Introduction

Renal cancer accounts for 5% of all cancer and ranks

as the sixth most prevalent type of cancer in male patients. In

female patients, it contributes to 3% of malignancies and stands as

the tenth most popular form of tumor (1,2).

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for >90% of kidney tumors

(2,3). Depending on population surveys, a

5-year survival rate was observed in 70% of patients diagnosed with

regional cancer. However, for those with metastatic RCC, this rate

drops down to 13% (4). Clear cell

RCC (ccRCC) is the most common histological subtype of RCC,

accounting for 75% of cases, which develops in the epithelium of

kidney tubules and can metastasize to different organs (5).

The inactivation of the tumor suppressor gene Von

Hippel Lindau (VHL) has a key role in the pathogenesis of clear

cell carcinoma (6). It was

demonstrated that >90% of patients with ccRCC experience a loss

of VHL heterozygosity and inactivating mutations of VHL are

detected in 50-65% of instances (7,8).

Reducing the level of VHL proteins directly promotes an increase in

the expression of both hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) including

HIF-1A and HIF-2A (9). These

factors activate various target genes in the tumor microenvironment

which are stimulating tumor cell survival, cell proliferation,

angiogenesis, metabolism of sugar and tumor metastasis (10-12).

Targeting HIFs or downstream effector molecules in the VHL/HIF

pathway (such as VEGFs) has been used for three decades in the

treatment of disease outcomes in advanced patients with ccRCC

(13).

Sunitinib is one of the earliest approved

multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) that have been

extensively used as first-line treatment for metastatic ccRCC

(14). TKIs act by inhibiting the

kinase activity of various receptors and are still used in therapy

(15). Notably, despite its

demonstrated efficacy in treating advanced RCC, a substantial

proportion of patients develop primary resistance or acquired

resistance to sunitinib within 6-15 months of treatment (16). BAY-876 was previously identified as

a new-generation inhibitor of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) in

ovarian cancer (17); however,

since its discovery, there have been no studies investigating the

effect of BAY-876 as GLUTI in ccRCC.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a gaseous

transmitter found in mammalian tissues; along with nitric oxide

(NO) and carbon monoxide (CO), it has a variety of biological

functions (18,19). Other studies demonstrated that

H2S gas has a dual effect on cancerous diseases, acting

as both a pro- and antitumor agent (20,21).

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaSH) salt is a solid analog of H2S

gas that provides immediate and direct access to biologically

significant forms of sulfide. NaSH has been used extensively as an

exogenous delivery method for H2S to evaluate its

therapeutic potential (22). To

the best of the authors' knowledge, the effects of NaSH and BAY-876

on RCC remain unclear and a significant number of patients with

ccRCC have demonstrated a lack of response, recurrence, or

resistance to sunitinib. For these reasons, the present study aimed

to investigate the effects of NaSH and BAY-876 alone and in

combination with sunitinib on ccRCC cells. The evaluation of

genotypic variations and polymorphisms in the VHL and kinase insert

domain receptor (KDR) genes in patients with ccRCC was another aim

of the present study.

Materials and methods

Cell line

The human metastatic ccRCC cell line (786-O) was

obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (cat. no.

CRL-1932). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 31800089) which was supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% of antibiotic (consisting

of 10,000-unit penicillin, 10 mg streptomycin and 25 µg

amphotericin; Sigma Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no. A5955). Cells

were split every 2-3 days to maintain their density and maintained

at 37˚C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% air

(RS Biotech Galaxy Model R+). Following an adaptation step of three

passages, the experiments were conducted within passages 11 to 16

of 786-O cells (23).

Determining IC50

To determine the IC50 of sunitinib

(MedChemExpress; cat. no. HY-10255A), BAY-876 (MedChemExpress; cat.

no. HY-100017) and NaSH on 786-O viability, cells were seeded in a

96-well culture plate (4x103 cell/well) and incubated at

37˚C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. After 24 h,

the cells were treated with various concentrations of sunitinib

(range, 1-100 µM), BAY-876 (range, 10-1,000 µM) and NaSH (range,

10-103 µM) in quadruplicate for each concentration. The

plates were incubated for 24, 48 and 72 h at 37˚C with 5%

CO2. For BAY-876 another plate was incubated for 96 h.

After each incubation interval, the culture media of the plate

wells were changed with new media and then the cell cytotoxicity

was measured by using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; MedChemExpress;

cat. no. HY-K0301) (24) according

to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, 10 µM of the CCK-8

reagent was added to each well, incubated for 2-4 h at 37˚C and

then the absorbance was measured at 540 nm by using an ELIZA reader

(BioTek Instruments, Inc.). Each experiment was carried out three

times.

Drug combinations

The IC50 of sunitinib after 72 h

(5.26x10-6 M), BAY-876 after 96 h (53.56x10-6

M) and NaSH after 72 h (692x10-6 M) were used to

determine the cytotoxicity of the combination of drugs against

786-O cells. Briefly, 4x103 cells/well were seeded in 96

well plates and incubated at 37˚C with 5% CO2. After 24

h incubation, the cells were exposed to the IC50 of each

drug alone and a combination of sunitinib with BAY-876, sunitinib

with NaSH and BAY-876 with NaSH. Following incubation for 24 and 48

h at 37˚C and 5% CO2, cell cytotoxicity was measured by

using the CCK-8 kit.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted via GraphPad Prism 9

Software (Dotmatics). Non-linear regression was employed to

establish the IC50 of medications, while ordinary

one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was performed

to assess the statistically significant differences in the

anticancer activity between various agents and untreated cells. The

data were reported as the mean value ± standard error (SE) of the

difference. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

tissues of patients with ccRCC

A total of 30 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

tissues (FFPE) of patients with ccRCC were collected form PAR and

Rzgary teaching hospitals (Erbil, Iraq) between July 2022 and May

2023. After histological confirmation of ccRCC through hematoxylin

and eosin (H&E) staining, the blocks were collected for

extraction of DNA. The approval (approval no. 45/90) of the present

study was granted by the Human Ethics Committee of the College of

Education of Salahaddin University-Erbil (Erbil, Iraq). The study

was conducted according to the criteria set by The Declaration of

Helsinki (October 2013) and signed informed consent forms were

obtained from the participants approving the use of their tissues

for investigation. DNA samples were extracted from the FFPE

tissues. Clinicopathological characteristics of patients (including

sex and age distribution) are presented in Table I.

| Table IClinicopathological characteristics

of patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. |

Table I

Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

| Clinicopathological

characteristics | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Sex | |

|

Male | 44.40 |

|

Female | 56.60 |

| Age, years | |

|

>50 | 50 |

|

51-60 | 20 |

|

61-70 | 20 |

|

<71 | 10 |

| Degree of

differentiation | |

|

Well-differentiated

tumor | 43.33 |

|

Moderately

differentiated tumor | 50 |

|

Poorly

differentiated | 6.66 |

| TNM staging | |

|

Stage I | |

|

pT1a

N0 Mx | 50 |

|

pT1b

N0 Mx | 26.60 |

|

Stage

II | |

|

pT2

N0 Mx | 3.33 |

|

Stage

III | |

|

pT1b

N1 Mx | 6.33 |

|

pT3a

Nx Mx | 3.66 |

|

pT3a

N0 Mx | 6.33 |

|

pT3

N1 Mx | 3.33 |

Stage assessment of ccRCC

The TNM cancer staging system provides significant

predictors of prognosis in RCC. The present study used the eighth

edition (TNM8) of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and

the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) for ccRCC tumor

staging (25,26). In TNM, the T refers to the size and

regional extension of the primary tumor, the N refers to the tumor

involvement in the regional lymph nodes and the M refers to

metastasis or spread of the tumor to other parts of the body away

from the original location (27).

