliferate and secrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPS),

which assemble into a protective matrix. This matrix not only

ensures structural stability but also retains nutrients and

establishes gradients of oxygen and metabolites, fostering diverse

microenvironments within the biofilm (19,20).

Quorum sensing (QS) regulates gene expression, enabling bacteria to

adjust their metabolism and enhance antibiotic resistance (19,21).

Biofilms in ORL infections mature over time, growing more resistant

and persistent. Consequently, they become less susceptible to

antimicrobial treatments and immune defenses (22).

Previous studies highlight that biofilm growth is

not limited to surface attachment. Free-floating aggregates formed

by bacterial EPS or host-derived polymers can develop within host

tissues and secretions. These aggregates exhibit features similar

to surface-attached biofilms, including antibiotic tolerance and

matrix production, expanding the conceptual understanding of

biofilm formation (15).

The final phase-disaggregation-involves the release

of planktonic cells or fragments from mature biofilms, facilitating

the colonization of new sites and contributing to infection

recurrence (23-25).

This dispersal process is often triggered by environmental changes,

such as nutrient depletion or antibiotic exposure (23-25).

Recent findings challenge the traditional model by showing that

disaggregation can occur in both surface-attached and free-floating

biofilms, further complicating treatment strategies (15). Understanding the formation of

biofilms is essential, as their structural complexity directly

contributes to antibiotic resistance and complicates treatment.

This highlights the need for strategies specifically designed to

address the unique challenges posed by biofilms, as discussed in

the following section.

In summary, biofilm formation involves dynamic and

adaptive processes encompassing surface-associated and

free-floating mechanisms. This revised framework highlights the

importance of developing therapies that target biofilms in all

forms. Understanding these processes is crucial for developing

effective strategies to combat chronic ORL infections.

Pathogens involved in ORL

biofilms

Numerous bacterial and fungal pathogens are

frequently linked to biofilm formation in ORL infections. Key

bacterial species, such as P. aeruginosa, Streptococcus

pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) and S. aureus, are

commonly implicated in chronic conditions such as rhinosinusitis,

otitis media and tonsillitis (Table

I) (4,5,18,22,26-29).

These pathogens adhere to epithelial surfaces and form biofilms,

enabling them to evade host immune defenses and antimicrobial

treatments. Haemophilus influenzae is a significant pathogen

in recurrent otitis media, with its biofilm-forming ability

associated with persistent middle ear infections (18). In fungal biofilms, Candida

spp. and Aspergillus spp. are often implicated in chronic

fungal sinusitis, particularly in immunocompromised patients or

those with underlying conditions, such as allergic fungal sinusitis

(30-33).

| Table ICommon pathogens involved in

biofilm-associated ENT infections. |

Table I

Common pathogens involved in

biofilm-associated ENT infections.

| Pathogen | Infection type | Antibiotic

resistance features | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Pseudomonas

aeruginosa | Chronic

rhinosinusitis, otitis media | Multidrug

resistance, quorum sensing, efflux pumps | (4,5,17,18,26,52) |

| Staphylococcus

aureus | Tonsillitis, otitis

media, sinus infections |

Methicillin-resistance, EPS production,

efflux pumps | (5,17,18,35,38,39) |

| Haemophilus

influenzae | Otitis media, sinus

infections | β-lactam

resistance, biofilm-forming ability | (5,17,18) |

| Streptococcus

pneumoniae | Otitis media, sinus

infections | Penicillin

resistance, efflux pumps, biofilm formation | (4,5,18) |

| Moraxella

catarrhalis | Otitis media, sinus

infections | β-lactam

resistance, biofilm development | (5,18) |

| Klebsiella

pneumoniae | Chronic

rhinosinusitis, sinus infections | Carbapenem

resistance, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production | (4,5,38,39) |

| Escherichia

coli | Sinus infections,

tonsillitis | β-lactam

resistance, efflux pumps, quorum sensing | (3,17,38,39) |

| Candida

spp. | Chronic fungal

sinusitis | Azole resistance,

biofilm growth on mucosal surfaces | (30-33) |

| Aspergillus

spp. | Fungal sinusitis,

chronic invasive infections | Azole resistance,

biofilm-like growth in immunocompromised hosts | (30-33) |

| Proteus

mirabilis | Otitis media, sinus

infections | Biofilm production,

multidrug resistance | (5,18) |

| Acinetobacter

baumannii | Chronic

rhinosinusitis, sinus infections | Carbapenem

resistance, efflux pumps, biofilm-related resistance | (38,39) |

| Enterococcus

faecalis | Chronic ear

infections, sinus infections | Vancomycin

resistance, iron acquisition systems facilitating biofilm

growth | (38) |

Specific environmental and host-related factors

significantly influence the prevalence of biofilm-forming

pathogens. Recurrent infections, prior antibiotic use and medical

procedures such as tympanostomy tube placement create ideal

conditions for biofilm formation. Additionally, biofilms are more

prevalent in patients with chronic inflammation or structural

abnormalities, as these conditions impair normal mucosal defenses

(34-36).

This persistence highlights the need for targeted therapies that

simultaneously disrupt biofilm structure and inhibit microbial

activity to achieve effective treatment outcomes.

3. Challenges in treating biofilm-associated

infections

Challenges related to biofilm

development and treatment agents

A significant challenge in treating

biofilm-associated infections is the increased antibiotic

resistance observed within biofilms. Biofilm-associated infections

hinder effective treatment by restricting antibiotic penetration,

fostering antibiotic resistance, and altering bacterial metabolic

activity, which reduces susceptibility to therapeutic agents.

Biofilm matrices act as physical barriers, shielding embedded

bacteria from antibiotics, while the metabolic dormancy of biofilm

cells further diminishes their responsiveness to treatment.

Bacteria within biofilms often exhibit significantly

higher resistance levels than their planktonic counterparts,

primarily due to the protective biofilm matrix and the presence of

resistance genes, such as those encoding multidrug efflux pumps

(37-39).

The EPS matrix acts as a formidable barrier to drug penetration.

The dense structure of the biofilm, composed of polysaccharides,

proteins and extracellular DNA (eDNA), hinders the diffusion of

antimicrobial agents and reduces their efficacy (40-42).

Consequently, even when antibiotics are administered, they often

fail to achieve the concentrations required to effectively

eliminate bacteria within the biofilm (43,44).

This resistance complicates treatment strategies, as conventional

antibiotics often cannot penetrate the biofilm adequately, enabling

bacterial persistence and leading to chronic infections.

Additionally, biofilms exhibit phenotypic variations

that give rise to subpopulations capable of withstanding

antimicrobial treatments, making elimination more difficult. Within

biofilms, cells often exist in diverse metabolic states, with

numerous entering a dormant or slow-growing phase. This

heterogeneity significantly reduces the effectiveness of

antibiotics, which typically target actively dividing cells

(15,42). To address these challenges,

innovative therapeutic strategies (such as combining physical

disruption, enzymatic degradation, and targeted drug delivery

systems) are essential for improving treatment outcomes.

Current pharmacological strategies focus on three

key objectives-preventing biofilm formation, disrupting established

biofilms, and enhancing the susceptibility of biofilm-embedded

pathogens to antimicrobial agents. Innovative approaches, such as

antibiotic-based strategies, QSIs, antibiofilm peptides, enzymatic

dispersal agents and repurposed drugs, offer promising avenues for

addressing the challenges posed by biofilm-associated

infections.

Challenges related to anatomical and

clinical aspects

The persistence of biofilm-associated infections in

ORL is closely linked to the distinct anatomical features of the

ear, nose and throat, which create protective niches ideal for

microbial colonization. For instance, the sinonasal cavities,

characterized by narrow ostia and complex mucosal folds, create an

environment conducive to biofilm formation and immune evasion

(43,44). In chronic rhinosinusitis, biofilms

drive persistent inflammation and antibiotic resistance, leading to

recurrent infections even after prolonged medical treatment

(43,44). Similarly, in chronic tonsillitis,

the tonsillar crypts act as reservoirs for bacterial biofilms,

harboring deep-seated microbial communities that shield pathogens

from host defenses and antimicrobial agents (45).

In the middle ear, biofilms are a key factor in

recurrent otitis media, particularly in children. Their shorter and

more horizontal Eustachian tubes make it easier for pathogen entry

and persistence (46-48).

Biofilm-forming bacteria, such as Haemophilus influenzae and

S. pneumoniae, often lead to chronic infections that are

challenging to eliminate, necessitating tympanostomy tube placement

(46-48).

The resistance of these biofilms to antibiotic penetration results

in frequent recurrences and extended disease duration, posing a

significant challenge in clinical management (46-48).

The complex ear, nose and throat anatomy,

characterized by narrow and intricate spaces, poses significant

challenges for interventional procedures. These confined regions

impede the effective delivery of enzymatic dispersal agents,

rendering antibiotic-only approaches frequently inadequate for

managing such infections (46-48).

These limitations necessitate a multifaceted treatment approach.

Surgical interventions, including precise mechanical debridement,

are often utilized to physically remove biofilm-affected

tissues.

Given the significant challenges posed by

biofilm-associated infections (such as antibiotic resistance, poor

drug penetration and metabolic adaptations) conventional treatments

often prove inadequate. Therefore, novel therapeutic strategies

aimed at inhibiting biofilm formation, disrupting established

biofilms, and eliminating biofilm-associated bacteria have been

explored. The following sections outline promising pharmacological

approaches, including antibiotic-based strategies, QSIs, enzymatic

dispersal agents, antibiofilm peptides and drug repurposing. These

strategies are designed to enhance treatment efficacy and improve

patient outcomes.

4. Antibiotic-based strategies

Conventional antibiotics

Conventional antibiotics have long been the

foundation for treating bacterial infections, including those

associated with biofilms. However, their efficacy is often limited

in biofilm environments. Biofilm-associated bacteria exhibit

significantly higher resistance to antibiotics than planktonic

bacteria due to factors such as hindered penetration of antibiotics

through the biofilm matrix and altered metabolic activity of

bacteria embedded within the biofilm structure (37-39).

Vancomycin, a standard treatment for methicillin-resistant S.

aureus, is less effective against biofilm-associated

infections, highlighting the need for alternative strategies to

enhance its efficacy (49-51).

The protective EPS matrix and the presence of persister cells

within biofilms hinder antibiotic penetration and reduce metabolic

activity, further diminishing antibiotic effectiveness. Moreover,

prolonged or inappropriate antibiotic use increases the risk of

resistance development, leading to persistent and recurrent

infections. This resistance poses significant challenges in

clinical management.

Combination therapies of antibiotics

with antibiofilm properties

Combination therapy has become a promising approach

for treating biofilm-associated infections. This approach involves

using two or more antimicrobial agents that target different

aspects of bacterial physiology or biofilm structure. For example,

the combination of colistin and tobramycin has shown greater

efficacy in eliminating biofilm-forming P. aeruginosa than

treatments with single agents, as it targets the metabolic

heterogeneity of bacteria within biofilms (52).

Synergistic effects occur when two antibiotics with

distinct mechanisms of action are combined. For example, combining

aminoglycosides, which disrupt protein synthesis, with

beta-lactams, which inhibit cell wall synthesis, enhances

antibacterial activity (53,54).

Synergy is further amplified when one antibiotic exhibits strong

biofilm penetration. Notably, rifampin, known for its ability to

penetrate biofilm and target dormant bacterial populations, has

been effectively combined with vancomycin or daptomycin to treat

biofilm-associated infections caused by Staphylococcus

species (55-57).

These combinations improve biofilm penetration, target both

metabolically active and dormant bacterial cells, and enhance

treatment efficacy while reducing the risk of resistance

development.

Combining antibiotics with biofilm-targeting agents,

such as chelating agents, has emerged as a promising therapeutic

strategy. For example, combining edetic acid (PubChem CID: 6049)

with broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as minocycline has shown the

ability to disrupt biofilm integrity and enhance antibiotic

penetration, thereby improving treatment outcomes (58). Furthermore, topical antibiotics and

silver-containing wound dressings have shown efficacy in reducing

biofilm formation and promoting wound healing in infected tissues,

although supporting evidence remains limited (59,60).

Recent advancements have yielded antibiotics with

targeted antibiofilm properties, designed to either disrupt the

biofilm matrix or inhibit mechanisms critical to biofilm formation.

For example, macrolides, such as azithromycin, exert antibiofilm

effects by interfering with QS, a key bacterial communication

system that regulates biofilm formation and maintenance. By

inhibiting QS, macrolides reduce biofilm integrity and increase

bacterial susceptibility to other antibiotics, particularly in

infections caused by P. aeruginosa and E. coli

(61,62). Tigecycline, a glycyl-cycline

antibiotic, is effective against multidrug-resistant pathogens and

exhibits strong biofilm penetration, targeting both Gram-positive

and Gram-negative bacteria (63).

It has proven particularly effective against MDR Acinetobacter

baumannii and Enterobacteriaceae species (63). Additionally, combining

ceftolozane/tazobactam inhibits biofilm formation and eradicates

established biofilms formed by P. aeruginosa under both

aerobic and anaerobic conditions (64).

Effectively managing biofilm-associated infections

in ORL requires a comprehensive understanding of the limitations of

conventional antibiotic therapies, alongside the adoption of

combination strategies and innovative agents with antibiofilm

properties. By combining these approaches, healthcare providers can

enhance treatment efficacy and improve patient outcomes.

5. Biofilm formation disruptor

QSIs

Bacteria communicate using chemical signaling

molecules called autoinducers, whose concentration rises with

increasing cell density. This process, known as QS, involves

synthesizing, releasing, detecting, and responding to autoinducers.

QS serves as a bacterial communication system that regulates gene

expression based on population density, playing a crucial role in

biofilm formation and virulence (65). In Gram-negative bacteria, such as

P. aeruginosa, QS systems comprise genes encoding

transcriptional regulators (R genes) and autoinducer synthesis

enzymes (I genes). The I genes, such as lasI and

rhlI, facilitate the production of specific autoinducers,

including 3-oxo-C12-HSL and N-butyryl-l-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL)

(65). These autoinducers play a

pivotal role in regulating the expression of virulence factors and

promoting biofilm formation.