DNA extraction from FFPE tissues

Genomic DNA extraction from FFPE was performed using

the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue kit (Qiagen GmbH; cat. no. 56404)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 5-µm thick

ribbon sections were created from the paraffin blocks, followed by

deparaffination by xylene. The cells were lysed with lysis buffer

and proteinase k. The DNA bound to the membrane and the

contaminants were flowing through the membrane. Finally, pure DNA

was eluted from the membrane with an elution buffer. The eluted DNA

was quantified based on the absorbance (A) measured at 260 nm

(A260) and purity was estimated based on the A260/A280 ratio using

a Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). An elution buffer was

used as a blank for the Nanodrop instrument. The assessment of DNA

purity relied on an ideal A260/A280 ratio of 1.8(28).

Genotype determination

The current study examined variants of each VHL and

KDR gene. Based on the results of a previous study, exon 1 of VHL

(29) and exon 13 of KDR genes

were chosen for the current study. Initially, the purified DNA

underwent an independent process of amplification. For this

purpose, a pre-prepared master mix (including dNTP,

MgCl2, Taq DNA polymerase and PCR reaction buffer;

Promega Corporation) and the following primer pairs were used: VHL

forward, 5'-GTCTGGATCGCGGAGGGAAT-3' and reverse,

5'-GGACTGCGATTGCAGAAGAT-3'; KDR forward, 5'-CGTGTCTTTGTGGTGCACTG-3'

and reverse, 5'-CTAGGACTGTGAGCTGCCTG-3'. The thermocycling

conditions used for PCR were: Initial denaturation at 95˚C for 5

min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for 30 sec, annealing at

61˚C for 30 sec and extension at 72˚C for 1 min; final elongation

at 72˚C for 6 min and the samples were maintained at 4˚C.

The PCR products were separated by 1.5% agarose gel

electrophoresis. DNA ladder of 100 base pairs (GeneDireX, Inc.;

cat. no. DM003-R500) was used for band composition as shown in

Fig. S1. Before pouring it into

the tray, the gel was mixed with Safe gel stain Dye (ADD BIO) and

then it was visualized using the UV Transilluminator UST-20M-8K

(Biostep GmbH). Following the PCR protocol, the products were

delivered to the cytogenetic laboratory-Zheen International

Hospital-Erbil-Iraq for sequencing performed on the Automatic 3130

Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) using the same forward primers for each exon in the genes.

The sequencing data were deposited into the GenBank database

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/; accession no.

OR294044 and OR339875). Analysis and interpretation of the Sanger

sequencing data were performed using the Mutation Surveyor software

package 5.1 (SoftGenetics, LLC) by comparing the sequencing results

with reference genes in public databases, including ClinVar, dbSNP,

gnomAD and COSMIC (30).

Database's gene mutation retrieval and

gene interactions

Genome aggregation database (gnomAD) version 3.1.2

(https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org)

was used for mutation retrieval of selected genes. This population

referencing database currently is one of the most powerful tools

that provides information about genetic variation and gene

interpretation found in the human population. This resource is

developed by worldwide investigators who collect and integrate both

genome and exome data from massive sequencing programs. The

database nowadays is widely used in clinical genetics and genomic

research (31).

All recorded gene mutations of chosen genes (VHL and

KDR) in RCC were retrieved from both the Mutagene database

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/mutagene) and

Catalog of Somatic Mutation of Cancer (COSMIC v98, released

23-MAY-23; https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic). The Mutagene

database contains 441 RRC samples with 33,063 gene mutations. Based

on Bscore thresholds, Mutagene is used to determine the

cancer driver, potential cancer driver and passenger mutations of

selected genes. COSMIC, which is readily available to researchers

globally, is a thorough database encompassing somatic mutations in

cancer. It provides extensive information about mutation location,

frequency and impact, along with clinical and pathological data. By

utilizing this database, researchers can identify prevalent

mutations and other genetic changes that potentially play a role in

the development or advancement of cancer. Moreover, these findings

may offer potential targets for therapeutic interventions (32).

In addition, the interaction of VHL and KDR genes in

RCC is predicted through the GeneMANIA anticipation tool

(https://genemania.org/). Based on genetic

connection, physical protein-protein interaction and co-expression

pattern, this public online database can provide gene interaction.

By examining the anticipated associations among these two genes,

valuable insights into their participation in cellular processes

and disease pathways can be gained. This, in turn, could pave the

way for the identification of fresh therapeutic targets or

diagnostic biomarkers. GeneMANIA through anticipation of gene

interaction will lead to determining the function of genes,

uncovering gene interaction in specific cellular assays (33) and identifying potential gene

candidates for further study.

Results

Anticancer activity of sunitinib,

BAY-876 and NaSH

To determine the in vitro cytotoxic effect of

sunitinib, BAY-876 and NaSH, dose-dependent viability studies were

performed to find the appropriate concentration of each drug that

can eliminate 50% (IC50) of 786-O cells by using the

CCK-8 kit. The IC50s for sunitinib were found to be

9.85x106, 9.1x10-6 and 5.26x10-6 M

at 24, 48 and 72 h, respectively (Fig.

1A), with no significant difference among the measured

timepoints. The IC50 for BAY-876 was reached only after

4 days of treatment and it was 53.56x10-6 M (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the present study

also revealed that the IC50 for NaSH as an exogenous

donor of H2S after 24 and 48 h of treatment were equal

to 726x10-6 and 692x10-6 M, respectively

(Fig. 1C), with no significant

difference between the two timepoints.