In ORL infections, targeting QS presents a promising

strategy for combating biofilm-associated infections, particularly

in chronic conditions such as rhinosinusitis and otitis media. QSIs

disrupt the signaling pathways bacteria use to communicate and

coordinate their behaviors, which are essential for biofilm

formation. By disrupting these pathways, QSIs can suppress the

expression of virulence factors and inhibit biofilm maturation,

rendering bacteria more vulnerable to antibiotics and the host

immune system (8,66). For instance, QSIs can block the

production of key signaling molecules, such as N-acyl homoserine

lactones (AHLs), indole, autoinducer-2 (AI-2), autoinducing

peptide, and diffusible signal factors, which are crucial for

regulating biofilm development in pathogens such as P.

aeruginosa (8,66). By inhibiting these communication

systems, QSIs reduce bacterial virulence and destabilize biofilms,

ultimately enhancing treatment outcomes for chronic infections.

Several compounds have shown efficacy as QSIs.

Natural substances, such as furanone, baicalin and iberin, have

been shown to disrupt QS in various bacterial species, including

P. aeruginosa, by interfering with the synthesis of AHLs

(67-69).

The application of QSIs holds particular promise in treating

chronic rhinosinusitis and otitis media. Chronic rhinosinusitis,

for instance, is often linked to biofilm-forming bacteria,

contributing to persistent inflammation and recurrent infections

(70,71). By targeting QS mechanisms, QSIs can

disrupt biofilm structures, thereby enhancing the efficacy of

conventional antibiotic therapies (9).

Similarly, in otitis media, biofilm formation by

pathogens such as S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus

influenzae often complicate treatment (72). For instance, the LuxS/AI-2 QS system

in S. pneumoniae plays a critical role in biofilm formation

and pathogenicity in middle ear infections (72). QSIs have been shown to reduce

bacterial loads and improve patient outcomes (73), making them a promising therapeutic

strategy for biofilm-associated infections in ORL. By targeting and

disrupting bacterial communication systems, QSIs can enhance the

efficacy of conventional antibiotics and provide a precise approach

to treating chronic infections.

QSIs can potentially prevent biofilm formation, but

their clinical application is hindered by challenges such as

bacterial adaptation and off-target effects. Although certain QSIs,

such as azithromycin, exhibit biofilm-disrupting capabilities,

their efficacy in treating chronic ORL infections requires further

study. Similarly, enzymatic dispersal agents, including DNase I and

Dispersin B, have shown promise in degrading biofilms in

vitro. However, issues related to their stability and methods

for localized delivery pose significant barriers to their broader

adoption in clinical settings.

Biofilm dispersal agents and enzymatic

disruption of EPS

Biofilm dispersal agents and enzymatic approaches

focus on disrupting the EPS that forms the structural backbone of

biofilms. Enzymatic methods offer a direct approach to EPS

disruption. DNase I degrades eDNA, a key structural component that

stabilizes biofilms, thereby compromising their integrity (74,75).

eDNA is essential for maintaining biofilm stability and integrity,

and its degradation by DNase I disrupts biofilm structure,

promoting dispersal and enhancing bacterial susceptibility to

antimicrobials (74,75). Furthermore, treating DNase I can

prevent biofilm reformation by degrading eDNA, which inhibits

bacterial adhesion and aggregation (74,75).

Dispersin B is an enzyme that targets and hydrolyzes

β-1,6-linked N-acetylglucosamine, a key polysaccharide in biofilm

matrices, effectively dispersing biofilms formed by various

bacteria, including S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. When

combined with antibiotics, Dispersin B exhibits a synergistic

effect, significantly reducing bacterial viability compared with

treatment with antibiotics alone (76). Similarly, alginate lyase degrades

alginate, a major component of P. aeruginosa biofilms. This

enzymatic degradation disrupts biofilm structure and improves

antibiotic penetration, particularly in cystic fibrosis-related

infections (77,78).

Nitric oxide (NO) disrupts biofilms by acting as a

signaling molecule that triggers dispersal in P. aeruginosa.

Research indicates that low sublethal concentrations of NO donors,

such as sodium nitroprusside, effectively induce biofilm dispersal

while enhancing bacteria susceptibility to antimicrobial agents

(79). This process is associated

with changes in bacterial metabolism and oxidative stress

responses, destabilizing biofilm structures and facilitating

sessile cell transition to a planktonic state. Consequently,

treatment efficacy against biofilm-associated infections is

significantly enhanced (79).

Combining biofilm-disruption strategies (such as

enzymatic agents and chemical dispersal compounds) with

conventional antimicrobial therapies can significantly improve

treatment outcomes in chronic infections. However, further research

is needed to optimize delivery systems and ensure their safety and

efficacy across various clinical settings. Additionally, future

research should investigate whether combining biofilm dispersal

agents with conventional saline irrigation in biofilm-associated

sinonasal cavity infections can enhance mucociliary clearance,

reduce inflammation, and ultimately improve patients' quality of

life.

Antibiofilm peptides and bacterial

membrane disruptors

Antibiofilm peptides function by compromising the

structural integrity of biofilms and the membranes of the bacteria

they contain. These peptides can penetrate the biofilm matrix

(composed of polysaccharides, proteins and eDNA) leading to biofilm

destabilization and dispersal (80). Furthermore, certain peptides

directly interact with bacterial membranes, inducing membrane

disruption and subsequent cell lysis (80,81).

This dual mechanism, targeting both the biofilm matrix and

bacterial membranes, enhances the effectiveness of antibiofilm

peptides in combating persistent infections.

Numerous antibiofilm peptides have exhibited

significant potential for clinical applications. Among these,

LL-37, a human cathelicidin peptide, stands out for its

broad-spectrum antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities, disrupting

bacterial membranes and modulating immune defenses. Notably, LL-37

has shown promise in disrupting biofilms formed by S. aureus

and P. aeruginosa, enhancing the effectiveness of

conventional antibiotics (82). In

a PREVIOUS study, LL-37 effectively reduced S. aureus

biofilm colony counts by over 4 logs at concentrations of 10 µM or

higher within 24 h, outperforming conventional antibiotics such as

gentamicin and vancomycin (82).

Bacteriocins, ribosomally synthesized peptides

produced by bacteria, exhibit potent antibacterial effects against

closely related species. For example, bacteriocins derived from

Lactobacillus species have been shown to effectively inhibit

biofilm formation by pathogenic bacteria in various settings

(83,84). Specifically, Lactobacillus

acidophilus VB1 exhibits antibacterial and antibiofilm

activities against pathogens linked to chronic otitis media

(85). This strain exerts this

effect through co-aggregation with pathogens and the production of

metabolites, such as cell-free supernatants and biosurfactants,

which disrupt biofilm formation and synergistically enhance the

efficacy of antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin (85).

Synthetic antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) also show

significant potential for eliminating biofilms by disrupting

bacterial membranes or inhibiting biofilm-related gene expression.