| Figure 1Time- and dose-dependent effect of

(A) sunitinib, (B) BAY-876 and (C) NaSH on viability of 786-O

cells. Cell viability (%) was expressed as the percentage of

treated cells versus log of concentration. Data are expressed as

the mean values ± standard error. The *, ■, ʈ, ⊗, Ψ and ᵶ represent

significant difference in the cytotoxicity effect of specific

concentration between 24 and 48, 48 and 72, 48 and 96, 24 and 96,

72 and 96 and 24-72 h of incubation respectively. ■,

ᵶP<0.05, ʈʈ, Ψ Ψ,

ᵶ ᵶP<0.01 and ***, ■ ■

■, ʈʈʈ, ⊗⊗⊗, ΨΨΨ,

ᵶᵶᵶP<0.001. |

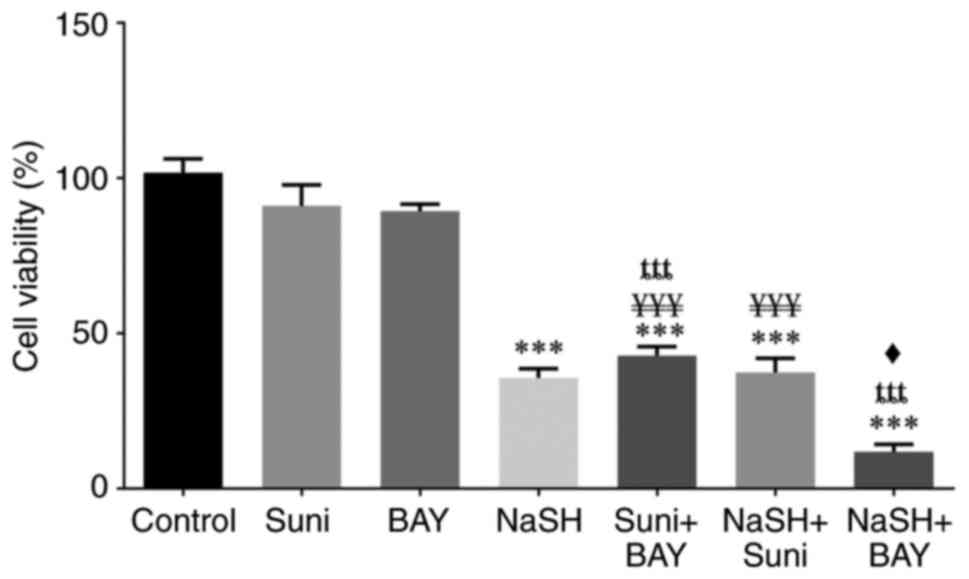

In addition, the cytotoxic effect against 786-O

cells of several drug combinations was assessed. Sunitinib

IC50 after 3 days, BAY-IC50 after 4 days and

NaSH after 2 days were used alone and in combination for 24

(Fig. 2) and 48 h (Fig. 3). The results after 24 h

demonstrated that there were no significant differences in

cytotoxicity between sunitinib and BAY-876 treatments alone

compared with the control group; however, their combination

demonstrated statistically different cytotoxicity (P<0.001)

compared with the control group and each drug used

individually.

| Figure 3Cytotoxicity effect of sunitinib,

BAY-876 and NaSH alone and in combination against 786-O cells after

48 h of treatment. The *, ¥, ȶ and ♦ represent statistical

differences from control, sunitinib, BAY-876, and NaSH

respectively. Each column represents the mean of four data; three

independent experiments were performed. ♦P<0.05,

**, ♦♦P<0.01 and ***, ¥¥¥,

ȶȶȶP<0.001. |

Regarding the cytotoxic effect of NaSH, NaSH alone

and in combination with either sunitinib or BAY-876 revealed a

statistically significant increase (P<0.001) in cytotoxicity

compared with the control group. The cytotoxicity of NaSH in

combination with BAY-876 was significantly higher (P<0.05)

compared with NaSH alone. However, there was no significant

difference between NaSH and sunitinib co-treatment and NaSH.

The outcomes of the drug combinations at 24 and 48 h

were comparable and the only exception was that there was a

statistically significant difference (P<0.05) between the NaSH

and sunitinib co-treatment and NaSH alone in reducing cell

viability.

Patient characteristics

In the current study, out of 30 patients with ccRCC,

17 were male (56.6%) and 13 were female (44.40%). Regarding the

patient age, 50 (50%) were under 50 years, 6 (20%) were between 51

and 60 years, 6 (20%) were between 61 and 70 years, and 3 (10%)

were >71 years old. The degree of cell differentiation varied

among patients with ccRCC. A large number of patients were grouped

as medium-differentiated (50%) and well-differentiated carcinomas

(43.33%), while poorly-differentiated carcinomas accounted only for

6.66% (Table I).

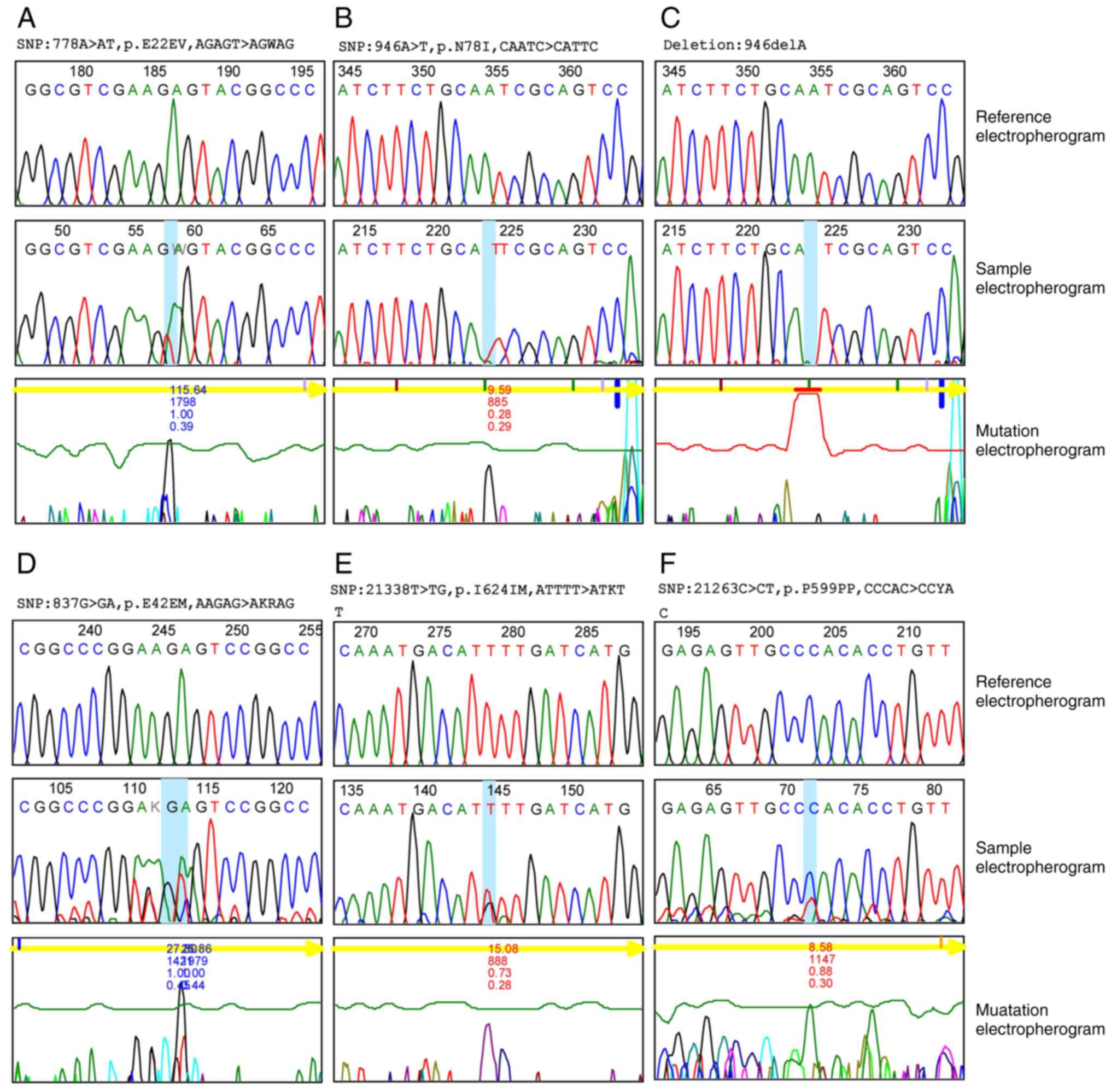

Mutation analysis

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was recorded in

47.7% of the VHL gene and 31.5% of the KDR gene (data not shown).

In exon 1 of the VHL gene of ccRCC, 36 SNP mutations were

identified, including 35 substitution mutations (A>AT, C>CT,

A>AG, G>GA, T>TC, C>CA, A>T) and one deletion

mutation (delA). Both heterozygous (n=35) and homozygous (n=1)

variant mutations were identified as demonstrated in Fig. 4. In total, 35 variant mutations

were previously not recorded in external databases and 30 of them

had their sequences of amino acids changed (Table II). The single homozygous

substitution variant (946A>T) accounts for the greatest

percentage (40%) among all other variants; however, among

heterozygous variants, two heterozygous variants (778A>AT and

793A>AT) constitute the second greatest percentage (33.30%)

among other mutation of VHL gene.

| Table IIVariants identified in VHL and KDR

genes in ccRCC patients analyzed with mutation DNA variant

analysis. |

Table II

Variants identified in VHL and KDR

genes in ccRCC patients analyzed with mutation DNA variant

analysis.

| | Chromosome

position | Mutation | Mutation

enotype |

Heterozygous/Homozygous | Variants | Variant percentage

(%) | Amino acid

change | External

database |

|---|

| VHL gene |

|---|

| 1 | 3:10183764 | Substitution | A>T | Homozygous | 946A>T | 40.00 |

Asparagine/Isoleucine | Not found |

| 2 | 3:10183623 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 805A>AT | 30.00 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 3 | 3:10183626 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 808A>AT | 30.00 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 4 | 3:10183638 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 820A>AT | 30.00 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 5 | 3:10183641 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 823A>AT | 30.00 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 6 | 3:10183656 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 838A>AT | 30.00 | Glutamic

acid/Methionine | Not found |

| 7 | 3:10183671 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 853A>AT | 30.00 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 8 | 3:10183673 | Substitution | C>CA | Heterozygous | 855C>CA | 10.00 |

Lucine/Methionine | Not found |

| 9 | 3:10183686 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 868A>AT | 30.00 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 10 | 3:10183730 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 912A>AT | 18.20 |

Asparagine/Tyrosine | Not found |

| 11 | 3:10183570 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 752A>AT | 25 | none | Not found |

| 12 | 3:10183578 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 760A>AT | 25 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 13 | 3:10183581 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 763A>AT | 25 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 14 | 3:10183582 | Substitution | G>GA | Heterozygous | 764G>GA | 25 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 15 | 3:10183596 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 778A>AT | 33.30 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 16 | 3:10183597 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 793A>AT | 33.30 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 17 | 3:10183612 | Substitution | A>AG | Heterozygous | 794A>AG | 22.20 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 18 | 3:10183635 | Substitution | C>CT | Heterozygous | 817C>CT | 30.00 | Alanine/Valine | Not found |

| 19 | 3:10183655 | Substitution | G>GA | Heterozygous | 837G>GA | 10 | Glutamic

acid/Methionine | Not found |

| 20 | 3:10183611 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 793A>AT | 33.30 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 21 | 3:10183614 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 796A>AT | 11.10 | Aspartic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 22 | 3:10183764 | Deletion | A | | 946delA | 25 | none | Not found |

| 23 | 3:10183635 | Substitution | C>CT | Heterozygous | 817C>CT | 30.00 | Aspartic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 24 | 3:10183579 | Substitution | G>GA | Heterozygous | 761G>GA | 12.50 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 25 | 3:10183608 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 790A>AT | 11.10 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 26 | 3:10183624 | Substitution | G>GA | Heterozygous | 806G>GA | 10.00 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 27 | 3:10183740 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 922A>AT | 16.70 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 28 | 3:10183672 | Substitution | A>AG | Heterozygous | 854A>AG | 9.10 | Glutamic

acid/Valine | Not found |

| 29 | 3:10183762 | Substitution | C>CT | Heterozygous | 944C>CT | 10 | none | Not found |

| 30 | 3:10183763 | Substitution | A>AG | Heterozygous | 945A>AG | 12.50 |

Isoleucine/Valine | Not found |

| 31 | 3:10183691 | Substitution | A>AT | Heterozygous | 873A>AT | 9.10 |

Methionine/Leucine | Not found |

| 32 | 3:10183753 | Substitution | C>CT | Heterozygous | 935C>CT | 8.30 | none | Not found |

| 33 | 3:10183759 | Substitution | C>CT | Heterozygous | 941C>CT | 9.10 | none | Not found |

| 34 | 3:10183756 | Substitution | C>CT | Heterozygous | 938C>CT | 8.30 | none | Not found |

| 35 | 3:10183719 | Substitution | T>TC | Heterozygous | 901T>TC | 9.10 |

Leucine/Proline | Not found |

| 36 | 3:10183764 | Substitution | A>AG | Heterozygous | 946A>AG | 12.50 |

Asparagine/serine | found |

| KDR gene |

| 1 | 4:55971029 | Substitution | C>CG | Heterozygous | 21234C>CG | 28.00 |

Proline/Alanine | Not found |

| 2 | 4:55970820 | Substitution | C>CT | Heterozygous | 21443C>CT | 8.30 | None | Not found |

| 3 | 4:55970985 | Substitution | G>GT | Heterozygous | 21278G>GT | 16.70 |

Lysin/Asparagine | Not found |

| 4 | 4:55970981 | Substitution | T>TC | Heterozygous | 21282T>TC | 12.50 |

Leucine/Proline | Not found |

| 5 | 4:55970980 | Substitution | T>TC | Heterozygous | 21283T>TC | 12.50 |

Leucine/Proline | Not found |

| 6 | 4:55970991 | Substitution | T>TC | Heterozygous | 21272T>TC | 16.70 | None | Not found |

| 7 | 4:55970969 | Substitution | T>TG | Heterozygous | 21294T>TG | 20 |

Tryptophane/Glycine | Not found |

| 8 | 4:55970819 | Substitution | A>AC | Heterozygous | 21444A>AC | 8.30 |

Threonine/Proline | Not found |

| 9 | 4:55971034 | Substitution | C>CT | Heterozygous | 21229C>CT | 25.30 |

Proline/Leucine | Not found |

| 10 | 4:55971000 | Substitution | C>CT | Heterozygous | 21263C>CT | 25.10 | None | Not found |

| 11 | 4:55970978 | Substitution | G>GC | Heterozygous | 21285G>GC | 12.50 | Aspartic

acid/Histidine | Not found |

| 12 | 4:55970970 | Substitution | T>TC | Heterozygous | 21293T>TC | 10.00 | None | Not found |

| 13 | 4:55970996 | Substitution | C>CG | Heterozygous | 21267C>CG | 25.00 | Proline/Aspartic

acid | Not found |

| 14 | 4:55970995 | Substitution | C>CA | Heterozygous | 21268C>CA | 25.00 | Proline/Aspartic

acid | Not found |

| 15 | 4:55970892 | Substitution | G>GA | Heterozygous | 21371G>GA | 7.10 | None | Not found |

| 16 | 4:55970925 | Substitution | T>TG | Heterozygous | 21338T>TG | 7.10 | Aspartic

acid/Histidine | Not found |

Regarding to KDR gene, 16 heterozygous substitution

variant mutations (C>CG, C>CT, G>GT, T>TC, A>AC,

G>GC, C>CA, G>GA) were recorded in exon 13; all of them

were not recorded previously in external databases. A total of 11

of these mutations are associated with changes in the sequence of

amino acids. Furthermore, the heterozygous variant (21234C>CG)

constitutes the largest percentage (28%) among other variants

(Table II).

Database mutations and gene

interactions

The GnomAD tool was used to retrieve the entire

recorded mutations of VHL and KDR genes in all types of cancer. VHL

had 386 mutations, while KDR had 1,595 mutations as presented in

Table SI.