For instance, peptide 1018 has proven effective in eliminating

mature biofilms formed by both Gram-negative and Gram-positive

bacteria at concentrations below the minimum inhibitory

concentration. At 0.8 µg/ml, peptide 1018 induced biofilm

dispersal, while higher concentrations (10 µg/ml) achieved

near-complete elimination of biofilm-associated cells (80). Moreover, synthetic peptides can be

engineered to enhance their stability and broaden their efficacy

against diverse biofilm-forming pathogens. A notable example is the

novel antibiofilm peptide, BiF, which was developed through

hybridization with a lipid-binding motif. This dual-function

antimicrobial-antibiofilm peptide hybrid has shown effectiveness

against biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis (86).

Antibiofilm peptides hold significant potential in

preventing and managing recurrent otitis media, a prevalent ear

infection often associated with biofilm formation in the middle

ear. Recurrent otitis media is often linked to biofilm formation on

the tympanic membrane and within the middle ear, resulting in

persistent infections that are challenging to treat using

conventional antibiotics (5,6,17,18).

Further investigation is warranted to determine whether the

targeted delivery of LL-37 and other AMPs, combined with standard

treatment protocols, could significantly reduce the recurrence of

otitis media and sinus cavity infections.

Ion channel blockers

Ion channel blockers offer a novel therapeutic

strategy for treating biofilm-associated infections, particularly

chronic ORL infections. These agents target bacterial ion transport

systems, which are essential for maintaining biofilm integrity. By

disrupting these systems, ion channel blockers can destabilize

biofilms, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of conventional

treatments.

Bacterial biofilms utilize ion gradients to regulate

various cellular processes, including nutrient uptake, waste

removal and membrane potential maintenance, while also facilitating

antibiotic resistance mechanisms. For instance, NorA, an efflux

pump belonging to the major facilitator superfamily of

transporters, expels toxic compounds, including antimicrobial

agents, from bacterial cells (87-89).

Overexpression of NorA in S. aureus enhances its resistance

to antimicrobial treatments and facilitates biofilm formation

(87-89).

Similarly, FeoB in Enterococcus faecalis mediates iron

uptake, enabling enhanced biofilm growth under iron-rich conditions

(90,91). Disrupting these ion transport

systems can compromise biofilm formation and stability, making

bacteria more susceptible to antimicrobial agents.

Gallium compounds have emerged as promising ion

channel blockers due to their ability to mimic iron and disrupt

iron-dependent bacterial processes. Iron serves as a crucial

cofactor for bacterial enzymes involved in DNA synthesis,

respiration and virulence factor production. The structural

similarity of gallium to ferric iron (Fe³+) allows it to

compete for uptake through bacterial iron transport systems, such

as the FeoB transporter and siderophore-mediated pathways (92,93).

Unlike iron, gallium cannot be reduced from Fe³+ to

Fe²+ under physiological conditions, which inhibit key

iron-dependent metabolic enzymes, including ribonucleotide

reductase and superoxide dismutase (93). This disruption impairs bacterial DNA

synthesis, oxidative stress defense and overall biofilm stability.

Consequently, gallium not only prevents biofilm formation but also

enhances bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics. Studies have

shown that gallium compounds, such as gallium nitrate, effectively

inhibit P. aeruginosa biofilms and exhibit synergistic

effects when combined with conventional antimicrobial agents

(92,93).

Calcium channel blockers and proton pump inhibitors

(PPIs) destabilize biofilms by disrupting calcium- and

cation-dependent signaling pathways. Agents such as the calcium

channel blockers nimodipine and verapamil, alongside PPI

dexlansoprazole, block calcium channels associated with the

cyclic-di-GMP signaling cascade (94,95).

This disruption reduces EPS production, weakens biofilm structure,

and promotes the dispersal of biofilms formed by S. aureus,

P. aeruginosa and Candida albicans (94,95).

Ion channel blockers represent a promising strategy

for managing biofilm-associated infections in ORL. Future research

should explore their applicability, safety and efficacy when

combined with conventional antibiotic therapy for chronic

rhinosinusitis and otitis media.

6. Drug repurposing strategies

Drug repurposing, or drug repositioning, involves

exploring existing medications for new therapeutic applications

beyond their original use. This strategy is particularly beneficial

for biofilm-associated infections, as it enables the use of

non-antibiotic drugs with antibiofilm properties. Leveraging the

established safety profiles of these drugs, as well as their

mechanisms of action, clinicians may improve treatment outcomes for

conditions such as recurrent tonsillitis and otitis media.

Drug repurposing for biofilm management leverages

the ability of certain non-antibiotic drugs to disrupt biofilm

formation and stability. These drugs can exert anti-inflammatory

effects, modulate immune defenses, or interfere with bacterial

signaling pathways, ultimately impairing biofilm formation and

persistence.

Several drug classes have been identified as

promising candidates for repurposing in biofilm-associated

infections. Statins, such as atorvastatin and simvastatin, have

been shown to inhibit biofilm formation in various bacterial

species, including S. aureus and P. aeruginosa.

Atorvastatin suppresses the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/MyD88/NF-κB

signaling pathway, promoting anti-inflammatory responses (96,97).

Simvastatin shows bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity against

methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S. aureus

and reduces biofilm formation (98).

Similarly, NSAIDs not only reduce inflammation but

may also disrupt biofilm integrity by modifying the bacterial

microenvironment. Combining ibuprofen with fluoroquinolones

enhances the inhibition of biofilm-associated regulators, including

Alg44 and AlgT/U, as well as the MexB and OprM efflux pump

(12,99). Another study showed that diclofenac

significantly reduced biofilm formation, with inhibition rates

ranging from 22.67-70%, compared with controls (100).

Drug repurposing offers a promising approach for

managing chronic ORL infections, such as recurrent tonsillitis and

otitis media, where biofilm formation drives antibiotic resistance

and treatment failure. Combining repurposed drugs with conventional

antibiotics can enhance biofilm disruption, reduce bacterial load,

and minimize recurrence. However, current evidence on NSAID and

statins primarily stems from in vitro studies, highlighting

the need for further in vivo and clinical

investigations.

7. Emerging and experimental therapies

Advancements in biofilm-associated infection

management have led to the development of innovative and

experimental therapeutic strategies. Notably, nanotechnology-based

therapies and phage therapy offer distinct mechanisms to disrupt

biofilm formation and enhance treatment efficacy.

Nanotechnology

Nanotechnology-based therapies leverage

nanoparticles to enhance drug delivery and enhance the penetration

of antibiotics and antibiofilm agents. These nanoparticles can be

engineered to improve the solubility, stability and bioavailability

of therapeutic agents. By facilitating the targeted delivery of

antibiotics to infection sites, nanoparticles help overcome

biofilm-related barriers to treatment (101-103).

Studies have shown that silver nanoparticles exhibit significant

antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties, effectively disrupting

biofilm formation by pathogens such as P. aeruginosa and

S. aureus (101,102,104,105). Magnetite nanoparticles combined

with antibiotics, such as streptomycin and neomycin, and

encapsulated within biopolymeric spheres exhibit promising

antimicrobial properties and enhanced biocompatibility. These

characteristics make them highly suitable for targeted delivery

systems in ENT infection (106).