Additional analysis of retrieved VHL and KDR gene

mutations in RCC was performed using Metagene (all genome-wide

studies in ICGC) and COSMIC databases as demonstrated in Tables SII and SIII. The number of mutations in VHL was

125 and 1,569 in the Metagene and COSMIC databases, respectively;

however, the number of mutations of the KDR gene was 229 and 27 in

the same two databases, respectively. In the Mutagen database the

most common type of mutation in the VHL gene of patients with RCC

was missense mutation followed by nonsense mutation. Out of 125

mutations, 66 were passengers followed by 34 drivers and 25

potential driver mutations. Regarding the KDR gene, the most common

type of mutation was missense followed by silent mutation, and

their status in cancer participation was mostly passenger (n=179)

followed by potential driver (n=34) and driver (n=16) mutations. In

the COSMIC database, the frameshift deletion (n=530) was the most

common type of mutation of VHL in patients with ccRCC followed by

missense-substitution (n=339), frameshift insertion (n=219) and

nonsense substitution (n=62). However, missense substitutions

(n=20) were common types of mutations of the KDR gene in patients

with ccRCC followed by frameshift deletions (n=3), nonsense

substitution (n=2) and substitution-coding silent (n=2).

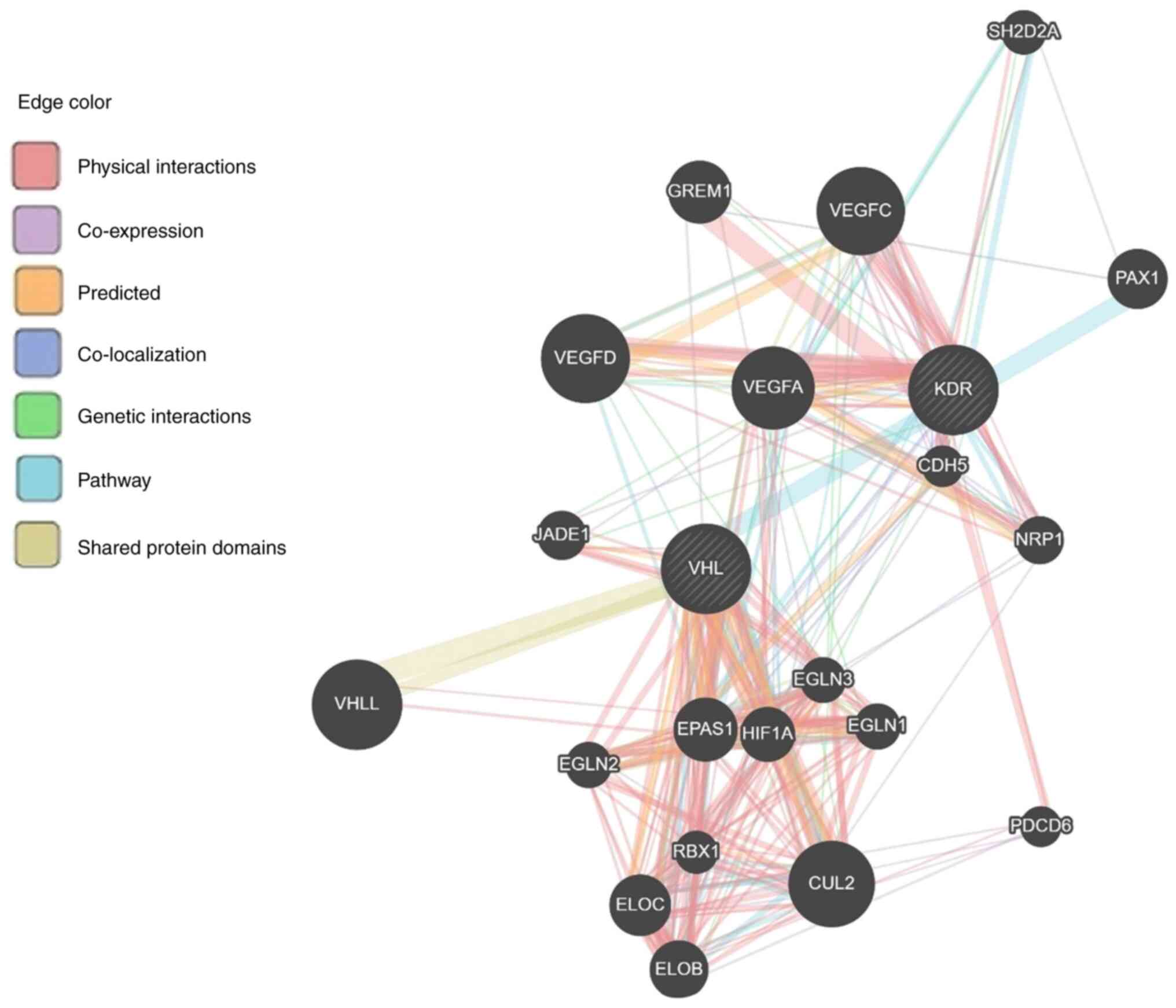

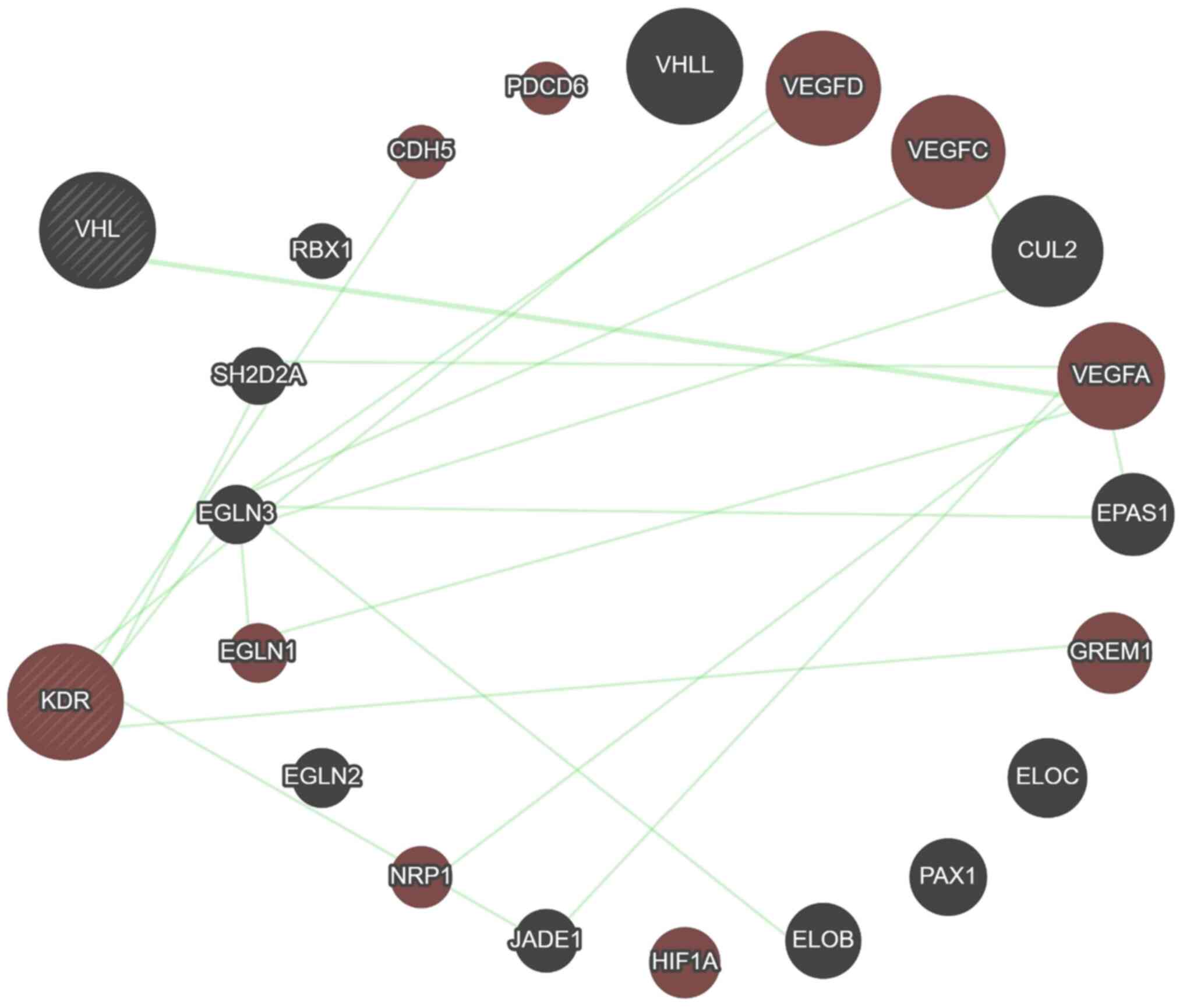

Moreover, data from the GeneMANIA predicting tool

revealed that 13 genes (RBX1, VHLL, CUL2, VEGFA, EPAS1, ELOC, PAX1,

ELOB, HIF1, JADE1, EGLN1, EGLN2 and EGLN3) and 12 genes (CDH5,

PDCD6, VEGFA, VEGFC, VEGFD, EPAS1, GREM1, HIF1, JADE1, NRP1, EGLN3

and SH2D2A) are associated with VHL and KDR genes, respectively,

mainly through physical interaction then co-expression, prediction,

colocalization, genetic interaction, pathway and minimum level by

sharing protein domain (Fig. 5 and

Table SIV). A total of five genes

(VEGFA, EPAS1, HIF1, JADE1 and EGLN3) are shared between VHL and

KDR genes, and this is considered a close relation between these

two genes. Furthermore, the KDR gene showed genetic interaction

with most of the genes having a role in angiogenesis (Fig. 6).

Discussion

In the present study, the sunitinib IC50

after 24 and 48 h was ~9x10-6 M, whereas after 72 h it

dropped to 5.26x10-6M. These results are very similar to

previous results demonstrating the cytotoxicity of sunitinib

against RCC cell lines. Sato et al (34) identified that the IC50

value of sunitinib against 786-O cells (3,000/well) was 5 µM after

a 48-h incubation. This disparity in the results might be

attributed to the initial cell count used in the experiment as the

current study involved plating 4,000 cells in each well of a

96-well plate, which could have affected the observed

IC50 value due to variations in cell density. Another

study reported that sunitinib IC50 was 3.99 µM against

Caki-1 cells after 48 h (35). In

this case, the discrepancy with the present results might be

attributed to the differences in the cell line.

In the current study, ccRCC 786-O cells were exposed

for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h to several concentrations of BAY-876. The

results demonstrated that BAY-876 can reduce 786-O cells in a

dose-dependent manner and the IC50 was

53.56x10-6 M. As RCC specimens demonstrated a remarkably

significant rise in the expression levels of GLUT1 compared with

the corresponding normal kidney tissue (36,37),

the present finding proves that reducing cell glucose intake by

inhibiting GLUT1 through BAY-876 treatment, could represent a new

strategy to suppress the growth of ccRCC. Moreover, the present

result is consistent with a recent study (38) showing that BAY-876 has an

inhibitory effect against bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA) cell

lines and tumor inhibition effect in xenograft models. It was

proposed that CLUTI inhibition through BAY-876 could be an