Furthermore, polymeric nanoparticles can optimize the controlled

release of antibiofilm agents, promoting sustained therapeutic

effects while minimizing the need for frequent administration

(107).

Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems offer a

promising approach to addressing the limitations of conventional

antibiotics in ORL biofilm infections. Nanoparticles, such as

silver nanoparticles and liposomal antibiotic carriers, have been

shown to penetrate biofilms and enhance antimicrobial efficacy. For

instance, in chronic rhinosinusitis, nanoparticle-based drug

formulations have shown improved retention in sinonasal mucosa,

enhancing local drug concentrations and reducing systemic toxicity

(106,108). However, several challenges, such

as rapid clearance by mucociliary mechanisms, potential cytotoxic

effects on the respiratory epithelium, and the lack of large-scale

clinical trials, limit their immediate clinical application.

Additionally, the regulatory approval process for phage therapy

remains complex due to strain-specific variations and the need for

personalized phage cocktails. Although nanoparticle-based

formulations have shown efficacy in preclinical models of chronic

rhinosinusitis and otitis media, their clinical validation remains

limited (106,108). Future clinical trials evaluating

the safety and efficacy of nanocarriers in targeting

biofilm-associated ORL infections are essential to advance their

translational potential.

Phage therapy

Phage therapy is an innovative approach that employs

bacteriophages (viruses that specifically infect and eliminate

bacteria) to target biofilm-specific pathogens. This method is

particularly promising in addressing antibiotic resistance, as

bacteriophages can effectively disrupt biofilms while eliminating

resistant bacterial strains, all without harming beneficial

microbiota (109-111).

Studies have shown the efficacy of phage therapy in treating

chronic infections caused by biofilm-forming bacteria, such as

P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and Klebsiella sp.,

in chronic wound infection (109-111).

The high specificity of bacteriophages enables targeted treatment,

minimizing collateral damage to surrounding tissues and reducing

the adverse effects often associated with conventional antibiotics

(112). By enhancing the efficacy

of existing treatments and offering alternatives in the face of

increasing antibiotic resistance, phage therapy has significant

potential for improving patient outcomes in chronic ORL

conditions.

It has been previously revealed that phages can

effectively disrupt biofilms in patients with chronic otitis media

and sinus infections by degrading EPS and lysing bacterial cells

(113). However, the clinical

application of phage therapy in ORL faces significant challenges,

including concerns about phage stability in mucosal environments,

potential immune responses and regulatory constraints (114). Although compassionate-use cases

have yielded promising outcomes, large-scale clinical trials are

needed to develop standardized phage formulations, dosing protocols

and comprehensive safety profiles (114). Addressing challenges, such as

mucosal penetration, host immune interactions and large-scale

production, is crucial to integrating these innovative therapies

into mainstream ORL clinical practice.

8. Conclusion and future directions

The present review highlights the pivotal role of

biofilm formation in the persistence and recurrence of ORL

infections, particularly its contribution to antimicrobial

resistance and treatment failure. Emerging pharmacological

strategies, such as QSIs, antibiofilm peptides, enzymatic dispersal

agents and repurposed drugs, offer promising approaches to disrupt

biofilm structural integrity and enhance treatment outcomes

(Tables II and III).

| Table IIAnti-biofilm therapies and their

mechanisms of action. |

Table II

Anti-biofilm therapies and their

mechanisms of action.

| Therapy type | Mechanism of

action | Example agents | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Quorum sensing

inhibitors | Disrupt bacterial

communication, preventing biofilm formation and virulence factor

expression. | Furanones,

Baicalin, Iberin, Azithromycin | (8,65-67) |

| Enzymatic dispersal

agents | Degrade

extracellular polymeric substances and eDNA, breaking biofilm

structure. | DNase I, Dispersin

B, Alginate lyase | (74-77) |

| Anti-biofilm

peptides | Penetrate biofilm,

disrupt bacterial membranes, and modulate gene expression to

inhibit biofilm formation. | LL-37,

Bacteriocins, Synthetic AMPs (e.g., peptide 1018) | (81,82,84) |

| Drug repurposing

strategies | Reuse existing

drugs with anti-inflammatory or biofilm-disrupting properties,

enhancing antibiotic effects. | Statins

(Atorvastatin, Simvastatin), NSAIDs (Ibuprofen) | (12,97,100) |

| Combination

antibiotic therapy | Target different

aspects of bacterial physiology to penetrate biofilm and eradicate

bacteria. | Colistin +

Tobramycin, Vancomycin + Rifampin | (52,54) |

| Nanotechnology

approaches | Deliver drugs using

nanoparticles to enhance penetration, stability, and antimicrobial

action. | Silver

nanoparticles, Magnetite-based carriers | (102,105-107) |

| Phage therapy | Use bacteriophages

to target and lyse bacteria specifically within lyse bacteria

specifically within biofilms. biofilms. | Bacteriophages for

P. aeruginosa, S. aureus | (111,112) |

| Ion channel

blockers | Disrupt ion

gradients and efflux pump activity, weakening biofilm

integrity. | Gallium compounds,

Verapamil, Proton pump inhibitors | (87-89,92,95) |

| Biofilm matrix

disruptors | Target EPS

components to weaken matrix stability, enabling antibiotic

penetration. | Chelating agents

(e.g., EDTA), Nitric oxide donors | (89) |

| Immunomodulatory

approaches | Enhance immune

responses to target biofilm-associated infections and modulate

inflammation. | Immunostimulatory

peptides, Toll-like receptor modulators | (10,13,97) |

| Table IIISummary of effectiveness and

limitation of anti-biofilm therapies. |

Table III

Summary of effectiveness and

limitation of anti-biofilm therapies.

| Therapy type | Effectiveness | Limitations |

|---|

| Quorum sensing

Inhibitors | Effective in early

biofilm stages; reduces virulence | Limited clinical

trials; potential bacterial resistance |

| Enzymatic dispersal

agents | Directly breaks

down biofilms; enhances antibiotic effects | Specificity issues;

potential immune response interference |

| Anti-biofilm

peptides | Broad-spectrum

activity; effective in resistant strains | Expensive;

potential cytotoxicity |

| Drug repurposing

strategies | Cost-effective;

enhances conventional therapy | Limited data on

long-term effects |

| Combination

antibiotic therapy | Synergistic effect;

useful for resistant infections | Risk of toxicity

and antibiotic resistance |

| Nanotechnology

approaches | High penetration;

effective at lower doses | Requires advanced

formulation; regulatory concerns |

| Phage therapy | Specific targeting;

minimal side effects | Narrow spectrum;

requires strain-specific selection |

| Ion channel

blockers | Weakens biofilm

structure; enhances antibiotic action | Limited in

vivo evidence; possible side effects |

| Biofilm matrix

disruptors | Directly weakens

biofilm structure | Risk of toxicity;

variable effectiveness |

| Immunomodulatory

approaches | Potential for

long-term infection control | Complexity of

immune modulation; needs further research |

Despite these advancements, translating these

findings into clinical practice remains challenging, necessitating

further research to validate safety, refine delivery systems, and

assess long-term efficacy. QSIs, for instance, exhibit potential in

preventing biofilm formation, but their clinical application is

hindered by concerns over bacterial adaptation and off-target

effects. Although certain QSIs, such as azithromycin, exhibit

biofilm-disrupting capabilities, their efficacy in treating chronic

ORL infections is still being studied (115). Similarly, enzymatic dispersal

agents, such as DNase I and Dispersin B, have shown promise in

degrading biofilms in vitro, but their stability and methods

for localized delivery remain significant barriers to their broader

clinical application (116).