effective approach to inhibiting the growth of BLCA tumors.

Furthermore, another study (17)

revealed that BAY-876 is a strong blocker of GLUT1 activity,

mechanisms of glycolysis and ovarian cancer cell growth in ovarian

cancer cell lines, as well as cell line-derived xerographs and

ovarian cancer patient-derived xenografts.

The present results identified that the combination

of BAY-876 and sunitinib has a significant cytotoxic effect on

786-O cells at shorter incubation times (after 24 and 48 h)

compared with each drug alone, which had no cybotactic effect at

these intervals. This combination may eliminate the cell by

reducing the sugar intake by blocking GLUT1 transporters as well as

VEGF, PDGF and c-Kit receptors (39). The multi-shunt elimination of 786-O

cells during drug combination exposure may be attributable to a

reduction in the duration of cell death when compared with each

drug administered separately. This could be a promising advancement

in the treatment of RCC.

RCC presents a contradictory aspect of the action of

endogenous H2S. Numerous studies demonstrated an

increase in H2S levels or H2S-producing

enzymes in RCC cell lines, xenograft models and ccRCC tissues.

These findings suggested a correlation between H2S and

RCC growth and progression (40,41).

On the contrary, another study argued that the expression of

H2S-producing enzymes in ccRCC was reduced (42). The findings of the present study

indicated that the use of NaSH alone resulted in a significant

increase in cell death compared with the cells that were not

treated. This finding aligns with the results of a previous study

which demonstrated that NaSH has a significant impact on reducing

cell viability in three different breast cancer cell lines (MCF-10,

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-23) (43). The

aforementioned study also demonstrated that exogenous

H2S can suppress the progression of RCC by inhibiting

the P13K/AKT pathway as well as by inducing apoptosis.

The cytotoxic activity of both sunitinib and BAY-876

increased when combined with NaSH. Overall, the combination of NaSH

and BAY-876 could represent a novel approach to treating resistant

metastatic ccRCC. If they are used in treatment, they may reduce

the serious health impact and adverse reaction of sunitinib and

other TKIs.

The clinicopathological characteristics of the

patients in the present study revealed a slightly higher incidence

rate of ccRCC in male patients (56.6%) compared with female

patients (44.4%). However, a recent study demonstrated a

significantly higher incidence rate of ccRCC in male patients (80%)

compared with female patients (20%) (44). In addition, the TNM staging

revealed that the incidence rates for stages I, II and III were

76.66, 3.33 and 20%, respectively.

Inactivation of the gene encoding the tumor

suppressor VHL mutations is the most prevalent in ccRCC (45,46).

This present study revealed that the incidence of intragenic VHL

mutation was 43.7%, which is marginally lower than the percentage

observed in a study conducted in Japan, which was 51% (47). This may be because only exon 1 was

sequenced in the present research, whereas the entire gene was

sequenced in the study by Kondo et al (47). In addition, the present study

identified 36 missense SNP mutations in exon 1 of the VHL gene.

This funding is consistent with the findings of a recent study

which demonstrated that all mutations in VHL are missense mutations

in ccRCC (48), and with COSMIC

databases, which demonstrated that missense mutation is superior to

other types of mutations in RCC. Based on this number of point

mutations in VHL, mostly with an amino acid change (30 out of 36),

the present study suggested that mutations in this gene could be

the primary cause of ccRCC and confirmed that TKIs such as

sunitinib may be one of the best options for inhibiting the growth

of this type of kidney cancer, as they inhibit angiogenesis by

inhibiting the downstream pathways of VHL/HIF.

VEGFR-2 serves a crucial role as a primary mediator

in tumor angiogenesis and is regarded as a significant target for

therapeutic interventions to counteract angiogenesis. Several

anti-angiogenic medications, including ramucirumab, sunitinib,

axitinib and sorafenib, have been developed to target this pathway

(49). A previous study revealed

that the rs1870377 A>T genetic polymorphism of VEGFR-2 is

associated with the prognosis of gastric cancer (50). The present study demonstrated that

there were 16 heterozygous missense variants in exon 13 of KDR,

which is consistent with data from both the COSMIC and mutagen

databases. This may explain the function of KDR gene mutation in

the development of ccRCC and resistance to numerous anti-angiogenic

drugs. KDR mutation testing is crucial for guiding the choice of

therapy and improving patient outcomes.

Moreover, the present study found that BAY-876 and

NaSH could improve sunitinib's anticancer efficacy in ccRCC cell

lines, suggesting a novel treatment approach. It also found that

VHL mutation is the main cause of ccRCC development and KDR

mutation is necessary for angiogenesis. Testing these mutations

might help choose the right therapy and understand the illness

process. To the best of the authors' knowledge, the present study

is the first to identify a significant number of VHL and KDR gene

mutations in patients with ccRCC. By interpreting these gene

mutations and relating their detection with relevant

mutation-related datasets, the molecular mechanisms that initiate

and progress ccRCC were elucidated. The present investigation is

important in the context of RCC research and lays the groundwork

for future studies. However, additional research is needed to

confirm the current outcomes on other cell lines, also to determine

the cellular and physiological effects of these agents. Functional

studies could investigate the molecular effects of these mutations,

their effects on clinical outcomes in larger groups, their

predictive value for treatment response and genomic analysis to

identify more mutations and variations. Notably, the significance

of tracking response rate and cancer regression rate over time is

recognized as a crucial avenue for future research and it is

intended by the authors to contemplate integrating this data into

subsequent research endeavors or offering a more comprehensive

analysis in subsequent studies.

Supplementary Material

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR

product for tumor suppressor gene Von Hippel Lindau and kinase

insert domain receptor genes. (A) Represent amplification of exon I

of VHL gene. (B) Represent the amplification segment of axon 13 of

KRD gene. Lane 1: Ladder. Lane 2-16 demonstrate PCR products of

ccRCC patients. The bands for both VHL and KRD fragments for all

patients were located within the expected fragment size (VHL=260 bp

and KDR=290 bp).

Summary of mutations in the VHL and

KDR genes in all types of cancer retrieved from the gnomAD

database.

Summary of mutations in the VHL and

KDR genes in renal cell carcinoma retrieved from the Mutagene

database.

Summary of mutations in the VHL and

KDR genes in ccRCC retrieved from the COSMIC database.

The interaction between VHL ad KDR

gene and their related genes retrieved from GeneMania database

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Abbas Salihi from

Salahaddin University in Erbil, Salahaddin Universality Research

Center as well as the Histopathology department and laboratory

staff members at Nanakaly Hospital, Rizgary Hospital, and Par

Hospital in Erbil, Iraq, for providing samples.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

PSH conceived and designed the experiments,

performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures

and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article. KAM

conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments,

authored, or reviewed drafts of the article. PSH and KAM confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. Both authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved (approval no. 45/90)

by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Affiliated Salahaddin

University (Erbil, Iraq). Written informed consent forms were

obtained from the participants approving the use of their tissues

for investigation.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bahadoram S, Davoodi M, Hassanzadeh S,

Bahadoram M, Barahman M and Mafakher L: Renal cell carcinoma: An

overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. G Ital

Nefrol. 39:32–47. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:7–33.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Monjaras-Avila CU, Lorenzo-Leal AC,

Luque-Badillo AC, D'Costa N, Chavez-Muñoz C and Bach H: The tumor

immune microenvironment in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Int J

Mol Sci. 24(7946)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kase AM, George DJ and Ramalingam S: Clear

cell renal cell carcinoma: From biology to treatment. Cancers

(Basel). 15(665)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Padala SA and Barsouk A, Thandra KC,

Saginala K, Mohammed A, Vakiti A, Rawla P and Barsouk A:

Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. World J Oncol. 11:79–87.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Jonasch E, Walker CL and Rathmell WK:

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma ontogeny and mechanisms of

lethality. Nat Rev Nephrol. 17:245–261. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Nickerson ML, Jaeger E, Shi Y, Durocher

JA, Mahurkar S, Zaridze D, Matveev V, Janout V, Kollarova H, Bencko

V, et al: Improved identification of von Hippel-Lindau gene

alterations in clear cell renal tumors. Clin Cancer Res.

14:4726–4734. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Dizman N, Philip EJ and Pal SK: Genomic

profiling in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Nephrol. 16:435–451.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Williamson SR: Clear cell papillary renal

cell carcinoma: An update after 15 years. Pathology. 53:109–119.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sharma R, Kadife E, Myers M, Kannourakis

G, Prithviraj P and Ahmed N: Determinants of resistance to VEGF-TKI

and immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic renal cell

carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40(186)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hsieh JJ, Purdue MP, Signoretti S, Swanton

C, Albiges L, Schmidinger M, Heng DY, Larkin J and Ficarra V: Renal

cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 3(17009)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Makino T, Kadomoto S, Izumi K and Mizokami

A: Epidemiology and prevention of renal cell carcinoma. Cancers

(Basel). 14(4059)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Choi WSW, Boland J and Lin J:

Hypoxia-inducible factor-2α as a novel target in renal cell

carcinoma. J Kidney Cancer VHL. 8:1–7. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P,

Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik

C, Kim ST, et al: Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic

renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 356:115–124. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Jin J, Xie Y, Zhang JS, Wang JQ, Dai SJ,

He WF, Li SY, Ashby CR Jr, Chen ZS and He Q: Sunitinib resistance

in renal cell carcinoma: From molecular mechanisms to predictive

biomarkers. Drug Resist Updat. 67(100929)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Rini BI, Tamaskar I, Shaheen P, Salas R,

Garcia J, Wood L, Reddy S, Dreicer R and Bukowski RM:

Hypothyroidism in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma

treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 99:81–83.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ma Y, Wang W, Idowu MO, Oh U, Wang XY,

Temkin SM and Fang X: Ovarian cancer relies on glucose transporter

1 to fuel glycolysis and growth: Anti-tumor activity of BAY-876.

Cancers (Basel). 11(33)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Mantle D and Yang G: Hydrogen sulfide and

metal interaction: The pathophysiological implications. Mol Cell

Biochem. 477:2235–2248. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Zaorska E, Tomasova L, Koszelewski D,

Ostaszewski R and Ufnal M: hydrogen sulfide in pharmacotherapy,

beyond the hydrogen sulfide-donors. Biomolecules.

10(323)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Khattak S, Rauf MA, Khan NH, Zhang QQ,

Chen HJ, Muhammad P, Ansari MA, Alomary MN, Jahangir M, Zhang CY,

et al: Hydrogen sulfide biology and its role in cancer. Molecules.

27(3389)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Cao X, Ding L, Xie ZZ, Yang Y, Whiteman M,

Moore PK and Bian JS: A review of hydrogen sulfide synthesis,

metabolism, and measurement: Is modulation of hydrogen sulfide a

novel therapeutic for cancer? Antioxid Redox Signal. 31:1–38.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Powell CR, Dillon KM and Matson JB: A

review of hydrogen sulfide (H(2)S) donors: Chemistry and potential

therapeutic applications. Biochem Pharmacol. 149:110–123.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Chen G, Zhang Y and Wu X: 786-0 renal

cancer cell line-derived exosomes promote 786-0 cell migration and

invasion in vitro. Oncol Lett. 7:1576–1580. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Gu L, Sang Y, Nan X, Zheng Y, Liu F, Meng

L, Sang M and Shan B: circCYP24A1 facilitates esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma progression through binding PKM2 to regulate

NF-κB-induced CCL5 secretion. Mol Cancer. 21(217)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Warren AY and Harrison D: WHO/ISUP

classification, grading and pathological staging of renal cell

carcinoma: Standards and controversies. World J Urol. 36:1913–1926.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Elkassem AA, Allen BC, Sharbidre KG,

Rais-Bahrami S and Smith AD: Update on the role of imaging in

clinical staging and restaging of renal cell carcinoma based on the

AJCC 8th edition, from the AJR special series on cancer staging.

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 217:541–555. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Delahunt B, Eble JN, Samaratunga H,

Thunders M, Yaxley JW and Egevad L: Staging of renal cell

carcinoma: Current progress and potential advances. Pathology.

53:120–128. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Abid MN, Qadir FA and Salihi A:

Association between the serum concentrations and mutational status

of IL-8, IL-27 and VEGF and the expression levels of the hERG

potassium channel gene in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol

Lett. 22(665)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Alves MR, Carneiro FC, Lavorato-Rocha AM,

da Costa WH, da Cunha IW, de Cássio Zequi S, Guimaraes GC, Soares

FA, Carraro DM and Rocha RM: Mutational status of VHL gene and its

clinical importance in renal clear cell carcinoma. Virchows Arch.

465:321–330. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Housein Z, Kareem TS and Salihi A: In

vitro anticancer activity of hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide

alongside nickel nanoparticle and novel mutations in their genes in

CRC patients. Sci Rep. 11(2536)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Gudmundsson S, Singer-Berk M, Watts NA,

Phu W, Goodrich JK and Solomonson M: Genome Aggregation Database

Consortium. Rehm HL, MacArthur DG and O'Donnell-Luria A: Variant

interpretation using population databases: Lessons from gnomAD. Hum

Mutat. 43:1012–1030. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Sondka Z, Bamford S, Cole CG, Ward SA,

Dunham I and Forbes SA: The COSMIC cancer gene census: Describing

genetic dysfunction across all human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer.

18:696–705. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Franz M, Rodriguez H, Lopes C, Zuberi K,

Montojo J, Bader GD and Morris Q: GeneMANIA update 2018. Nucleic

Acids Res. 46:W60–W64. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Sato H, Siddig S, Uzu M, Suzuki S, Nomura

Y, Kashiba T, Gushimiyagi K, Sekine Y, Uehara T, Arano Y, et al:

Elacridar enhances the cytotoxic effects of sunitinib and prevents

multidrug resistance in renal carcinoma cells. Eur J Pharmacol.

746:258–266. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Amaro F, Pisoeiro C, Valente MJ, Bastos

ML, de Pinho PG, Carvalho M and Pinto J: Sunitinib versus pazopanib

dilemma in renal cell carcinoma: New Insights into the in vitro

metabolic impact, efficacy, and safety. Int J Mol Sci.

23(9898)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Singer K, Kastenberger M, Gottfried E,

Hammerschmied CG, Büttner M, Aigner M, Seliger B, Walter B,

Schlösser H, Hartmann A, et al: Warburg phenotype in renal cell

carcinoma: high expression of glucose-transporter 1 (GLUT-1)

correlates with low CD8(+) T-cell infiltration in the tumor. Int J

Cancer. 128:2085–2095. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Abdolahi M, Alam M, Ghaffarpasand A, Nouri

F, Badkoobeh A, Golkar M, Abassi K and Torbati P: Assessment of the

expression of GLUT1 in renal cell carcinoma and its various

subtypes. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 10:2581–2585. 2022.

|

|

38

|

Wang X, He H, Rui W, Zhang N, Zhu Y and

Xie X: TRIM38 triggers the uniquitination and degradation of

glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) to restrict tumor progression in

bladder cancer. J Transl Med. 19(508)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Kollmannsberger C, Soulieres D, Wong R,

Scalera A, Gaspo R and Bjarnason G: Sunitinib therapy for

metastatic renal cell carcinoma: recommendations for management of

side effects. Can Urol Assoc J. 1:S41–S54. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Sonke E, Verrydt M, Postenka CO, Pardhan

S, Willie CJ, Mazzola CR, Hammers MD, Pluth MD, Lobb I, Power N, et

al: Inhibition of endogenous hydrogen sulfide production in

clear-cell renal cell carcinoma cell lines and xenografts restricts

their growth, survival and angiogenic potential. Nitric Oxide.

49:26–39. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Shackelford RE, Abdulsattar J, Wei EX,

Cotelingam J, Coppola D and Herrera GA: Increased nicotinamide

phosphoribosyltransferase and cystathionine-β-synthase in renal

oncocytomas, renal urothelial carcinoma, and renal clear cell

carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 37:3423–3427. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Breza J Jr, Soltysova A, Hudecova S,

Penesova A, Szadvari I, Babula P, Chovancova B, Lencesova L, Pos O,

Breza J, et al: Endogenous H(2)S producing enzymes are involved in

apoptosis induction in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer.

18(591)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Dong Q, Yang B, Han JG, Zhang MM, Liu W,

Zhang X, Yu HL, Liu ZG, Zhang SH, Li T, et al: A novel hydrogen

sulfide-releasing donor, HA-ADT, suppresses the growth of human

breast cancer cells through inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and

Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathways. Cancer Lett. 455:60–72.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Sekar H, Krishnamoorthy S, Kumaresan N,

Chandrasekaran D, Ramaswamy P, Sundaram S and Raj N:

Clinicopathological comparison of VHL expression as a prognostic

tumor marker in renal cell carcinoma: A single center experience.

Niger J Clin Pract. 24:614–620. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Audenet F, Yates DR, Cancel-Tassin G,

Cussenot O and Rouprêt M: Genetic pathways involved in

carcinogenesis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Genomics towards

personalized medicine. BJU Int. 109:1864–1870. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW,

Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER and

Ratcliffe PJ: The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets

hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature.

399:271–275. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Kondo K, Yao M, Yoshida M, Kishida T,

Shuin T, Miura T, Moriyama M, Kobayashi K, Sakai N, Kaneko S, et

al: Comprehensive mutational analysis of the VHL gene in sporadic

renal cell carcinoma: Relationship to clinicopathological

parameters. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 34:58–68. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Lin PH, Huang CY, Yu KJ, Kan HC, Liu CY,

Chuang CK, Lu YC, Chang YH, Shao IH and Pang ST: Genomic

characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma using targeted

gene sequencing. Oncol Lett. 21(169)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Shah AA, Kamal MA and Akhtar S: Tumor

angiogenesis and VEGFR-2: Mechanism, pathways and current

biological therapeutic interventions. Curr Drug Metab. 22:50–59.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Zhu X, Wang Y, Xue W, Wang R, Wang L, Zhu

ML and Zheng L: The VEGFR-2 protein and the VEGFR-2 rs1870377

A>T genetic polymorphism are prognostic factors for gastric

cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 20:497–504. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|