Antibiofilm peptides exhibit broad-spectrum

activity, but their clinical use is hindered by high production

costs and potential cytotoxicity. While some synthetic AMPs have

advanced to preclinical testing, their pharmacokinetics and

potential immunogenicity require further validation before clinical

adoption (117). Drug repurposing

strategies, such as statins and NSAIDs, have garnered interest due

to their dual anti-inflammatory and biofilm-disrupting effects

(12-14).

However, their effectiveness in treating biofilm-associated ORL

infections remains unclear, as most supporting evidence derives

from in vitro studies and animal models rather than

large-scale human trials.

While in vitro and preclinical studies have

shown promising biofilm-targeting strategies, their efficacy and

practicality in real-world clinical settings remain largely

unverified. Future research must focus on conducting well-designed

clinical trials to assess the effectiveness, safety and

pharmacokinetics of these therapies in patients with chronic

biofilm-associated infections. Additionally, it is essential to

explore patient-specific factors (such as comorbidities, immune

responses and treatment adherence) to ensure successful clinical

implementation. Integrating advanced technologies, such as

nanocarriers, phage therapy and immunomodulatory approaches into

clinically relevant frameworks, will enhance treatment precision

and help translate laboratory findings into practical,

patient-centered applications.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms Rahmati Putri

Yaniafari (Nanyang Technological University, Singapore) for her

assistance in accessing several sources used in the present

review.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are

included in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

MAE, INK and NMS conceptualized the study, drafted

and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript or to generate images, and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the

artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Drenkard E and Ausubel FM: Pseudomonas

biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to

phenotypic variation. Nature. 416:740–743. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Behzadi P, Gajdács M, Pallós P, Ónodi B,

Stájer A, Matusovits D, Kárpáti K, Burián K, Battah B, Ferrari M,

et al: Relationship between biofilm-formation, phenotypic virulence

factors and antibiotic resistance in environmental Pseudomonas

aeruginosa. Pathogens. 11(1015)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chen C, Liao X, Jiang H, Zhu H, Yue L, Li

S, Fang B and Liu Y: Characteristics of Escherichia coli biofilm

production, genetic typing, drug resistance pattern and gene

expression under aminoglycoside pressures. Environ Toxicol

Pharmacol. 30:5–10. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sanderson AR, Leid JG and Hunsaker D:

Bacterial biofilms on the sinus mucosa of human subjects with

chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 116:1121–1126.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Mohammed RQ and Abdullah PB: Infection

with acute otitis media caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa

(MDR) and Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Biochem Cell Arch.

20:905–908. 2020.

|

|

6

|

Bendouah Z, Barbeau J, Hamad WA and

Desrosiers M: Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is associated with an unfavorable

evolution after surgery for chronic sinusitis and nasal polyposis.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 134:991–996. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Carradori S, Di Giacomo N, Lobefalo M,

Luisi G, Campestre C and Sisto F: Biofilm and quorum sensing

inhibitors: The road so far. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 30:917–930.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang Y, Bian Z and Wang Y: Biofilm

formation and inhibition mediated by bacterial quorum sensing. Appl

Microbiol Biotechnol. 106:6365–6381. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zhou L, Zhang Y, Ge Y, Zhu X and Pan J:

Regulatory mechanisms and promising applications of quorum

sensing-inhibiting agents in control of bacterial biofilm

formation. Front Microbiol. 11(589640)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ridyard KE and Overhage J: The potential

of human peptide LL-37 as an antimicrobial and anti-biofilm agent.

Antibiotics (Basel). 10(650)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Martínez M, Polizzotto A, Flores N,

Semorile L and Maffía PC: Antibacterial, anti-biofilm and in vivo

activities of the antimicrobial peptides P5 and P6.2. Microb

Pathog. 139(103886)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Paes Leme RC and da Silva RB:

Antimicrobial activity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on

biofilm: Current evidence and potential for drug repurposing. Front

Microbiol. 12(707629)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Schelz Z, Muddather HF and Zupkó I:

Repositioning of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors as adjuvants in the

modulation of efflux pump-mediated bacterial and tumor resistance.

Antibiotics (Basel). 12(1468)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kumar A, Alam A, Grover S, Pandey S,

Tripathi D, Kumari M, Rani M, Singh A, Akhter Y, Ehtesham NZ and

Hasnain SE: Peptidyl-prolyl isomerase-B is involved in

Mycobacterium tuberculosis biofilm formation and a generic target

for drug repurposing-based intervention. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes.

5(3)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Sauer K, Stoodley P, Goeres DM,

Hall-Stoodley L, Burmølle M, Stewart PS and Bjarnsholt T: The

biofilm life cycle: Expanding the conceptual model of biofilm

formation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 20:608–620. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Irie Y, Borlee BR, O'Connor JR, Hill PJ,

Harwood CS, Wozniak DJ and Parsek MR: Self-produced

exopolysaccharide is a signal that stimulates biofilm formation in

Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

109:20632–20636. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Parastan R, Kargar M, Solhjoo K and

Kafilzadeh F: Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: Structures,

antibiotic resistance, inhibition, and vaccines. Gene Rep.

20(100739)2020.

|

|

18

|

Galli J, Calò L, Ardito F, Imperiali M,

Bassotti E, Fadda G and Paludetti G: Biofilm formation by

Haemophilus influenzae isolated from adeno-tonsil tissue

samples, and its role in recurrent adenotonsillitis. Acta

Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 27:134–138. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Davenport EK, Call DR and Beyenal H:

Differential protection from tobramycin by extracellular polymeric

substances from Acinetobacter baumannii and

Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.

58:4755–4761. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Serra DO, Klauck G and Hengge R: Vertical

stratification of matrix production is essential for physical

integrity and architecture of macrocolony biofilms of Escherichia

coli. Environ Microbiol. 17:5073–5088. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Parsek MR and Greenberg EP:

Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing in gram-negative bacteria: A

signaling mechanism involved in associations with higher organisms.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 97:8789–8793. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Singh GB, Malhotra S, Yadav SC, Kaur R,

Kwatra D and Kumar S: The role of biofilms in chronic otitis

media-active squamosal disease: An evaluative study. Otol Neurotol.

42:e1279–e1285. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Dar D, Dar N, Cai L and Newman DK: Spatial

transcriptomics of planktonic and sessile bacterial populations at

single-cell resolution. Science. 373(eabi4882)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Cornforth DM, Dees JL, Ibberson CB, Huse

HK, Mathiesen IH, Kirketerp-Møller K, Wolcott RD, Rumbaugh KP,

Bjarnsholt T and Whiteley M: Pseudomonas aeruginosa

transcriptome during human infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

115:E5125–E5134. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Dal Co A, Van Vliet S and Ackermann M:

Emergent microscale gradients give rise to metabolic cross-feeding

and antibiotic tolerance in clonal bacterial populations. Philos

Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 374(20190080)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Boase S, Foreman A, Cleland E, Tan L,

Melton-Kreft R, Pant H, Hu FZ, Ehrlich GD and Wormald PJ: The

microbiome of chronic rhinosinusitis: Culture, molecular

diagnostics and biofilm detection. BMC Infect Dis.

13(210)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kostić M, Ivanov M, Babić SS, Tepavčević

Z, Radanović O, Soković M and Ćirić A: Analysis of tonsil tissues

from patients diagnosed with chronic tonsillitis-microbiological

profile, biofilm-forming capacity and histology. Antibiotics

(Basel). 11(1747)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Lee MR, Pawlowski KS, Luong A, Furze AD

and Roland PS: Biofilm presence in humans with chronic suppurative

otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 141:567–571.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Hoa M, Syamal M, Schaeffer MA, Sachdeva L,

Berk R and Coticchia J: Biofilms and chronic otitis media: An

initial exploration into the role of biofilms in the pathogenesis

of chronic otitis media. Am J Otolaryngol. 31:241–245.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Karthikeyan P and Nirmal Coumare V:

Incidence and presentation of fungal sinusitis in patient diagnosed

with chronic rhinosinusitis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

62:381–385. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Bahethi R, Talmor G, Choudhry H, Lemdani

M, Singh P, Patel R and Hsueh W: Chronic invasive fungal

rhinosinusitis and granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis: A

systematic review of symptomatology and outcomes. Am J Otolaryngol.

45(104064)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Yang SW, Luo CM and Cheng TC: Fungal

abscess of anterior nasal septum complicating maxillary sinus

fungal ball rhinosinusitis caused by Aspergillus flavus:

Case report and review of literature. J Fungi (Basel).

10(497)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Leszczyńska J, Stryjewska-Makuch G,

Lisowska G, Kolebacz B and Michalak-Kolarz M: Fungal sinusitis

among patients with chronic rhinosinusitis who underwent endoscopic

sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Pol. 72:35–41. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Marom T, Habashi N, Cohen R and Tamir SO:

Role of biofilms in post-tympanostomy tube otorrhea. Ear Nose

Throat J. 99 (1 Suppl):22S–29S. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Manasherob R, Mooney JA, Lowenberg DW,

Bollyky PL and Amanatullah DF: Tolerant small-colony variants form

prior to resistance within a Staphylococcus aureus biofilm

based on antibiotic selective pressure. Clin Orthop Relat Res.

479:1471–1481. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Habashi N, Marom T, Steinberg D, Zacks B

and Tamir SO: Biofilm distribution on tympanostomy tubes: An ex

vivo descriptive study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.

138(110350)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Mah TF, Pitts B, Pellock B, Walker GC,

Stewart PS and O'Toole GA: A genetic basis for Pseudomonas

aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature. 426:306–310.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Kvist M, Hancock V and Klemm P:

Inactivation of efflux pumps abolishes bacterial biofilm formation.

Appl Environ Microbiol. 74:7376–7382. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Tang M, Wei X, Wan X, Ding Z, Ding Y and

Liu J: The role and relationship with efflux pump of biofilm

formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb Pathog.

147(104244)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Powell LC, Abdulkarim M, Stokniene J, Yang

QE, Walsh TR, Hill KE, Gumbleton M and Thomas DW: Quantifying the

effects of antibiotic treatment on the extracellular polymer

network of antimicrobial resistant and sensitive biofilms using

multiple particle tracking. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes.

7(13)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Kosztołowicz T and Metzler R: Diffusion of

antibiotics through a biofilm in the presence of diffusion and

absorption barriers. Phys Rev E. 102(032408)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Tuon FF, Dantas LR, Suss PH and Tasca

Ribeiro VST: Pathogenesis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa

biofilm: A review. Pathogens. 11(300)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Denton O, Wan Y, Beattie L, Jack T,

McGoldrick P, McAllister H, Mullan C, Douglas CM and Shu W:

Understanding the role of biofilms in acute recurrent tonsillitis

through 3D bioprinting of a novel gelatin-PEGDA hydrogel.

Bioengineering (Basel). 11(202)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Huang Y, Qin F, Li S, Yin J, Hu L, Zheng

S, He L, Xia H, Liu J and Hu W: The mechanisms of biofilm

antibiotic resistance in chronic rhinosinusitis: A review. Medicine

(Baltimore). 101(e32168)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Abu Bakar M, McKimm J, Haque SZ, Majumder

MAA and Haque M: Chronic tonsillitis and biofilms: A brief overview

of treatment modalities. J Inflam Res. 11:329–337. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Schilder AGM, Chonmaitree T, Cripps AW,

Rosenfeld RM, Casselbrant ML, Haggard MP and Venekamp RP: Otitis

media. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2(16063)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Duff AF, Jurcisek JA, Kurbatfinski N,

Chiang T, Goodman SD, Bakaletz LO and Bailey MT: Oral and middle

ear delivery of otitis media standard of care antibiotics, but not

biofilm-targeted antibodies, alter chinchilla nasopharyngeal and

fecal microbiomes. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 10(10)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Niedzielski A, Chmielik LP and Stankiewicz

T: The formation of biofilm and bacteriology in otitis media with

effusion in children: A prospective cross-sectional study. Int J

Environ Res Public Health. 18(3555)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Abdelhady W, Bayer AS, Seidl K, Moormeier

DE, Bayles KW, Cheung AL, Yeaman MR and Xiong YQ: Impact of

vancomycin on sarA-mediated biofilm formation: Role in persistent

endovascular infections due to methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 209:1231–1240.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Rose WE and Poppens PT: Impact of biofilm

on the in vitro activity of vancomycin alone and in combination

with tigecycline and rifampicin against Staphylococcus

aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 63:485–488. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Cho OH, Bae IG, Moon SM, Park SY, Kwak YG,

Kim BN, Yu SN, Jeon MH, Kim T, Choo EJ, et al: Therapeutic outcome

of spinal implant infections caused by Staphylococcus

aureus: A retrospective observational study. Medicine

(Baltimore). 97(e12629)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Herrmann G, Yang L, Wu H, Song Z, Wang H,

Høiby N, Ulrich M, Molin S, Riethmüller J and Döring G:

Colistin-tobramycin combinations are superior to monotherapy

concerning the killing of biofilm Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J

Infect Dis. 202:1585–1592. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Giamarellou H, Zissis NP, Tagari G and

Bouzos J: In vitro synergistic activities of aminoglycosides and

new beta-lactams against multiresistant Pseudomonas

aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 25:534–536.

1984.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Giamarellou H: Aminoglycosides plus

beta-lactams against gram-negative organisms. Evaluation of in

vitro synergy and chemical interactions. Am J Med. 80:126–137.

1986.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Olson ME, Slater SR, Rupp ME and Fey PD:

Rifampicin enhances activity of daptomycin and vancomycin against

both a polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA)-dependent and

-independent Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm. J

Antimicrob Chemother. 65:2164–2171. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Zimmerli W and Sendi P: Role of rifampin

against staphylococcal biofilm infections in vitro, in animal

models, and in orthopedic-device-related infections. Antimicrob

Agents Chemother. 63:e01746–18. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Niska JA, Shahbazian JH, Ramos RI, Francis

KP, Bernthal NM and Miller LS: Vancomycin-rifampin combination

therapy has enhanced efficacy against an experimental

Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infection. Antimicrob

Agents Chemother. 57:5080–5086. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Ferreira Chacon JM, Hato de Almeida E, de

Lourdes Simões R, Lazzarin C, Ozório V, Alves BC, Mello de Andréa

ML, Santiago Biernat M and Biernat JC: Randomized study of

minocycline and edetic acid as a locking solution for central line

(port-a-cath) in children with cancer. Chemotherapy. 57:285–291.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Vermeulen H, van Hattem JM, Storm-Versloot

MN and Ubbink DT: Topical silver for treating infected wounds.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD005486, 2007.

|

|

60

|

Jiang Y, Zhang Q, Wang H, Välimäki M, Zhou

Q, Dai W and Guo J: Effectiveness of silver and iodine dressings on

wound healing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open.

14(e077902)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Tateda K, Comte R, Pechere JC, Köhler T,

Yamaguchi K and Van Delden C: Azithromycin inhibits quorum sensing

in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.

45:1930–1933. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Hoffmann N, Lee B, Hentzer M, Rasmussen

TB, Song Z, Johansen HK, Givskov M and Høiby N: Azithromycin blocks

quorum sensing and alginate polymer formation and increases the

sensitivity to serum and stationary-growth-phase killing of

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and attenuates chronic P.

aeruginosa lung infection in Cftr(-/-) mice. Antimicrob Agents

Chemother. 51:3677–3687. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Gupta S, Aruna C, Nagaraj S, Dias M and

Muralidharan S: In vitro activity of tigecycline against

multidrug-resistant gram-negative blood culture isolates from

critically ill patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 67:1293–1295.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Kostoulias X, Fu Y, Morris FC, Yu C, Qu Y,

Chang CC, Blakeway L, Landersdorfer CB, Abbott IJ, Wang L, et al:

Ceftolozane/tazobactam disrupts Pseudomonas aeruginosa

biofilms under static and dynamic conditions. J Antimicrob

Chemother. 80:372–380. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Miller MB and Bassler BL: Quorum sensing

in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 55:165–199. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Köhler T, Perron GG, Buckling A and van

Delden C: Quorum sensing inhibition selects for virulence and

cooperation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLOS Pathog.

6(e1000883)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Tsikopoulos A, Petinaki E, Festas C,

Tsikopoulos K, Meroni G, Drago L and Skoulakis C: In vitro

inhibition of biofilm formation on silicon rubber voice prosthesis:

Α systematic review and meta-analysis. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat

Spec. 84:10–29. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Jakobsen TH, Bragason SK, Phipps RK,

Christensen LD, van Gennip M, Alhede M, Skindersoe M, Larsen TO,

Høiby N, Bjarnsholt T and Givskov M: Food as a source for quorum

sensing inhibitors: Iberin from horseradish revealed as a quorum

sensing inhibitor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ

Microbiol. 78:2410–2421. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Luo J, Dong B, Wang K, Cai S, Liu T, Cheng

X, Lei D and Chen Y, Li Y, Kong J and Chen Y: Baicalin inhibits

biofilm formation, attenuates the quorum sensing-controlled

virulence and enhances Pseudomonas aeruginosa clearance in a

mouse peritoneal implant infection model. PLoS One.

12(e0176883)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Prince AA, Steiger JD, Khalid AN,

Dogrhamji L, Reger C, Eau Claire SE, Chiu AG, Kennedy DW, Palmer JN

and Cohen NA: Prevalence of biofilm-forming bacteria in chronic

rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 22:239–245. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Foreman A, Holtappels G, Psaltis AJ,

Jervis-Bardy J, Field J, Wormald PJ and Bachert C: Adaptive immune

responses in Staphylococcus aureus biofilm-associated

chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 66:1449–1456. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Yadav MK, Vidal JE, Go YY, Kim SH, Chae SW

and Song JJ: The LuxS/AI-2 quorum-sensing system of

Streptococcus pneumoniae is required to cause disease, and

to regulate virulence- and metabolism-related genes in a rat model

of middle ear infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.

8(138)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Dawit G, Mequanent S and Makonnen E:

Efficacy and safety of azithromycin and amoxicillin/clavulanate for

otitis media in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of

randomized controlled trials. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob.

20(28)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Brown HL, Hanman K, Reuter M, Betts RP and

Van Vliet AHM: Campylobacter jejuni biofilms contain extracellular

DNA and are sensitive to DNase I treatment. Front Microbiol.

6(699)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Tetz GV, Artemenko NK and Tetz VV: Effect

of DNase and antibiotics on biofilm characteristics. Antimicrob

Agents Chemother. 53:1204–1209. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Gawande PV, Leung KP and Madhyastha S:

Antibiofilm and antimicrobial efficacy of

DispersinB®-KSL-W peptide-based wound gel against

chronic wound infection associated bacteria. Curr Microbiol.

68:635–641. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Lamppa JW and Griswold KE: Alginate lyase

exhibits catalysis-independent biofilm dispersion and antibiotic

synergy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 57:137–145. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Daboor SM, Rohde JR and Cheng Z:

Disruption of the extracellular polymeric network of Pseudomonas

aeruginosa biofilms by alginate lyase enhances pathogen

eradication by antibiotics. J Cyst Fibros. 20:264–270.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Barraud N, Hassett DJ, Hwang SH, Rice SA,

Kjelleberg S and Webb JS: Involvement of nitric oxide in biofilm

dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol.

188:7344–7353. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Reffuveille F, de la Fuente-Núñez C,

Mansour S and Hancock REW: A broad-spectrum antibiofilm peptide

enhances Antibiotic Action against bacterial biofilms. Antimicrob

Agents Chemother. 58:5363–5371. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Le CF, Fang CM and Sekaran SD:

Intracellular targeting mechanisms by antimicrobial peptides.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 61:e02340–16. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Kang J, Dietz MJ and Li B: Antimicrobial

peptide LL-37 is bactericidal against Staphylococcus aureus

biofilms. PLoS One. 14(e0216676)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Jalilsood T, Baradaran A, Song AAL, Foo

HL, Mustafa S, Saad WZ, Yusoff K and Rahim RA: Inhibition of

pathogenic and spoilage bacteria by a novel biofilm-forming

Lactobacillus isolate: A potential host for the expression of

heterologous proteins. Microb Cell Fact. 14(96)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar